Two weeks ago, the lectionary directed us to turn off the road we were following through the story of “the beginning of the good news of Jesus, Messiah” (which we know as the Gospel of Mark), and spend five weeks with “the book of signs”, which contains just some of “the many things that Jesus did” (which we know as the Gospel of John).

This detour came just at the point when we were going to read the story of when Jesus took “five loaves and two fish, looked up to heaven, and blessed and broke the loaves, and gave them to his disciples to set before the people; and he divided the two fish among them all … [and] those who had eaten the loaves numbered five thousand men” (Mark 6:30–44). The wording is strongly evocative of the Eucharistic words that Mark later reports: “he took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to them …” (Mark 14:22).

Instead, two Sundays ago we read or heard the account that John gives us, with a less-eucharistic flavour, when Jesus “took the loaves, and when he had given thanks, he distributed them to those who were seated; so also the fish, as much as they wanted” (John 6:1–13); and from that passage, we are then guided over the following four Sundays to follow the extensive discourse that Jesus gives to a crowd that “went to Capernaum looking for Jesus” (John 6:25–71).

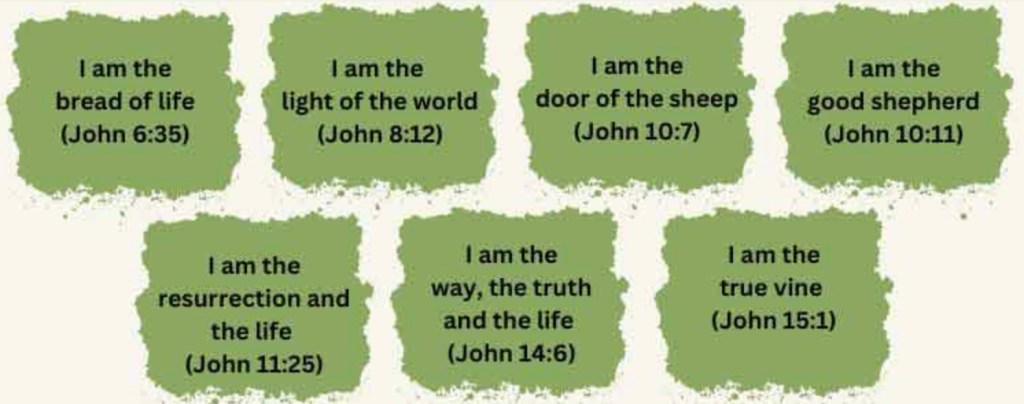

Last Sunday, John 6:24–35 was the passage that the lectionary proposed as the Gospel reading. This passage ends with the first I AM declaration by Jesus, “I am the bread of life” (6:35).

After hearing that, on the next Sunday (this coming Sunday) we will read or hear the next section of that discourse, dealing with an elaborated exposition of that “bread of life” (6:35–51). That is to be followed by an account of the disputes that this teaching generated with the Judaean authorities (6:51–58), and then the final section of the discourse where Jesus then has to deal with dissent from his own disciples (6:56–69).

I have already offered comments on those two earlier sections, and plan to continue to trace the words and interactions of Jesus from this long chapter in the coming weeks. For today, we focus on the way that Jesus expands and develops his theme of “the living bread which came down from heaven” (6:35–51). And interestingly, after having eschewed a direct eucharistic allusion in the miracle reported earlier, here the Johannine Jesus takes us step-by-step towards a strongly eucharistic understanding. (More on that in coming weeks.)

A key observation that can assist us in understanding this lengthy discourse is that it has the nature of a Jewish midrashic discussion. The Jewish Virtual Library notes that there are two main types of midrash, and defines it as follows: “Midrash aggada derive the sermonic implications from the biblical text; Midrash halakha derive laws from it.”

The article continues: “When people use the word midrash, they usually mean those of the sermonic kind. Because the rabbis believed that every word in the Torah is from God, no words were regarded as superfluous. When they came upon a word or expression that seemed superfluous, they sought to understand what new idea or nuance the Bible wished to convey by using it.” That is how I am understanding the relevance of this section of the discourse in John 6.

See https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/halakha-aggadata-midrash#google_vignette

My Jewish Learning defines midrash as “an interpretive act, seeking the answers to religious questions (both practical and theological) by plumbing the meaning of the words of the Torah. Midrash responds to contemporary problems and crafts new stories, making connections between new Jewish realities and the unchanging biblical text.”

See https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/midrash-101/

That would indicate that the words of Jesus, in John 6 (as, indeed, elsewhere in the Gospel) were being remembered and retold, expanded and developed, in light of the hopes, concerns, and needs of the community within which this Gospel came into being. In other words, whilst we do not have an accurate historical reporting of “what Jesus actually said”, we do have words which give us a pathway into understanding how at least this group of followers of Jesus understood him, and how they lived in response.

It seems to me that applying a Jewish understanding of how biblical texts are appropriated and understood, through midrash, helps to explain what is happening in John 6. Although it seems repetitive to us moderns, the discourse is actually probing the possibilities and exploring the options in understanding the scripture text that was provided to Jesus by the crowd around him.

Earlier in the chapter, a series of questions have been put to Jesus, moving to a key matter, when the crowd asks: “what sign are you going to give us? … what work are you performing?” (v.30). They continue by quoting scripture (v.31)—a move that is fundamental for the nature of what follows.

By quoting scripture, the crowd gives Jesus his “text” for the teaching that follows. And, of course, as they are Jews, and as Jesus was a Jew, the argument is developed by means of a typical midrashic “playing with the text” in the words that follow. More than that, when we look for the text that the crowd speaks, we find it is a compilation text—something that draws on the post-exilic narrative of the manna from heaven (Exod 16:4 and 15), a poetic retelling of this scene (Psalm 78:24), and an even later Hellenistic-era reporting of this incident (Wisdom of Solomon 16:20).

The fact that we do not have a precise quotation of the text “as we know it” should alert us to the fluidity that was commonplace in the ancient world, when texts were referred to. My own teacher, the late Dr. Robert Maddox (in an unpublished paper entitled “The Use of the Old Testament in John’s Gospel”) put it very clearly:

“The freedom of wording of John’s quotations and allusions is due not to ignorance nor to the nature of the texts he used, but to the fact that he had steeped himself in the Scriptures, as Jesus had before him; and the Biblical text was no longer something external to be reached for to bolster an argument, but something which had become a part of the author’s mind and heart.”

Dr Maddox offers this concise summation of how the author operated: “He treats the Biblical text not with the deference of polite respect but with the freedom of intimate familiarity.”

So, what follows here is a typical Jewish midrash—a use of the text in a somewhat fluid and flexible way that develops and expands a theme. How does Jesus do this? We can be helped by the work of Scandinavian scholar Peder Borgen. He offers a detailed (book-length) analysis of this discourse in the context of the practices and techniques found in rabbinic literature. The book is entitled Bread from Heaven: An Exegetical Study of the Concept of Manna in the Gospel of John and the Writings of Philo (NovTSup 10, 1965).

Borgen compares the midrash undertaken by the Johannine Jesus with midrahim on the same theme found in a third century rabbinic work, the Mekhilta on Exodus 16:15, as well as in a tractate written about a century before John’s Gospel by the Alexandrian scholar Philo, with the title That the Worse is Wont to Attack the Better (Quod det. potior.). (And yes: in preparing to teach John’s Gospel at tertiary level some 25 years ago, I worked carefully through the detailed argument that Borgen has provided!)

Borgen proposes two sections to this midrash: what he calls “a miniature elaboration” in three parts (vv.31–35), followed by “a more detailed elaboration” in four parts (vv.41–51). The first section begins with the scripture citation: “he gave them bread from heaven to eat” (v.31b) and concludes within the full statement of the theme by Jesus: “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty” (v.35).

The second section recapitulates theme, in words attributed to “the Judaeans”, repeating (and expanding) the earlier words of Jesus: “he said, “I am the bread that came down from heaven” (v.41). In between, Jesus engages in a (typical) excursus, discussing “the will of my Father”, which is what he is charged with carrying out (vv.36–40). Belief (v.36) will lead to eternal life (v.40)—a central Johannine motif (see John 3:14–16, 36; 5:24–29; 6:68–69; 11:25–27; 14:6–7; 17:1–3; 20:31).

In the “miniature elaboration” (vv.31–35), after the crowd has stated the key issue in their scripture citation (v.31), Jesus offers an interpretation of this scripture by means of a classic rabbinic-style contrast statement; it is “not Moses … but my Father in heaven” who provided the bread (v.32).

The allusion back to the earlier programmatic declaration in the Johannine prologue is clear: “the law indeed was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ” (1:17). In what follows, Jesus will seek to place himself, as “the bread of life”, in the position occupied by “the Father” in that earlier statement.

So at this point, he pivots from speaking about the bread that God gave from heaven, to speaking about “the true bread from heaven”, himself. An explanation, introduced by the little word gar (“for”), is that Jesus is the bread which “gives life to the world” (v.33). Then, instead of a question, the crowd puts a request to Jesus; “Sir, give us this bread always” (v.34). Which means that Jesus can now make very clear what his thesis is: “I am the bread of life” (v.35).

After the excursus about “doing the will of my Father” (6:40; a matter found also at 4:34; 7:17; 14:13), it is “the Judaeans” who bring Jesus back to the topic at hand. In the “more detailed elaboration” that follows, we find that the restatement of the theme is put onto their lips, as they complain about what he has said (6:41). The use of the verb Ἐγόγγυζον is a deliberate reference to “the murmuring tradition” in the Pentateuch, when the Israelites complained about the hardships of the desert (Exod 15:24; 16:2, 7; 17:3; Num 11:1–2; 14:2–4; 27, 29, 36).

In the objection raised these critics question the authority of Jesus to speak in this way: “Is not this Jesus son of Joseph?” (v.42a), followed by a further repetition of what Jesus is declaring: “how can he now say, ‘I have come down from heaven’?” (v.42b). The placing of the claim made by Jesus on the lips of his opponents—not once, but twice—is a delicious irony!

There follows an answer to this objection, given at some length, by Jesus (vv.43–48). In so doing, Jesus draws himself on another scripture passage (Isa 54:13, at John 6:45). This is absolutely typical of the rabbinic style of midrashic argumentation, in which (as we have seen) an explanation of one text is provided by reference to another scripture text , related by means of a key word or idea.

What Jesus says to them also draws on the typical Joannine motif of Jesus as the one who has “come down from heaven” (v.38; see also 3:13, 27, 31; 12:28; 17:1–5). Another one of my teachers, Professor Wayne Meeks of Yale University, picked up n on the importance of this motif in an article he published just over 50 years ago.

Meeks notes that the claims made about Jesus in the fourth Gospel function as reinforcements of the sectarian identity of the community. As this community had come into existence because of the claims that it had made about Jesus, so the reinforcement of the life of the new community took place, to a large degree, through the strengthening and refining of its initial claim concerning Jesus. What is said about Jesus can also be said about his followers. So what the Johannine Jesus is doing in this long discourse is not simply clarifying his identity; these words provide a reinforcement of how the members of the later community of believers saw themselves in the world. (Again, we will come back to this in a later blog.)

Joh has Jesus make one of his typically exclusivist claims at this point: “not that anyone has seen the Father except the one who is from God” (v.46). Here, Jesus stakes out his claim: he is The Teacher, The Revealer, The One who has seen God and who conveys that truth to those who follow him. This is how “eternal life” is gained: through access to this knowledge, passed on in what Jesus reveals.

So Jesus returns to the main theme with his repeated assertion, “I am the bread of life” (v.48, repeating v.35), and then continues with an expositional development in the following verses. Again he compares “your ancestors” who, although they “ate the manna in the wilderness”, nevertheless died (v.49) with his role, as “the bread that came down from heaven”, which means that anyone eating it will not die (v.50). We are edging into the centre of eucharistic theology at this point, with talk of eating “the bread from heaven”, that is, Jesus. (More on this in a subsequent blog.)

Verse 51 restates what has just been declared: first, the primary affirmation about Jesus: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven”; followed by the consequence for those who believe in him: “whoever eats of this bread will live forever”. It seems redundant to us, but in the midrashic style it is important to synthesize and summarise in this manner.

There is a further step that Jesus takes in what he says at the end of v.51. This also is typical of midrashic style texts; summarise but immediately extend the argument. And the extension that Jesus gives here opens u0 a new issue—one which will be the focus in the following verses, which the lectionary reserves for us to read and hear on the Sunday after this coming Sunday. “The bread that I will give for the life of the world”, Jesus declares, “is my flesh” (v.51c). And so a new matter requires attention … which we will explore in the blog for the Sunday after this coming Sunday.

See also

and on the whole sequence of this chapter