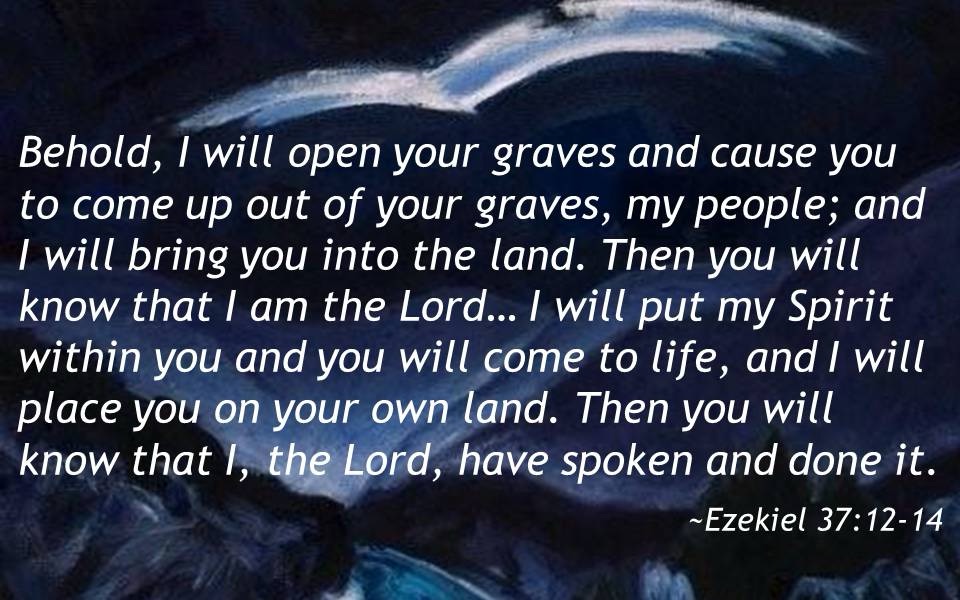

In the alternate reading that the Revised Common Lectionary proposes for the festival of Pentecost, this coming Sunday, we find a section from the exilic prophet Ezekiel (Ezek 37:1–14). This is the famous prophecy covering the dead bones, to which the Lord (through Ezekiel) declares, “I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live. I will lay sinews on you, and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live; and you shall know that I am the Lord” (Ezek 37:5–6).

However, this passage also contains words which were filled with hope for the exiled people—but which, in the light of current events in the Middle East, and especially since the eruption of conflict on 7 October last year, are fraught with difficulties. God instructs Ezekiel, “prophesy, and say to them, Thus says the Lord God: I am going to open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. … I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you on your own soil; then you shall know that I, the Lord, have spoken” (Ezek 37:12,14).

However, this passage also contains words which were filled with hope for the exiled people—but which, in the light of current events in the Middle East, and especially since the eruption of conflict on 7 October last year, are fraught with difficulties. God instructs Ezekiel, “prophesy, and say to them, Thus says the Lord God: I am going to open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. … I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you on your own soil; then you shall know that I, the Lord, have spoken” (Ezek 37:12,14).

These words are fraught because of the long history of conflict relating to “the land of Israel”—the land to which the exiles would return under the decree of Cyrus of Persia; the land which today is the focus of such controversy and conflicted claims.

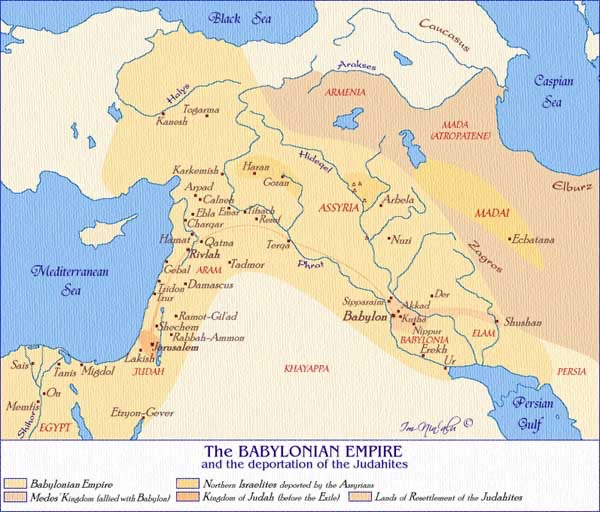

The land marked out for Israel was based on the historical reality that in ancient times Israelites/Jews had lived on that land for centuries until the scattering of all Jews under Roman rule first and second centuries of the Common Era. But since then, Arabs of various origins had held control of the land (see below), and those living there came to be known as Palestinians.

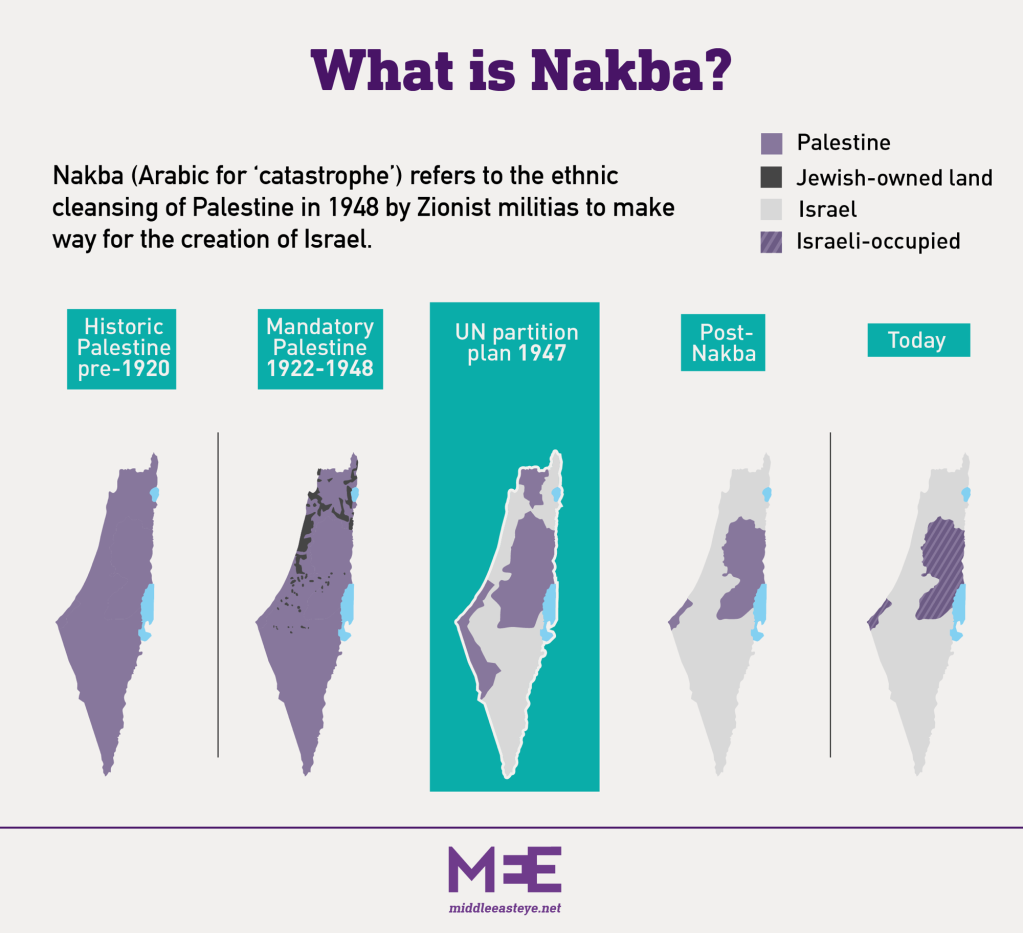

In the early 20th century, the place where Arabs who identified as Palestinians were living was decreed to be the British Mandate of Palestine (1920–1948). The ancient conflicts, it was hoped, would be well in the past. A place for Palestinians in the modern world was, it was thought, now settled. But this was not to be, as we well know today.

In part in response to the horrors of the Shoah, exposed by the ending of World War Two, the modern state of Israel was created in 1948. This was a hugely important, completely justified step to take, give the atrocities of genocide that had been inflicted on Jews in Europe by the Nazi regime of Germany.

The new nation of Israel took 78% of the area which had been provided for Palestinians in the British Mandate. That this was now Jewish territory was a blessing for Jews, but it was a huge and continuing irritant to Palestinian sensibilities, which is why the period from 1948 onwards is known as the Nakba, the Palestinian Catastrophe. A significant number of Palestinians fled the area declared as Israel, as (in one estimate) over 500 Palestinian villages were repopulated by Jews, becoming refugees with no national identity. That was indeed a catastrophe for those inhabitants.

The contested regions of the Gaza Strip (along the east coastline of the Mediterranean Sea) and the West Bank (land immediately to the west of the River Jordan) became known as the Palestinian Territories. They have been disputed territories ever since they were occupied by Israel, two decades later, in the Six-Day War of 1967. In the decades since then, continuing and increasingly aggressive expansion of Israeli settlements into areas where Palestinians were living has greatly exacerbated the situation.

And so those who were dispossessed—and offered the hope of return to “their land”—become the dispossessors of others, to whom that same land was also “their land”; and so the tragic cycle continues.

The biblical texts which claim that God gave land to a chosen people so long ago are not verbatim accounts of “what God said” long ago, nor are they historical reports of actual events. They were written by priests returning from Exile, trying to recapture the period when Israel had some autonomy, because of the strength of its army under various tribal leaders (presented as “kings”). The texts form aetiological tales—that is, they are written as stories at a point in time, purporting to be ancient records, laying the foundation for a claim such as “this is our land, God gave it to us”.

That same land, promised to Abraham, claimed by Moses, is in contention today. It has had a chequered history. The ancient land of Cana an eventually became the land of Israel, then (along with Judaea) part of the Roman province of Syria Palaestina (132–390), and then of the Diocese of the East in the Roman Empire (to 536). What followed the fall of the Roman Empire was a millennium and a half of Muslim rule of this land, first as a part of Bilad al-Sham, the Greater Syria region, under various Caliphates.

The region continued to be part of various organisational configurations under successive Muslim rule, on into the Ottoman Caliphate (from 1517) and then into the modern era, as already noted. (I am not an expert, by any means, of this ancient and medieval history; for this summary, I am dependent on what I read in what I consider to be reputable sources.)

An exaggerated, idealised view of the extent of the land claimed by modern-day Israelis is evident in so many ways in the portrayal of Solomon, who was seen to be filled with “wisdom and knowledge”, and granted “riches, possessions, and honour, such as none of the kings had who were before you, and none after you shall have the like” (2 Chron 1:7–12, especially verses 10 and 12). The biblical figure of Solomon is an exaggerated caricature, a description of an idealised ruler whose existence is actually still a matter of debate amongst ancient historians.

It is also worth noting that the large reach of land that Solomon ruled over, even more extensive than the oft-cited phrase “from Dan to Beersheba” (Judg 20:1; 1 Sam 3:20; 2 Sam 3:10; 17:11; 24:2, 15; 1 Ki 4:25; 1 Chron 21:2; 2 Chron 30:5), did not continue past his death. The hagiographical exaggeration of territory under Solomon is not noted in the period after his death. The narrative books that recount the stories of the kingdoms of Israel, in the north, and Judah, in the south, in the centuries after Solomon, indicate that the scope of those kingdoms was more constrained.

*****

In the light of this, we need to take care when we come across texts in the Hebrew Scriptures which dogmatically and definitively declare that this land belongs to the people of Israel. Indeed, even scripture itself tells the story of the invading colonisers who claimed this land for their own (in the book of Joshua).

So I don’t think it is responsible, today, to lay claim to the whole, extended territory of the land, from the biblical passages noted, as the scope for the modern state of Israel which was created in 1948. There is no justification for the continued aggressive expansion of Israeli settlements in Palestinian areas. So I have sympathy for Palestinians who have lived on the land for thousands of years prior to 1948, as they understand this to be their ancestral land. It has been a continuing Nakba, a catastrophe, for Palestinians over these decades.

I also have sympathy for Jews, both those living in the land of Israel today, as well as those living in diaspora, for whom the land of Israel has a powerful symbolic significance—especially since the Shoah of 1933—1945 and the terrible genocide perpetrated by the Nazis against Jews in so many countries during that period. Granting them land in the area where their ancestors long ago had lived, a homeland that gives them security in the modern world, is important and necessary.

That said, I don’t agree that Palestinians should take matters into their own hands to seek vengeance against people in Israel in the way that they have done, once again, in recent months. In the same manner, nor do I think that the Israeli forces should respond in the aggressive and violent manner that they have done, once again, in recent times, with deaths of women and children, and aid workers, noted on the news with dreadful persistence. Too many people—innocent people—are dying and being injured, making any possible progress towards peace with justice even more difficult each day.

We need to seek once more the peace of these peoples. And we need to find that peace on the basis of justice. Neither terrorist attacks nor military crackdowns will achieve this. They will simply exacerbate a dangerous situation.

How do we deal, today, with the promises of God made long ago? “I will bring you back to the land of Israel. … I will place you on your own soil” (Ezek 37:12,14). We need to tread with care. Perhaps some other texts from both Jewish scripture Christian scripture provide guidance.

“Depart from evil, and do good; seek peace, and pursue it.” (Psalm 34:14). “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.” (Matt 5:9). “Justice, and only justice, you shall pursue, so that you may live and occupy the land that the Lord your God is giving you.” (Deut 16:20). “… the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faith. It is these you ought to have practiced …” (Mat 23:23). May these be the principles that guide the leaders of the warring groups in Israel and Palestine today.