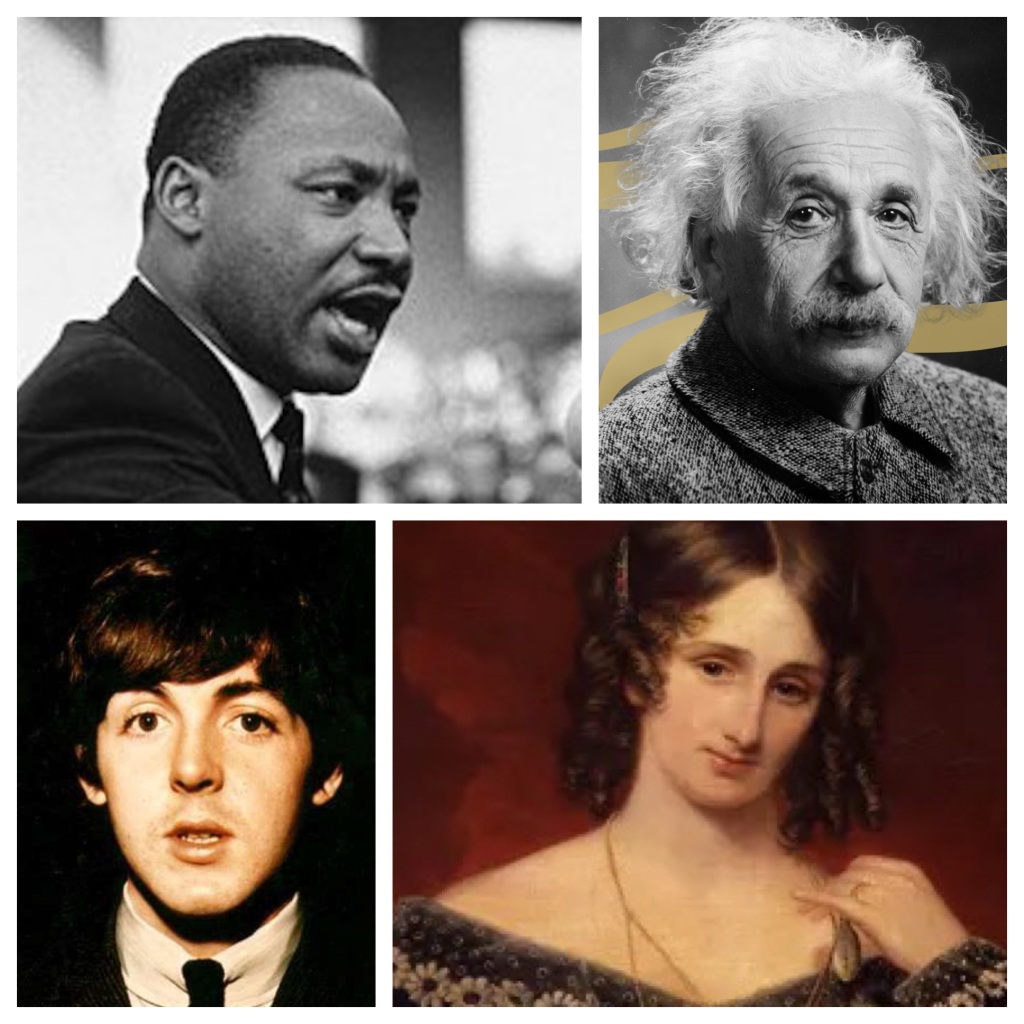

There are some famous dreams throughout history. “I have a dream”, said the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr, speaking in Washington on 28 August 1963, “a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.” That may be the most famous dream in the 20th century.

There have been other significant dreams in modern times. Paul McCartney woke from a dream and wrote the whole score of “Yesterday”. Mary Shelley’s novel “Frankenstein” was inspired by a nightmare. Niels Bohr had a dream in which he saw “the nucleus of the atom, with electrons spinning around it, much as planets spin around their sun”; and thus he developed his theory of atomic structure—a theory later proven by experimental investigation.

In like manner, Albert Einstein is said to have posed his theory of relativity in a dream in which “he was sledding down a steep mountainside, going so fast that eventually he approached the speed of light … at this moment, the stars in his dream changed their appearance in relation to him”; while it was a dream that led Frederick Banting to develop insulin as a drug to treat diabetes.

I found these and other significant modern dreams described at

https://www.world-of-lucid-dreaming.com/10-dreams-that-changed-the-course-of-human-history.html

*****

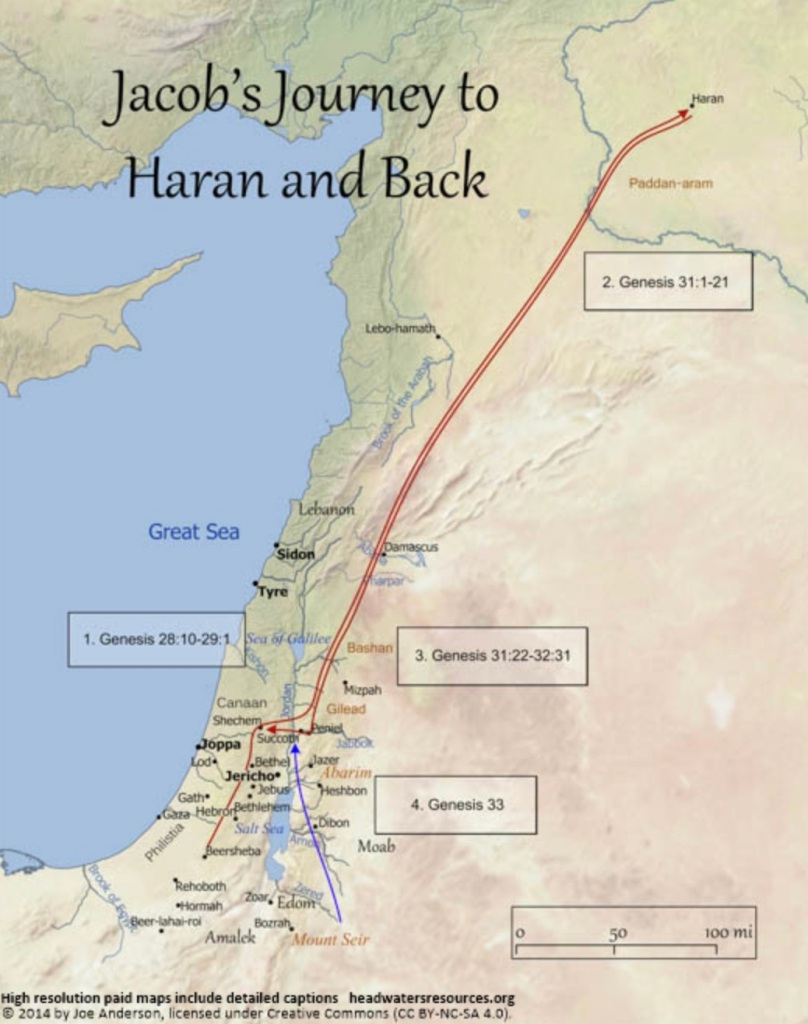

A part of the Hebrew Scripture readings that are offered by the Narrative Lectionary for this coming Sunday (Gen 28:10–17) includes a dream that Jacob had, as he slept one night. He was journeying from Beer-sheba, in the Negeb desert in the south of Israel, which is where he had received a blessing from his father, Isaac. This blessing, as we hear in the other section of scripture offered for this Sunday, was won by trickery,as he took the blessing that was intended for Esau (Gen 27:1–4, 15–23). Which explains the name given to Jacob: he is “the one who supplants” (see Hos 12:3).

Isaac was travelling north towards Haran, the place from which Abram and Sarai had left on their journey towards the land of Canaan, the land which God had promised to him (12:1, 4–5). So the journey that Jacob is undertaking is a reversal, in direction and orientation, of the earlier journey that his grandfather had undertaken.

He was travelling to escape the anger of his brother Esau, after he had tricked their father Isaac into blessing him, Jacob, gifting him with the inheritance that was rightly owed to Esau (27:41). Abraham had travelled south in order to receive God’s blessing. Jacob travels in the other direction after having deceitfully gained his father’s blessing.

We are told that, understandably, “Esau hated Jacob because of the blessing with which his father had blessed him” (27:41), and that he threatens to murder his brother, once “the days of mourning for my father” are completed (27:42). Learning of this hatred, Rebekah advises her son, “flee at once to my brother Laban in Haran, and stay with him a while, until your brother’s fury turns away” (27:43–44).

Whether he had been tipped off about this by Rebekah, or not, Isaac commissions his son to journey back to the homeland—in another case of “don’t marry one of these folks, go back to our homeland and marry one of our own” (as we saw with Abraham and Isaac). Isaac says to Jacob, “you shall not marry one of the Canaanite women; go at once to Paddan-aram to the house of Bethuel, your mother’s father; and take as wife from there one of the daughters of Laban, your mother’s brother” (28:1–2). So Jacob obeys him.

It is on this journey of escape that Jacob has his striking dream. Jacob is not the first to have encountered God in a dream, in these ancestral sagas. Abimelech of Gerar heard from God in a dream (20:3–7). After Jacob’s dream at Bethel (28:12–15), Jacob has a further dream regarding a flock of goats, relating to his inheritance, urging him to return to Isaac in the land of Canaan (31:10–16). At the same time, God appeared in a dream to Laban (31:24), conveying instructions which he disobeyed.

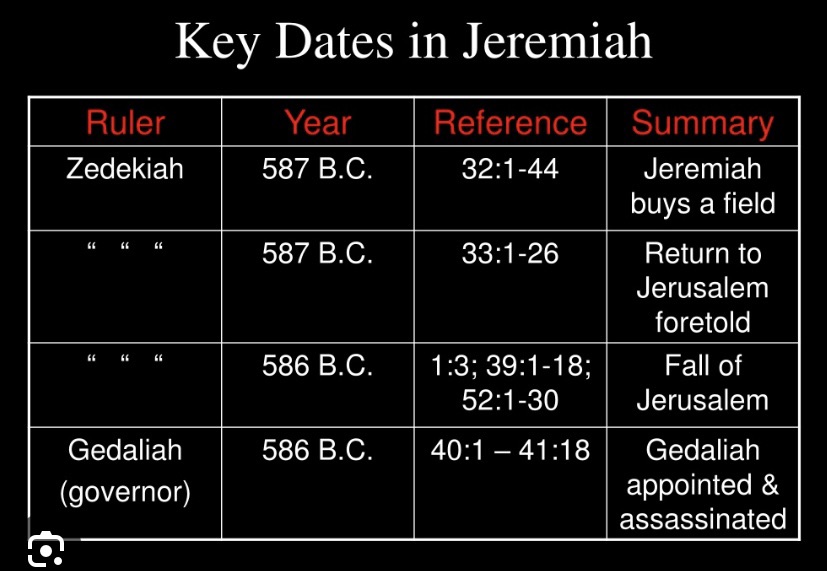

The two great “dreamers” in Hebrew Scripture are, of course, Joseph, one of the sons of Jacob, and Daniel, one of the courtiers of Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, many centuries later. Both men not only dream dreams, but offer interpretations—and interpret dreams that have been dreamt by others. Jeremiah, too, knew of those who claimed that they encountered God in dreams, but warns that understanding those dreams correctly is important (Jer 23:28; 29:8–9).

And dreams as the vehicle for divine communication is found in an important New Testament story, when Joseph learns of the pregnancy of Mary, in Matt 1–2. “Dreaming dreams” is actually an activity inspired by the Spirit, as Joel prophesied (Joel 2:28) and Peter reminds the crowd on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:17).

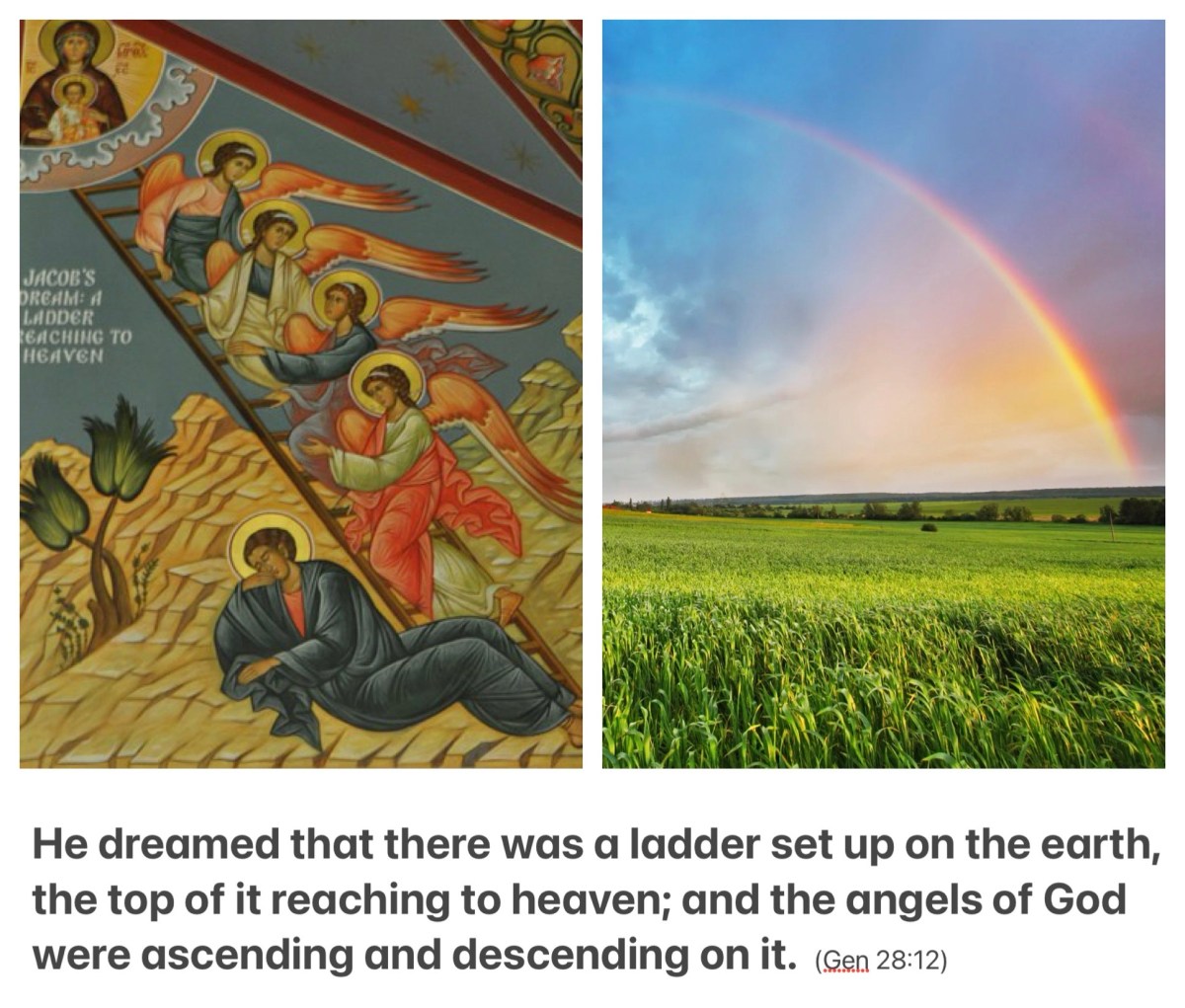

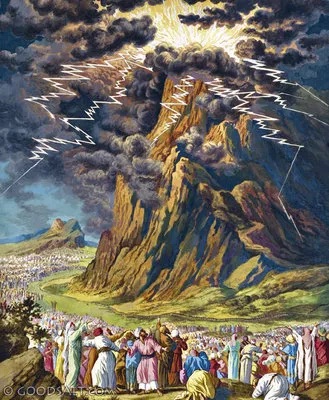

In the story we hear this coming Sunday, Jacob sleeps. As he does, he dreams that “there was a ladder set up on the earth, the top of it reaching to heaven; and the angels of God were ascending and descending on it” (28:12). What do we make of that dream?

In My Jewish Learning, Pinchas Leiser quotes from a book entitled Ruah Chaim (“the breath of life”), by Rabbi Haim of Volozhin. The Rabbi, who lived from 1749 to 1821, was a student of the Vilna Gaon (1695–1785), the pre-eminent sage of Lithuanian Jewry whose ideas were fundamental for the development of modern Jewry. Rabbi Haim writes:

“Our sages come to teach us that we ought not think that, because of our base material, we are truly despicable, like mere plaster on a wall. About this it says, a ladder stationed on the earth–that is Sinai; and its top reaches the heaven–which represents our soul’s life, which is in the highest sphere. There are even souls that see God, and they are the highest of the high, higher than ministering angels, and by this status can the soul cleave to Torah . A whole person is like a tree whose roots are above, and whose trunk extends downward, which is the body, and which is fastened to its supernal roots.”

Pinchas Leiser, a Jewish psychologist and educator, comments: “Thus, Rabbi Haim of Volozhin views Torah learning as a Sinaitic event, since Torah is what connects the heavens and the earth. With Torah, one can ascend and descend between the two spheres. The people who do so are angel-like.”

This is a penetrating insight into the nature of human beings. We are not spiritual beings, trapped in the prison of the material world, as Plato imagined (and as many writers, including Paul, who were influenced by his philosophy, wrote). Rather, we are fully nephesh, creatures of God containing both material and spiritual characteristics. We belong both to earth and to heaven.

The ladder which Jacob saw reveals this true nature, and tells us that we can transport ourselves between the two places, if we would only open ourselves to the possibility. Jacob’s dream was archetypal—it illustrated exactly who we are and how we can live!

And for me, as a Christian reader, it is important to note that this story (and, indeed, many others in Hebrew Scripture) undermines the crass stereotyping of ancient Israelites—and modern Jews—as alienated from God, crushed under unbearable burdens, far from the grace of God. For this ancient story, told orally for many years before it was ever written down, portrays the possibility of a close and enduring relationship with God, accessible from the patriarch Jacob onwards.

Accompanying the dream of Jacob is a sense of the presence of God; the divine speaks to Jacob, assuring him that God will never leave him. Jacob could never go beyond God’s keeping; angels accompany him on his onward journey to northern Mesopotamia, which was his destination (Gen 29:1). These angels keep going up and coming down on the ladder during this journey; more than this, they continue to accompany him for the twenty years he spends in Haran and then travel with him on his return to the land of Canaan (Gen 31:11; 32:1). The story has a strong sense of the enduring, faithful nature of God’s accompaniment of people of faith throughout their lives.

God’s grace is at work in this story. Jacob was an outcast who had deceived his father and lost friends. Seeking God was probably far from his mind; human company was probably what he yearned for. Nevertheless, he was guided by God at this point of need, offering him revealed care and an assurance for the future. Even though he was not expecting grace, grace was unleashed upon Jacob with no word of blame.

So there is a sign of God’s grace in this story—the ladder connecting heaven and earth, on which “angels” ascend and descend at will. God meets Jacob, even as he is running away from family, and perhaps also running away from God; God meets Jacob in a dream. Jacob was fleeing the consequences of his deception of his father. He wanted to be far away from Isaac, whom he deceived, and Esau, from whom he stole the birthright. And in the midst of that journey, God offers a sign of acceptance and grace in this dream.

Indeed, scripture had offered an earlier sign of God’s grace, in the story of Noah. This is a terrible story—God deliberately and intentionally destroys the world, and “starts all over again”. Only Noah and his family, and the animals on his ark, are saved. The rainbow in the sky is the sign of God’s grace for those who have survived, signalling that God will never again destroy the creation.

The ladder represents the commitment that God has, to an enduring connection with human beings, no matter what their situation. It is a sign of God’s grace—for which we can be thankful.