This blog relates to the parable in Luke 15 offered in the Narrative Lectionary this coming Sunday, Lent 3. It also appears in the Revised Common Lectionary for the following Sunday, Lent 4.

At the beginning of the season of Lent, some 26 days ago, we heard again of the time that Jesus spent in the wilderness. Sometimes, when I have been in a placement where I was responsible for leading worship each Sunday throughout Lent, I have shaped the weeks around the theme of a Wilderness Journey. As well as the Sunday services, there were offerings of Bible Study groups that meet each week, designed to focus, specifically, on aspects of that theme, Wilderness Journey. It is a good way—one way among many ways—to foster an intentional Lenten discipline.

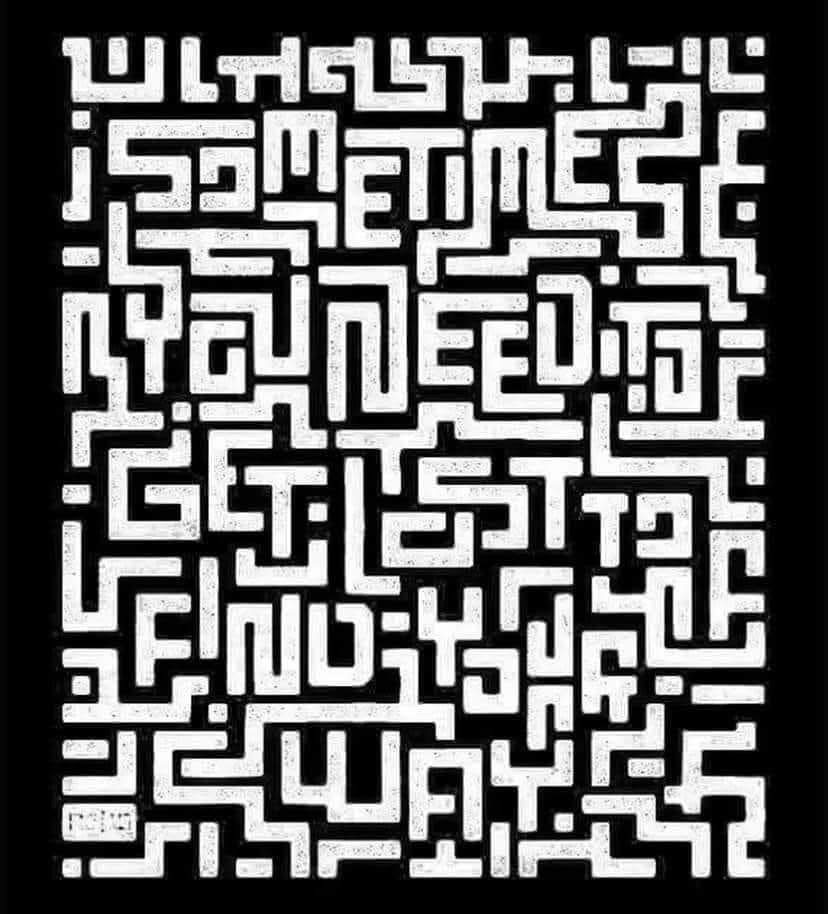

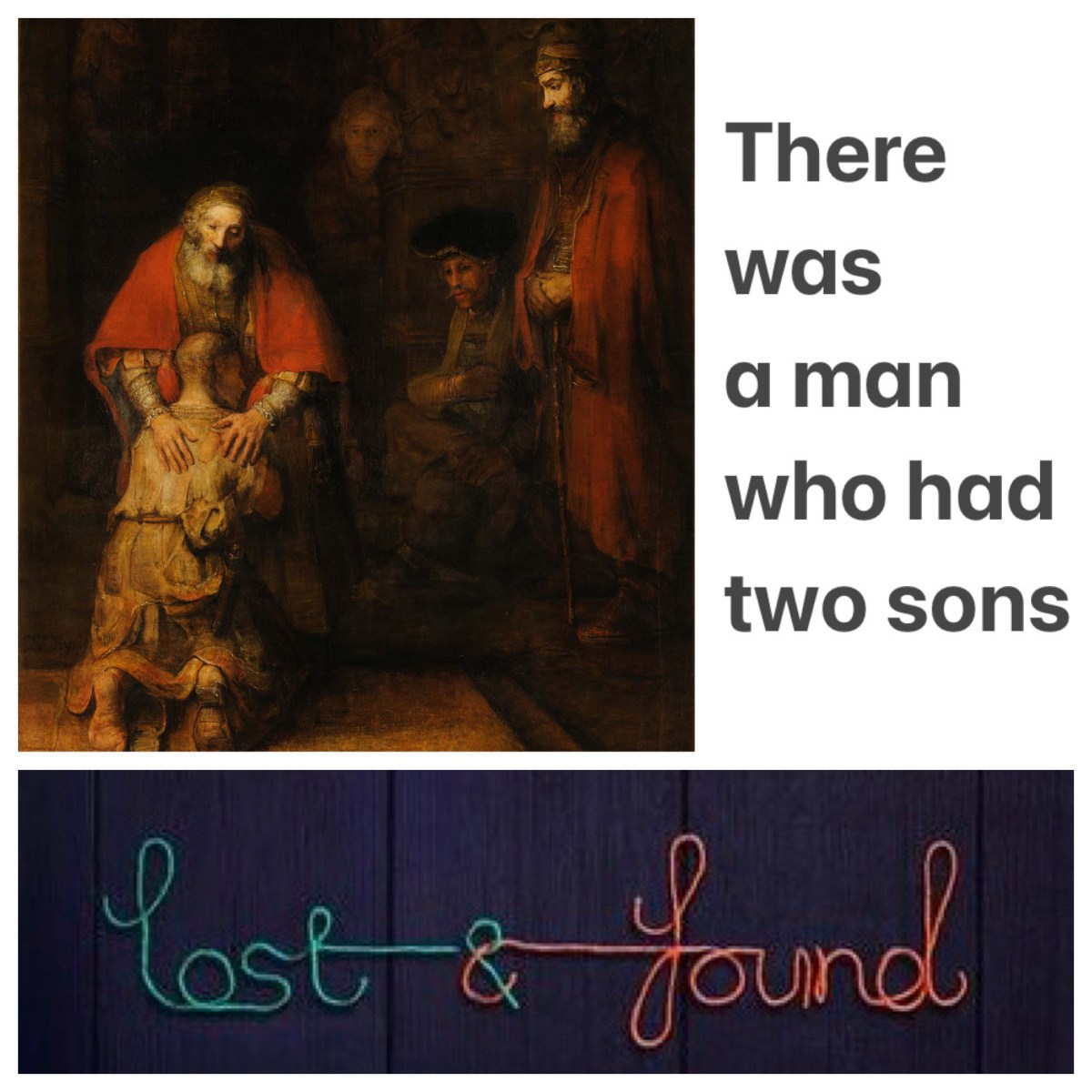

This theme continues, this coming Sunday, as the Gospel passage proposed by the lectionary invites us to consider the notion of being lost—an entirely understandable element in a Wilderness Journey! In this passage (Luke 15:11–32) we hear a much-loved and very familiar story. It’s a story about losing; but also about finding. About the wandering away of a much loved son; but also about the wondrous returning home of that once-was-lost son.

Often, taking this particular focus of “the one who was lost is now found” (v.24), this story is called The Parable of the Prodigal Son. (The adjective “prodigal” seeks to capture the “dissolute living” on the younger son, as described in vv.13–16.) The focus is on the character regarded as central—the younger of the two sons, whose decisions in life are seen to reflect the innate human sinfulness that a dominant stream in orthodox theology has attributed to all human beings. The younger son is a symbol for every one of us.

However, this is a story that has more than one character in it; more than just this one “prodigal son” who so often gives his name to the parable. Sometimes, I wonder whether it might be better to rename The Parable of the Prodigal Son, and call it The Parable of the Two Prodigal Sons, recovering the emphasis on both sons in the latter part of the parable.Or perhaps, The Parable of the Gracious Father, reorienting the focus to the acts of kindness and compassion displayed by the father as he welcomes one son back home. How would you name it?

Of course, this parable sits in a chapter where there are three stories in a row, focussed on the same dynamic: what was once lost, is now found. The sheep, once lost, now found (v.6). The coin, once lost, now found (v.9). And the son, once lost, now found (v.24). Or, is that, the two sons, each lost: one, a runaway who came to his senses and returned; the other, a stay-at-home that came to his senses without ever having to leave home (v.32). In each case, joy is the central motif of the parable that is told (vv.7, 10, 32).

Whatever you call it, this parable is a story that invites us to reflect on our own journeys. In those journeys, there are moments of being lost, as well as moments of being found, within our own lives. Moments when we ventured afar; moments when we realise that we are lost; moments when we set out back home to be with the family; and (hopefully) moments of joyful reconciliation on our return.

Can you remember a time when you wandered off from your faith? And a time when you returned to the community of faith? Perhaps a time when you felt alone, rejected, sitting in poverty in the midst of a pen of swine, as it were? Or perhaps the time when you were met by the loving embrace and joyous celebration of the community, rejoicing as you returned into the family, to share in the feast that had been prepared?

This parable invites us to think about the experiences of losing, and finding—or being found—not only within our own lives, but also within this community of faith. Think about the community of faith to which you belong. What have you lost as a community, together? And what have you found, together, in that community? Found, for the very first time—or perhaps a rediscovery of something that was once lovingly held?

A little while ago I ministered for an agreed period of time (12 months) as an Intentional Interim Minister (IIM). It was a community which had been through a process of loss. I knew that, within such a community, a group of people gathered around a common cause, there would be many who have felt the experience of loss quite acutely. But there would also have been some for whom the loss was less-intensely felt. The experiences of loss felt by individuals would be quite varied. That is certainly what I encountered in the particular community where I was ministering.

Some had experienced the loss of a beloved and respected minister. Their thinking was along the lines of “We had an opportunity to move in new directions, but we haven’t done so. We had the experience of many new people joining us to participate in our common life, but they have now gone. We were given different ways of understanding our faith, but that is no longer offered to us each Sunday. We have experienced loss”

Others, I found, had experienced loss in a different way: the disruptions of previous years had led, in their view, to a loss of a familiar pattern of worship, a familiar way of understanding God, a familiar set of practices and customs on a week-by-week basis. I suspect they were thinking: “We have lost a sense of reverence in church. We no longer have a large and flourishing youth group. We seem more oriented to doing particular works in our community, less oriented to praying and studying scripture together. We have experienced loss.”

But although there were different ways in which that loss was felt and understood, it was an experience held in common across virtually all the congregation. I spent some time encouraging people to name their loss, and to know that “if you are experiencing this sense of loss, you are not alone; you, and your neighbour, and the people who regularly sit on the other side of the church, are also experiencing that sense of loss. It may be in relation to different issues. But you are all experiencing loss.”

Bear with me. I will come (back) to the story of the gracious father and his two sons, for that is the focus of this post. But first, a little more theory.

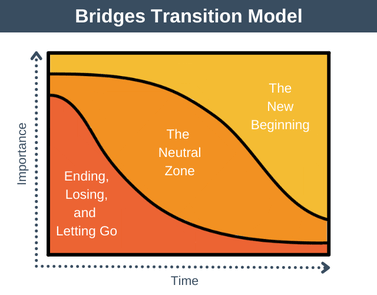

An important factor that helped to guide me in the situation in which I was ministering, a few years ago, was a theory was something known as Transition Theory. This had formed an integral part of the training I had received in preparation for serving as an Intentional Interim Minister (IIM); it was one plank in the foundation that undergirded the work I undertook with the people of the congregation in the transitional process that I guided them through during the course of the year.

The particular form of Transition Theory that I used was developed by William Bridges, in a book he wrote, entitled Managing Transitions (2009). In this book, Bridges talks about transitions in terms of three stages: first, there is the letting go; then there is the neutral zone of being in-between; and finally, the connection into a new place, a new way of being. In that neutral, in-between zone, there is a need for us to nurture and develop a capacity to live within the discomfort of ambiguity which arises during the experience of loss, as we move away from the familiar.

What Bridges calls the neutral zone, is actually akin to what appears in the biblical story, time and time again, as the wilderness. Moving through the neutral zone, is the journey that is undertaken through the wilderness. That is what Jesus did for those “forty days” in the wilderness, that we reflected on in the first Sunday of Lent. That is what the people of Israel had done for those “forty years” in the wilderness, which ended with the story told in Joshua 4, which is offered by the lectionary as the Hebrew Scripture passage for this coming Sunday, Lent 4.

In Hebrew, the word we translate as wilderness (midbar) means literally, “land uninhabited by humans”, or “land in between the places where human beings live”. It can be a dangerous, threatening place to be. Remember that when Jesus was tested in the wilderness, he was without human company, but the wild beasts were present with him in that wilderness.

(And let’s also note that the length of time—40 days, or 40 years—is not an exact chronological period. Rather, it reflects the ancient Israelite way of expressing “a long, long period of time” in each case. Jesus spent a long time in the wilderness. Israel had spent a heaps long time in the wilderness!)

Bridges proposes that, if we are able to sit within the neutral zone, the wilderness, and engage with the discomfort of ambiguity, then it need not be a threatening, dangerous place. If we engage with the wilderness constructively, as Jesus did when he was tested, then we can experience change and transition as a constructive and life-giving experience. If we can emerge from the wilderness with a plan and a hope for the future, as Israel did, that ambiguous place will have prepared us well. The wilderness can become a pivot away from the past, into the future. That is the best outcome of a process of transition.

If we are not able to sit within that zone of ambiguity, feeling completely dislocated and wanting to move out of that wilderness zone, then we will experience change and transition as threatening, disruptive, and even destructive. We will be stuck in the wilderness, moving neither forwards nor backwards, hankering for the past, yet unable to move on into the future. Or, worse, we will retreat back into the past, seeking security in familiarities which may not any longer be realities.

The Return of the Prodigal Son (1773)

by Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

So, then: back to the Gospel passage. How might this insight of a Bridges relates to the story told in the Parable which forms our Gospel reading for the week (Luke 15:11–32)? In the parable of the prodigal son—or should that be the parable of the two prodigal sons—or perhaps even the parable of the gracious father—there are a number of key, pivotal moments; moments where characters enter that neutral, in-between zone; the wilderness; moments that can well be described as having the discomfort of ambiguity for one or more of the characters involved.

The younger son, unhappy at home, launches out on his own—proud, confident, self-assured; yet perhaps he has some anxiety, some ambiguity, about what lies ahead for him? Some slight discomfort, perhaps.

The father, seeing his younger son departing, undoubtedly considers whether, or not, he will provide him with his share of the property; but this is a fleeting moment of ambiguity, a brief sense of discomfort, which he apparently readily resolves in the affirmative.

The younger son, some time later on, having run through all that he had been given and in the midst of a serious famine, looks at his impoverished state and considers: “am I doomed to this life of poverty, or do I put my tail between my legs, and return home in humility?” Uncertain, highly anxious, this is the place of deep discomfort in ambiguity. That is the wilderness experience.

The son decides to remove this discomfort, and resolve the ambiguity, by turning to head home. He wants to leave the wilderness behind. He does not know how he will be received when he returns. But he commits to the journey back home, and looks to transition into a new place, a new status.

The elder son is happy to stay at home, enjoying all the benefits … and yet, perhaps he is wondering, “what if I asked for my share of the property, like my brother did? Could I make it good out there in the big wide world?” More ambiguity, some measure of discomfort, for him.

But that bursts into full-on, large-scale ambiguity, and intense discomfort, at the moment he sees his brother returning. “What will I do? Should I be glad to see him? Will he be welcomed back? Will I be happy that he comes back into his privileges as a son, even though he has spent his inheritance? Or will he be put with the servants, accepted back, but put into his place? Will I be happy to have him back here, again? Will he be a son, or a servant?” In this moment, he feels with intensity the discomfort of ambiguity.

And the father, now consumed by the swirling, seething rush of hope, experiences his own moment of the discomfort of ambiguity: “should I ignore him? Should I rush to welcome him? Will he expect to return as a son? Could I simply offer him a role, here, as a servant? What should I do.” The discomfort of ambiguity. The in-between, uncertain and destabilising experience, of being in an emotional wilderness.

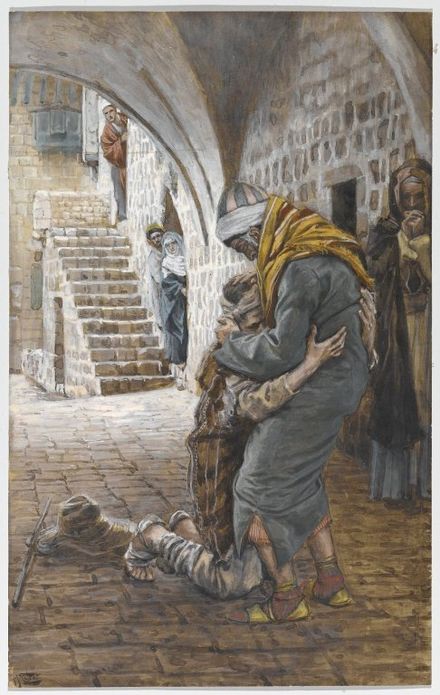

The Return of the Prodigal Son (Le retour de l’enfant prodigue)

by James Tissot (1836–1902)

And so the father runs, joyously, to greet his son. He remains in the zone of discomfort and ambiguity; there is no certainty about what will happen next; but he is able to step into the future, to rebuild his relationship with his son, because he has embraced the ambiguity and recognised the discomfort that he was feeling, as an opportunity to grow, change, and transform. The pressure of ambiguity is not completely resolved, but the father is able to move on with hope into this future. He is stepping out of the wilderness, into the future.

Accepting and valuing the ambiguity is a key element in the transition into the future zone. It is the key as to how we move on in our wilderness journey.

And yet, at this moment, the discomfort intensifies for the older son. “Now that my brother is back, I cannot abide this. Stand firm. Stay put. Do not greet him, do not celebrate with him, let them have their fatted calf without me!” And surely there is ambiguity, discomforting ambiguity, in this moment, for him? The future is uncertain. What will it hold? What will his relationship be with his brother? What will it be with his father? The ambiguity remains. The parable ends with the elder son still caught, discomforted, in the wilderness of uncertainty and ambiguity.

This is a story of being lost, and being found. The parable contains a sense of discomfort in multiple moments of decision. The ambiguity of belonging, detaching, reconnecting; farewelling, welcoming, reconnecting; deciding.

We all face moments that are filled with the discomfort of ambiguity. William Bridges, as I have noted, writes about the capacity that we each have—and that we need to nurture and develop—the capacity to live within the discomfort of ambiguity. We need to embrace the wilderness. We cannot escape it by running away. We need to explore our wilderness experience to the fullest.

If we stay within the wilderness, the zone of ambiguity, then we can experience change and transition as a constructive and life-giving experience. If we are not able to sit within that zone of ambiguity, and are always wanting to move out of that zone, then we will experience change and transition as threatening, disruptive, and even destructive.

The Return of the Prodigal Son (1662–1669)

by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669)

I am left with many questions from this parable of Jesus. How might we move through our own sense of being lost, in whatever way that is manifesting, to the assurance of being found? What steps do we need to take? Whose path are we following in this process?—the younger son, or the older son?

How can we take our steps towards the God who runs to meet us, “filled with compassion ([who] puts his arms around [us] and kisses [us] … [and cries out] bring out a robe—the best one—and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet; and get the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate; for this [child] of mine was dead and is alive again; [they were] lost and is [now] found!”?

*****

I close with a prayer for the week, from the mystic, Thomas Merton, which appears on a regular cycle in my daily devotions (with the Northumbria Community), and which is pertinent to these reflections.

My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going.

I do not see the road ahead of me.

I cannot know for certain where it will end.

Nor do I really know myself,

and the fact that I think that I am following your will

does not mean that I am actually doing so.

But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you.

And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing.

I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire.

And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road,

though I may know nothing about it.

Therefore will I trust you always,

though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death.

I will not fear, for you are ever with me,

and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.

— Thomas Merton, 1958