“Is it a boy or a girl?” For many years, that has been a standard question after a woman has just given birth. In more recent times, due to the advances in medical technology that have occurred, that question can no be put to pregnant couples: “Is it a boy or a girl?” Ultrasounds can now apparently reveal the gender of the foetus from about 11–13 weeks.

So it is always a surprise when the answer to that question is not “boy” or “girl”, but “both”—in the case of male-and-female twins—or “two boys” or “two girls”, as the case may be, in other instances.

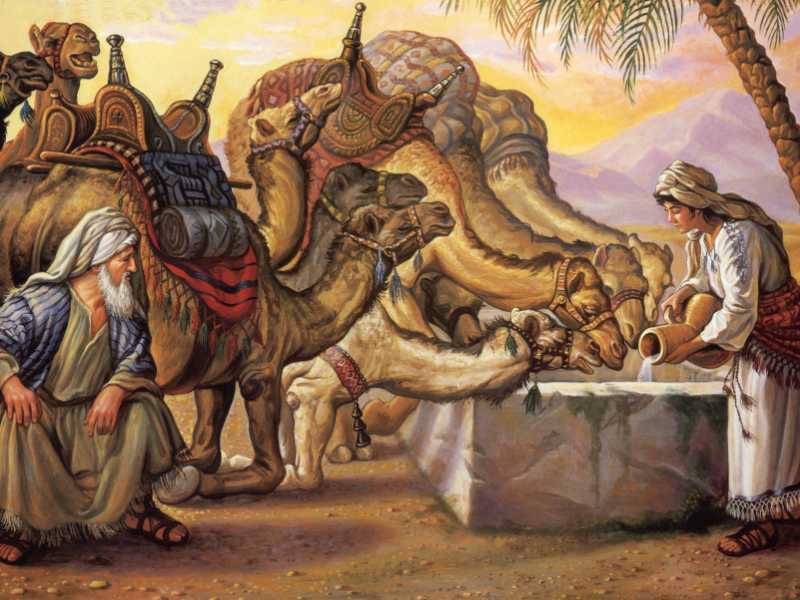

“Isaac prayed to the Lord for his wife, because she was barren; and the Lord granted his prayer, and his wife Rebekah conceived”, we read in the Hebrew Scripture passage offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday (Gen 25:19–34). Here, we meet another barren woman in the ancestral sagas of Israel. Years before, Isaac’s mother Sarah had been barren, and that state had lasted for many decades—and indeed “the Lord had closed fast all the wombs of the house of Abimelech because of Sarah, Abraham’s wife” (20:18).

And other barren women are yet to come in those ancestral sagas; the rabbis note that there are seven significant women who were infertile in scripture: Sarah (Gen 11:30), Rebekah (Gen 25:2), Rachel and Leah (Gen 29:31), Manoah’s wife (Judg 13:2), Hannah (1 Sam 1:2), and Zion (Isa 54:1). The eventual gifting of children to these seven is related by the rabbis to a textual variant in 1 Sam 2:5, reading “the barren has borne seven” as “on seven occasions has the barren woman borne”.

The seventh in this list, Zion, is not an individual who lived in the past but is the personified Israel of some future time, based on Second Isaiah’s characterization of Zion as a barren woman: “Sing, O barren one who did not bear, burst into song and shout, you who have not been in labour; for the children of the desolate woman will be more than the children of her that is married, says the Lord” (Isa 54:1).

The result of God’s intervention, in Rebekah’s case, was a surprise: not one, but two, boys! But the time for shouting with joy is short, for poor Rebekah is given sobering news about her twin boys: “two nations are in your womb, and two peoples born of you shall be divided” (25:23a). Not only that, but “the one shall be stronger than the other, the elder shall serve the younger” (25:23b).

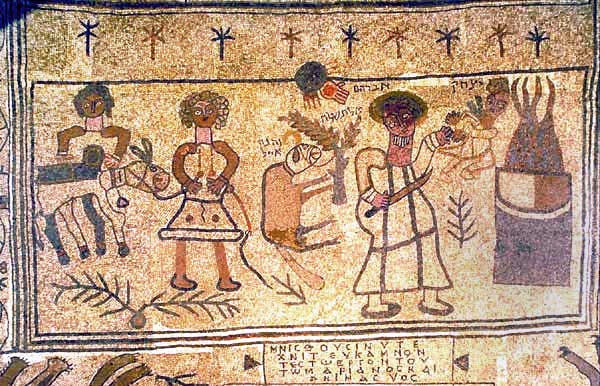

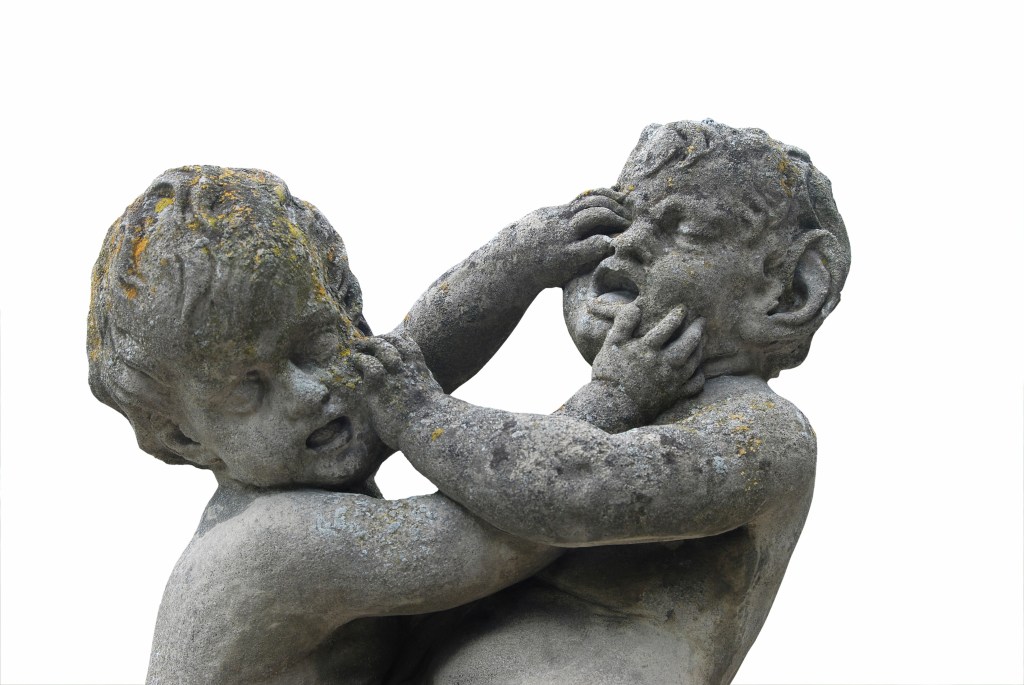

Isaac and Rebekah have brought into the world two boys—the older, who “came out red, all his body like a hairy mantle”, who was named Esau (meaning “hairy”), and the younger, hot on the heels of his brother (literally), who followed immediately “with his hand gripping Esau’s heel”, who was named Jacob (meaning “supplanter”).

The other twins that are (in)famous in Hebrew Scripture are Perez (“a breach”) and Zerah (“brightness”), twin sons of Tamar, daughter-in-law of Judah, who had liaised with her whilst visiting his sheepshearers (38:12–30). In the New Testament, “Thomas the Twin” is one of the named twelve disciples (John 11:16; 20:24; 21:2), although his sibling is never identified.

Who calls their child “the one who supplants” at the moment of birth? The names, identified in the narrative at the moment of birth (25:25–26), must surely be retrojections into the story, for the names prefigure events as they later transpired. This story, like many of the stories in the book of Genesis, is an aetiological narrative—a story told to explain how things are as they are.

I have noted previously that such narratives tell of something that is said to have occurred long back in the past, but the focus is on present experiences and realities, for “such explanations elucidate something known in the contemporary world by reference to an event in the mythical past”.

The name of Jacob is given to explain his role in the story that is unfolding: first, Jacob tricks his brother Esau to sell his birthright to him (25:29–34). As firstborn, Esau should have inherited from Isaac; now, Jacob has supplanted him (as his name indicates). In subsequent passages that the lectionary skips over, Jacob deceives his father in order to receive the blessing that was intended for the firstborn (27:1–29).

As Esau subsequently laments to his father, “Is he not rightly named Jacob? He has supplanted me these two times: he took away my birthright; and look, now he has taken away my blessing” (27:36). His fate as the one no longer relevant for the continuation of the family line, promised to Abraham and continuing through Isaac to Jacob, now, comes when he marries “Mahalath daughter of Abraham’s son Ishmael, and sister of Nebaioth, to be his wife in addition to the wives he had” (28:9). See my earlier reflections on Ishmael at

So Jacob lives up to his name. And we know well his name, through the seven places in the New Testament where we find formulaic references to the three patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Mark 12:26; Matt 8:11; 22:32; Luke 13:28; 20:37; Acts 3:13; 7:32), as well as the many references to them together in the Hebrew Scriptures (Gen 50:24; Exod 2:24; 3:6, 15, 16; 4:5; 6:3, 8; 33:1; Lev 26:42; Num 32:11; Deut 1:8; 6:10; 9:5, 27; 29:13; 30:20; 34:4; 2 Ki 13:23; Jer 33:26).

Yet the irony is that Jacob’s name is later changed, to a name that would become still more famous—and live on into the modern world as the name of the nation of people who see themselves as the chosen ones. After wrestling all night with a man at the ford of the river Jabbok, Jacob is told “you shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with humans, and have prevailed” (32:28; see Pentecost 10A).

And that story, of course, is yet another aetiological narrative; for the name given, Israel, means “the one who strives with God”, which was the fate of Jacob on that night, and of the people of the nation over the centuries and millennia to follow. So the story of this change of names is an important one to remember and pass on.

In this story, however, the names of the boys born to Isaac and Rebekah are the key point: one is born hairy, the other is a supplanter. And the trick that he played to gain the inheritance of his father plays a crucial role in the self-understanding of the people who were telling this story, and passing it down the generations, and remembering it to this day. It is the second-born (even if just by a few seconds in time) who supplants the firstborn.

So Isaac was preferred over his older brother, Ishmael. Jacob gained the birthright of his (slightly) older twin brother Esau. Joseph gained ascendancy over his many older brothers. Jacob, at the end of his life, blessed the younger son of Joseph, Ephraim, rather than his older son, Manasseh. Moses was chosen as God’s spokesperson in Egypt, in preference to his older brother, Aaron. And instead of any of the seven older sons of Jesse, the ruddy, handsome youngest, David, received the blessing of the prophet Samuel to be anointed as king. In each case, it was the younger who was preferred over the older—a striking set of stories to be remembered!

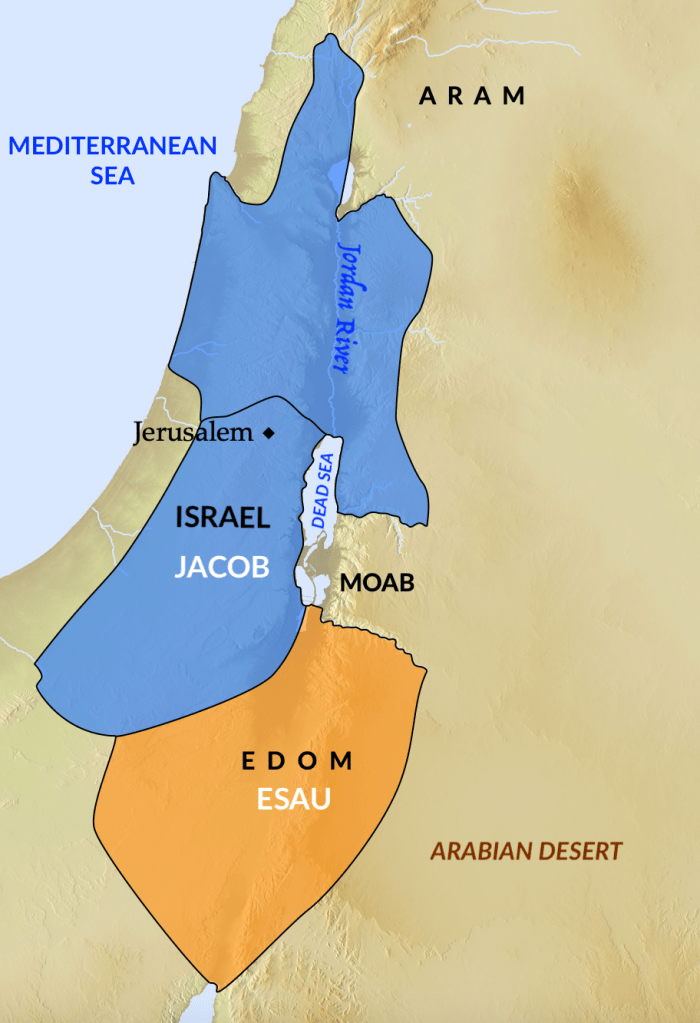

Esau, we are told, is the ancestor of the Edomites, to the south of Israel (Gen 36:1–43), whilst the descendants of Jacob (Gen 25:19–28), of course, populated the land of Canaan, known as Israel, after the name later given to Jacob (Gen 32:28; see Pentecost 10A).