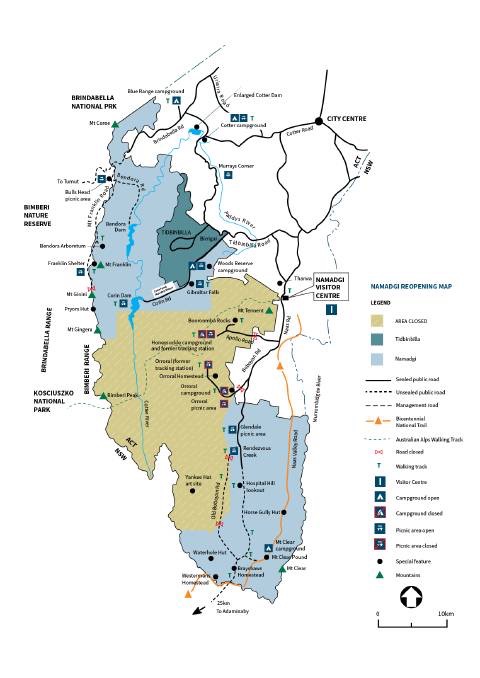

Not far from where we live, to the southwest in what is known as the Brindabella Ranges, there is a large swathe of national park. The Namadgi National Park actually stretches for almost 100 kilometres and it covers just over 100,000 hectares. It is a beautiful “natural” landscape with just a few roads running through it, quite a number of walking trails, and many features of significance.

Because it is so close (the entry point is just a 10km drive from where Elizabeth and I live), we have often ventured into the park for a Sunday afternoon drive; or, as was the case during the pandemic lockdown, for a once-a-week escape from the confines of home and the demands of the ZOOM screen!

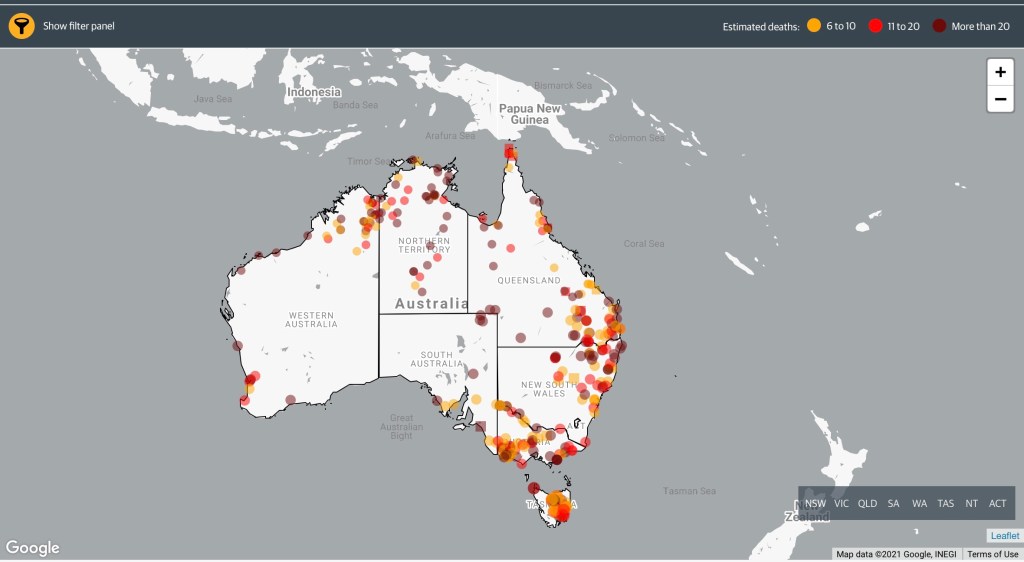

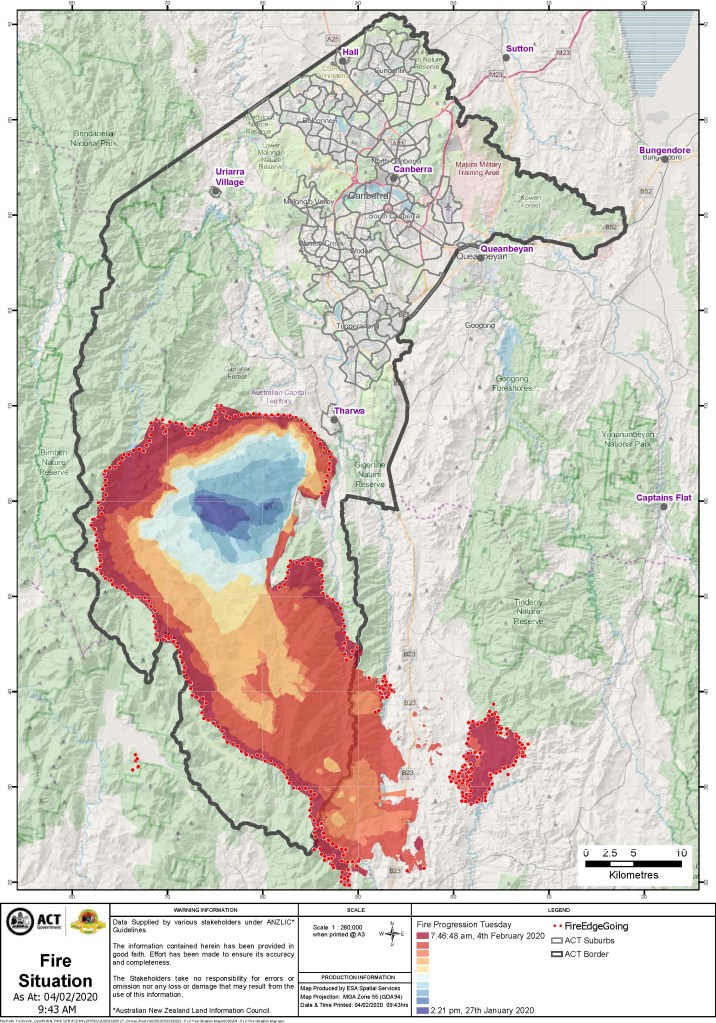

In early 2020, the Orroral Valley bushfire burnt over 80% of Namadgi National Park, or about 86,562 hectares. The fire came perilously close to the urban area where we love, at the southern edge of Canberra. Maps were published showing the danger of embers falling on the suburbs of Gordon and Banks. Plans to evacuate were publicised. We had packed our essentials into a couple of boxes, ready to whisk them away at an early opportunity.

One night, we stood with half of the residents of our street, watching the tops of the Brindabella range mountains that could be seen from our street. There were a number of fires, burning bright in the night. The darkness meant there was no real perspective; the flames, actually 5–6km away, looked like they were just across in the next street. The overhead buzz of planes and copters indicated that the Emergency Services were doing their very best to stop the spread of the fire—as they had been doing for weeks prior to this night.

The fire did not run down the mountain, into the urban area, as it had done in 2003, when a number of suburbs in the south-western area of Canberra were devastated. The memories of that event, scarred deep into the memories of people who had lived in the city longer than we had, were brought back to life in striking and vivid ways, for many we knew.

Just past the entry to the national park, the mountain of Tharwa stands high. It was given the name of Mount Tennent early in the colonial period, when British colonisation began. It was named after John Tennant, a bush ranger who lived in a hideout on the mountain behind Tharwa.

Tennant absconded from his assigned landholder in 1826 and with some others formed a gang which raided local homesteads in the years 1827 and 1828. Eventually he was arrested and transported to Norfolk Island. Tennant was 29 years old when he had been sentenced to transportation to Australia for life in 1823. He arrived in Sydney on 12 July 1824 on the ‘Prince Regent’. Old habits died hard, it would seem. He died in 1837, a year after coming back to Sydney.

Soon after the 2020 bushfire, flooding to the fireground caused significant and widespread damage. The road that ran deep into the national park was closed. Added to the risk of burnt trees falling was the damage done to roads and infrastructure in the floods that occurred some months after the fires. Eventually, the road into the park was opened. We were able to venture back into the bush—to see at close quarters the scarred landscape, the swathes of burnt trees, and the bursts of vibrant green leaves now decorating those burnt trunks.

The savage brutality of what had taken place was evident, from a distance, to those of us who paid attention. Now, at close range, we were able to see just how severe the damage was, as well as how resilient the Australian bush is. New life is bursting forth in so many ways—sadly, not everywhere, as some areas will take much longer to recover—but overall, a picture of verdant health is evident.

******

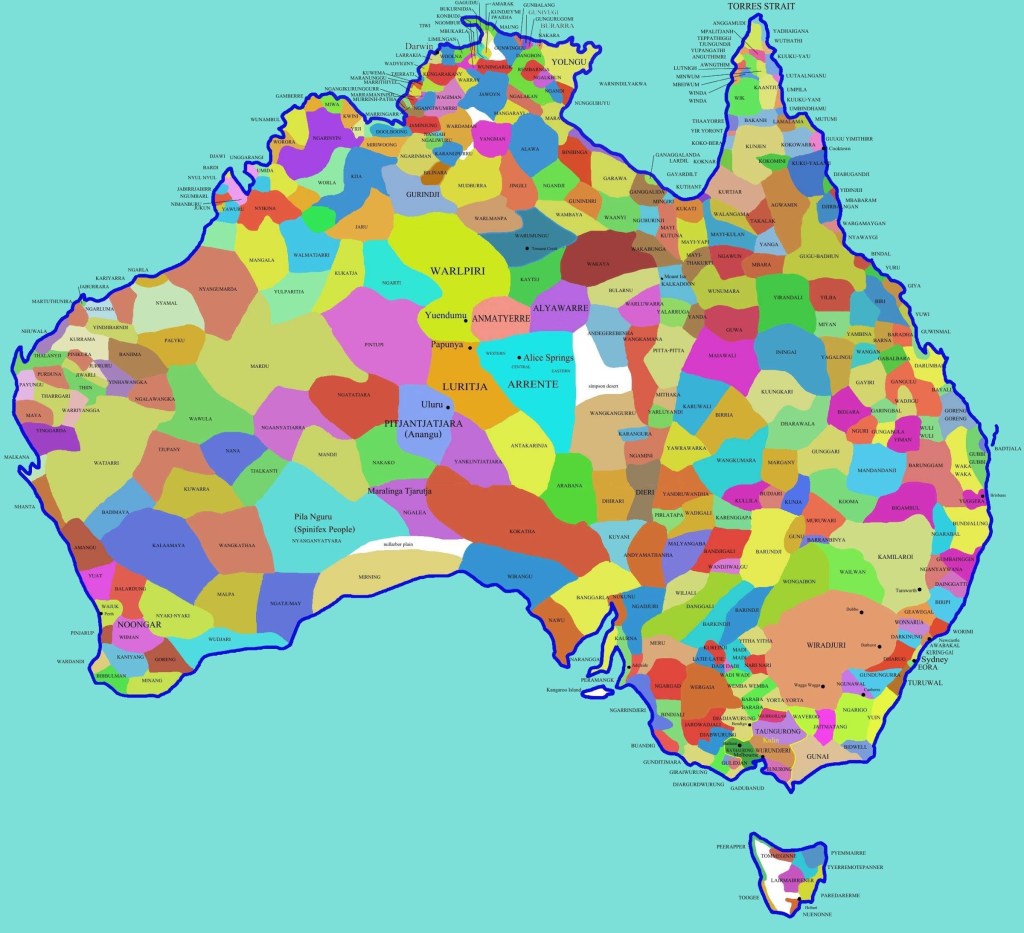

Archaeological excavation and carbon dating of sites in Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve and Namadgi National Park has confirmed an Aboriginal presence in the ACT region 25,000 years ago. Temperatures in the region would have been several degrees lower 25,000 years ago—similar to the conditions on the summit of Mount Kosciuszko today. In other words, seriously cold!!

Bogong Moths would pass through the area in October on their way from breeding grounds on the plains, up to the mountains to hibernate for the summer. The moths are highly nutritious, easy to collect and were in sufficient numbers to warrant large gatherings. Many Aboriginal people from different clan groups and neighbouring nations gathered here for initiation ceremonies, marriage, corroborees and trade.

In fact Jedbinbilla, which means ‘a place where boys become men’ in Ngunnawal language, is situated adjacent to Tidbinbilla and we are told that it was an important place for young boys to learn the first of three stages of man-hood (gatherer, hunter, warrior).

Archaeological surveys of two of the main access routes to the valley area, the Fishing Gap Trail and the path over Devil’s Gap, have found clear evidence of frequent Aboriginal passage. Gibraltar Rocks is a highly significant spiritual site and a corroboree site has been found near the headwaters of Sheedy’s Creek.

Researchers believe the Tidbinbilla valley floor was the focus of a territorial group that survived on the plentiful supply of possum, ducks, wild turkeys, emus, platypus, kangaroo, fish, yabbies and a range of plants, tubers, seeds and fruit.

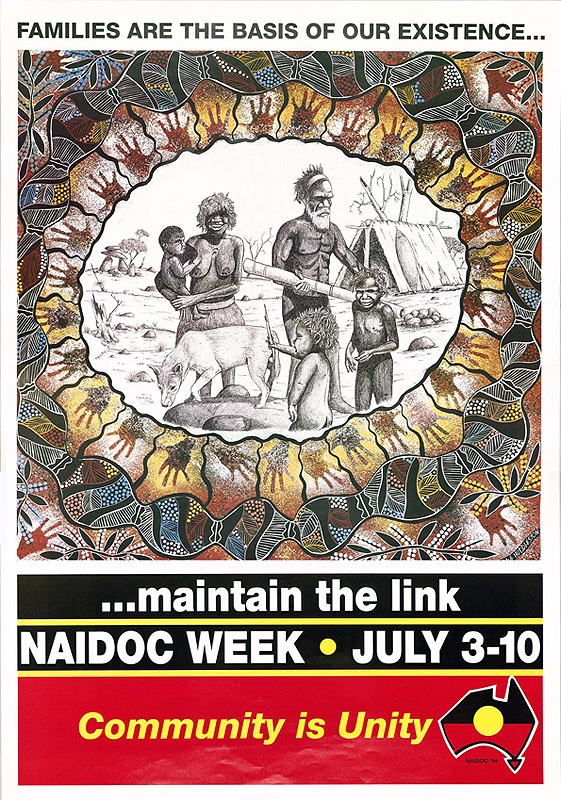

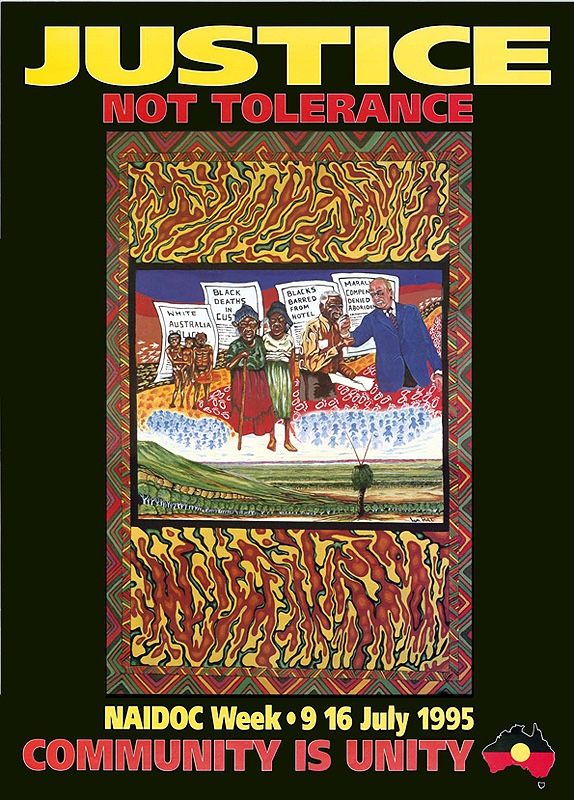

When Europeans first arrived in the area in the early 1820s hundreds of Aboriginal people lived here. The population of Aboriginal people increased at various times during the year when people travelled to the region for social gatherings, ceremonies and seasonal food collecting. European settlement had the same impact on Aboriginal communities in the ACT as it did in other parts of Australia. It brought displacement from the land and exposed people to new diseases such as influenza, smallpox and tuberculosis, from which many died. That, to our shame, is an enduring legacy that we forced into the First Peoples.

Aboriginal heritage sites found in this region include burial places, campsites, rock shelters (with or without ochre paintings), stone arrangements, scarred trees, ceremonial grounds, grinding grooves, quarries and sacred places. At times, Aboriginal occupation is also evident at early European sites such as historic homesteads, cemeteries, reserves and old bridle tracks and coach roads. There is lots of information at https://www.tidbinbilla.act.gov.au/learn/tidbinbilla?a=396477

*****

Men’s sites were often found in the higher peaks of the valley. One of the rock shelters is home to ancient rock art found along a pathway to the Gibraltar rock peak, which is a men’s site. While the mountains in Tidbinbilla are also important to Ngunnawal women, women’s sites were found closer to the river system that twisted through the valley. In some women’s places grinding grooves can still be found on the river’s edge.

Often grand geological formations would be significant to the story of place. Many formations can still be seen today which visually reflect the dreaming story of the valley and its important relationship to the people that have survived and thrived within it for thousands of years. An example of this is the shape of a pregnant woman seen through the contours in the western slopes of the valley and found in the centre of the Tidbinbilla valley is a rock that looks like a perched eagle (Maliyan) the creator spirit of the Tidbinbilla dreaming story.

Tidbinbilla was a key place for Ngunnawal ceremonies, with groups from surrounding areas entering through key points such as Gibraltar Peak, where an elder would light a fire to guide people into the valley. Neighbouring language groups travelled to Ngunnawal Country for the purpose of ceremony, lore, marriage arrangements, trade, sharing of seasonal foods and cultural knowledge.

Tidbinbilla was also a place where young men learnt traditional lore/law, and where they were taken into the mountains as they learnt to become men in the traditional way. Similarly, Ngunnawal women carried out their customary ceremonies in the lower areas of the landscape preparing young girls for womanhood. And as we have noted, the mountains surrounding the valley were home in spring to the migrating bogong moths, which were gathered by Ngunnawal people as a source of food. See

https://www.tidbinbilla.act.gov.au/learn/ngunnawal-culture-and-heritage

and

*****

For earlier posts on learning of country, see