The Gospel reading for this coming Sunday provides the name by which this Sunday is often known in church tradition: it is Thomas Sunday. (The reading is John 20:19-31.)

We all know about Thomas: he had to have proof … had to see with his own eyes … had to touch to know it was real … did not have faith without tangible proof. Thomas often gets a bad rap: oh he of little faith! … why did he not believe straight away, like the others who followed Jesus? … why was he in the thrall of doubt at precisely the time that faith was called for?

Thomas wants to pin the matter down, to have the evidence produced, to know without question what has taken place. We remember him from this story, as the doubting sceptic.

Let us reflect a little on this: Thomas was not alone. All the other early witnesses, followers, and writers, in the movement of people clustered around Jesus, had the same need to pin the matter down. There were many sceptics in this movement. They needed some form of proof. They looked for evidence. They sought signs that would validate the new way that Jesus was in their midst.

The endings of the Gospels testify to this. The earliest Gospel ended with an open narrative, hanging on those words: the tomb is empty — he is not here! (See https://johntsquires.wordpress.com/2019/04/21/the-tomb-is-empty-he-is-not-here-he-is-risen/)

Subsequent compilers of the narrative about Jesus could not live with the uncertainty of an open-ended story, with an absent Jesus who would appear only in a distant, remote, unimportant location (Galilee). No; they had to have him come to the women, the travellers, even the inner core of disciples, in or near to Jerusalem. Indeed, Luke explicitly reports that the risen Jesus provided them with “many convincing proofs” after his resurrection (Acts 1:3).

Thomas, of course, is the disciple whom we most closely associate with doubt, not with faith, derived from this very report of his encounter with the risen Jesus. “Unless I see, I will not believe”, the sceptic Thomas says, in John 20. “Unless I can put my finger in the mark in the side of my master, I will not believe that he has risen”, declares Thomas.

And in the modern scientific era, where we operate by testing, questioning, doubting, and seeking to prove hypotheses, this kind of approach has a certain attractiveness. For some Christians in the present time, in the period of probing scientific hypotheses and seeking historical certainties, Thomas has become a kind of patron saint—a saint of doubting, questioning, and proving. “Unless I see, I will not believe” is the mantra of such a saint.

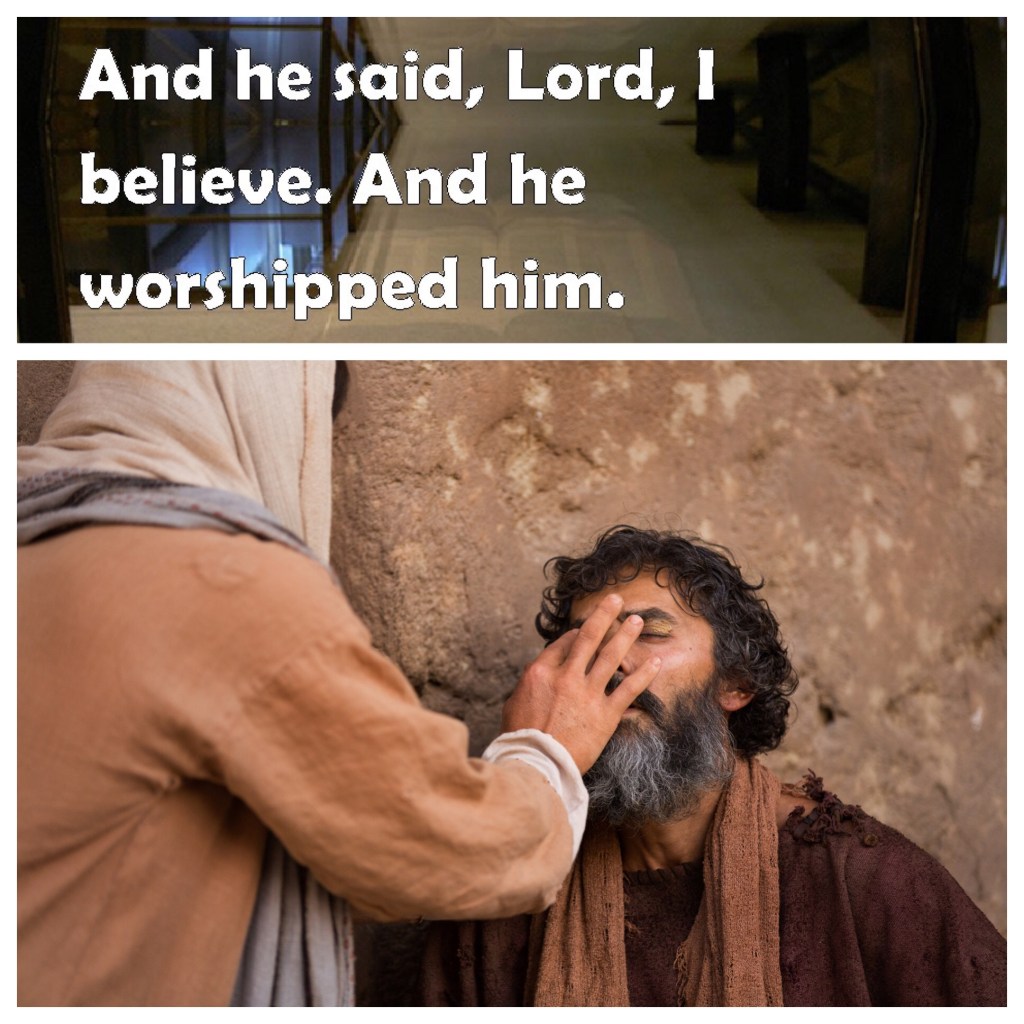

But Thomas appears in two other places in John’s Gospel. One is at the last meal that Jesus shared with his followers, when Thomas asks Jesus a question: “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” This question provokes one of the most well-known sayings of Jesus: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. If you know me, you will know my Father also. From now on you do know him and have seen him.” (John 14:5-7). It is thanks to Thomas that we have this saying of Jesus!

The other time that Thomas is mentioned in this Gospel provides us with another insight into the character of Thomas. He appears early on, in the story of the raising of Lazarus from the dead, as told in chapter 11 of John’s Gospel. In that story, we encounter a rather different Thomas. In that incident, Thomas was a man on a mission who was filled with faith. He spoke with Jesus with the intensity of a fervent believer. He declared that he was prepared to follow Jesus, whatever it cost him.

Faced with a request to travel to Bethany, near Jerusalem, because of the death of Lazarus, Jesus and his followers discuss whether they should make this trip. John’s Gospel tells us that the message of Jesus was so provocative to the southerners in Judea, that they had already mounted a number of attempts to stone him (John 8:59, 10:31).

So the disciples were convinced that if Jesus travelled close to Jerusalem, he would be walking to his death. What to do, they wonder, when this urgent message comes from friends in Bethany: “Lazarus is dead; please come; we need you here!” (John 11:1-8).

At that moment, Thomas springs into action. There is no doubt about it, he declares: Jesus needs to go there; and the disciples need to go with him. “We need to get moving! Come on, why are we waiting?” And from the mouth of Thomas come these incredible words: “We should go too, and die with him” (John 11:16).

Thomas utters the excitable words of a zealous follower of Jesus; he gives a fervent declaration of commitment and trust in the one who had been his guide for many months now. Thomas was not paralysed by fear, not distressed by doubt; here, Thomas was fired up by faith, and committed to a journey that could well lead to death. If Jesus, our master, is going to die—then we, too, should be prepared to die with him! (See https://johntsquires.com/2020/03/23/yes-lord-i-believe-even-in-the-midst-of-all-of-this-john-11/)

This portrayal of Thomas as a committed follower, as a passionate firebrand, is not how we normally remember him, because the story from chapter 20 of the Gospel holds sway. Yet in this earlier story in chapter 11 of the Gospel, it is clear that Thomas has faith, even if it is somewhat unusual, and it is abundantly clear that he is prepared to put his life on the line for what he believes.

So, perhaps we should place this Thomas, the passionate firebrand of John 11, alongside the hesitating, doubting figure that we imagine him to be like, courtesy of John 20. Where are the signs of this passionate, committed, fervent, zealous man of faith, in this encounter? Where was the fiery partisan Thomas living out his faith in the risen Jesus?

I like to imagine (and it is only an imagination … a speculation … as the biblical txt is silent on this point) … I like to imagine that, as the disciples gather behind locked doors, paralysed by their fear, Thomas was not to be found in their midst, because he was back into his regular life, living out his faith in the public arena.

Even after Jesus had been raised from the dead, the transformation of Easter, as we know it, had not really kicked in for the disciples. They were locked into their fear. Where were the disciples living out their faith? It seems they took the line of least resistance, and shared their faith only in the safety of their own group, hidden away, safe in the seclusion of a private home.

And where was Thomas? He was not there. He was out beyond the locked doors, out in the community, in the full gaze of the antagonistic authorities. What was he doing? We are not told; we have to imagine.

Is it feasible to imagine that Thomas was back into his regular routine, going about his business, attending to his daily tasks? That he was seeking to live out his faith, not cowed by the threat of persecution, but firmly holding fast to his belief in Jesus in public? That he was continuing to live as that fiery, fanatical believer who was still willing to put his faith on the line? It is a tempting, enticing way to imagine him.

If Thomas was really the passionately committed believer whom we met in the Lazarus story, then it is quite plausible that this is why he was not with the other disciples, behind locked doors, hiding out of fear.

Perhaps Thomas was wanting to demonstrate his faith to those who did not yet believe. Something had happened to Jesus—the tomb was empty, believers were testifying that he was risen—so he was wanting to show others that his faith had not been shattered.

Where was Thomas living out his faith? In his everyday life, amidst acquaintances and friends—and even enemies. Now that is a model that we would do well to ponder, and imitate, in our lives!

(The image is of Saint Thomas, by Georges de La Tour, a French painter of the 17th century.)

See also