“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind” (Deuteronomy 6:5). “You shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Leviticus 19:8). These two commandments are cited in a story about Jesus engaging in a discussion with a scribe, a teacher of the Law, which ends with Jesus saying, “there is no commandment greater than these” (Mark 12:31).

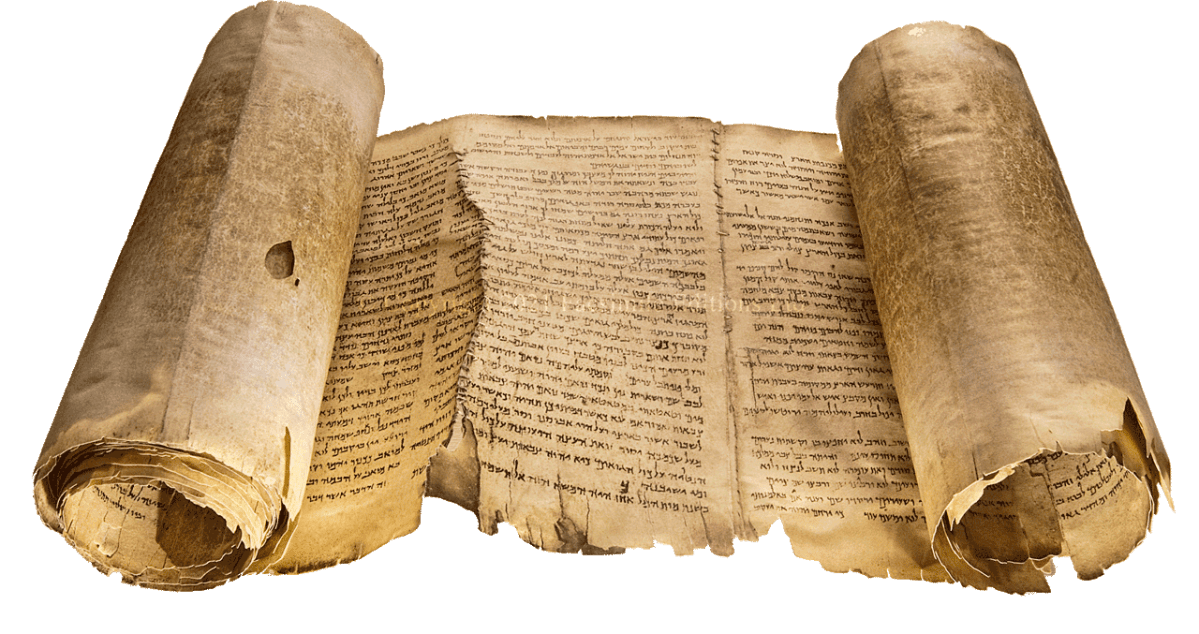

The Narrative Lectionary includes this story (Mark 12:28–34) as the opening section of a longer Gospel passage that is proposed for worship this coming Sunday (12:28–44). It’s a passage that takes us deep into the heart of Torah—those guidelines for living all of life in covenant faithfulness with God. Torah sits at the centre of Judaism. See more on this at

Of course, Jesus hasn’t answered the question precisely in the terms that it was asked; he doesn’t indicate what is “the first” commandment, but which two are “greatest”. It’s like a dead heat in an Olympic race: a race when even a finely-tuned system can’t differentiate between the two winners, even down to one thousandth of a second. Both love of God and love of neighbour are equally important. Joint winners—like that high jump competition a year or two back where the two leading jumpers just decided to share the gold medal, rather than keep competing—and risk not getting gold.

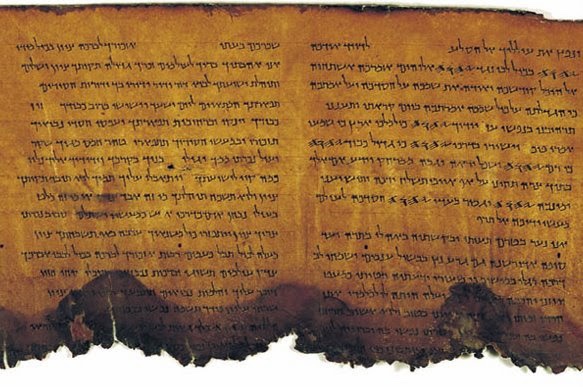

Both commands are biblical commands, found within the foundational books of scripture within Judaism. They were texts that Jewish people, such as Jesus and his earliest followers would have known very well. Each command appears in a significant place within the books of Torah, the first five books of Hebrew Scriptures.

The command to “love God” sits at the head of a long section in Deuteronomy, which reports a speech by Moses allegedly given to the people of Israel (Deut 5:1–26:19). The speech rehearses many of the laws that are reported in Exodus and Leviticus, framing them in terms of the repeated phrases, “the statutes and ordinances for you to observe” (4:1,5,14; 5:1; 6:1; 12:1; 26:16–17), “the statutes and ordinances that the Lord your God has commanded you” (6:20; 7:11; 8:11).

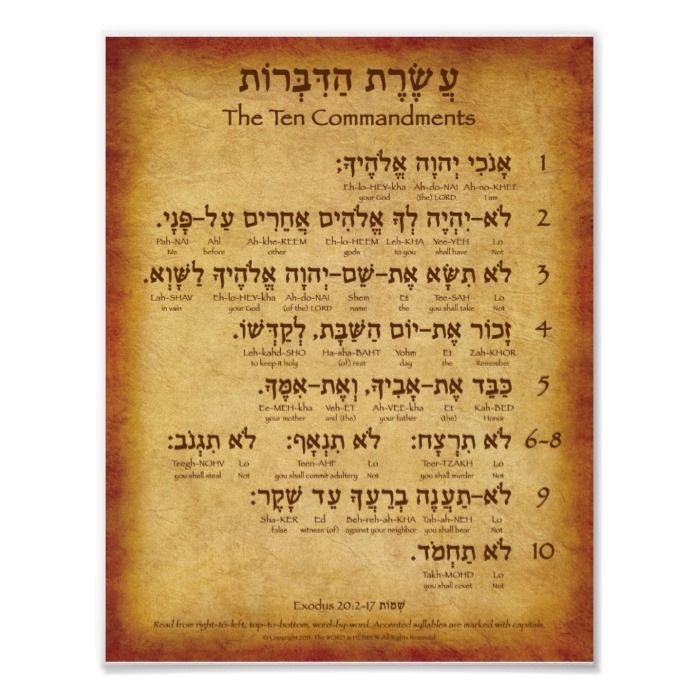

After proclaiming the Ten Commandments which God gave to Israel through Moses (Deut 5:1–21; cf. Exod 20:1–17) and rehearsing the scene on Mount Sinai and amongst the people below (5:22–33; cf. Exod 19:1–25; 20:18–21). Moses then delivers the word which sits at the head of all that follows: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD is our God, the LORD alone. You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. Keep these words that I am commanding you today in your heart” (Deut 6:4–6). This, it would seem, is the key commandment amongst all the statutes and ordinances.

These words are known in Jewish tradition as the Shema, a Hebrew word literally meaning “hear” or “listen”. It’s the first word in this key commandment; and more broadly than simply “hear” or “listen”, it caries a sense of “obey”. These words are important to Jews as the daily prayer, to be prayed twice a day—in keeping with the instruction to recite them “when you lie down and when you rise” (Deut 6:7). As these daily words, “love the Lord your God” with all of your being are said, they reinforce the centrality of God and the importance of commitment to God within the covenant people.

The command to “love your neighbour” in Leviticus 19 culminates a series of instructions regarding the way a person is to relate to their neighbours: “you shall not defraud your neighbour … with justice you shall judge your neighbour … you shall not profit by the blood of your neighbour … you shall not reprove your neighbour … you shall love your neighbour” (Lev 19:13–18).

These instructions sit within the section of the book which is often called The Holiness Code—a section which emphasises the word to Israel, that “you shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy” (Lev 19:2; also 20:7, 26). Being holy means treating others with respect. Loving your neighbour is a clear manifestation of that ethos. Loving your neighbour exemplifies the way to be a faithful person in covenant relationship with God.

So it is for very good reasons that Jesus extracts these two commandments from amongst the 613 commandments that are to be found within the pages of the Torah. (The rabbis counted them all up—there are 248 “positive commandments”, giving instructions to perform a particular act, and 365 “negative commandments”, requiring people to abstain from certain acts.)

Jesus, of course, was a Jew, instructed in the way of Torah. He knew his scriptures—he argued intensely with the teachers of the Law over a number of different issues. He frequented the synagogue, read from the scroll, prayed to God, and went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem and into the Temple—where, once again, he offered a critique of the practices that were taking place in the courtyard of the Temple (11:15–17).

Then he engaged in debate and disputation with scribes and priests (11:27), Pharisees and Herodians (12:13), and Sadducees (12:18). Each of those groups came to Jesus with a trick question, which they expected would trap Jesus (12:13). Jesus inevitably bests them with his responses (11:33; 12:12, 17, 27). It was at this point that the particular scribe in our passage approached Jesus, perhaps intending to set yet another trap for him (12:28).

So Jesus, good Jew that he was, is well able to reach into his knowledge of Torah in his answer to the scribe. The commandments that he selects have been chosen with a purpose. They contain the essence of the Torah. His answer draws forth the agreement of the scribe—there will be no robust debate now! In fact, in affirming Jesus, the scribe reflects the prophetic perspective, that keeping the covenant in daily life is more important that following the liturgical rituals of sacrifice in the Temple (see Amos 5:21–24; Micah 6:6–8; Isaiah 1:10–17).

The scene is similar to a Jewish tale that is reported in the Babylonian Talmud, a 6th century CE work. In Shabbat 31a, within a tractate on the sabbath, we read: “It happened that a certain non-Jew came before Shammai and said to him, ‘Make me a convert, on condition that you teach me the whole Torah while I stand on one foot.’ Thereupon he repulsed him with the builder’s cubit that was in his hand. When he went before Hillel, he said to him, ‘What is hateful to you, do not to your neighbour: that is the whole Torah, the rest is the commentary; go and learn it.’”

Hillel, of course, had provided the enquiring convert, not with one of the 613 commandments, but with one that summarised the intent of many of those commandments. We know it as the Golden Rule, and it appears in the Synoptic Gospels as a teaching of Jesus (Matt 7:12; Luke 6:31).

Some Jewish teachers claim that the full text of Lev 19:18 is actually an expression of this rule: “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbour as yourself: I am the LORD.” Later Jewish writings closer to the time of Jesus reflect the Golden Rule in its negative form: “do to no one what you yourself dislike” (Tobit 4:15), and “recognise that your neighbour feels as you do, and keep in mind your own dislikes” (Sirach 31:15).

Paul clearly knows the command to love neighbours, for he quotes it to the Galatians: “the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself’” (Gal 5:14), and James also cites it: “you do well if you really fulfill the royal law according to the scripture, ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself’” (James 2:8). Both writers reflect the fact that this was an instruction that stuck in people’s minds!

And I wonder … perhaps there’s a hint, in these two letters, that the greater of these two equally-important commandments is actually the instruction to “love your neighbour”?

*****

I have provided a more detailed technical discussion of the words used in this passage, and its Synoptic parallels, in this blog:

On the Pharisees and Torah, see