As we move on in the very new year in the church’s calendar, this coming Sunday we celebrate the second Sunday in the season of Advent, and continue our preparations for Christmas—the coming of Jesus, Saviour, chosen one, and Lord (Luke 2:11). During Advent, the lectionary offers a selection of biblical passages designed to help us in our preparations, building to the climactic moment of Christmas Day, when we remember that “the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14).

These scripture passages include a sequence of psalms which orient us to the saving work of God, experienced by faithful people in Israel through the ages. In the psalms, faithful people over the ages have sung of their trust in God and their joy at what God has been doing. These psalms thus bring us to the point of anticipation that we can sense God’s work in the story of Jesus.

Last Sunday, Advent 1, we heard the psalmist’s prayer, “restore us, O God; let your face shine, that we may be saved” (Ps 80:3, 7, 19). In my blog on this passage last week, I reflected on the terms restore, shine, and save. This coming Sunday, Advent 2, we will hear the psalmist sing that “steadfast love and faithfulness will meet; righteousness and peace will kiss each other; faithfulness will spring up from the ground, and righteousness will look down from the sky” (Ps 85:10–11).

“Surely his salvation is at hand for those who fear him, that his glory may dwell in our land” (Ps 85:9) is the key affirmation for this coming Sunday, Advent 2. As we have pondered the theme of salvation so recently, in this blog I turn my thoughts to the theme of glory.

In a story found in the narrative section of the final chapters of Exodus, Moses yearns to know that he has found favour with God: “if I have found favour in your sight”, he prays, “show me your ways, so that I may know you and find favour in your sight” (Exod 33:13). In response, God promises that “my presence will go with you, and I will give you rest” (33:14), but Moses presses his case: “show me your glory, I pray” (33:18). Not just the divine presence, but the glory of God is what Moses seeks.

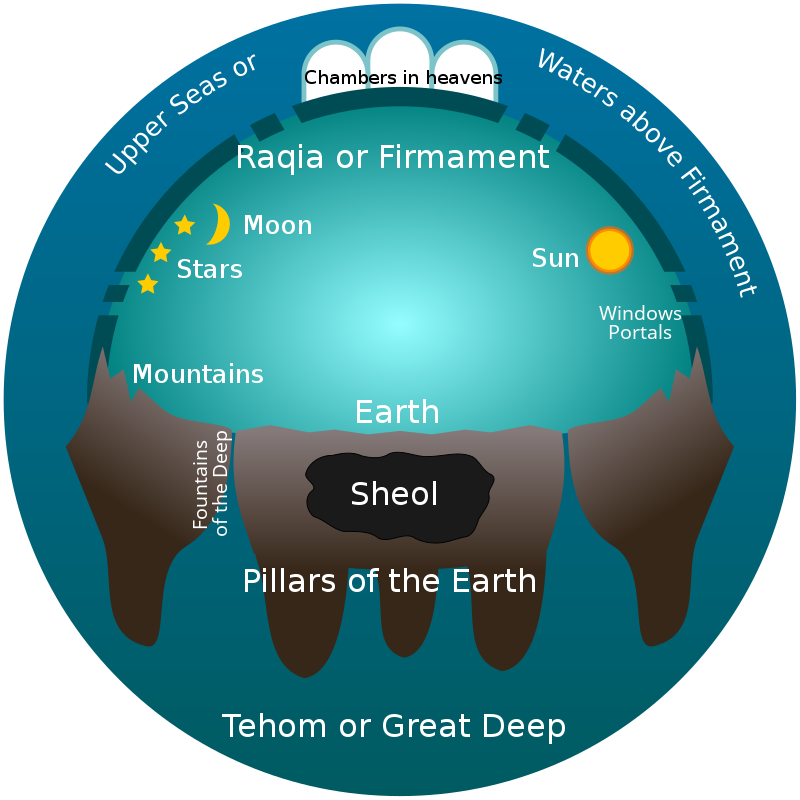

Moses had experienced “the glory of the Lord” on the top of Mount Sinai, when “the appearance of the glory of the Lord was like a devouring fire on the top of the mountain in the sight of the people of Israel” (Exod 24:16–18). That glory had already been seen by the Israelites in the wilderness of Sin (Exod 16:10), and that glory subsequently filled the tabernacle when the people had finished constructing it (Exod 40:34–35).

The closing verse of the book of Exodus notes that “the cloud of the Lord was on the tabernacle by day, and fire was in the cloud by night, before the eyes of all the house of Israel at each stage of their journey” (Exod 40:38). A number of other references to this are made throughout the books of the Torah (Lev 9:6, 23; Num 14:10; 16:19, 42; 20:6; Deut 5:24). This appears to have continued on until the ark of God was captured by the Philistines, for at that moment “the glory has departed from Israel” (1 Sam 4:21–22).

Centuries later, at the time that Solomon prayed his lengthy prayer of dedication of the newly-built Temple in Jerusalem, “when the priests came out of the holy place, a cloud filled the house of the Lord, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of the Lord filled the house of the Lord” (1 Kings 8:10–11; 2 Chron 7:1–3).

The glory of the Lord was then closely associated with the Temple in ensuing centuries, as various psalms attest (Ps 24:3–10; 96:7–8). “O Lord, I love the house in which you dwell, and the place where your glory abides”, one psalmist sings (Ps 26:8); yet other psalms extend the location of God’s glory, exulting that it extends “over all the earth” (Ps 57:5, 11; 72:19; 102:15; 108:5) and even “above the heavens” (Ps 8:1; 19:1; 57:5, 11; 97:6; 108:5; 113:4; 148:13).

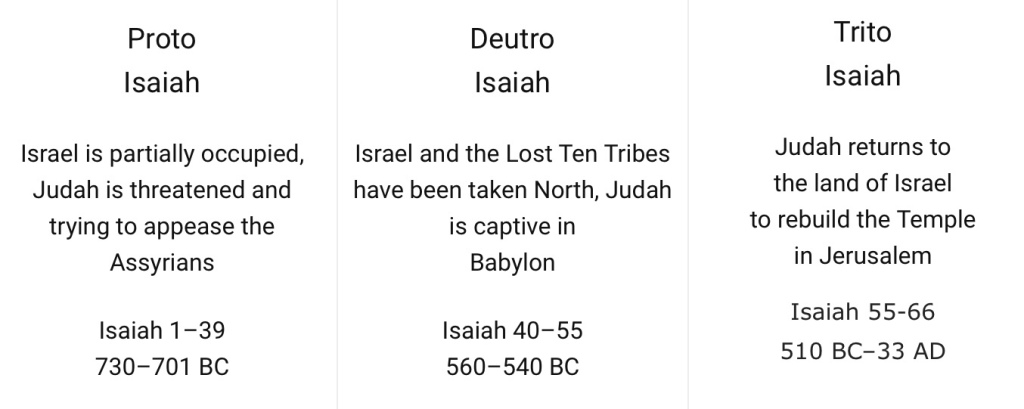

By the time of the prophet Isaiah, this wider scope of the glory of the Lord was sung by the seraphim in their song, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory” (Isa 6:3), whilst a little later another voice sang that “the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea” (Hab 2:14). During the Exile, another prophet, looking to the return of the people to the land of Israel, declared that “the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all people shall see it together” (Isa 40:5).

Another exilic prophet had a series of visions in which “the glory of the Lord” was seen (Ezek 1—39), culminating in a declaration by God that “I will display my glory among the nations; and all the nations shall see my judgment that I have executed, and my hand that I have laid on them” (Ezek 39:21), followed by a vision in which “the Lord entered the temple by the gate facing east”, and at that time “the spirit lifted me up, and brought me into the inner court; and the glory of the Lord filled the temple” (Ezek 44:4–5).

Later still, a prophetic voice during the time of return to the land declared to the people that “the Lord will arise upon you, and his glory will appear over you; nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn” (Isa 60:2–3). And well after that, another prophet attributes to “one like a human being, coming with the clouds of heaven”, the gift of “dominion and glory and kingship, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him” (Dan 9:13–14).

Paul draws on the scriptural idea of the divine glory when he writes to the Romans that “we boast in our hope of sharing the glory of God” (Rom 5:2), and that it is through the work of the Spirit which gives hope to the whole creation that it will “obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God” (Rom 8:21). He tells the Thessalonians that “God … calls you into his own kingdom and glory” (1 Thess 2:12) and speaks of the life of believers as being “sown in dishonour … raised in glory” (1 Cor 15:43).

So Paul advises the Corinthians, “whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do everything for the glory of God” (1 Cor 10:31), and later on tells them that “all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit” (2 Cor 3:18).

And Paul celebrates that God “has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor 4:6), rejoicing that Jesus “will transform the body of our humiliation that it may be conformed to the body of his glory, by the power that also enables him to make all things subject to himself” (Phil 3:21).

Later writers pick up on this motif of believers sharing in the glory of God. Writing in the name of Paul, one affirms that “God chose to make known how great among the Gentiles are the riches of the glory of this mystery, which is Christ in you, the hope of glory” (Col 1:27), while another declares that that God “called you through our proclamation of the good news, so that you may obtain the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ” (2 Thess 2:14). Another writer speaks of God “bringing many children to glory” through Jesus (Heb 2:10), yet another celebrates that God will “make you stand without blemish in the presence of his glory with rejoicing” (Jude 24).

This, of course, leads into the notion in later Christian theology that heaven can be described as the place of glory—the place where James and John wish to be seated alongside Jesus (Mark 10:37), the place where believers are raised (1 Cor 15:43), the place where faithful elders will “win the crown of glory that never fades away” (1 Pet 5:4), the place where the place where Jesus himself is ultimately “taken up in glory” (1 Tim 3:16).

And that glory was most clearly seen, one writer maintains, in Jesus, when “the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory” (John 1:14). For the author of John’s Gospel, the full manifestation of heaven (glory) was made on earth, in Jesus, who was God’s only son, “who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known” (John 1:18).

So the expectation of the psalmist, that the glory of the Lord will dwell in their land, is offered at this Advent time, as we Christians anticipate that God’s glory will again be shown to us in Jesus. It’s a motif that runs through scripture from Moses onwards and is shown forth in striking fashion in the life of Jesus.