When the priests of Judah returned to their homeland after decades in exile, they wrote down their ideal as to how the people should worship God and honour God in their lives. An integral part of that system of worship was the offering of the tamid, the daily sacrifice, “two male lambs a year old without blemish, daily, as a regular offering; one lamb you shall offer in the morning, and the other lamb you shall offer at twilight.” (Num 28:3). The importance of offering a perfect lamb, without any blemish, was paramount.

In parallel with that, every priest also needed to be “perfect”, with no sign of blemish—“not one who is blind or lame, or one who has a mutilated face or a limb too long, or one who has a broken foot or a broken hand, or a hunchback, or a dwarf, or a man with a blemish in his eyes or an itching disease or scabs or crushed testicles”, according to Lev 21:16–24. Yoiks!

Jesus, of course, picks up on this notion of perfection when he counsels a wealthy young man who claims that he keeps all the commandments, “if you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me.” (Matt 19:21). This “counsel of perfection” was then developed by the evolving Christian tradition, specifically impressing upon candidates for the priesthood their need to aspire to that perfection, through vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience.

My own church, the Uniting Church in Australia, fortunately does not require its ministers to be chaste, or even poor—although we do ask for a good measure of obedience. But the image of Ministry which sits firmly with me as the primary one is not that of “being perfect”; rather, it comes from a story in the ancient sagas of the people of Israel—a story about when Jacob wrestled with a man all night.

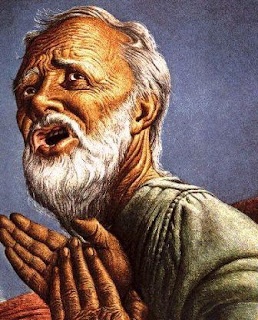

In this story, one of the patriarchs of Israel, Jacob, “wrestled with him until daybreak; and when the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket; and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him.” (Gen 32:25). This is the story which the lectionary provides for our consideration this coming Sunday (Gen 32:22–31).

It is in this story that Jacob, the “supplanter”, is given the new name Israel, “he wrestled with God”. The patriarch Jacob, who would give his name to the people Israel, limped, because of the all-night struggle that he had at this ford in the river. One of my teaching colleagues once wrote a paper in which he developed the image of the minister as the limping priest of God. And so it has been, for me; awareness of my own limping, my emotional and psychological wrestling which has caused psychological and emotional limping, has been an important aspect of my own exercise of ministry.

I have reflected on this personal struggle and my consequent “limping”, with the help of some good company, at

I like to think that gaining insight into my own limping, as difficult as that has been, has enabled me to walk with others as they limped, to understand their pain, to provide compassionate companionship along that way. And, sometimes, to hope that people would come to understand their own limping, and see how it had thrown things out of alignment, and how they might attend to that, and rectify wrongs that may have been occasioned by their limping, their distorted walking patterns, their imperfect ways of operating—even as I regularly reflected on my own walk, my own limping, and how that, in turn, impacted the way that I ministered.

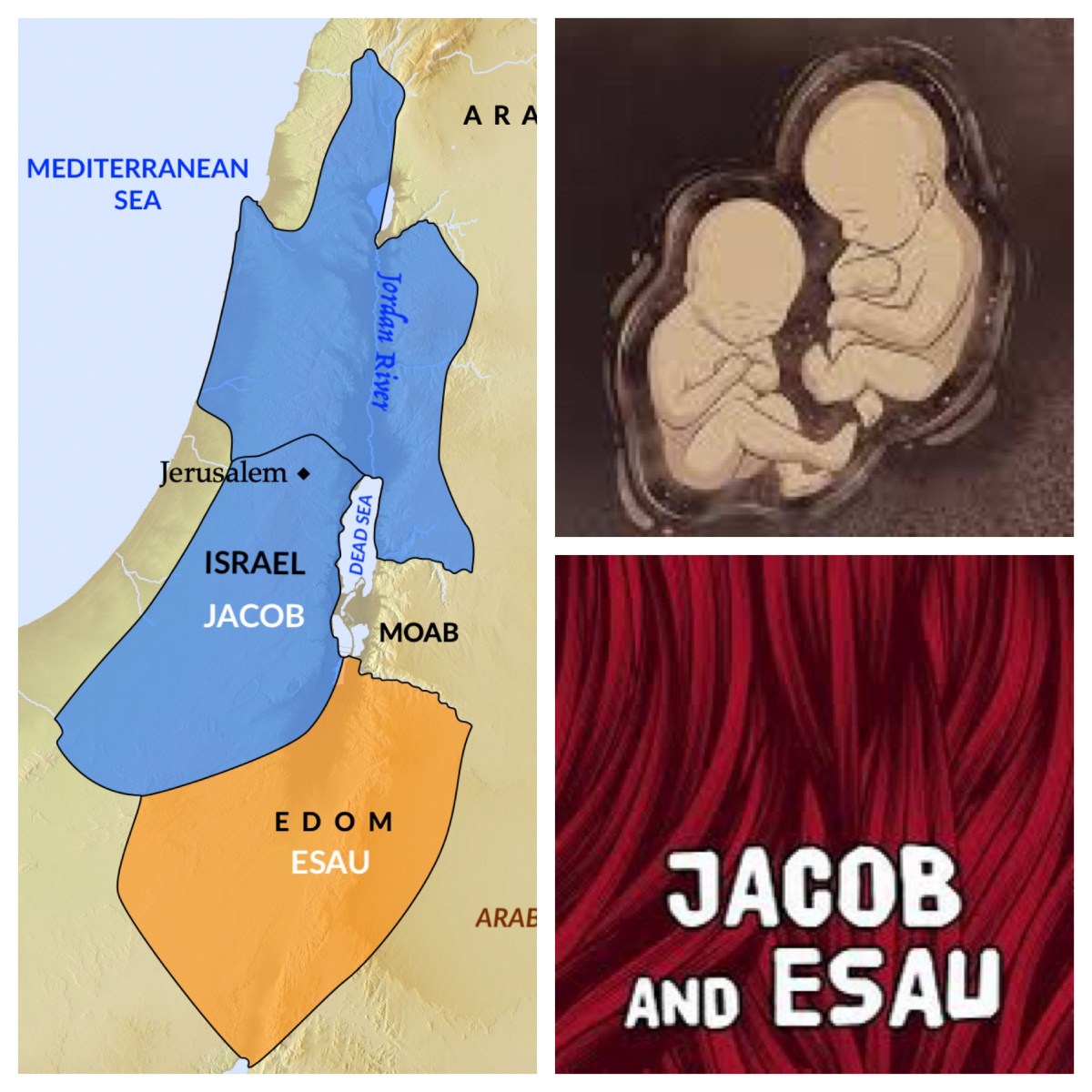

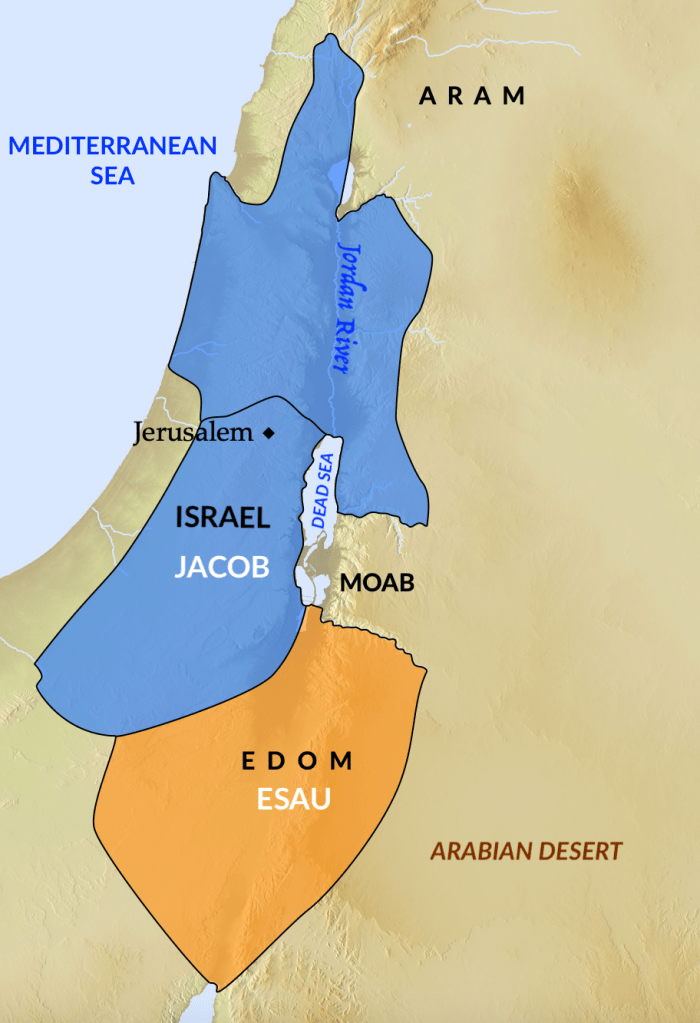

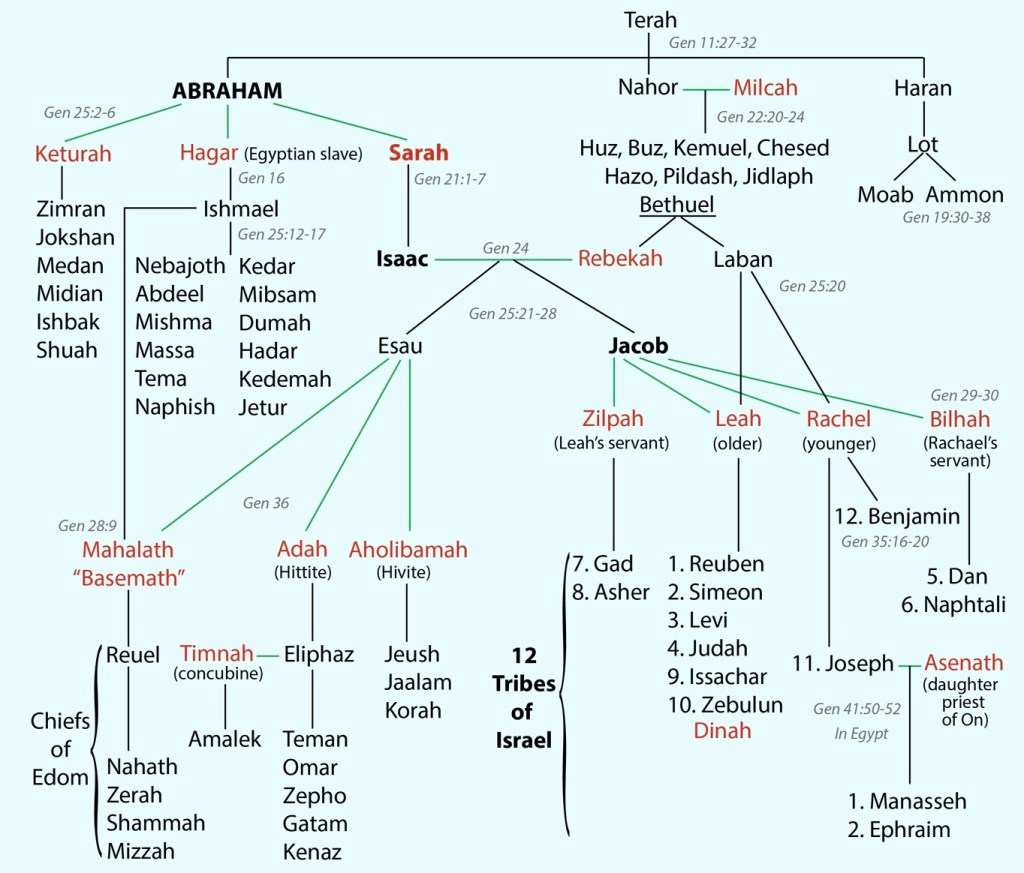

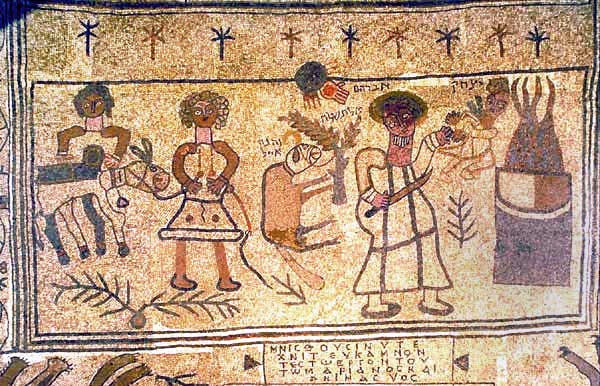

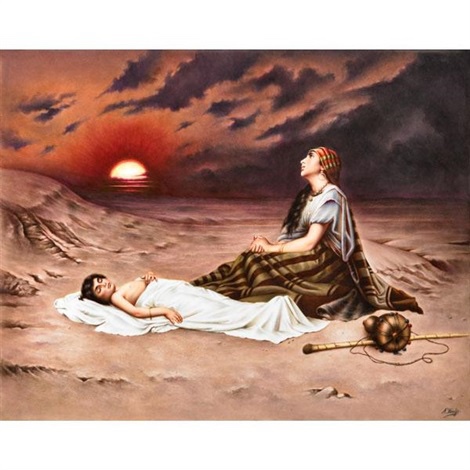

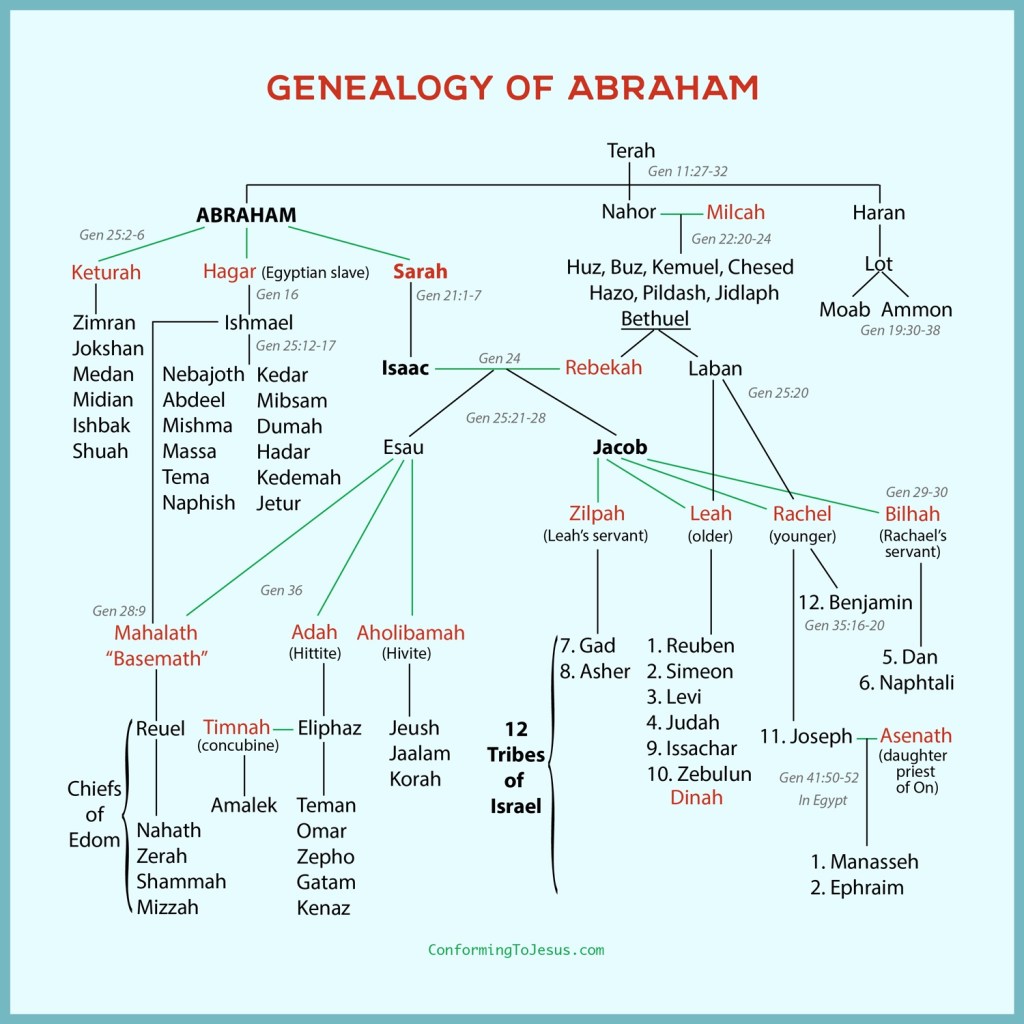

This story of the night-long wrestling and the resulting lifelong limping of the patriarch of Israel was not, of course, an account of an historical event. Like all the stories of incidents involving the patriarchs and matriarchs (Abram, Sarah, and Hagar, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob, Leah, and Rachel, and Joseph) these ancient stories were woven together at the time of Exile for Israel.

They formed an extended narrative that provided a foundational saga for the exiled people, yearning for release from their captivity, a return to their homeland. The saga formed a national mythology, weaving together previously isolated stories that had been passed down from generation to generation, shaped and reworked by skilled storytellers. Together, they created a tapestry that represented the resilience and the hope of the peoples.

Exile in Babylon was a time when the people of Israel, as a whole, had been limping. Invaded and conquered, captured and transported, relocated to an alien landscape amongst a foreign peoples speaking an unknown language and practising strange customs, the people were dislocated, out of joint, and so they limped in their daily lives. (See expressions of their grief in Lamentations, and their anger in Psalms 42–43, 44, and 137.)

The story of Jacob—wrestling with an unknown stranger, struck at the hip, experiencing dislocation, walking with a limp—resonated strongly with them. It was told and retold as “their story”, an oral expression of their personal and national angst. It reminded them that, even in the midst of struggle and opposition, they were still, like Jacob, able to “see God face to face” (Gen 32:30).

*****

That deep level of the myth told and retold by ancient Israelites resonates still with us, today. Opposition and oppression, struggle and the fear of defeat, do not impede the possibility that we might, indeed, “see God face to face”. The story of Jacob at Penuel reminds us of this, and provides a resource for thinking about our own lives, the lives of those we know who are facing challenges, and striving (as Jacob was) to make sense of these experiences.

Jacob wrestled with a man, who turns out to be God. Paul talks about a “thorn in the flesh”, given to him “to keep me from being too elated” (2 Cor 12:7)—although he attributes this to the work of Satan, rather than God. Elsewhere, he encourages the Romans to “be patient in suffering” (Rom 12:12), and informs the Philippians that God “has graciously granted you the privilege … of suffering with Christ” (Phil 1:29).

Paul himself knows about suffering. He catalogues quite a list of what he has endured: imprisonments, floggings, five times being lashed “forty lashes minus one”, three times “beaten with rods”, stoned, becalmed, and shipwrecked; he feared “danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters”, and suffered “in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked” (2 Cor 11:24–31).

From those many experiences of suffering, Paul is able to affirm that “suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts” (Rom 5:3–5). It seems that God is able to work through those difficult experiences—“all things work together for good for those who love God” (Rom 8:28). Suffering, therefore, is integral to God’s work with us.

When Luke, decades later, reports the commissioning of Paul, he reports the divine word to Ananias to tell Paul: “I myself will show you how much he must suffer for the sake of my name” (Acts 9:16). The narrative that follows places Paul in danger in a number of times; in looking back over his missionary activities, Luke has Paul note that he was “enduring the trials that came to me through the plots of the Jews” (20:19), and foreseeing that in the future “the Holy Spirit testifies to me in every city that imprisonment and persecutions are waiting for me” (20:23).

In the narrative that follows, Luke notes that Paul is kidnapped (Acts 21:27), beaten (21:30–3; 23:3), threatened (22:22; 27:42), arrested many times (21:33; 22:24, 31; 23:35; 28:16) and accused in lawsuits (21:34; 22:30; 24:1–2; 25:2, 7; 28:4), ridiculed (26:24), shipwrecked (27:41), and bitten by a viper (28:3). The list correlates strongly with Paul’s own words in 2 Cor 11, noted above. And beyond this, Paul has indicated that “after I have gone, savage wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock” (20:29). Opposition and persecution is endemic in the early stages of the Jesus movement.

Yet all of this takes place under “the whole purpose of God” (20:27)—the overarching framework within which Luke has told the story of Jesus and the movement that grew from his preaching and activities. Luke, like Paul, understands suffering as integral to God’s working in the world. It is a hard message to hear when we are in the midst of the turmoil engendered by suffering; it may be possible, with hindsight, to look back on that suffering and see how good did, in the end, eventuate from it. It seems he was able to see “the face of God” in all of that, as Jacob did long ago at Penuel.

That’s what this story of the wrestling Jacob offered the people of Israel, long remembered from the past telling of stories, now taking on a deeper and more central significance as they returned from the decades of suffering in exile in a foreign land. Out of suffering, something amazingly good is able to emerge. May this ancient story of wrestling and limping, of striving with God and so seeing God “face to face”, offer us the same encouragement in our lives, today.

*****

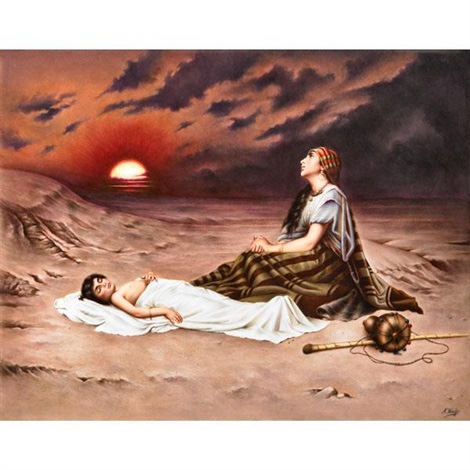

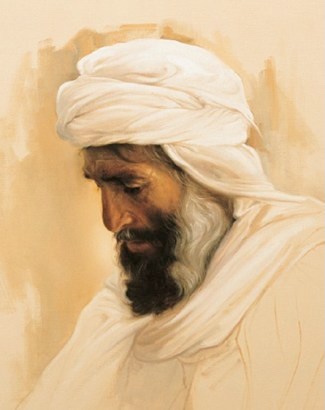

The cover image, “Jacob wrestling with God” by Jack Baumgartner, if from Image. https://imagejournal.org/artist/jack-baumgartner/jacob-wrestling-with-god/