Each year, on the fourth Sunday of the season of Easter, the Revised Common Lectionary provides a section of John 10 as the Gospel reading for the Sunday. That chapter is where Jesus teaches about his role as “the good shepherd” who lays down his life for the sheep. The chapter is divided over the three years: 10:1–10 in Year A, then 10:11–18 in Year B, and 10:22–30 in the current year, Year C. For this reason, this particular Sunday is sometimes called the Good Shepherd Sunday.

The section offered in Year A concludes with the classic claim of Jesus, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly” (10:10). The passage set for Year B begins with the famous affirmation, “I am the good shepherd; the good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep” (10:14-15).

Both passages develop the image of Jesus as the shepherd of the sheep, in intimate relationship with the sheep; the shepherd knows his own (10:15), calls them by name (10:3), shows them the way of salvation (10:9), and lays down his life for the sheep (10:11, 15, 17–18).

The third section from John 10, offered in Year C, is set at a different time. The earlier sections (10:1–10, 11–18) had followed on from the story of the man born blind (9:1–41), which itself has emerged out of the conflicts between Jesus and Jewish authorities (7:10—8:59), reported as taking place in Jerusalem during the Festival of Booths (7:2). That sequence of conflicts had culminated with the Jewish authorities picking up stones to throw at Jesus (8:59).

The second moment when Jewish authorities in Jerusalem prepare to stone Jesus (10:31) is at the end of the later part of John 10, in this Sunday’s reading (10:22–31). This section, still in Jerusalem, is set during the Festival of the Dedication (10:22), some time later than the earlier Festival of Booths (7:2). It includes a further statement about the shepherd: “my sheep hear my voice. I know them, and they follow me. I give them eternal life, and they will never perish. No one will snatch them out of my hand.” (10:27–28).

However, the focus on this section is less on the shepherd and the sheep, and more on Jesus and his relationship with the Father. Indeed, the lectionary ends the section before the climax of the conflict, when Jewish authorities pick up stones (10:31). Rather, the final verse places the emphasis in quite another direction: “The Father and I are one” (10:30). This is one of a number of key verses in this Gospel where important claims about Jesus are placed onto his lips.

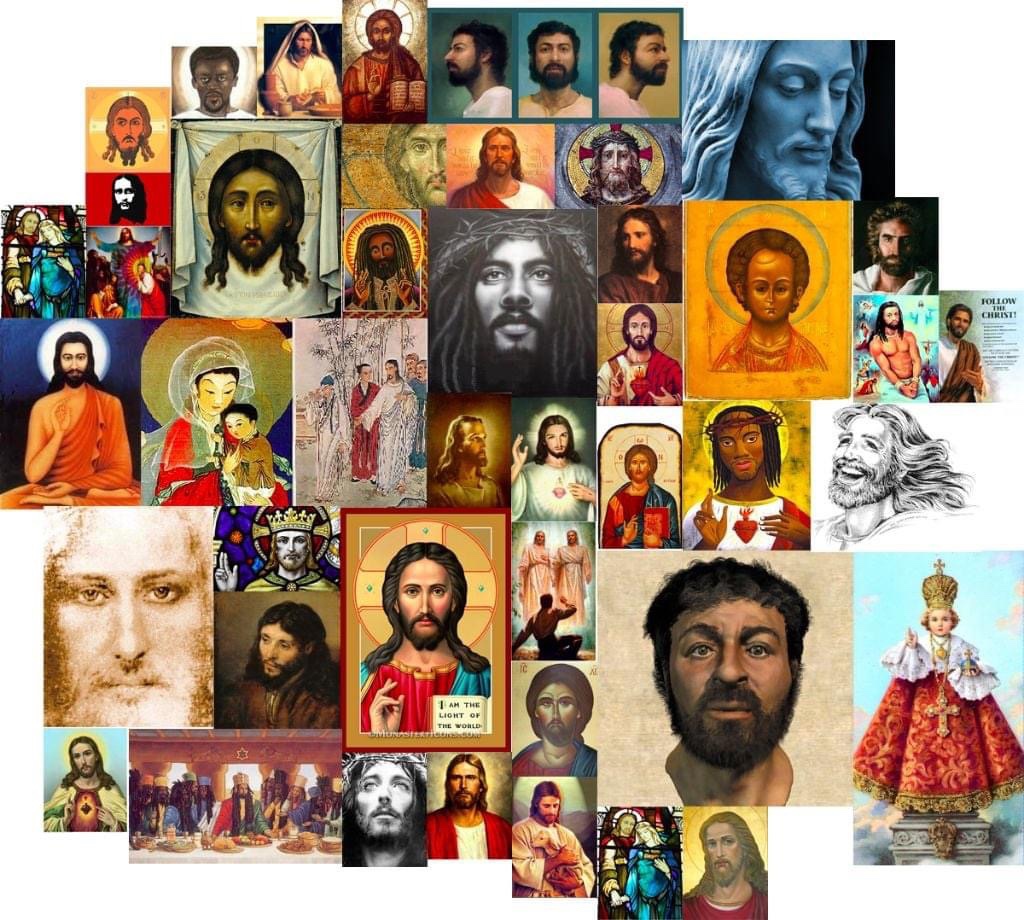

Wayne Meeks (in his classic article, “The Man from Heaven in Johannine Sectarianism”, JBL 91 (1972) 44–72) notes that the claims made about Jesus in the fourth Gospel function as reinforcements of the sectarian identity of the community. As this community had come into existence because of the claims that it had made about Jesus, so the reinforcement of the life of the new community took place, to a large degree, through the strengthening and refining of its initial claim concerning Jesus.

Claims made about Jesus, the Messiah (Christ) thus function as markers of the emerging self–identity of the new community, over against the inadequate understandings of Jesus which continue to be held in the old community (the synagogue), still under the sway of the Pharisees. This function can be seen in a number of other terms which are used of Jesus in the Gospel according to John.

As Meeks notes, one of the most common self–designations of the Johannine Jesus is that he is “the one sent from God”. This is another phrase which is unique to the Gospel according to John; the nearest Synoptic equivalent is found in the parable of the vineyard (Mark 12:1–8 and parallels).

The phrase may well originate in the Jewish notion of the shaliach, or messenger (for the wordplay involved in this word, see 9:7). A recognisable form of this phrase occurs 42 times in this Gospel (for instance, at 1:33; 3:34; 4:34; 10:36; 11:42; 20:21).

This claim consolidates the link between Jesus and God, binding his mission to the mission of the Father, and making a claim for Jesus which transcends the kind of claim which could be made of a chosen messenger figure.

Jesus is clear that he belongs to the world “above”, the heavenly realm, where— according to the worldview of the time—God is to be found. He declares, “I am from above…I am not of this world” (8:23); this is in contrast to the Pharisees, who are “from below” and “of this world”.

As king, he informs Pilate, he rules over a kingdom which is “not from this world” (18:36). The distinction between Jesus and the earthly authorities of the day is firmly held; Jesus belongs with God. He comes to earth in order to bring into effect the judgement of God over “the ruler of this world” (12:30–33).

Another characteristic which dominates the Christology of this Gospel is the Father-Son relationship (3:35–36; 5:19–23, 26; 6:37–40; 8:34–38; 10:32–38; 14:8–13; 17:1–5). At the conclusion of the Prologue, the importance of this relationship is established: “it is God the only Son, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known” (1:18).

In one of his disputes with the Jewish authorities, Jesus declares that he does his works “so that you may know and understand that the Father is in me, and I am in the Father” (10:38). This mutual interrelationship is brought to the pinnacle of its development in the lengthy prayer of chapter 17. The purpose of describing this relationship in this way is to strengthen the claims made for Jesus, to validate him as authoritative, in the context of debates with the Jewish authorities.

Finally, Jesus is perceived as being “equal with God” (5:18). At the narrative level, this is a polemical view of Jesus, attributed to the Jews. However, the author of the Gospel clearly wants the readers to agree with the claim. This is supported by further comments such as: it is clearly evident that he is the Messiah, for he is “doing the works of God” (10:24–25); he is one with the Father (10:30); he is “making himself a god” (10:33); “he has claimed to be the Son of God” (19:7); and he is acclaimed as “Lord and God” (20:28).

This is the strongest claim made about Jesus; it lifts him above the realm of human debate and, as a consequence, it also lifts the claims made by his disciples, in his name, above that human realm. By this means, the community of his followers lay claim to a dominant, privileged position, vis–a–vis the Jewish authorities.

The Christology which is proclaimed in the written Gospel has thus been developed and refined in the controversies and disputes of the community over the preceding decades, as each of these markers of the identity of Jesus were debated amongst Jewish groups, and as the community formed around Jesus differentiated itself in various ways from the dominant stream of Pharisaic Judaism (especially in the period after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE).

Later Christian theology developed the doctrine of the Trinity, in which God, Jesus and the Spirit relate to one another as equals. Whilst the Gospel of John provides biblical warrant for the equality of Father and Son, the role of the Spirit is less prominent. Jesus is endowed with the Spirit at his baptism (1:32– 33) and gives the Spirit to others through the words he speaks (3:34).

However, the Spirit is clearly subordinated to the Son in this Gospel. It is not until after Jesus is glorified that the Spirit is given (7:39; 20:22). The role of the Spirit is to be the Advocate of the Son (14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7), sent by the Son to testify on his behalf (15:26) and to represent what has already been spoken by Jesus (14:26; 16:13–15). As the Son testifies to the truth (1:14, 17; 8:32, 45–46; 14:6; 18:37), so the Spirit is “the spirit of truth” (14:17; 15:26; 16:13).

So the long, extended scene in Jerusalem ends as “they tried to arrest him again, but he escaped from their hands” (10:39). Jesus moves “across the Jordan to the place where John had been baptizing earlier” (10:40), where many expressed their belief in him. The next, more intense, conflict still lay ahead of Jesus—by raising Lazarus from the dead (11:38–44), Jesus placed himself firmly in the sights of the Jerusalem leadership; his own death was brought firmly into view (11:45–53; 12:10–11).