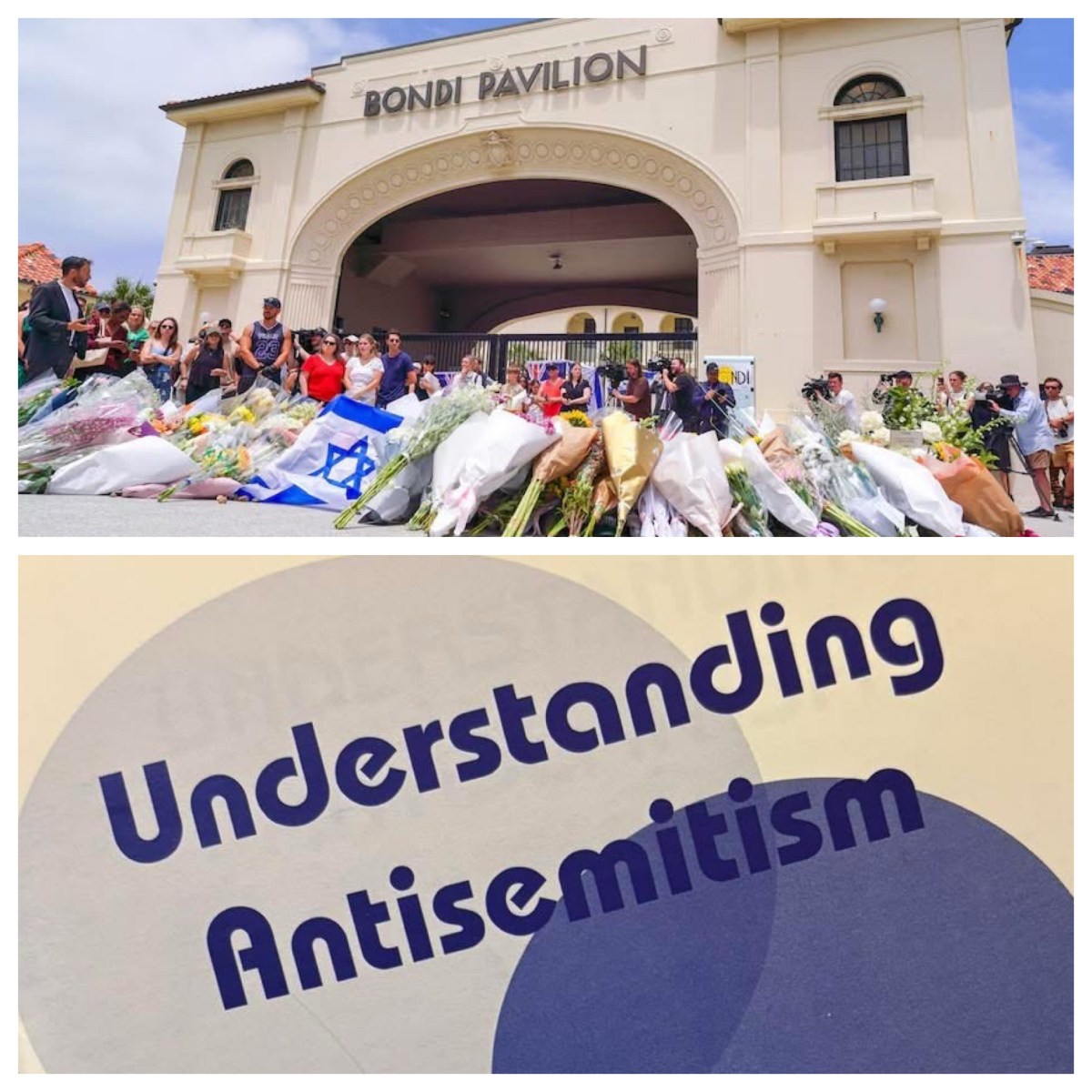

It’s less than a week since the tragic mass shooting at Bondi Beach. In the days since then, we have seen very public displays of shock, grief, fear, anger, blame, rage, and other strong emotions. So many comments rip over into recrimination and dehumanisation. It’s been savage. Alongside all of this, there has also been a deep admiration for those who attempted to stop the shooting by intervening—at the cost of their lives, in one instance, and incurring significant wounds, in another case.

There have been all manner of suggestions about what should be done to address the reasons for this happening—even as the relevant authorities undertake their careful, methodical work of investigating who, how, and why this came to pass. The Federal Government has already flagged changes to the gun laws in force around the country, and more recently has signalled that legislation will be introduced to tighten the application of “hate speech” laws. These responses are important, and good. We can only hope that the parliaments concerned—Federal and State—all work cohesively to adopt them expeditiously.

But I don’t believe that a legislative response—as important, and necessary, as that is—will address the root cause of the issue that everyone is regarding as the villain in the situation. It’s about more than what our laws say. Laws are important; they set the bounds beyond which words and actions are deemed to be unacceptable in our society. Laws, put into place by legislation which parliaments enact, provide the outer framework of society. Our laws signal who we are as a society: what we value, what we disdain, what we will not tolerate. (That’s why politicians are necessary; they staff the parliaments that do this essential work on our behalf.)

But there is more to be said. Addressing antisemitism is not just a matter of legislation, or politics. It is a matter of culture; the features of our common life which are deeply embedded in who we are, and which are expressed in our attitudes, our words, and our actions. It is our culture which needs addressing.

1

We have heard widespread public rhetoric about “antisemitism”. It has, indeed, been a growing refrain since the events of 7 October 2023 in Gaza and Israel, but has been almost at saturation point since the tragic event at Bondi Beach on 14 December 2025. It is quite clear that there has been a significant rise in the number of antisemitic events since October 2023, culminating in the death of 15 Jews and significant injuries to another 40 or so at Bondi.

A lot of that rhetoric seems to assume that the upsurge of antisemitism over the past two years has caught us by surprise; it is a shock, a terrible result of protests about what has been happening in Gaza in recent times, an unprecedented feature of Australian society as the politics of far away have infiltrated and impacted our domestic scene. But that is not the case. Whilst the number of intensity of these antisemitic events has indeed risen in that time, this is not a new experience for Jewish people in Australia.

Antisemitism has been present in Australian society for decades. For 12 years I was part of the Uniting Church National Dialogue with the Jewish Community (2000–2012). Elizabeth joined me as a member for the last six of those years. For some time, I was the UCA co-chair of the Dialogue. The Jewish co-chair was usually the late Jeremy Jones, a renowned advocate for Jews in Australia. See https://uniting.church/an-introduction-to-the-uca-jewish-dialogue/

Every six months when we met, Jeremy would report on the rates of antisemitic incidents. It was constant, distressing, and unacceptable. He had begun collating such incidents in 1989. In 2004, he published an article, entitled “Confronting Reality: Anti-Semitism in Australia Today”, in the Jewish Political Studies Review (vol.16 no.3/4, Fall 2004, pp.89–103). The thesis he developed was clear; despite the view that Australia has been “not only accepting but welcoming of Jews … In recent years, however, there has been a growing acknowledgment both of the presence of anti-Semitism in Australia, and that it is the responsibility of political and moral leadership to confront it.” See https://www.jstor.org/stable/25834606

A decade later, in a 2013 report on “Antisemitism in Australia” published by the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, he noted that “During the twelve months ending September 30, 2013, 657 reports were recorded of incidents defined by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (now the Australian Human Rights Commission) as ‘racist violence’ against Jewish Australians.” The kinds of incidents that he tabulated “included physical assault, vandalism – including through arson attacks – threatening telephone calls, hate mail, graffiti, leaflets, posters and abusive and intimidatory electronic mail”.

There can be no doubt that antisemitism was firmly ingrained in Australian society at that time. Indeed, as Jeremy Jones noted, the figures reflected “a twenty one per cent increase over the previous twelve month period, and sixty-nine percent above the average of the previous 23 years.” See https://www.ecaj.org.au/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2013-ECAJ-Antisemitism-Report.pdf

Indeed, I well recall what security measures were in place on those occasions when I visited a Jewish synagogue in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney, starting almost 30 years ago. I was teaching a course entitled “The Partings of the Ways”, exploring how Christianity separated from Judaism. One element in the course was to attend Jewish worship, and meet with the rabbi for a question-and-answer session. Rabbi Jeffrey Kamins of Temple Emanuel was always very amenable to spending time with the class in this way. (He also came to North Parramatta to give a guest lecture in the class each year.)

Entry into the synagogue was through a security gate at the front, in the middle of a high, strong security fence that surrounded the building and grounds. A security guard checked each of us before permitting entry. Once inside, we received wonderfully warm hospitality; but the first impression was rather chilling. The reason for that, even back in the 1990s, was that Jewish synagogues recognised that they needed to implement these security measures to ensure the safety of worshippers. Antisemitic incidents—angry words, slogans painted on walls, and physical attacks—were being experienced by Jews on a regular basis. Antisemitism was, unfortunately, alive and well.

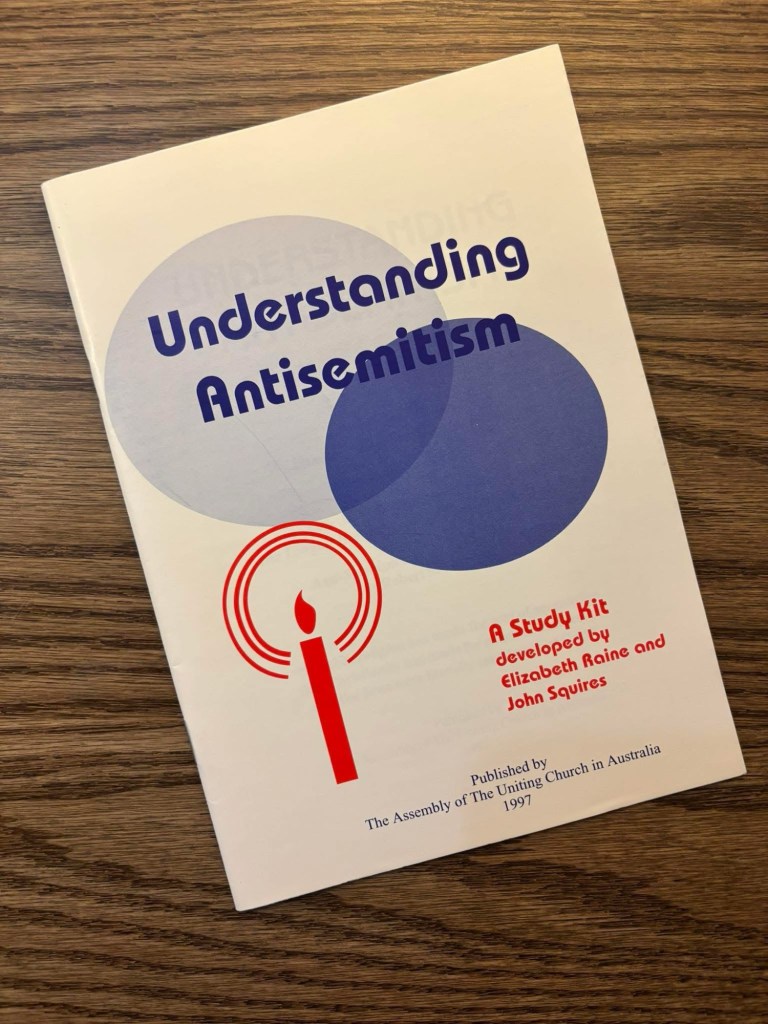

In fact, in 1997, the Uniting Church National Assembly had adopted a statement about our relationships with Jewish people, which explicitly included a rejection of antisemitism and encouraged church members to become informed about such matters.

In the course of preparing that statement, Elizabeth and I were charged with preparing a resource, which the Assembly published as a study with ten sessions, and which was disseminated across the church.

I wonder how many congregations made use of this resource? We certainly used many elements of it in our regular teaching over the years.

The resource is available online at https://illuminate.recollect.net.au/nodes/view/11763?

2

Some voices now, in 2025, are placing the responsibility for what happened at Bondi firmly on the shoulders of the Federal Government, arguing that they knew about the dangers of antisemitism but “did nothing”. Albanese should resign, they say. It was his fault that this tragedy happened. He has blood on his hands. It’s strong stuff.

I wonder. We have had many Prime Ministers over the past 25 years, since I first started hearing those regular reports about antisemitism from Jeremy Jones. I wonder why other PMs have not been equally accused of inaction, like Albanese. What did John Howard do? Or Kevin Rudd? Or Julia Gillard? Or Tony Abbott? Or Malcolm Turnbull? Or Scott Morrison?

All of these Prime Ministers did, in fact, the same as Albanese: recognising that antisemitism existed, they supported low level anti-racism programmes, and blithely went on with their political business of elections, budgets, legislation, and the argy-bargy of Question Time. Little has changed over all that time. Antisemitic incidents have continued to take place. And how many of the people now making loud noises about the Bondi Beach event had actually been agitating five, ten, or twenty years ago about antisemitism?

And it is not entirely clear that it was, in fact, antisemitism which fuelled the terrible events at Bondi Beach. Carrick Ryan, who spent years working as a Federal Agent from the NSW Joint Counter Terrorism Team, has written that he sees this as “an act of terrorism perpetrated by mad men possessed by a dangerous ideology”.

His view is that “Jihadists do not have a political goal. They are inspired by a toxic interpretation of their faith that encourages them to die in an act of violence against any perceived enemy of their faith.” He argues that “it is simply absurd to suggest they have been influenced by pro-Palestinian university protesters, Greens politicians, or even ‘anti-Zionist’ conspiracy theorists.”

“The men who conducted these attacks”, he maintains, “would have despised those activists as much as anyone on the political right, and as I have tried to explain to many activists who have attempted to romanticise Hamas as heroic freedom fighters, the future they are aspiring to is very different.” It’s not about antisemitism, so much as it is it an expression of religious fanaticism.

3

However, it is not only antisemitism which has been growing. Islamophobic incidents have increased consistently as the Muslim population of Australia has grown. Deakin and Monash Universities are collaborating to compile an annual Islamophobia Report, documenting such incidents since 2014. The latest report notes that the number of Islamophobic incidents has increased significantly since 7 October 2023. You can read the reports at https://islamophobia.com.au

There are numerous other incidents involving First Nations people, Afghanis, Asians, Sudanese, and all manner of diverse ethnic minorities which have all continued in the same period, spiking in numbers at particular times, with the same minimalist level of government response. All Together Now is an independent not-for-profit organisation and registered charity, founded in 2010, that holds to a vision of a “racially equitable Australia”. They work towards this vision “by imagining and delivering innovative and evidence based projects that promote racial equity”. Their website declares “we are community driven, we utilise partnered approaches, and our work is intersectional”.

As All Together Now draws together a range of studies, it reports that “40% of children experience racism in schools … 43% of non-white Australian employees commonly experience racism at work …there is still a culture of systemic racism in Australian sports … studies have exposed systemic and structural forms of racism in policing, the justice system and child protection, leading to discrimination, violence and death of people of colour and First Nations People”. All the studies they cite are referenced and hyperlinked on their website at https://alltogethernow.org.au/racism/racism-in-australia/

Our society has fostered far too many intolerant, aggressively-hostile individuals who feel they have a right to speak and act in these ways.

4

The Bondi event and its repercussions are not simply a partisan political matter, as so many loud voices are currently proclaiming. It is a cultural phenomenon; the “right” to criticise, slander, marginalise, and attack Jews … and Muslims … and First Peoples … and other minorities … has been taken for granted by an increasing proportion of the population. They have, of course, been egged on by extremist politicians who seize every opportunity to foster racism.

Antisemitism, and Islamophobia, and all forms of racism, together form a deeply-embedded cultural phenomenon, for which we are all responsible. Politicians have a role to play (and wouldn’t it be good if a bipartisan approach could be consistently made) but all of us have things we can, and should, do, each and every day.

Calling out racist, islamophobic, or antisemitic language is one thing we could aim for. Intervening in low-level incidents is another, when it appears safe to do so. Supporting the education of children and young people with programmes which inculcate social responsibility, ethical behaviour, and respectful interactions with others is important. Joining groups which are advocating for justice for minority groups which are marginalised is something that people could do. Writing to state and federal members of parliament about issues of concern in these areas is also something that people could do.

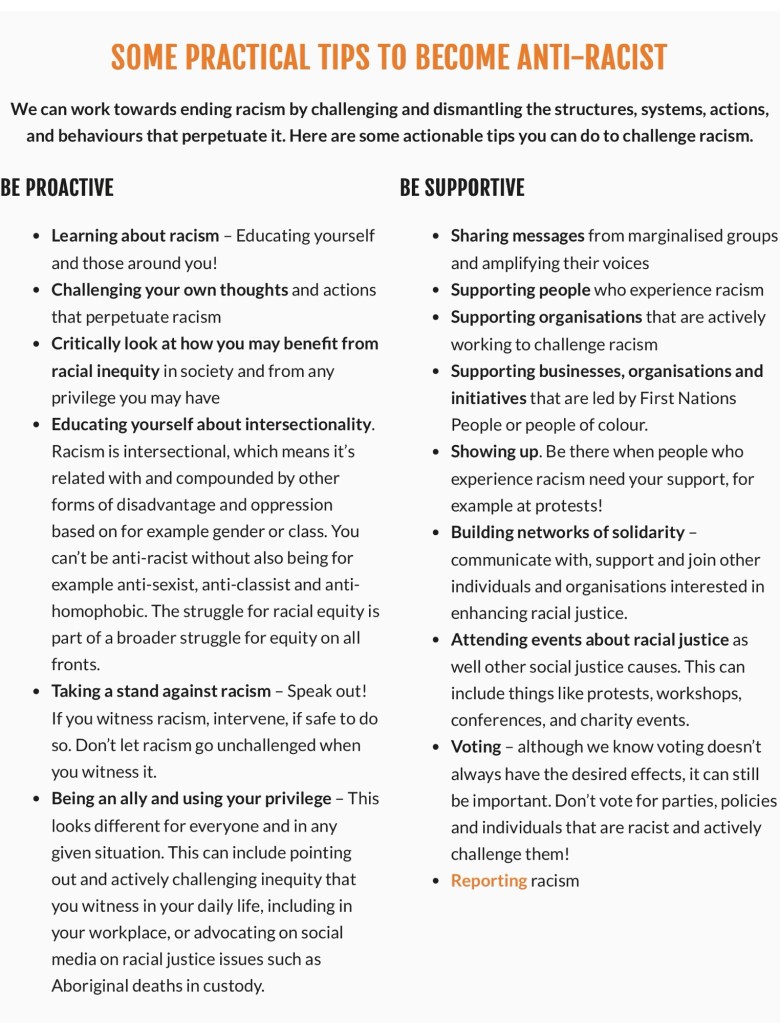

All Together Now has a helpful collection of “Practical Tips to Become Anti-Racist” as well as a useful guide with links to further resources. We would all do well to read, ponder, and implement the kinds of things that they advocate.

*****

For my earlier reflections on this tragic event, “They are part of the whole of us”, see