“The angel of the Lord appeared to [Moses] in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed. Then Moses said, ‘I must turn aside and look at this great sight’ … and [when] the Lord saw that he had turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, ‘Moses, Moses!’ And he said, ‘Here I am.’ Then he said, ‘Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.’” (Exod 3:2–5)

The story of the burning bush is well-known; it is the moment when Moses, the murderer who has fled from Egypt (2:11–15), is galvanised by a striking event to become Moses the liberator, the one who will “go [back] to Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt” (3:10). The transformation is striking—although perhaps the transformation is not quite as dramatic as many envisage.

It may well be the case for Moses that a strong sense of justice undergirds both his act of killing the Egyptian who was beating a Hebrew (2:11), and his commitment to deliver the Israelites from “the misery of Egypt” (3:17). Moses was passionate about the need for justice in society. Paradoxically, this passion led him to say NO to a man he witnessed committing a crime, and YES to a body of people who were suffering oppression in a foreign land.

Of course, common sense says that Moses should not have taken things into his own hands when he saw that Egyptian man beating one of his fellow-Israelites. But the passion within him—passion for fairness and justice—boiled up inside him and overflowed into unjust actions. This was in keeping with the charge given to the father of his people, when God mused about Abraham, “I have chosen him, that he may charge his children and his household after him to keep the way of the Lord by doing righteousness and justice” (Gen 18:19).

No wonder Moses fled, escaping the wrath of Pharaoh, travelling east across the desert areas of the Sinai Peninsula, all the way to Midian! (Exod 2:15). His action, out of proportion with the crime he saw being committed, was unjust. It is not a very propitious start for Moses, the man who towers over the story of the people,of Israel—ironically, best remembered as Moses the lawgiver!

Mind you, throughout Genesis, we have been regaled by tales of men behaving badly—Abraham lying about his wife Sarah as his sister (Gen 12 and again in Gen 20) and threatening to sacrifice his own son (Gen 22); Isaac, who also lied that his wife Rebekah was his sister (Gen 26); and Jacob, the deceiver, who stole his birthright from his twin brother Esau (Gen 27) and then deceived his father-in-law Laban and profited from his flock (Gen 30–31). And let’s not go into the treatment of Joseph by his brothers, throwing him into a pit in the desert, and then selling him off to some passing Midianite traders (Gen 37). And there are more; they are not exactly wonderful role models!

Yet the story about Moses that we are offered by the Narrative Lectionary this week presents Moses in a much more positive light, and it contains two fundamental elements in the story of Israel: the declaration that Moses stands on holy ground, and the revelation of the name of God.

Holy ground

God’s word to Moses, after calling for his attention, is to declare that “the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (Exod 3:5). This is the first occurrence of the concept of holiness in the Torah—the word is absent from all of the narratives in Genesis. And it is fascinating that this “holy ground” is in Midian, both far away from Egypt and far away from Canaan, the land that would subsequently be decreed as holy (Exod 15:13; Jer 21:23; Zech 2:12). This God is now able to appear in places far away from Canaan, and declare them holy.

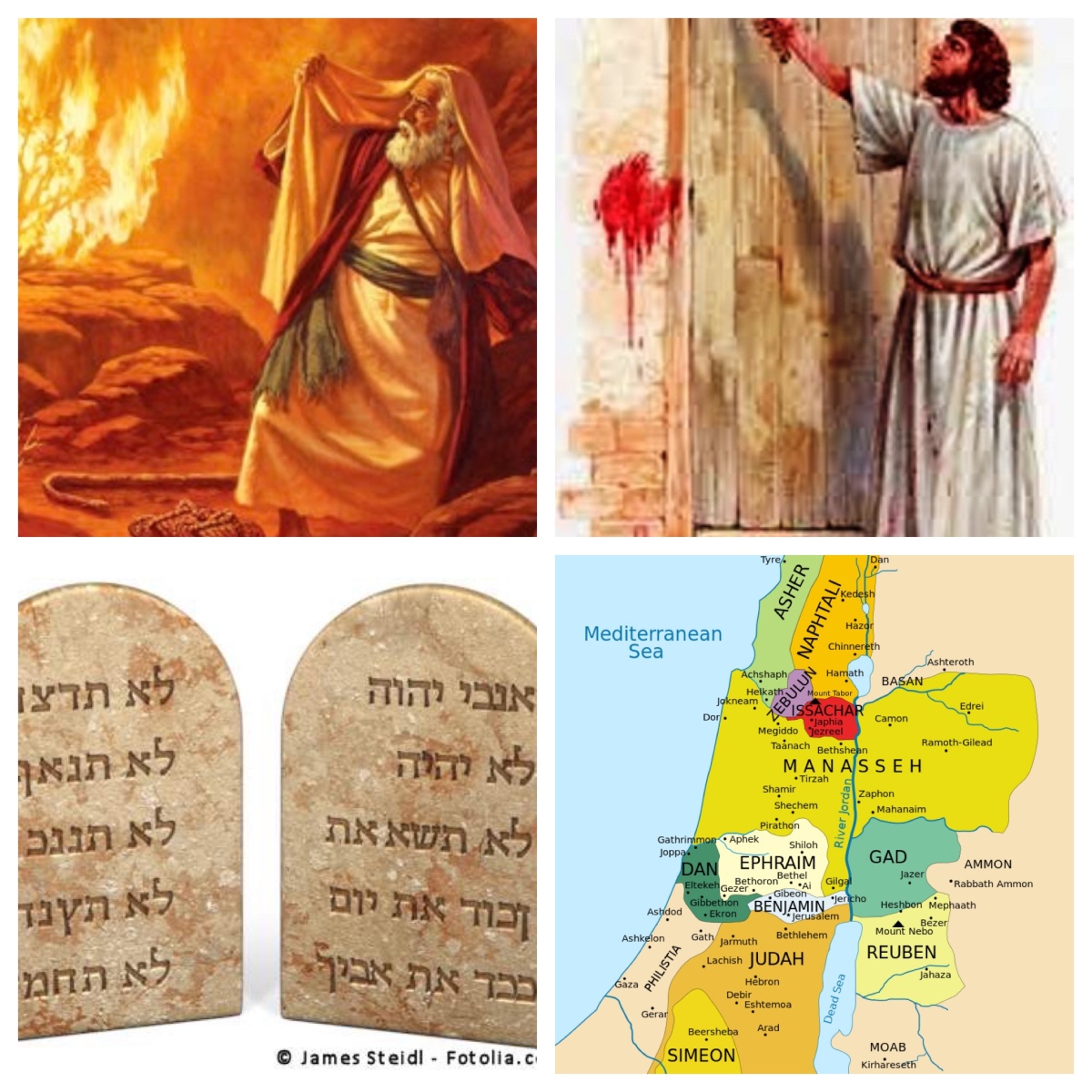

A central motif in Hebrew Scripture is that holiness was a defining character of the people of Israel. A section of Leviticus (chapters 17—26) is known as “The Holiness Code”; its main purpose was to set out laws to mark Israel as different from the surrounding cultures. “You shall not do as they do in the land of Egypt, where you lived”, God told Moses, “and you shall not do as they do in the land of Canaan, to which I am bringing you” (Lev 18:2).

The rules of Leviticus were meant to set the Israelites apart from the Canaanites and Egyptians, who at that time had customs and rituals that were not to be adopted by the Israelites. Moses is instructed to relay to the people, “you shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy” (Lev 19:2), and to remind them to “consecrate yourselves therefore, and be holy; for I am the Lord your God. Keep my statutes, and observe them; I am the Lord; I sanctify you” (Lev 20:7). The whole book details those many statutes and commandments, all designed to keep the practices of the Israelites “holy to the Lord” (Lev 19:8; 23:20; 27:14–24).

Once the Temple was constructed, as a holy place within that holy land, those who ministered to God within the Temple, as priests, were to be especially concerned about holiness, both in their daily life and in their regular activities in the Temple (Exod 28–29; Lev 8–9). The priests oversaw the implementation of the Holiness Code, explaining the various applications of the word to Israel, that “you shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy” (Lev 19:2; also 20:7, 26).

In the years before and during the exile, a number of prophets took to addressing the Lord God as “the Holy One of Israel” (Hos 11:9, 12; Isa 1:4; 5:9, 24; 10:20; 12:6; 17:7; 29:19; 30:11–15; 31:1; 37:23; 41:14–20; 43:3, 14; 45:11; 47:4; 48:17; 49:7; 54:5–6; 60:9, 14; Jer 50:29; 51:5; Ezek 39:7; Hab 1:12; 3:3). The psalmists also pick up this phrase (Ps 71:22; 78:41; 89:18), reflecting the affirmation made by Hannah, “there is no Holy One like the Lord, no one besides you; there is no Rock like our God” (1 Sam 2:2).

As a consequence, Israel is regularly assured that the whole nation is a “chosen people” (Deut 7:6–8, 14:2; Ps 33:12; Isa 41:8–10, 65:9), set apart as “a kingdom of priests, a holy nation” (Exod 19:4–6), called to be “a light to the nations” (Isa 42:6, 49:6). So in the towns and villages of Israel, by contrast to the centralised priests, the scribes and Pharisees provided guidance in the interpretation of Torah and in the application of Torah to ensure that holiness was observed in daily living of all people in Israel.

These dispersed teachers undertook the highly significant task of showing how the Torah was relevant to the daily life of Jewish people. It was possible, they argued, to live as God’s holy people at every point of one’s life, quite apart from any pilgrimages made to the Temple in Jerusalem. These figures, scribes and Pharisees, are evident in a number of interactions with Jesus that are reported in the Gospels—interactions focussed on interpreting the Torah (Mark 7:1–23 and Matt 15:1–20 exemplify such encounters).

Perhaps the origins of this localised interpretive role are told in the post-Exilic narrative of Nehemiah, when “the priest Ezra brought the law before the assembly, both men and women and all who could hear with understanding”, ably assisted by men who “helped the people to understand the law, while the people remained in their places”, explaining the significance of “this holy day” and other matters (Neh 7:73b—8:12). The story explains the modus operandi of these teachers.

Certainly, the culture and religion of the Israelites was to be marked by a concern for holiness. This is read back into the foundational narrative of the call given to Moses, “to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt” (Exod 3:10, 17). When he hears this call in Midian, Moses is standing on holy ground (3:1-12).

Name of God

Although he is in Midian, far away from Canaan (later to become Israel), Moses encounters the God who is most firmly identified with that land. It is “the Lord, the God of your ancestors, the God of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Jacob” who appeared to Moses (Exod 3:6, 16). This is the first occurrence of this characteristic linkage of the Lord God with the three patriarchs (see also Exod 3:15–16; 4:5; 6:3, 8; 33:1; Lev 26:42; Num 32:11; Deut 1:8; 6:10; 9:5, 27; 29:13; 30:20; 34:4; 2 Ki 13:23; Jer 33:26).

Identified, therefore, as “the God of your ancestors” (in Hebrew, elohe abotekem) (3:15, 16; 4:5), a distinctive term is added into the mix, and highlighted by God as “my name forever … my title for all generations” (3:15). The term is regularly translated as Lord, and is often capitalised to indicate its distinctive nature. In fact, the name comprises just four consonants (transliterated as yhvh or yhwh).

Despite its apparent simplicity, the meaning of the word has occasioned intense discussion amongst interpreters over the centuries. First, we should note that many Jews today adhere to the age-old prohibition and do not speak the name of God. This is based on the third of the Ten Commandments, “You shall not take his name in vain” (Exod 20:7; Deut 5:11).

Rabbi Baruch Davidson, writing on the website chabad.org, explains: “Although this verse is classically interpreted as referring to a senseless oath using G‑d’s name, the avoidance of saying G‑d’s name extends to all expressions, except prayer and Torah study. In the words of Maimonides, the great Jewish codifier: ‘It is not only a false oath that is forbidden. Instead, it is forbidden to mention even one of the names designated for G‑d in vain, although one does not take an oath. For the verse commands us, saying: “To fear the glorious and awesome name. Included in fearing it is not to mention it in vain.’” See

The name of God that is given to Moses in this story is often referred to as the Tetragrammaton (meaning “four letters”), because it is a four-letter word, yud-hey-vav-hey (יהוה). This name is derived from the verb “to be”, which has led to speculation that it could be translated as “I am who I am” or “I will be whom I will be”—revealing nothing, really, about the nature of this divine being, other than the existence of God. It is a curious “revelation”. What has Moses actually learnt about God in this encounter??

Since Hebrew words are constructed with a set of consonants as the base, to which a variety of vowels can be added, this short word is often expanded to either Jehovah or Yahweh. The former places the vowels of the word Adonai (meaning “lord”) to form the artificial term Jehovah, a title that has been popularised by the Jehovah Witnesses. The latter is a more accurate rendition of the blending of these consonants with the vowels of the verb to be, hayah, forming Yahweh.

This name is certainly mysterious. What does it mean to say, “I am who I am”? or “I will be who I will be”? The mystery of each phrase invites the listener or reader to pause, ponder, and consider what is being conveyed. This is not a direct propositional statement, declaring a closed statement along the lines of, “God is love”, or “God is all-knowing”, or “God desires justice”, or other such statements. It is, rather, mystical, evocative, inviting, something that is invitational and encouraging exploration. Perhaps that, in itself, is enough of a basis for our considering as to who God is and what God desires?

Jewish mystical literature actually teaches that there are seventy names for God; and if you explore the biblical texts (the Torah), the developing rabbinic literature (Mishnah, Talmud, and Midrash) and then the proliferation of Jewish mystical terms, God is referred to by almost more names than can be counted.

Rabbi Stephen Carr Reuben asks “Why so many names, and why does God tell Moses that the name he knows God by is different from that of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob?” As he explores this question, he notes that “Every name reflects a quality in relation to human beings that each of us can choose to emulate in our own lives. Thus in Jewish mysticism, the ideal state is to be in harmony with the Divine by emulating the attributes reflected in the great diversity of divine names.”

The rabbi offers some examples: “As God is called, ‘The Compassionate One’ (HARAKHAMAN in Hebrew), so each of us can strive to be compassionate in our behavior toward others. As God is called EL SHADDAI (The Nurturer), so we can be nurturing of the dreams and longings of others. As God is called The Righteous Judge (DAYAN EMET), so we can express righteousness and stand up for justice in our lives.”

What, then, of the revelation to Moses? Rabbi Carr Reuben suggests that “when God tells Moses that he was known by a different name to the patriarchs, it is because every moment in history, and every challenge we face personally demands that we draw upon a different quality of holiness to emulate in our lives. We must choose the name of God that captures the essence of the attributes of Godliness that is appropriate to the moment, and up to the challenge of the day.” See

and also https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-tetragrammaton/