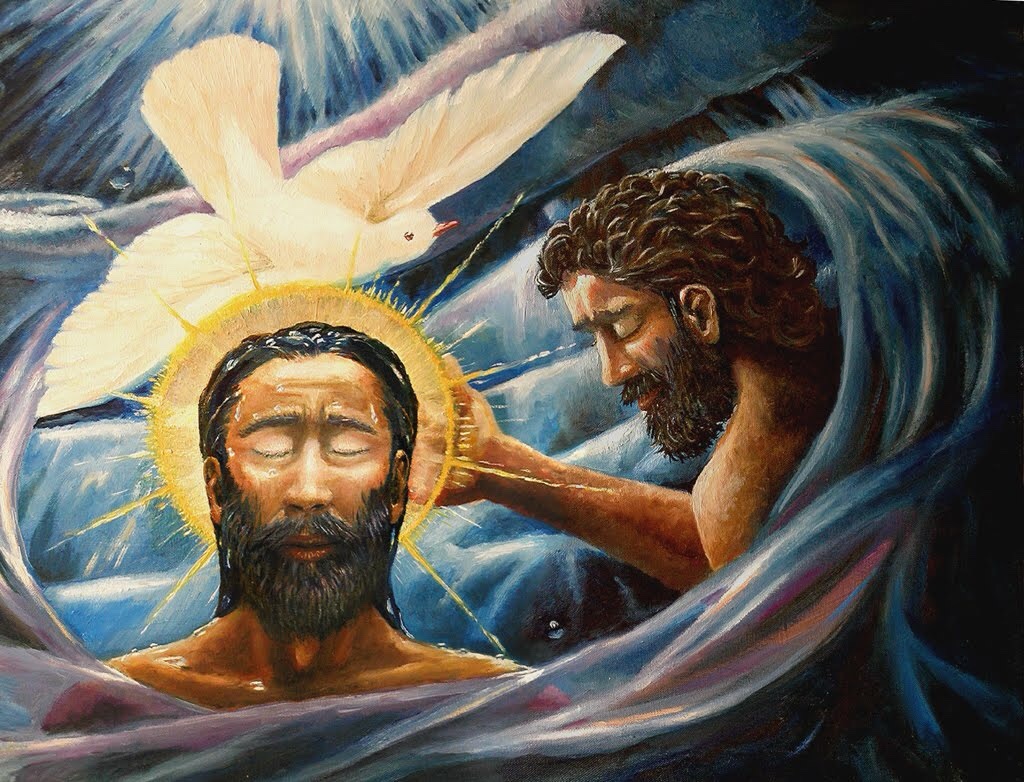

The lectionary for this Sunday suggests, as a companion piece to Luke’s account of The Baptism of Jesus, when the Spirit descends on Jesus (Luke 3:1–22), a short section from Luke’s second volume telling of further baptisms and gifting of the Spirit to new believers in Samaria (Acts 8:14–17).

In chapter nine of Acts, Saul is “converted” by a vision seen on the road to Damascus, is struck blind, then has his sight restored, is “filled with the Spirit”, and receives his commission to preach to the Gentiles (Acts 9:1–19). This would prove to be a significant turning point in the story Luke tells, which soon morphs into an account of the travels undertaken by Saul, who adopts the name Paul, and his various companions, as they preach to Jews and Gentiles in many different towns and cities.

In chapter ten of Acts, Peter is likewise “converted” by a vision seen on a rooftop in Joppa, travels to Caesarea, preaches to the household of Cornelius, and sees that “the gift of the Holy Spirit had been poured out even on the Gentiles, for they heard them speaking in tongues and extolling God” (Acts 10:45–46). This was a second crucial turning point, for it enabled Peter, at a later gathering of leaders in Jerusalem, to affirm that “God made a choice among you, that I should be the one through whom the Gentiles would hear the message of the good news and become believers” (15:7), and then that God “testified to them [the Gentiles] by giving them the Holy Spirit, just as he did to us; and in cleansing their hearts by faith he has made no distinction between them and us” (15:8–9).

So it was that, in Luke’s telling of the story, these two key figures each pressed the case that “God has given even to the Gentiles the repentance that leads to life” (11:18, my emphasis added). The third dominant figure in the early days of this movement, James the brother of Jesus, joined his voice to theirs at the council in Jerusalem, giving the final decision of the council that “we should not trouble those Gentiles who are turning to God” (15:19)—they are to be fully accepted within the fellowship of the growing movement. The council sent four members to Antioch with the declaration that “it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us” to convey this good news (15:28).

Before all of this, in chapter eight of Acts, there is another story involving the Spirit. Philip travels to Samaria, preaches to crowds of people, encounters a man named Simon, a local magician, and rejoices when Simon, as well as many others, accept his message and are baptised (8:4–13). However, there is a problem; as Luke comments in a narrator’s aside, “as yet the Spirit had not come upon any of them; they had only been baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus” (8:16). So the two lead apostles, Peter and John, are despatched to Samaria to deal with the situation.

This is the story that the lectionary chooses to place alongside the account of the baptism of Jesus for this coming Sunday, the first Sunday in the season of Epiphany. This day is designated each year as the time to recall the baptism of Jesus. So this passage from Acts seems a suitable companion reading.

In particular, it invites us to explore a little further the place of the Spirit in the early decades of the movement initiated by Jesus. And although the selected passage stops short at verse 17, the narrative continues on, describing the disruption which came from the preaching of Philip and the visit of Peter and John. It was a disruption that brought transformation to Simon the magician (see his prayer at 8:24) and to the Samaritans in other villages where the good news was proclaimed (8:25).

Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574),

“Apostles Peter and John Blessing the People of Samaria”

In this short narrative of the apostolic visit to Samaria, the Samaritans who had already “received the word of God” from Philip (8:14) were enabled to “receive the holy spirit” through the laying on of hands by the apostles who had been sent to the region (8:15-18). Although the gift of the spirit (8:17) had been separated from baptism (8:12), as it would later be in a narrative concerning events in Ephesus (19:1-7), Luke does not intend this pattern to be read as prescriptive for all situations, as other accounts of baptisms indicate (2:38-41; 8:38; 10:44-48; 19:1-7).

Baptism had been proclaimed as necessary by Peter, on the day of Pentecost (2:38); this appears to link baptism closely with the gift of the Spirit (2;1-4, 17-21). However, there is no formulaic pattern or process to be followed each time a baptism takes place. The various narratives are somewhat ad hoc. The spirit guides Philip in the encounter with a eunuch returning from Jerusalem to Ethiopia (8:29, 39)—but the spirit appears to have no direct contact with the Ethiopian himself.

Baptism is accompanied by the laying-on of hands here in Samaria (8:15-16) and later in Ephesus (19:6), but not with the Ethiopian. The laying-on of hands results in the holy spirit coming upon those in Ephesus (19:6), a link similar to that made in Samaria (8:15-17, 19) and Antioch (13:3-4). The gift of the spirit leads to speaking in tongues in Ephesus (19:7), as in Jerusalem (2:4) and Caesarea (10:45-46), but not for the Ethiopian.

In Acts, baptism may come both prior to (2:38-42; 8:14-17) and after (10:44-48; 11:15-17) the gift of the spirit; further, the gift of the spirit is not necessarily linked with baptism (for instance, at 2:1-4 and 4:31). Confused? We need to remember that Luke is telling stories, recounting happenings that he has been told about or that he has read in earlier sources. He is not setting out precise liturgical or doctrinal instruction. So, whilst the time sequence of the elements of spirit—laying on hands—water—baptism is found in different patterns, the collation of similar elements across all these stories implies a consistent cluster of elements. Read this way, there is strong continuity with events in Jerusalem, Samaria, Caesarea, and Ephesus. The baptisms in Samaria fit, by inference, within that sequence.

Whenever Christians think about the Spirit—and specifically about the dynamic force that is displayed by the Holy Spirit—our attention goes most immediately to the story of the Day of Pentecost in Acts 2. That’s when the coming of the Spirit was experienced as “a sound like the rush of a violent wind [which] filled the entire house where they were sitting”, followed by “tongues, as of fire … resting on each of them” (vv.2–3).

In the chaos that resulted—“all of them … began to speak in other languages”—the crowd that heard them were bewildered, amazed, astonished, and thought that they were drunk! That’s a disruptive event initiated and impelled by the Spirit right there. The story of Pentecost is a story about God intervening, overturning, and reshaping the people of God. The Spirit certainly was active at Pentecost. It was a transformative moment.

As Luke tells the story of Pentecost, he is deliberately linking his second volume, not only to the activity of the Spirit in Hebrew Scriptures, but also to the way the Spirit overshadowed Mary (Luke 1:35), nurtured John, son of Zechariah and Elizabeth (1:80), descended upon Jesus at his baptism (3:22), led Jesus out into the Judean wilderness (4:1) and then back into Galilee (Luke 4:14) to sustain the activities and preaching of Jesus (4:18; 10:21).

Luke, of course, had received the account of the active role of the spirit in the baptism and testing of Jesus (Mark 1:10, 12) and developed it, just as Matthew had done likewise, introducing the saying of Jesus, “if it is by the Spirit of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come to you” (Matt 12:28).

Certainly, the activities of Jesus can only be thought of as both disruptive—framed by the breach of the heavens at his baptism, the tearing of the temple curtain at his death—and as transformative—signalled by the transfiguration on the mountain top, as well as the change in the disciples effected by their time with Jesus.

Some interpreters have noted that the book of Acts is less about “the acts (deeds) of the apostles” than it is about “the acts of the Holy Spirit”.

The author himself described the two-volume work (Luke’s Gospel and Acts) as an orderly account of the things that have come to fulfilment amongst us. The work highlights how the Holy Spirit plays a central, active role in what is being reported—how the Spirit might be seen to bring, first disruption, and then transformation, in the movement that Jesus inspired.

The events reported in Acts are generated from the dramatic intervention of the Spirit into the early community formed by the followers of Jesus after his ascension. The story of that intervention reports that Jews came from around the eastern Mediterranean are gathered in Jerusalem for the annual festival (Acts 2:1–13), when the Spirit comes upon them. Each bursts out, “speaking about God’s deeds of power” (2:11). The joy and excitement is tangible even as we hear the story at two millennia’s distance.

Unthinkingly, the wider group of pilgrims hear the cacophony of Spirit-inspired voices, and assume that this is a sign of drunkenness (2:13, 15). Actually, as Luke has made clear, the tongues being heard are not the unintelligible gibberish evident in Corinth, but known languages from the various places of origin of those speaking. And the disruptive element is not from the tongues spoken, but from the actions undertaken by believers in the days, months, and years ahead—as the narrative of Acts conveys. It’s a dramatic story with clear theological guidelines.

Another dramatic story of the coming of the Spirit is told at a later point in Acts—after Peter sees a vision in which God declares “all food is clean”, and he is summoned to the home of the Gentile centurion, Cornelius, in Caesarea (10:1–33). As Peter preaches to the Gentiles, the Spirit falls on them, “just as it had upon us [Jews] at the beginning (11:15). This event is specifically portrayed as a complementary event alongside the falling of the Spirit on Jews on the Day of Pentecost (2:1–4). It is a further disruptive action that the Spirit impels. And its consequences—full acceptance of the place of Gentiles in this movement—were fully transformative.

The activity of the Spirit is noted at various places in this sequence of events. The Spirit guides Peter to meet the men sent by Cornelius and travel with them to Caesarea (10:19; 11:12). In reporting to the church in Jerusalem about the arrival of messengers from Cornelius (11:11–12), Peter notes simply that “the spirit said to me to go with them without criticism” (11:12; cf. 10:19–20).

In this report to the Jerusalem church, Peter is short on factual reporting, as it were; he simply states that the spirit fell on them (11:15). His omission of many details (character traits, travel details, conversation and personnel; even, surprisingly, the name of Cornelius) places the focus on the role of the spirit. Once again, what the Spirit impels from this vision, visit, and sermon, is highly disruptive and thoroughly transformative for the early communities of faith.

Jews had been used to eating separately from Gentiles and selectively in terms of food, in accordance with the prescriptions of Leviticus. Now, they are now invited—indeed, commanded—to share at table with Gentiles and to put aside the traditional dietary demarcations.

This is disruptive: just imagine being commanded by God to become vegan and eat meals with the family of your worst nightmares, for instance! And it is transformative: from this sequence there emerge inclusive communities of Jews and Gentiles across the Mediterranean basin, sharing at table and in all manner of ways. That becomes the way of the church.

The importance of the Spirit in Luke’s account of the early movement cannot be underestimated. The significance for the church today of the Spirit’s disruptive, empowering, transformative presence at Pentecost is likewise high. And that transformative activity continues on throughout Acts.

After Peter’s sermon in Caesarea and the gifting of the Spirit to the Gentiles (Acts 10—11), the Spirit guides Barnabas and Paul to Seleucia and onwards (13:2) and then later guides Paul away from Asia Minor, towards Macedonia (16:6–7). This latter move marks a critical stage in the story that Luke tells.

At this key moment of decision in Troas, three injunctions are given; each one is from a divine source. The first of these, an instruction not to speak in the southern region of Asia, comes from the Holy Spirit (16:6). The second direction, a prohibition against any attempt to head north and enter Bithynia, comes from the same spirit, here described as “the spirit of Jesus” (16:7). The third divine interjection takes place at Troas, where a vision is seen in the night with a petition to “come across into Macedonia” (16:9).

The new spirit-inspired direction of travel is disorienting; a serious disagreement between Paul and Barnabas had just occurred (15:39). But this disruption provides the springboard for Paul and Silas to undertake a new mission in Philippi, Thessalonica, and Beroea (16:11—17:15), before visiting the centre of Greek philosophy and politics, Athens (17:16–34), and then Corinth, where Paul stayed eighteen months (18:1–17). Indeed, all that takes place, as Paul travels relentlessly with various companions across many places (13:4—21:17), is driven by the Spirit (13:2, 4), a constantly disruptive and transformative presence.

Much later, Paul’s final visit to Jerusalem and his subsequent arrest takes place under the guidance of the Spirit (20:22-23; 21:11). That event had hugely disruptive consequences for Paul, of course, as he is arrested and spends the rest of his life as a prisoner under Roman guard.

The story of the early years of the movement initiated by Jesus, then, is of multiple events inspired and propelled by the Spirit over these years—intrusive, disruptive, yet transformative events. The Spirit who guides all of this brings both disruption and transformation. We need, today, to be open to the same disruption and transformation.