“A hot wind comes from me out of the bare heights in the desert toward my poor people, not to winnow or cleanse— a wind too strong for that. Now it is I who speak in judgment against them.” (Jer 4:11–12)

We’ve been following the words of Jeremiah over the last three weeks. He has had some very stern messages to deliver. Perhaps this helps us to see the origins of the term “Jeremiad”. The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms defines it as “either a prolonged lamentation or a prophetic warning against the evil habits of a nation, foretelling disaster”. The second sense (a prophetic warning) comes directly from the way that the prophet Jeremiah spoke about, and to, the people of Israel in his time.

Jeremiah was, indeed, a voice of doom and gloom. At his calling, the Lord God informed him, “I will utter my judgments against them, for all their wickedness in forsaking me; they have made offerings to other gods, and worshiped the works of their own hands”. He then admonished the young Jeremiah, telling him to “gird up your loins; stand up and tell them everything that I command you”, before putting the very fear of God into him with the warning, “do not break down before them, or I will break you before them” (Jer 1:16–17). That’s stern stuff!

But is this going too far? I think today we would want to call to account the speaker of these words, to remind them not to abuse the power that they have in this relationship, and to be mindful of the vulnerability of the young person to whom they are speaking! (A friend who worked for the then Department of Community Services said years ago that Yahweh would these days be notified to the department if he spoke and acted in this way!)

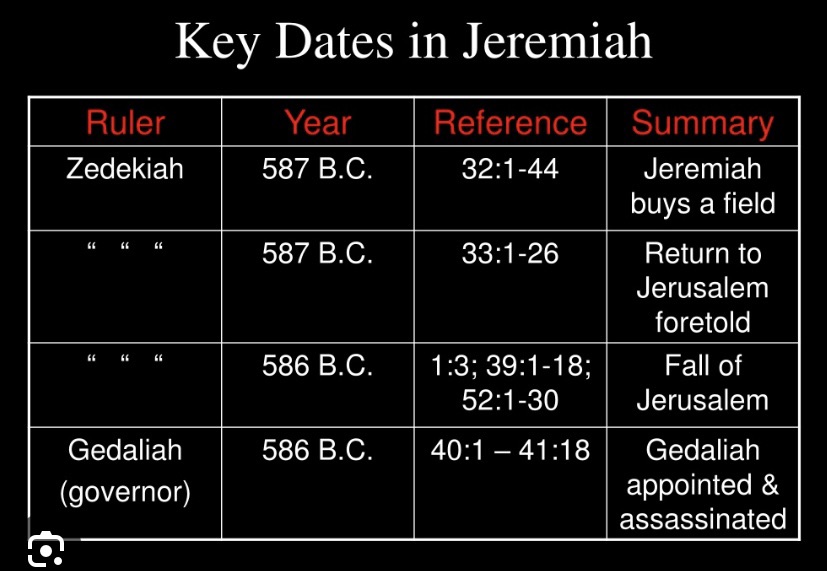

So Jeremiah remains faithful to his call, through all the challenges and difficulties this brought him. For four decades he is relentless is calling the people of his day to account for their sins: “the house of Israel and the house of Judah have broken the covenant that I made with their ancestors” (11:10); “we have sinned against the Lord our God, we and our ancestors, from our youth even to this day; and we have not obeyed the voice of the Lord our God” (3:25).

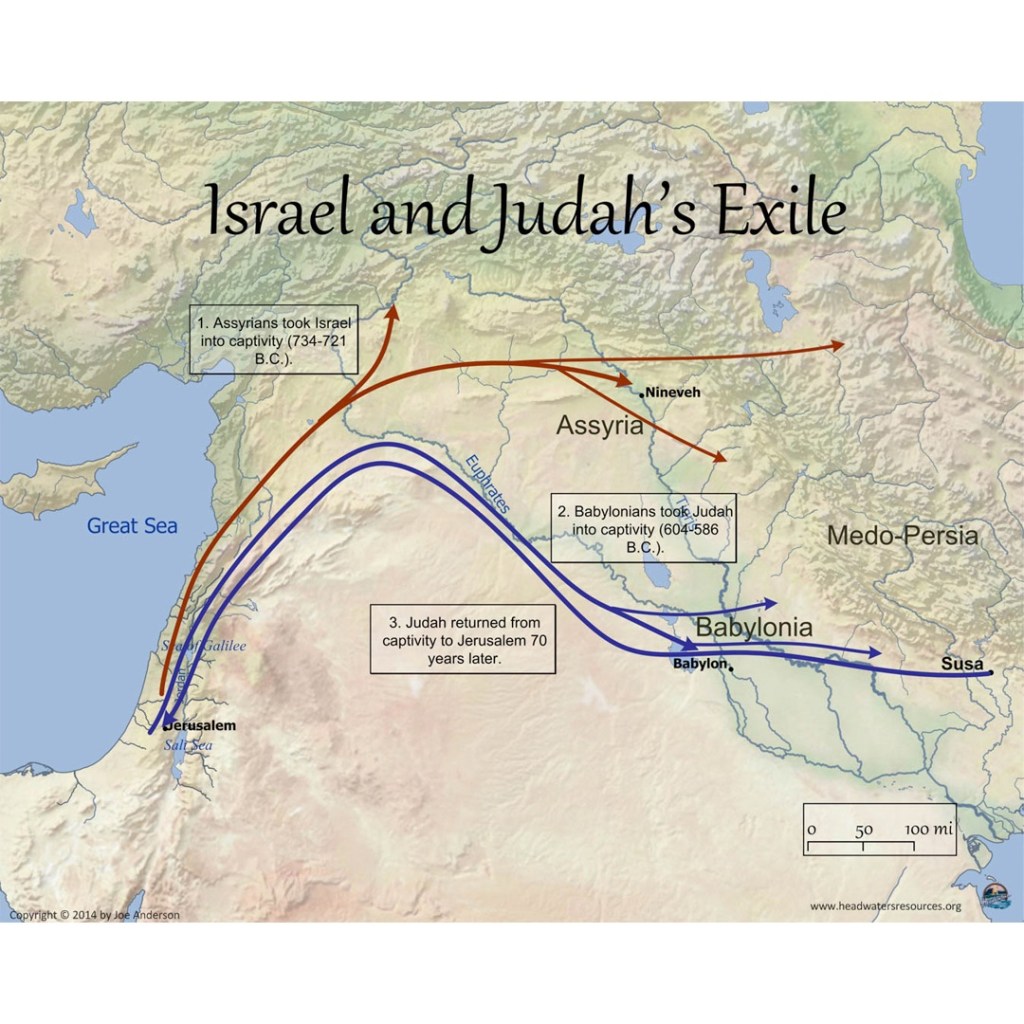

In the passage set before us by the lectionary for this coming Sunday, the prophet reports God’s anguish about Israel: “my people are foolish, they do not know me; they are stupid children, they have no understanding; they are skilled in doing evil, but do not know how to do good” (4:22). In despair, God decides to use a foreign power to bring Israel to their senses. He tells the prophet, “I am now making my words in your mouth a fire, and this people wood, and the fire shall devour them. I am going to bring upon you a nation from far away, O house of Israel, says the Lord” (5:14–15). Thus Jeremiah foretells the invasion of the Babylonians (see 2 Ki 25).

Jeremiah senses that God has fixed the course to be taken: “they have taught their tongues to speak lies; they commit iniquity and are too weary to repent. Oppression upon oppression, deceit upon deceit! They refuse to know me, says the Lord … Shall I not punish them for these things? says the Lord; and shall I not bring retribution on a nation such as this?” (9:5–6, 9). National disgrace awaits them, as they submit to a foreign power.

Eventually, from his exile in Egypt, and as others from his nation are taken north into exile by the invading Babylonians, Jeremiah tells the Israelites, “It is because you burned offerings, and because you sinned against the Lord and did not obey the voice of the Lord or walk in his law and in his statutes and in his decrees, that this disaster has befallen you, as is still evident today” (44:23). He has been resolute in his condemnation of the sinful people. He is now, sadly, vindicated. And so God decrees, “I am going to watch over them for harm and not for good; all the people of Judah who are in the land of Egypt shall perish by the sword and by famine, until not one is left” (44:27).

I must confess that it seems quite easy, at the moment, to slip into a simplistic interpretive pattern and apply these words—spoken long again against a sinful nation—to the very nation, today, who still bears the same name as those ancient people: Israel. The sins of the modern nation of Israel are manifold. Established as a refuge for a persecuted people, the nation has turned persecutor. Given land in recognition of the way they had been disposed and dispersed, the landholders sought more and more land, building settlements on Palestinian land, erecting a strong, impenetrable wall to keep “them” from “us”.

In a series of battles, they have waged war to ensure their safety and security. Besieged by leaders of organisations arrayed against them, they have continued to shoot, bomb, and destabilise such “terrorist” groups. Yet what is happening in Gaza today is no longer able to be distinguished from genocide—the very same genocidal actions that the Jewish people experienced almost a century ago. The sins of the nation appear (at least to me) to be clear, persistent, and utterly repugnant. Jeremiah’s words to ancient Israel—“I am determined to bring disaster on you, to bring all Judah to an end” (44:11) could well be the words of God to the modern nation of Israel.

Can we simply apply to condemnation of Jeremiah to modern Israel? It’s tempting; but it’s not responsible interpretation. And it leaves open the door to the accusation—repeated often, now—that this is antisemitic. I don’t believe it is antisemitic, because such criticisms are directed against the policies and practices of the modern nation-state of Israel, and what they result in, and not against all Jews everywhere, simply for being Jewish. So we need to steer clear of this kind of simplistic equation. The criticisms are political and pragmatic, not based on religion or ethnicity.

For my analysis of the current situation involving Israel, Hamas, Gaza, and Palestine, see

and

All of this is in the book of Jeremiah: denunciation after denunciation of the people, warnings of divine punishment, and oracles portending imminent exile and absolute destruction. We can’t get away from that.

However: the passage that the lectionary offers for this coming Sunday raises the stakes even higher. In this passage (Jer 4:11–12, 22–28), the wrath of God is directed not just to Israel, but to all creation. The looming catastrophe is not just national; it is global, cosmic in its scope.

To be sure, the passage reports God’s anguish about Israel, as we have noted: “my people are foolish, they do not know me; they are stupid children, they have no understanding; they are skilled in doing evil, but do not know how to do good” (4:22).

But then comes a most remarkable sequence of sentences, in which the whole of creation seems to be in view. “I looked on the earth, and lo, it was waste and void; and to the heavens, and they had no light”, God is saying. “I looked on the mountains, and lo, they were quaking, and all the hills moved to and fro. I looked, and lo, there was no one at all, and all the birds of the air had fled. I looked, and lo, the fruitful land was a desert, and all its cities were laid in ruins before the Lord, before his fierce anger” (4:23–26).

Writing on this Jeremiah passage in With Love to the World, the Rev Dr Anthony Rees, Associate Professor of Old Testament in the School of Theology, Charles Sturt University, notes: “This is a remarkably evocative passage. It begins with a hot wind, a symbol of judgement (as in Jonah 4). It moves quickly to a promise of destruction from the North (Dan and Ephraim); it almost seems that God is cheering on those who would do Judah harm.”

But there is more than just evocative poetry here. It seems to me that the words of Jeremiah might be describing the end result of a process that is happening in our own time. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, and continuing apace into the 21st century, the damage that human beings have been causing to the planet has been increasing with noticeable impacts seen in so many areas: global warming, more intense extreme weather events, more frequent extreme weather events, the diminishing of the ice caps at the poles of the earth, the warming of the oceans’ temperature, rising sea levels impacting particularly islands in the Pacific, the bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef, and so many more things that can be attributed to human-generated climate change.

In our own household, in just the past five years, we have seen a searing bushfire come within a few kilometres of our suburb, and then a massive downpour lead to rising floodwaters that reached the other side of the road on which we live. Climate change is real, and close. We are well on track, as many scientists are saying, to see a planet with a radically altered ecosystem.

Gordon, ACT, January 2020 (top),

during the severe bushfire in the ACT;

Dungog, NSW, May 2025 (bottom),

during the east coast flooding

Anthony Rees continues his reflections on Jer 4: “Judah is destroyed, the people and land laid waste on account of childish stupidity and ignorance. A remarkable image is then seen: the earth is described as waste and void, the very same description given of the earth in Gen 1:2 before God’s creative activity begins.”

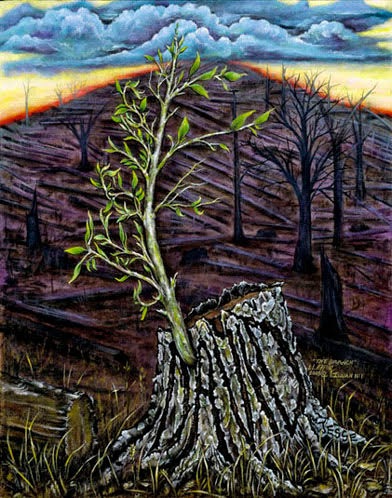

The passage in Jeremiah has God narrating his view of the systematic undoing of his work as the Creator, as that has been set out in the narratives of Gen 1 and Gen 2, and in the poetry of Psalms 8, 19, 65, 104, and 148. God sees that the earth was once again “waste and void” (Jer 4:23a), as it was in the beginning (Gen 1:2). All that the landscape showed was a ravaged wilderness, for no longer did the earth bring forth vegetation: “plants yielding seed of every kind, and trees of every kind bearing fruit with the seed in it” (Gen 1:12; 2:8–9; and see Ps 65:11–13; 104:14–15, 27 –28). Rather, what God sees is that “the fruitful land was a desert, and all its cities were laid in ruins” (Jer 4:26).

In the heavens there is no light (Jer 4:23b), thus undoing God’s early creative work (Gen 1:3, “let there be light”; and Ps 8:3; 19:4b—6; 148:3). Hills and mountains were shaking (Jer 4:24); the stability they provided, the unshakeable foundation of the earth, has been undone (Ps 65:6; 104:5, 8; 148:9). All the birds have fled (Jer 4:25), undoing the work of God reported at Gen 1:21–22 (and see Ps 8:8; 104:12; 148:10b).

Anthony Rees notes, “Jeremiah looks to the heavens and the light is gone. God’s creative work has been undone on account of human failure. And again, human failure has consequences that go beyond our species: mountains sway, birds flee, arable land is turned to desert. What good news is there to be found here? What image of hope?”

The relevance for today of Jeremiah’s poetic “vision” that undoes the vision of creation expressed long ago by priests and poets is striking. And his perception that it is human sinfulness that is at the root of this is noteable. We know what we need to do to slow the rate of change, so that the climate remains within an inhabitable range. We know what we need to do to stop pumping gases into the air that are changing the way the planet works. We know what changes we need to make to our way of living—a whole host of changes, large and small—but we lack the will to do so. Our national policies continue to favour the industries that contribute most to the degradation of our environment. Our daily practices show minimal change, if that, in so many households.

Anthony Rees concludes, “Perhaps we might best read this text as a warning, and commit ourselves to working in ways that maintain relationship with God, our neigbours, and the rest of the created order.” It is certainly a timely word, given our critical situation. How do you respond to Jeremiah’s mournful poetry? What changes can you make? What lobbying can you undertake? What advocacy can you commit to do? Are we always going to be condemned to be, like ancient Israel, those who “are skilled in doing evil, but do not know how to do good”?