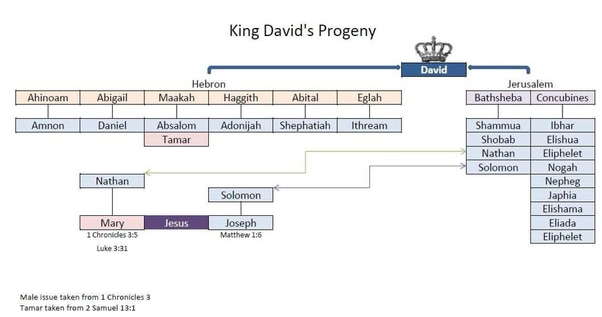

For the passage from Hebrew Scripture this coming Sunday, the lectionary offers us selected verses from 2 Sam 6:1–19. Last week, we heard the brief account of how David, the king of Judah, took the city of Jerusalem from its inhabitants, the Jebusites, and was anointed as king of “all Israel” (5:1–10). Next week, we will hear of the promise that God makes to David, that “I will make for you a great name … your throne shall be established forever” (7:1–14).

In between these two pivotal events, establishing beyond doubt that David was both the conqueror supreme of the earlier inhabitants and the progenitor of a dynasty—“the house of David”—that would hold power for centuries to come, we have a curious, yet significant, account relating to The Ark of the Covenant (6:1–19). See

David uses the Ark to reinforce and undergird his authority; his intention in bringing into the city, Jerusalem, was to confirm absolutely that he was God’s anointed, in Jerusalem, ruling over all Israel.

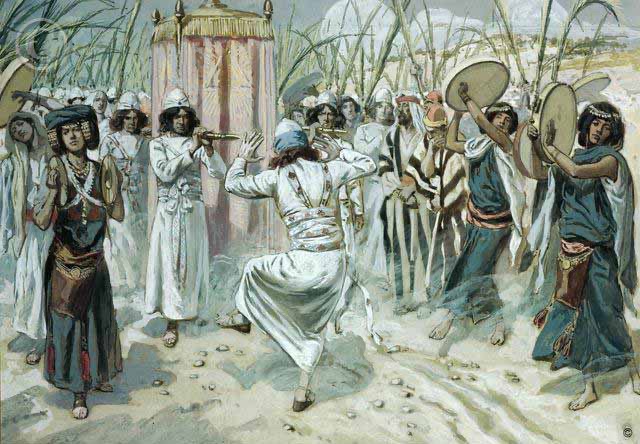

However, the lectionary (as it is wont to do) omits some verses from the middle of this narrative (6:6–11), as well as the closing section of the chapter (6:20–26). The middle section (6:6–11) reports the death of Uzzah, one of the sons of Abinadab, because he touched the holy ark with his hand. Before this omitted account is the report of David, with “all the house of Israel”, vigorously dancing “with all their might” as he led the Ark into the city (6:1–5), “with songs and lyres and harps and tambourines and castanets and cymbals” (6:5b). After the omitted verses we find David, continuing to dance “with all his might”, offering sacrifices to the Lord God and distributing food to the people in celebration (6:12–19).

Michael Brown, writing in With Love to the World, continues his reflections on this story: “The celebrations ended abruptly. This story of Uzzah’s death by touching the ark—with the best of intentions to steady it as the oxen stumbled—may be strange to us. Yet it is told as a reminder that it is not within anyone’s power to control, guide or steady the divinity to whom the sacred symbols point. Rather, it is we who are guided, steadied or even shaken by the sacred. David, shaken to the core, angry and afraid, stopped the procession in its tracks and left the ark at a nearby house for three months. An awe-filled experience of the sacred may be a chance to pause and recalibrate.”

The death of Uzzah occurs because of the holiness of the ark, as the dwelling place of God. Touching it directly—breaching the boundary between the holy and the everyday—would be enough to incur death. “God struck him there because he reached out his hand to the ark”, the text advises (2 Sam 6:7); this contravenes the earlier instruction of the Lord to Moses, “you shall put the poles into the rings on the sides of the ark, by which to carry the ark; the poles shall remain in the rings of the ark; they shall not be taken from it” (Exod 25:14–15).

The holiness of the Ark is evident in the set of directions regarding the Tabernacle (from Exod 25 onwards), when Moses had been instructed, “you shall put the mercy seat on the ark of the covenant in the most holy place” (Exod 26:34). Likewise, decades after David, as Solomon dedicates the Temple, “the priests brought the ark of the covenant of the Lord to its place, in the inner sanctuary of the house, in the most holy place, underneath the wings of the cherubim” (1 Ki 8:6; also 2 Chron 5:5–7; and see Heb 9:1–5).

The way that David welcomed the ark into the city underlines the reverence and awe that was due towards God. A wonderful festival is held. From that time onwards, the ark remains in Zion, where the Temple is the focus of piety. Another transition has taken place, from a holy artefact that was mobile, to a fixed, permanent house for God. Now “the most holy place” of the mobile Tabernacle (Exod 26:33–34; 1 Chron 6:49) would be come “the most holy place” of the temple (1 Ki 6:16; 7:50; 8:6; 2 Chron 3:8–10), or “the Holy of Holies” (as it is labelled in Heb 9:3).

Holiness was certainly central to the religious and social life of ancient Israel. Those who ministered to God within the Temple, as priests, were to be especially concerned about holiness in their daily life and their regular activities in the Temple (Exod 28—29; Lev 8–9). The priests oversaw the implementation of the Holiness Code, a large section of Leviticus (chapters 17—26), which explained the various applications of the word to Israel, that “you shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy” (Lev 19:2; also 20:7,26).

As well as overseeing the various offerings and sacrifices that were to be brought to the Temple, the priests provided guidance and interpretation in many matters of daily life, including sexual relationships and bodily illnesses, as well as the annual festivals and other ritual practices.

In the towns and villages of Israel, by contrast, the scribes and Pharisees provided guidance in the interpretation of Torah and in the application of Torah to ensure that holiness was observed in daily living. They undertook the highly significant task of showing how the Torah was relevant to the daily life of Jewish people. It was possible, they argued, to live as God’s holy people at every point of one’s life, quite apart from any pilgrimages made to the Temple in Jerusalem.

Flowing on into the time of Jesus, we see that the followers of Jesus are instructed to consider themselves as God’s holy people (1 Cor 3:17; 6:19; Eph 5:25–27; Col 1:22; 3:12; Heb 3:1; 1 Pet 1:13–16; 2:5, 9) and to live accordingly. Holiness continues to be central in the Jesus movement—albeit, in the manner in which it has been redefined by Jesus (Mark 7:18–23; Matt 15:17–20).

James J. Tissot, David Dances before the Ark (1896–1902),

gouache on board, The Jewish Museum, New York

The lectionary also omits the report of what Michal, the wife of David, said and did as she witnessed this spectacle (6:20–23). It includes the observation that, as Michal look at what David was doing, “she despised him in her heart” (6:16). This is a striking contrast to the earlier affirmation that “Michal loved David” (1 Sam 18:20, 28) and to the care that Michal took to save David from her father, Saul (1 Sam 19:8–17).

Michal is clearly offended that David was “uncovering himself today before the eyes of his servants’ maids, as any vulgar fellow might shamelessly uncover himself” (2 Sam 6:20), even though the earlier report had simply noted that “David was girded with a linen ephod” (6:14). We also don’t read the sad note that concludes this chapter, that “Michal the daughter of Saul had no child to the day of her death” (2 Sam 6:23). The alienation between the two seems complete; we hear nothing more of Michal in the later chapters of 2 Samuel, nor in the book of Chronicles.

Writing in the Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, Dr. Tamar Kadari notes that later Rabbis proposed that “she had no children until her dying day, but on her dying day she bore a son. The midrash speaks of three women who had difficult deliveries and died in childbirth: Rachel, the wife of Phinehas, and Michal daughter of Saul. Michal bleated like a sheep when giving birth and died, and therefore she was called “Eglah” (Gen. Rabbah 82:7).” (The Hebrew word eglah means “heifer”.) This midrash links Michal with “the wife of David” mentioned at 2 Sam 3:5 and 1 Chron 3:3, who was the mother of Ithraem.

Kadari also notes that Rabbis in a later time—when the Talmud was finalised in the fifth or sixth century CE—elevated Michal in status, noting that they comment that “this righteous woman that Michal would put on tefillinn every day, and the sages of the time did not protest, even though there is no halakhah requirement for a woman to do so (JT Eruvin 10:1, 26a).”

In an article in the online Biblical Theology Bulletin: Journal of Bible and Culture (vol.51 no.1, 2021), David. J. Zucker explores “Four Women in Samuel Confront Power”. He alert us to the stories of four occasions in the books of 1–2 Samuel when “women put their lives at risk as they dare to confront power … Abigail of Maon to rebellious David; the Medium of Endor to King Saul; the Wise Woman of Tekoa to King David; and the Wise Woman of Abel to Joab, King David’s general.”

Sadly, none of the stories relating to these women are included in the passages suggested by the Revised Common Lectionary. As is often the case, the focus is on the men in the narratives proposed.

Zucker notes that “The details surrounding their specific situations differ considerably from case to case. Likewise, from what little the Bible tells about their backgrounds, it is likely that they all came from different social classes. Nonetheless, each example fits within a broad definition of speaking truth to power.”

See https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0146107920980931?

The four women dealt with by Zucker are Abigail of Maon, the wife of Nabal (1 Samuel 25); the Medium of Endor (1 Samuel 28); the Wise Woman of Tekoa (2 Samuel 14); and the Wise Woman of Abel (2 Samuel 20). None of these chapters are included in the sequence of lectionary offerings. Zucker explains how these women speak truth to power.

“Abigail of Maon interacts with pre-monarchic David, then a rebel on the run since he is distanced from King Saul. The Medium of Endor is visited by King Saul, who is seeking Divine counsel via the recently deceased prophet Samuel. The Tekoite has come to King David ostensibly to seek resolution to her family’s blood vengeance problem. The Abelite representing her community which is threatened with immediate destruction is in dialogue with Joab, King David’s foremost general.”

He notes that “these stories vividly capture some of the very different ways in which women in the [Hebrew Bible] are resisting the violence of war that has the potential to utterly destroy their families and the communities in which they live.” What a pity we are not offered the opportunity to consider them in what we read in public worship.

*****

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.

You can subscribe on your phone or iPad via an App, for a subscription of $28 per year. Search for With Love to the World on the App Store, or UCA—With Love to the World on Google Play. For the hard copy resource, for just $28 for a year’s subscription, email Trevor at wlwuca@bigpond.com or phone +61 (2) 9747-1369.