There is intense emotion in Israel and in Gaza. Hundreds of Israeli families are mourning the deaths of the 1200 people killed on 7 October 2024, the deaths of scores (perhaps even hundreds) of the 251 hostages taken on that day, the 468 Israeli soldiers who have died since that day.

At the same time, the families and friends of the nearly 68,000 Palestinians killed in Gaza over the same timeframe, and especially the 20,179 of them who were children, are experiencing a similarly intense sense of grief.

It’s a region bubbling with all that unrequited grief brings: sorrow, despair, anger, a festering hatred, a resolve to “never forget”. It’s hardly a fertile ground for peace to flourish. Will the “peace agreement” hold? Will the “peace plan” prove to be effective?

As the latest group of hostages return to Israel, giving understandable joy to their families and friends, and hope for an enduring peace in the region, let us not forget that the displaced Gazans returning to the homes will find 78% of the structures in Gaza are damaged or destroyed; 22 of the 36 hospitals in Gaza have been destroyed, and some of the remaining 14 hospitals are only partially functional; and 1.5% of the viable cropland in Gaza is able now to be used for cultivation. They are not simply “coming back home”; they are returning to scenes of devastation and destruction that will surely intensify their despair.

This is the third ceasefire since the events of 7 October 2023. Will it last? Relations between many (not all) Israelis and Palestinians are incredibly complex, and an enduring peace amidst the aggressive antagonism and intensifying hatred that has marked recent years (indeed, decades) does not give me confidence.

The US has provided $21.7 billion of military aid to Israel since 7 Oct 2023. If Trump really wants peace, he could cease all future military aid and divert funds to the needs in aid supplies, health, and restoration of infrastructure in Gaza.

I’ve taken these figures from an article by NPR, a media organisation in the USA that is “an independent, nonprofit media organization … founded on a mission to create a more informed public”. (Thanks to Megan Powell du Toit for the link.)

https://www.npr.org/2025/10/13/g-s1-92205/ceasefire-gaza-war-key-figures?

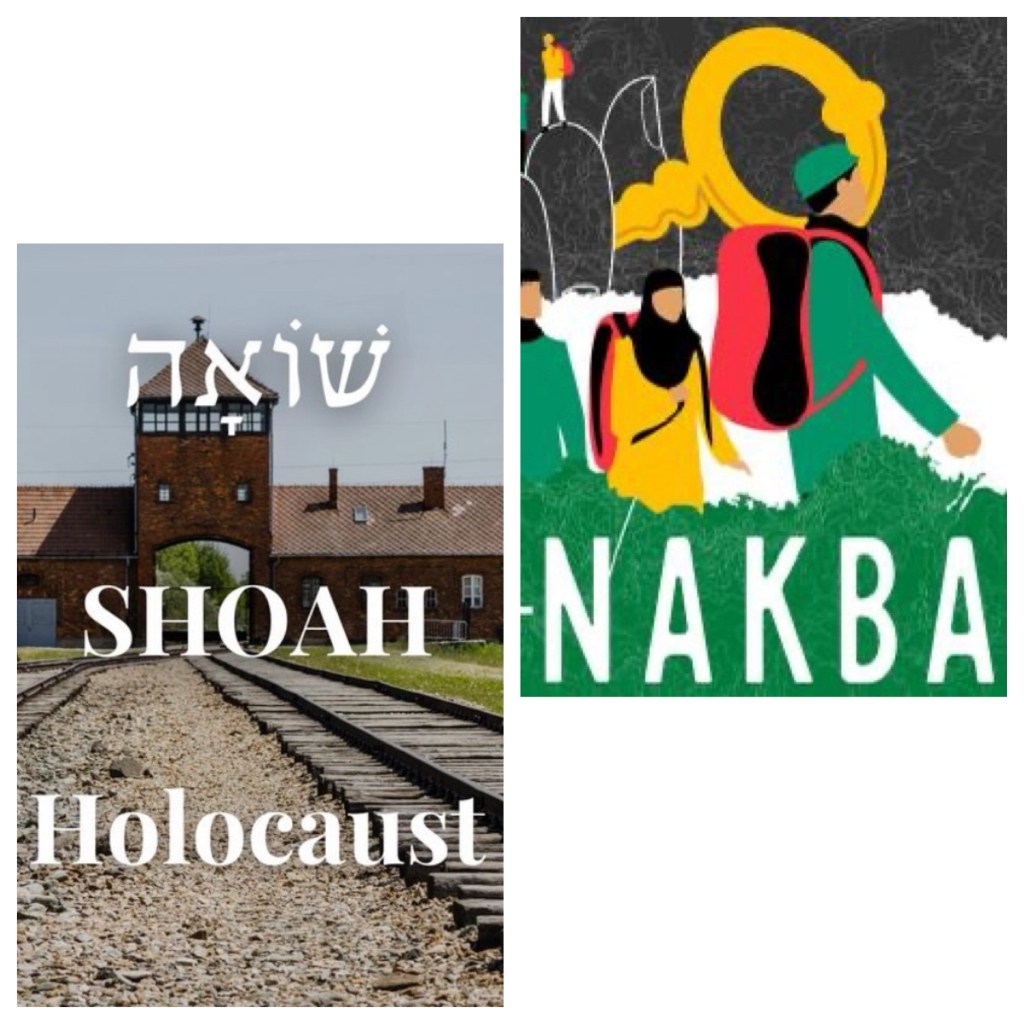

The history of “the peace” in this region over the past 50 years does not give grounds for hope. The establishment of Israel in 1948, as important and necessary as that was after the horrors of the Shoah (a Hebrew word meaning “desolation, sudden destruction, catastrophe”), caused the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of inhabitants of that area, in a catastrophe called by Palestinians the Nakbah (an Arabic word which also means “catastrophe”).

The Camp David Accords (1978) ultimately led to an agreement in which Israel agreed to “resolve the Palestinian question” and permit Palestinian self-governance in the West Bank and Gaza within five years. It never happened.

The Oslo Accords (1993) included a pledge to end hostilities, and the second Accords (1995) provided that Israel would accept Palestinian claims to national sovereignty. As an interim measure, a Palestinian Authority was established, to govern designated areas (see the map) in a phased process leading towards Palestinian self-determination. The Palestine Authority still exists today, and the goal of the Accords has never been reached.

See https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/9/13/what-were-oslo-accords-israel-palestinians

Indeed, from 1993 onwards, Israel increased its building of settlements in the West Bank, leaving that area utterly fragmented between Israeli and Palestinian areas—a process deemed illegal under international law. Families who had lived on their historic lands were expelled so that new Israeli settlements could be built. It’s been an utterly unjust process.

When PLO leader Yasser Arafat gave up the right for Palestinian refugees to return to their historic lands which Jewish settlers had seized from them in 1948 when Israel was created, many Palestinians became disenchanted with him. The ground was fertile for dissent and revolt; Hamas emerged out of this situation as the leading organisation advocating for—and acting to gain—a Palestinian right to return. Peace was never possible while such an ideology was the key driving force.

Chris Hedges, an American journalist, author, and commentator (and also an ordained Presbyterian minister, as of 2014) writes that the current “peace” is simply “a commercial break … a moment when the condemned man is allowed to smoke a cigarette before being gunned down in a fusillade of bullets”. He foresees the crumbling of the current ceasefire, on the basis of the history of these recent decades.

“Once Israeli hostages are released, the genocide will continue”, he writes. “A pause in the genocide is the best we can anticipate. Israel is on the cusp of emptying Gaza, which has been all but obliterated under two years of relentless bombing. It is not about to be stopped. This is the culmination of the Zionist dream.”

He notes the staggeringly obscene amount of military aid that the USA has given Israel, and observes that the US “will not shut down its pipeline, the only tool that might halt the genocide”. He then goes on to argue that “of the myriads of peace plans over the decades, the current one is the least serious”. He details all the flaws and inadequacies in the much-trumpeted 20-point “peace plan” that has been advocated recently and claims that “there will be no peace in Gaza; only the temporary absence of war”.

Hedges notes that this “peace plan” fails to mention Palestinians’ right to self-determination; it ignores the advice of the International Court of Justice that Israeli settlements are illegal; it places no brakes on Israel’s continuing military power; it does not provide for Israel to provide anything in the way of reparations for Gaza, the area which it has mercilessly bombed; and many provisions are vague to the point of being unenforceable. You can read his scathing analysis at https://chrishedges.substack.com/p/trumps-sham-peace-plan?

Eric Tlozek, the ABC’s Middle East correspondent, observes that “Israel gets to keep troops in Gaza instead of having to withdraw, but that only signifies that the key issues in this conflict — disarmament, security, governance — are far from being resolved”. What will change once the thousands of displaced Gazans return?

He continues, “Hamas still refuses to disarm and remains in control of large parts of the [Gaza] strip. The US may claim the war is over, but Israel’s defence minister has already flagged plans to attack Hamas, and Israeli fire and air strikes continue in Gaza. The violence has not ended, it has only decreased in intensity.” Tlozek’s pessimism is, nevertheless grounded in reality.

See https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-10-15/donald-trump-should-not-be-thanked-for-the-gaza-ceasefire/

Will the current “peace” last? How long will it last? How long before the genocide of Palestinians resumes and continues to its inexorable end? As a person of faith, I can join with people of faith around the globe, to pray and to hope. As a citizen of the world in 2025, however, I think that, sadly, we must temper this with realism about the situation and the prospects of an enduring peace.

*****

See my other, earlier, ruminations at