A sermon preached by the Rev. Elizabeth Raine at Tuggeranong Uniting Church on Sunday 24 October 2021.

*****

Last time we were with Job, he and his three friends had reached an impasse. Job believed them to see blindly and listen deafly. They, on the other hand, cannot understand Job’s stubbornness. Enter the fourth friend, Elihu.

Elihu, whose name means ‘My God is He’, and whose nose is burning in anger in regard to the conversation to date, strongly condemns the approach taken by the three friends and argues that Job is misrepresenting God’s justice and discrediting God’s character. In his speech, Elihu describes God as mighty, yet just, and quick to warn but also quick to forgive. Elihu is almost cast into a prophetic role, and prepares the way for the appearance of God, who finally shows up.

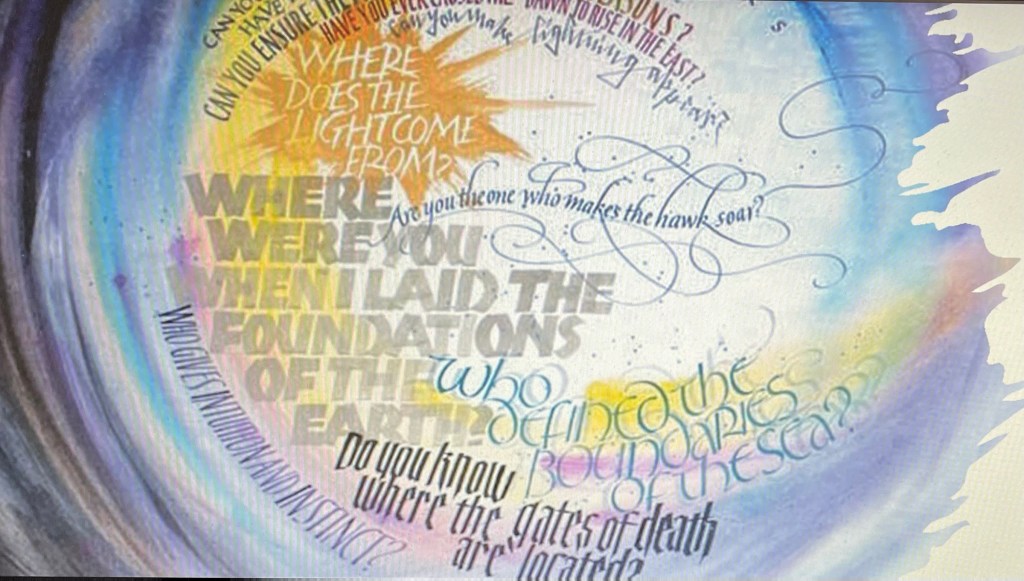

God has arrived in a whirlwind, and to compensate for his long silence of 35 chapters he now responds to Job with a flood of rather sarcastic questions. There is a touch of irony here in God’s chosen vehicle – in 9:17 Job had said If I summoned him and he answered me, I do not believe he would listen to my voice, for he tramples me down with a whirlwind, enlarges my wounds for no reason and will not let me get my breath.

God appears to do just this, his intent apparently being to adjust Job’s attitude by telling him a few things, including some pretty prolonged boasting about his cosmic power, culminating in the description of the monstrous Leviathan and Behemoth. By this God therefore puts cosmic matters – including Job’s smallness and frailness when compared to these two monstrous creations – into their true perspective.

Twice he reminds Job to gird your loins like a real man. I will ask questions, and you instruct me (38:2; 40:7).

To “gird the loins” is usually used as a metaphor for preparing for battle. It is hard to conceive that the unfortunate Job, who has just been told he “darkens counsel” with “ignorant” words, who has a whirlwind of cosmic proportions roaring around him, is in any position to instruct the deity or do battle with him. The deck is stacked, and this is a contest that we know God must win.

The response God gives Job is not the expected one. God’s words are not what the friends have imagined that God would say, nor are they the vindication that Job had hoped for. God has reversed the scenario that Job had earlier envisaged. Instead of Job challenging God in court about the justice of God’s actions, God counters with his own case, asking Job to reveal his wisdom. Instead of the divine actions being interpreted by a powerless human, they are now presented from God’s point of view.

The speech of God to Job is the climax of the book but it offers no explanation for Job’s suffering. The question: where was Job when God created the world? is an unsatisfactory ‘answer’, and we are left with the uncomfortable possibility that God acts in capricious ways, an unsympathetic deity who would allow the life of a man, his family and his servants and animals to be tormented or cut short for no better reason than to prove a point to the Adversary.

The meaning and significance of this divine speech of God continues to be a widely debated issue. Some interpret God’s words as a negation of a human being’s right to question God. Others see them as a correction to Job’s limited understanding of good and evil. Still others believe this scene shows Job’s faith and humility. Yet others believe that the words of God avoid Job’s questions, suggesting that there is doubt cast over God’s justice and compassion.

To answer God’s somewhat sarcastic questions would require the knowledge of a god, not a human. Job’s limitations are exposed, and the workings of God are declared to be a mystery beyond Job’s understanding. Instead of being offered comfort, Job is reminded of his ignorance and frailty. What are we to make of this disconcerting picture of God, especially since the questions Job asks may also be our own?

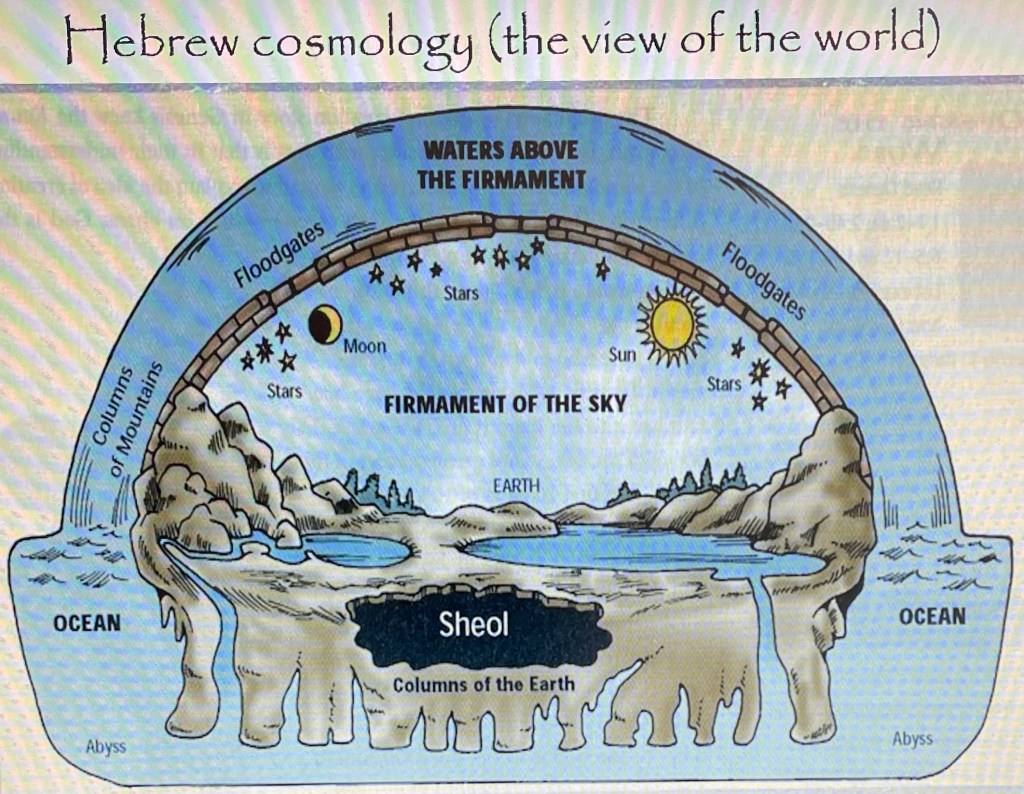

The speeches of God to Job illustrate the world according to Hebrew cosmology. The world is seemingly ordered, and everything has its place. The sea has its limits, cosmic darkness is behind gates, the sky has statutes and the clouds are numbered. But there are disorderly elements as well. The wild beasts have both hunter and prey among their numbers, yet God provides for both, giving to one the freedom to eat and another to be eaten.

In his ignorance, Job has imagined a black and white world where evil and good, reward and punishment are clearly defined. Hence his insistence that he be shown justice. But here he is presented with a world of moral ambiguity, where the wild ass is just as likely or not to be eaten by the lion in search of food.

The world as God has created it is presented as full opposing forces such as life and death, chaos and order, freedom and control, wisdom and foolishness, ordinary and bizarre, evil and good, and Job’s assumption that in a just universe his piety should have been rewarded with prosperity, is rendered meaningless. The world is not ordered according to guilt or innocence so there is no easy answer to the problem of innocent suffering.

Creatures die so others may survive. Chaos and death are not eliminated by God but operate within the boundaries of his design and the world’s complexity means it is not possible for a simple and mechanical law of reward and punishment to operate. The various aspects of human morality that Job and his friends have discussed at length are not the way the universe works. God presents a universe which is independent of such human belief systems. As Job’s beliefs fall about him in ruins, he is faced with a deity whose ways are outside of human comprehension and wisdom.

The book of Job began with deprivation and tragedy. In the final verses though, we find abundant restoration, with Job receiving back his house and family and twice as much as he had lost. Job wisely acknowledges the supreme power of God, his own ignorance, and renounces his dust and ashes.

Note that Job does not repent in sackcloth and ashes but repents of them. This suggests that he is still a touch defiant, but he has learnt he is not the centre of the universe and it is now time to resume normal life again in the verses that follow. And with a final touch of irony, the friends who wanted Job to plead for God’s mercy for himself now find themselves in need of Job’s intercessions on their behalf.

It seems a happy ending, but despite its complex setting and arguments, the book of Job has presented us with more problems than solutions. Curiously, verse 42:10 states that restoration is made to Job because he prayed for his friends, not because he repents. Even more surprisingly, Job’s friends and relatives then console him about the evil that God had brought upon him, a statement that lays the blame for Job’s suffering directly with God, and not the Adversary. They offer gold and silver as a token of their goodwill. The implication is that God does cause innocent suffering, as part of the cosmic design.

So where do we go from here? Do we dwell on a dangerous universe where God doesn’t answer the questions of Job and where justice seems questionable? Or is there another way forward in this rather dark story?

Professor Kathryn Schifferdecker[1], in her commentary on Job on Working Preacher, notes the details of this restoration have some unusual features. She states that

Job’s three daughters are the most beautiful women in the land, and Job gives them an inheritance along with their brothers, an unheard-of act in the ancient Near East. He also gives them unusually sensual names: Dove (Jemimah), Cinnamon (Keziah) and Rouge-Pot (Keren-happuch).

Schifferdecker believes that Job has “learned to govern his world as God does.” What does she mean by that?

The cautious father of the prologue who offered sacrifices for his children in case they had sinned now has become a parent modelled on God’s own creation. By giving them their inheritance, he is giving his children the same freedom to live and grow and learn that God gives God’s creation, and, like God, he delights in their freedom and in their beauty.4

Ellen Davis, in her book Getting Involved with God: Rediscovering the Old Testament[2] writes, “The great question that God’s speech out of the whirlwind poses for Job and every other person of integrity is this: Can you love what you do not control?”

It is a question, says Schifferdecker, that is worth pondering. “Can you love what you do not control: this wild and beautiful creation, its wild and beautiful Creator, your own children?” she asks? [3]

Davis also puts forward the case that we should not be concentrating on why or how much it costs God to restore Job’s fortunes, as it obviously costs God nothing. “The real question is how much it costs Job to become a father again.”[4]

I really like this perspective. Job, says Schifferdecker, resembles a Holocaust survivor whose greatest act of courage may have been to start again and bear children. Yet despite the potential risks, Job chooses to enter life again. Job and his wife, despite their terrible experiences, choose to again “bring children into a world full of heart-rending beauty and heart-breaking pain. Job chooses to love again, even when he knows the cost of such love”. (Schifferdecker, 2012)[5].

Having cited so much of her, I am going to give the last words to Professor Schifferdecker, as I think she sums it up beautifully:

Living again after unspeakable pain is a kind of resurrection. The book of Job does not espouse an explicit belief in resurrection. Nevertheless, the trajectory of the whole book participates in that profound biblical movement from death to life. It is not surprising, therefore, that the translators of the Septuagint add this verse to the book of Job: “And Job died, old and full of days. And it is written that he will rise again with those whom the Lord raises up.”

And perhaps that is an appropriate place to leave this story of Job, waiting with God’s other servants for the world to come. This complex work, the book of Job, plumbs the depths of despair and comes out on the other side into life again. In this movement, it testifies not only to the reality of inexplicable suffering but also to the possibility of new life — life lived out in relationship with the God of Israel, the God of resurrection, who, as both synagogue and church proclaim, is faithful even until death, and beyond. [6]

****

See other sermons in the series at

https://johntsquires.com/2021/10/02/living-through-lifes-problems-job-1-pentecost-19b/

https://johntsquires.com/2021/10/10/hope-in-a-broken-world-job-23-pentecost-20b/

https://johntsquires.com/2021/10/17/celebrating-creation-job-38-and-psalm-104-pentecost-21b/

and also

https://johntsquires.com/2021/10/20/job-a-tale-for-the-pandemic-part-one-pentecost-19b-to-22b/

https://johntsquires.com/2021/10/20/job-a-tale-for-the-pandemic-part-two-pentecost-19b-to-22b/

[1] Schifferdecker, K. Commentary on Job 42:1-6, 10-17, Working Preacher, 2012 (Accessed 20/10/2021 https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/ordinary-30-2/commentary-on-job-421-6-10-17 )

[2] Davis, E.F. “The Sufferer’s Wisdom,” Getting Involved with God: Rediscovering the Old Testament (Cambridge, MA: Cowley, 2001), 121-143.

[3] Schifferdecker, K. Commentary on Job 42:1-6, 10-17 ,Working Preacher, 2012

[4] Davis, E.F. (2001) 121-143

[5] ibid

[6] ibid