Synod this year was a rich experience of being the church. In the church, we are young and old, and at every point in between. In the church, we are black, brown, and white; we have round eyes and almond eyes, curly black hair and shiny bald pates, flowing blonde hair and cropped short hair.

Around 15 people from the Canberra Region Presbytery attended the three days of Synod this year, in grounds of one of the Uniting Church schools, Knox Grammar, in Wahroonga. We were part of over 300 people who participated in the meeting.

During Synod, we worshipped. Each day began with worship, supported by an amazingly-gifted group of musicians, filled with prayers and songs and scripture and silence. Each day ended with worship, with an act of reflection based on doing, not just listening.

At regular points, we were invited to pause, reflect, share, or pray about what we had been considering. In one session, we prepared for prayer by writing words of gratitude on a piece of paper, folding it into the shape of a plane; and then we prayed by sending the plane shooting through the air to the accompaniment of a resounding AMEN!

During Synod, we listened. Principal Peter Walker led three studies on scripture, drawing from the letters of Paul as well as medieval and reformed church leaders, focussing us on the Christ who is the unifying centre of our diversity. Pastor Jon Owen spoke of working on the ground with people, in inner city Melbourne and now, in his current role with Wayside Chapel in Sydney.

And we listened some more. Karina Kreminski inspired us to consider “what in the world is God up to?” in our neighbourhood. And Josh Gilbert, a young indigenous farming man, spoke with passion and commitment about how it is possible to have an impact, to make the changes, that will enable us to reduce our carbon footprint and move towards a healthier environment for future generations.

During Synod, we deliberated. Each day we listened to proposals, deliberated about clauses, discussed action plans, explored and debated and applauded and sighed and waved cards, making decisions about matters of significance within the church and across our society. This is the business component of Synod, and it is always important to give adequate time to prayerful consideration and thoughtful discussion of the array of proposals presented to the Synod.

In two sessions, we met in smaller Discernment Groups of about ten people, to give focussed attention to one or two specific matters each day. Feedback from each group is then collated and fed back, the next day, to the Synod meeting in,plenary session. This is an important part of the way that the Uniting Church attends to business in its councils. Each person’s view is important, and Discernment Groups provide an opportunity for everyone, even the shyest person, to contribute to the making of policy.

One thing that the Uniting Church does well, is advocate. On the first day, we spent a productive time exploring a comprehensive report on what is being done, and considering what might be done, to advocate for the needs and of particular groups in our society. The Uniting Church has been the lead body in seeking fair treatment in relation to illicit drug usage, and very active in the Give Hope campaign for Asylum Seekers and Refugees.

The Uniting Church has been involved in the broad community movement to seek better arrangements for Affordable Housing in Sydney, and relentless in pursuing responsible living within our environment and climate change advocacy. There has also been involvement in policy development relating to domestic and family violence, as well as the scourge of poker machine gambling. We were asked to consider what other issues required attention.

In one session, a large group of younger members of the Synod gathered on the stage, along with the Uniting Earth Advocates and the Uniting Director of Mission, Communities and Social Impact. They made a compelling presentation which convinced the Synod to adopt a Climate Change Strategy Plan. This has multiple elements, each of which needs significant and sustained buy-in from all of us across the Synod.

We adopted another proposal which urges the people across the Synod to Focus on Growth in a wide variety of ways: growth in discipleship and growth in relationships, as well as growth in numbers and in impacts. This is to be a priority for Congregations and Presbyteries in the coming years.

We approved a Renewed Vision for Formation, to engage people across the church in forming leaders in local contexts, discerning those gifted for ministry, and providing deeper Formation all pathways for those candidating for a specified ministry within the church.

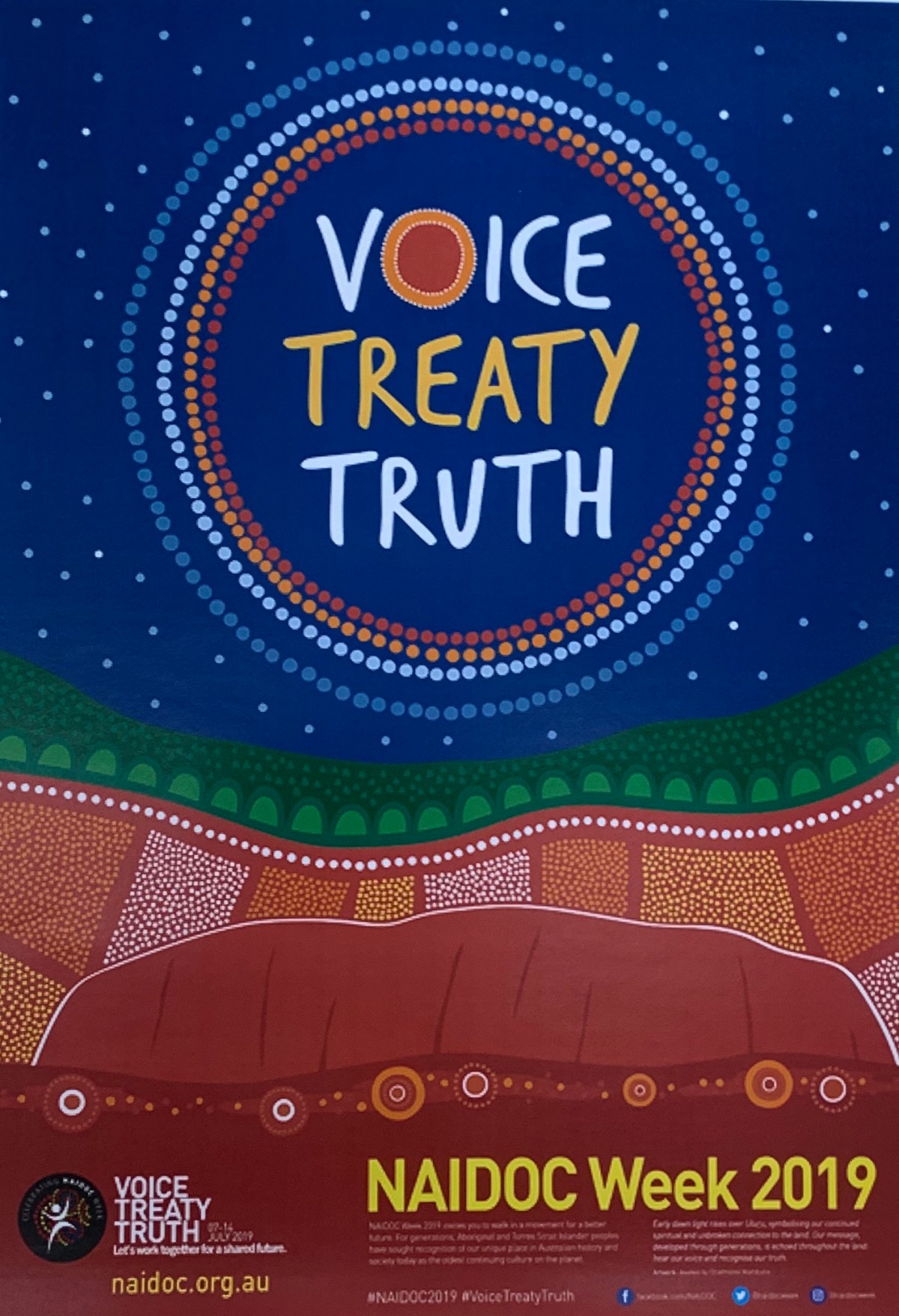

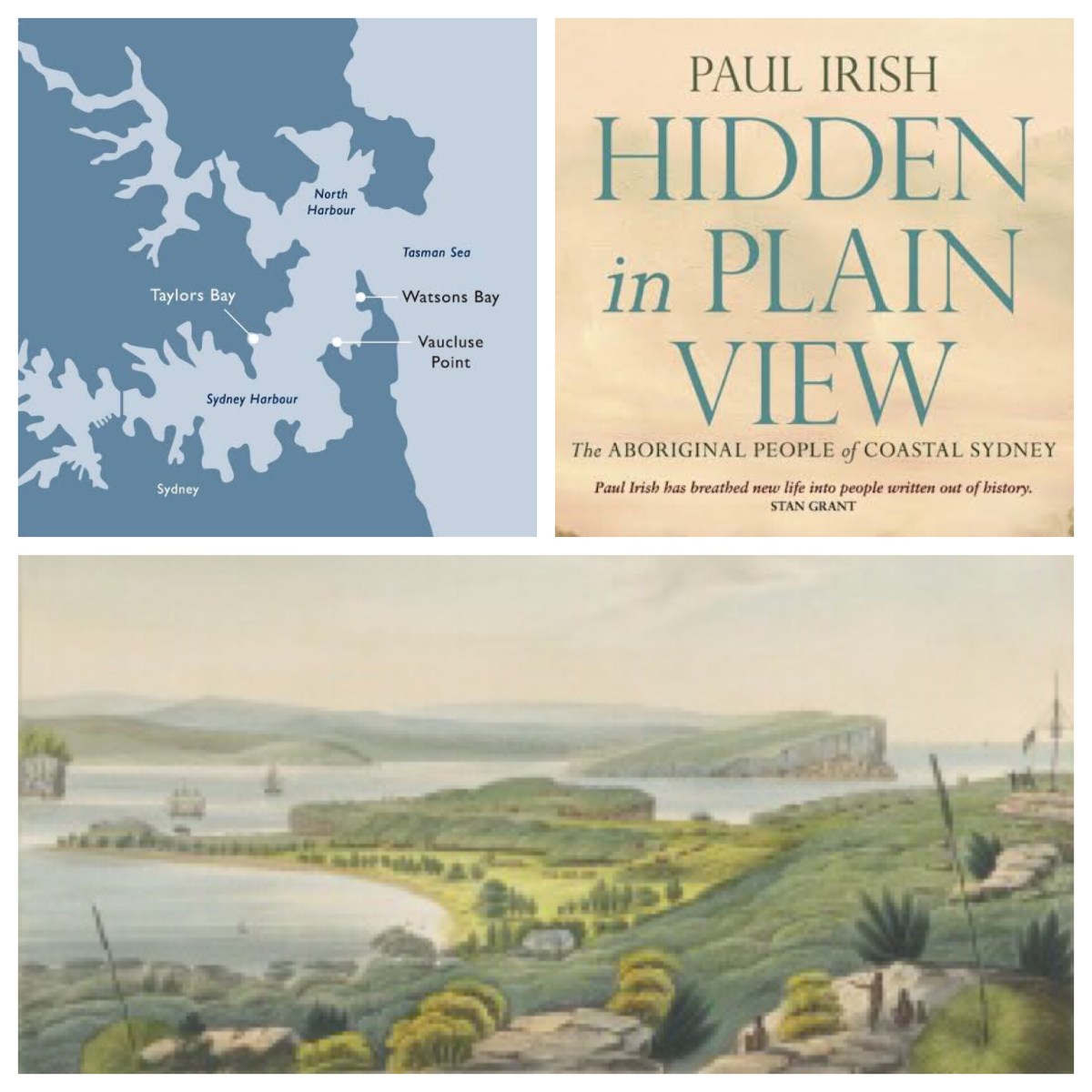

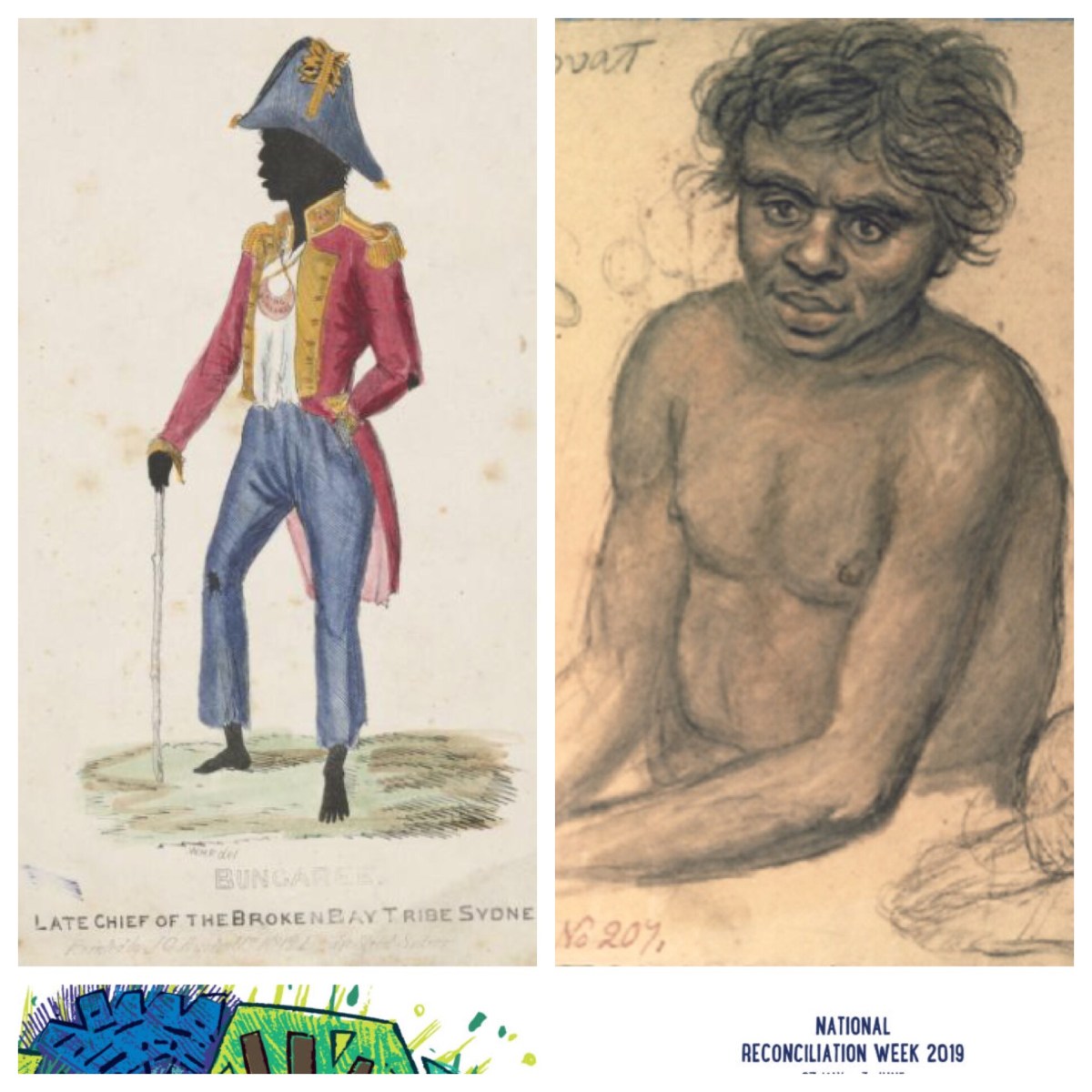

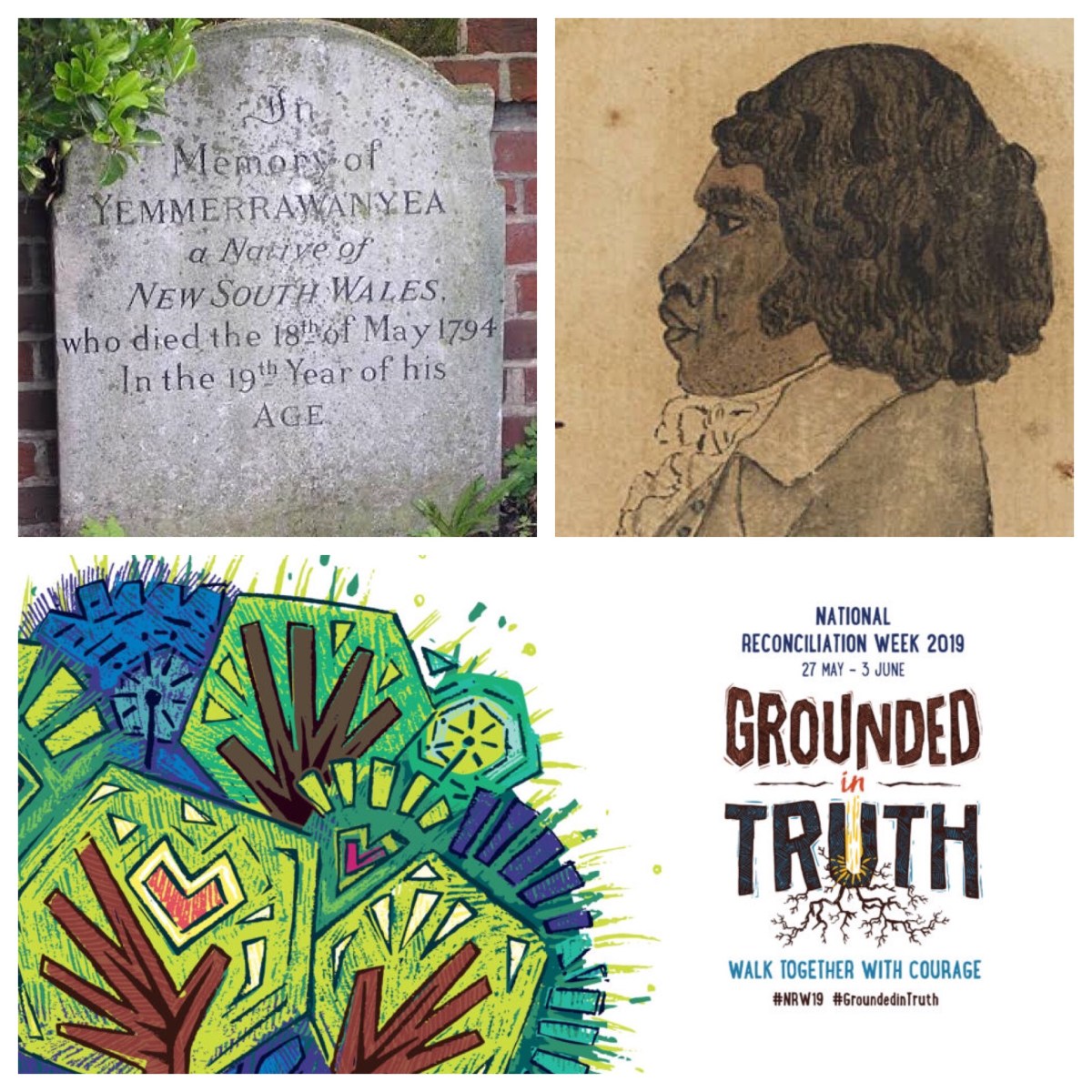

And we enthusiastically supported a set of proposals, shaped around the theme of NAIDOC Week 2019 (Giving Voice, Telling Truth, Talking Treaty) to encourage people across the church to become better aware of how to relate to First Peoples and to advocate with our governments for treaties to be established with First Peoples nations.

During Synod, we learnt and rejoiced. There were evening events outside the ‘business sessions” during Synod: the screening of the powerful documentary ‘Half a Million Steps’, highlighting the plight of people struggling to access drug treatment as part of the Uniting-led Fair Treatment campaign; and a Saturday night festive Revivify Worship Event with music from various cultures and a keynote address from Jon Owen.

During Synod, we made a bunch of regular administrative decisions. People were elected to vacancies on each of the four Synod Boards, as well as a new group of twelve people to serve as members of the Standing Committee of the Synod until the next meeting in 2020.

In a most unusual (but understandable) move, Synod decided to extend the term of the Moderator, Rev. Simon Hansford, by another three years. With this extension, the Moderator’s term will now finish in 2023. The combination of significant turnover of senior leadership within the Synod, and changing expectations in society, were the motivators for this decision.

Members of Synod are drawn from all fourteen presbyteries across NSW and the ACT, as well as from the Congress of First Peoples. Not every congregation has a person present at Synod—some have multiple members present. There is always an equal number of ordained and lay people attending, and CALD groups were particularly in evidence throughout the meeting—Korean, Tongan, Fijian, Samoan, Kiribati, and no doubt a number of other ethnicities. It was great to see the substantial number of younger delegates present. Almost one third of the membership was attending their first Synod meeting. We well depicted the diversity of people of faith in our contemporary church.

The meeting ended with a final worship service, featuring lively music, moving prayers, and thoughtful reflection on the three days of this gathering.

Synod meetings always serve an important personal function as well. After a couple of years interstate for Elizabeth and myself, this meeting offered us both opportunities to catch up with friends and colleagues from many different locations, as well as to meet new people and find out about the challenges and opportunities facing these folk. Those opportunities were greatly appreciated. It also offered opportunity to network in strategic ways about specific matters in our current placements. So that made attending the Synod a most worthwhile, enjoyable, and productive experience.

There are reports on many of the matters noted in this report, on the Insights website. Go to http://www.insights.uca.org.au/news

See also https://johntsquires.com/2019/07/07/giving-voice-telling-truth-talking-treaty-naidoc-2019/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/07/19/climate-change-a-central-concern-in-contemporary-ministry/

https://johntsquires.com/2018/09/19/discernment/

https://johntsquires.com/2018/11/26/the-uniting-church-is-not-a-political-democracy/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/06/18/the-dna-of-the-uca-part-i/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/06/18/the-dna-of-the-uca-part-ii/