“Then Joshua gathered all the tribes of Israel to Shechem, and summoned the elders, the heads, the judges, and the officers of Israel; and they presented themselves before God … so Joshua made a covenant with the people that day, and made statutes and ordinances for them at Shechem” (Josh 24:1, 25).

For the last two weeks, we have been considering the matter of the land promised to Israel and claimed by them under Joshua, as we heard first Deut 34 and then Josh 3. This week, as the lectionary presents us with a second passage from the book of Joshua (Josh 24:1–3a,14–25), our attention is turned to the covenant, the formalising of the relationship between the Lord God and the people of Israel.

The covenant that was formally ratified on that day had already been made with the people. During their wanderings in the wilderness, Moses “went up to God” on Mount Sinai, where the covenant was offered to Moses by God, and the people accepted the offer (Exod 19:1–8). The covenant was sealed in a formal ceremony in which “the blood of the covenant” was splashed on the altar and the people (Exod 24:1–8).

That covenant stood on the foundation of a series of covenants that had already been offered to people—initially to Noah, and to all living creatures (Gen 9), before it was subsequently renewed (and reshaped) by being offered to Abraham (Gen 15, 17). That same covenant was then renewed with Isaac (Gen 17) and then with Jacob (Israel) (Gen 35), before being extended to Moses and the whole people (Exod 19).

It is this sequence which is celebrated by the psalmist: “The Lord our God … is mindful of his covenant forever, of the word that he commanded, for a thousand generations, the covenant that he made with Abraham, his sworn promise to Isaac, which he confirmed to Jacob as a statute, to Israel as an everlasting covenant” (Ps 105:7–10).

And it is this sequence of events which is remembered in the narrative of Joshua 24. It begins by recalling when “your ancestors—Terah and his sons Abraham and Nahor—lived beyond the Euphrates and served other gods” (Josh 24:2), a time reported in Gen 11:26–32. Then follows the gifting of land and descendants to Abraham (Josh 24:3), recalling the promise of Gen 12:1–3 and the story told in Gen 12 onwards, including the making of a covenant (Gen 15:17–21), the sealing of that covenant by circumcision (Gen 17:1–27), the promise of a son to Abraham (Gen 18:1–15) and the arrival of that son, Isaac (Gen 21:1–7).

The ceremony at Shechem, as recounted in Joshua 24, continues with a brief mention of Isaac, Jacob and Esau (24:3–4) before noting that “Jacob and his children went down to Egypt” (24:4). This is the story that is recounted in Genesis 21 through to 50, which ends with a reminder that “God will surely come to you, and bring you up out of this land to the land that he swore to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob” (Gen 50:24).

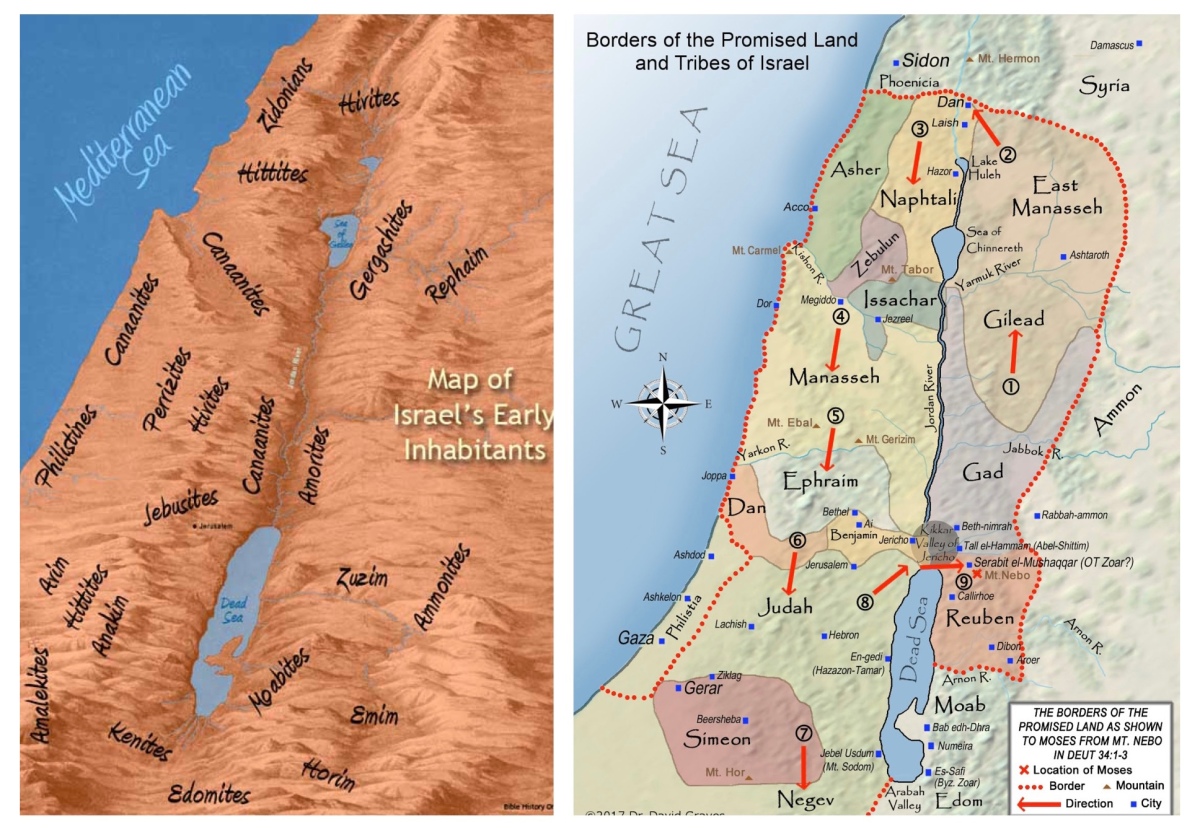

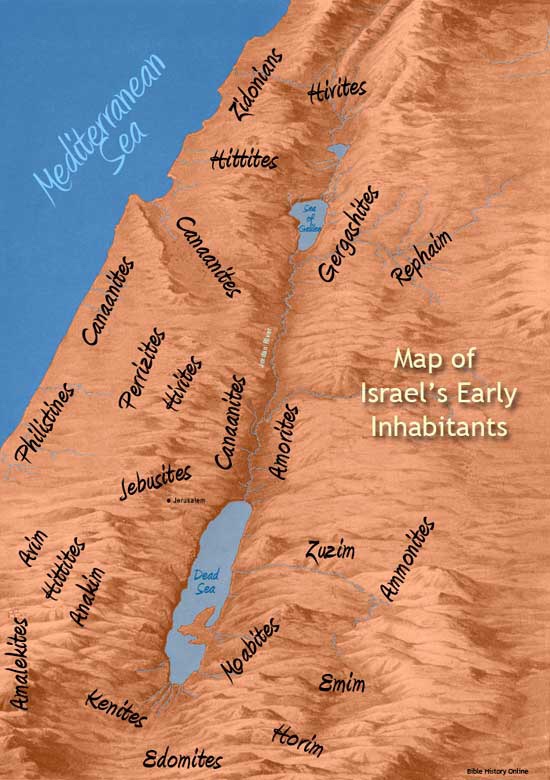

The story of the people of Israel leaving Egypt and wandering in the wilderness is recalled in Josh 24:5–7, summarising the lengthy narrative of Exodus 3—17, before remembering the early forays into the land promised, the land of Canaan (Josh 24:8–12). This culminates in the words, “I gave you a land on which you had not labored, and towns that you had not built, and you live in them; you eat the fruit of vineyards and oliveyards that you did not plant” (24:13). That is the point in the narrative at which the story of Joshua stands—whilst some of the land has been occupied, the people are still to mount the campaigns that will see them claim the whole of that land.

What follows is a pledge of loyalty made by the people, in response to the urging of Joshua to “revere the Lord, and serve him in sincerity and in faithfulness” (24:14). The people recall all that God had done for them: he “brought us and our ancestors up from the land of Egypt … did those great signs in our sight … protected us along all the way that we went … and drove out before us all the peoples who lived in the land” (24:17–18). Their declaration is, “we also will serve the Lord, for he is our God” (24:18).

The ceremony that follows under Joshua (Josh 24:24–28) contains five components, each one of which has resonances with the covenant made with Israel in the time of Moses (Exod 19 and 24). This narrative is brought to consistency wi the earlier account in Exodus through the work of the priestly redactors at work in the Exile, as they collated, wrote down, and shaped a narrative of the saga of Israel’s origins.

First, when the people repeat their vow, “The Lord our God we will serve, and him we will obey” (Josh 24:24, repeating v.18), they are echoing the earlier occasion when Moses “summoned the elders of the people, and set before them all these words that the Lord had commanded him” (Exod 19:7). At that moment, we are told that “the people all answered as one: ‘Everything that the Lord has spoken we will do’” (Exod 19:8).

Second, the text declares that “Joshua made a covenant with the people that day, and made statutes and ordinances for them at Shechem” (Josh 24:25). This evokes the earlier covenantal offer by God at Sinai, “if you obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession out of all the peoples” (Exod 19:5), as well as the subsequent actions of Moses which signalled acceptance of that covenant (Exod 24:6–8).

The Exodus narrative (itself shaped by the later priestly redactional undertaking) reports that Moses dashed half of the blood against the altar (24:6), read from the book of the covenant—to which the people once again affirmed, “All that the Lord has spoken we will do, and we will be obedient” (24:7), and then dashed the other half of the blood on the people, and said, “See the blood of the covenant that the LORD has made with you in accordance with all these words” (24:8).

Third, we learn that “Joshua wrote these words in the book of the law of God; and he took a large stone, and set it up there under the oak in the sanctuary of the Lord” (Josh 24:26). This is a clear reflection of the action of Moses at Sinai, when “he built an altar at the foot of the mountain, and set up twelve pillars, corresponding to the twelve tribes of Israel” (Exod 24:4). Of course, the stone is also present in the tablets of stone which God gave to Moses (24:12), “written with the finger of God” (Exod 31:18).

The stone set up at Shechem might well also connect with the twelve stones that Joshua had taken from the River Jordan when the people had crossed over into the land of Canaan, to be “laid down in the place where you camp tonight” (Josh 4:1–9). Those twelve stones, one for each tribe, were to be “a memorial forever” to the Israelites (4:7), and were placed at Gilgal, the place of transition into the land. Gilgal was the place where all the male Israelites were circumcised (5:1–9), the Passover was celebrated (5:10–11), and the daily gift of manna, provided throughout the wilderness years, ceased (5:12). See

Fourth, Joshua tells the people, “See, this stone shall be a witness against us; for it has heard all the words of the Lord that he spoke to us; therefore it shall be a witness against you, if you deal falsely with your God” (Josh 24:27). The large stone at the holy site of Shechem reflects the altar of stone at Sinai which Moses was commanded to build: “do not build it of hewn stones; for if you use a chisel upon it you profane it” (Exod 20:25). The stone bears witness to the people at Shechem, just as the stone altar and tablets bore witness at Sinai.

Finally, the narrator indicates that “Joshua sent the people away to their inheritances” (Josh 24:28)—namely, into those parts of the land which had been allocated to them in the earlier chapters of this book. This provides a fulfilment of the journey that the people had been undertaking, ever since Moses had sealed the covenant with the Lord at Sinai. From that time, “the cloud of the Lord was on the tabernacle by day, and fire was in the cloud by night, before the eyes of all the house of Israel at each stage of their journey” (Exod 40:38).

So the ceremony recorded in Joshua 24 is a renewal of the covenant made with Moses. This covenant would be renewed yet again in the time of King Josiah, after the discovery of “a book of the law” and his consultation with the prophet Huldah (2 Chron 34:29–33).

It was renewed yet again after the exiled people of Judah returned to the land under Nehemiah, when Ezra read from “the book of the law” for a full day (Neh 7:73b—8:12) and the leaders of the people made “a firm commitment in writing … in a sealed document” which they signed (Neh 9:38–10:39). This is the renewal of the covenant with the people which is signalled in the words of the prophet Jeremiah (Jer 31:31–34).

The particular expression of renewal that Jeremiah articulates proved to be critical for the way that later writers portray the covenant renewal undertaken by Jesus of Nazareth (1 Cor 11:25; Luke 22:20; 2 Cor 3:6–18; Heb 8:8–12). Especially significant is the claim that this renewed covenant “will not be like the covenant that I made with their ancestors when I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt—a covenant that they broke” (Jer 31:32).

Jeremiah indicates that God “will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (31:33). This is a covenant which has “the forgiveness of sins” at its heart (31:34)— precisely what is said of the “new covenant” effected by Jesus (Matt 26:28; and see Acts 5:31; 10:43; 13:38; 26:18).

The story in Joshua 24 that we hear this coming Sunday thus stands firmly in the stream of significant biblical passages which tell of the covenant between the Lord God and the people of God, offered and received and renewed a number of times throughout the long story of the people of Israel, from ancestral times through to the time of Jesus.