The story of Pentecost is told in Acts 2. It is a central Christian festival. Here are ten things that I reckon we should know about Pentecost.

One. Pentecost was originally a Jewish festival. It was one of the “great three festivals” that took place each year in ancient Israel: Pesach (meaning Passover), the feast of the Unleavened Bread; Shavuot (Weeks or Pentecost), the feast of the first harvest of the grain (wheat); and Sukkot (Tabernacles, Tents or Booths), the festival of ingathering which marked the end of the harvest season. These three occasions are identified as recurring annual festivals at Exodus 23:14-17 and again at Deuteronomy 16:16-17.

Two. Pentecost means “fiftieth”. In Judaism, it is the 50th day since the feast of Passover (see Leviticus 23:15-16). In Christianity, it becomes the 50th day since Easter Sunday. The significance of 50 is that it the day that comes after seven weeks (that is, 7 X 7 days = 49 days). So it is a perfect “week of weeks”.

Three. Pentecost symbolises two key things in Judaism. The prescriptions for Shavuot, the festival of Pentecost, are set out in the Hebrew Bible. Exodus 34:22 states that it marks the all-important wheat harvest in Israel; Leviticus 23:15-22 sets out the requirements for celebrating this festival. Its importance as an agricultural festival is thus clear. Alongside that, as Jewish tradition developed, Pentecost became the anniversary of the giving of the Law; the day when God gave the Torah (the Law) to the whole nation of Israel, assembled at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19:1–20:21).

Four. The people gathered in Jerusalem for Pentecost when the spirit came were all Jews. Acts 2:5 makes this clear; those present were devout Jews from every nation under heaven living in Jerusalem. They were not Gentiles. Luke and Acts persistently make it crystal clear that the Gospel was intended for the whole world—Jews and Gentiles alike (Luke 2:30-32, 3:6, 24:47; Acts 1:8, 2:17, 9:15, 10:34-43, 11:18, 13:47, 14:27, 15:7, 22:21, 26:17-23, 28:28). Nevertheless, this event is one that gathers only Jews.

However ….

Five. Acts 2 does symbolise that the Gospel is for all the world. The people noted in Acts 2 were Jews who had come from every nation, spread right across the ancient Mediterranean world. In this sense, they represented the Gentiles, as, even though they were Jews, they were living in the Dispersion, amongst Gentiles, and they came from those nations that were predominantly Gentile. These faithful Jews had gathered in Jerusalem because it was the place where the Temple was based; it was the centre of Jewish faith.

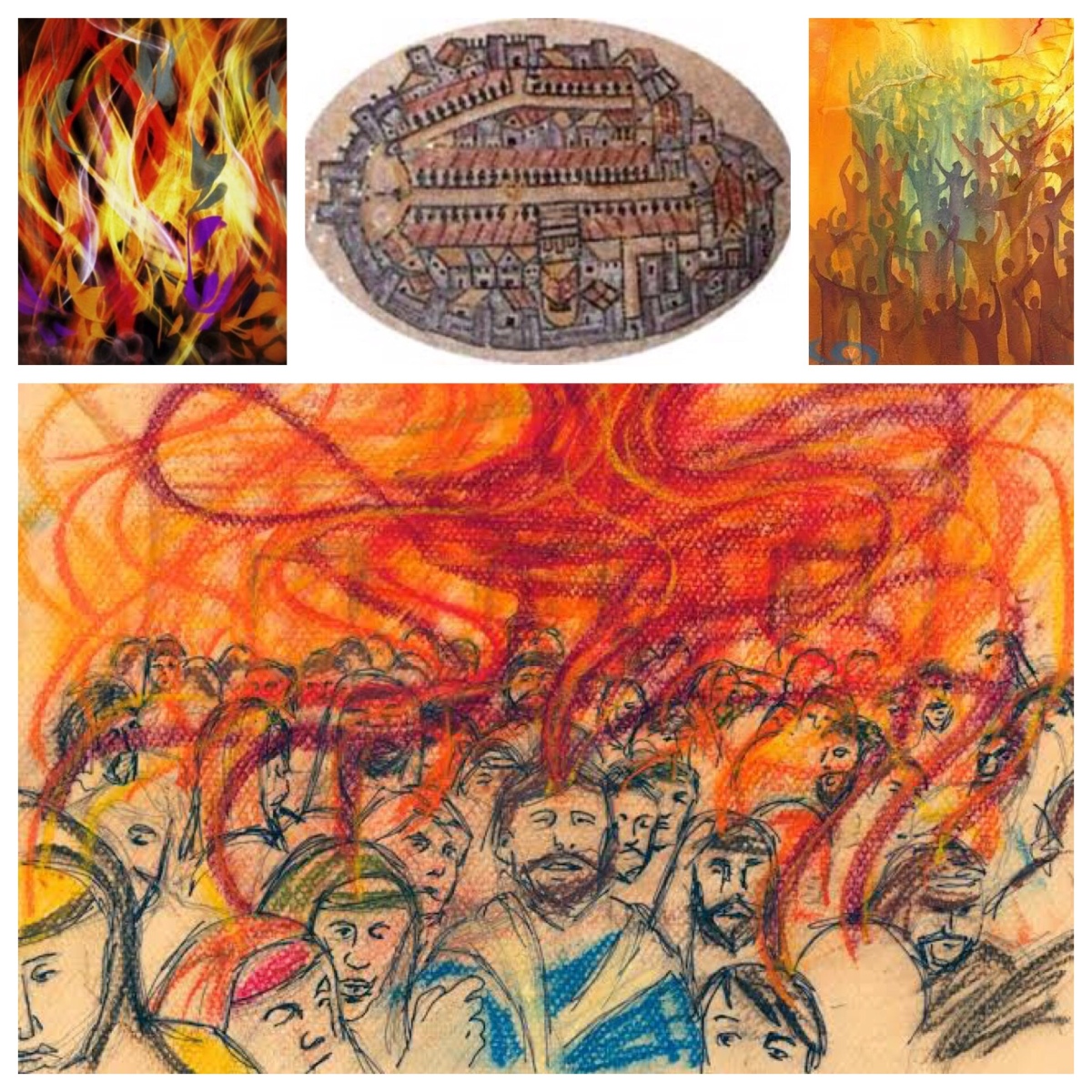

But more than this, Jerusalem was also considered to be the centre of the world, according to ancient Jewish traditions. Jewish maps from long ago through into the early medieval period regularly locate Jerusalem at the centre, and show the nations spreading out from it in all directions.

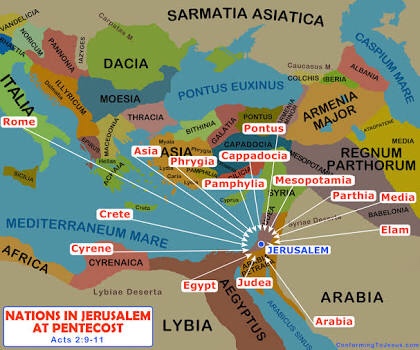

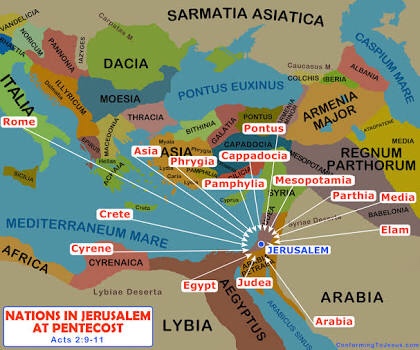

So, in Acts 2, Jews come from the east (Parthians, Medes, Elamites, residents of Mesopotamia), north (Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia), west (Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, and Cretans) and south (Arabs). This map gives an indication of how this works:

Indeed, it could well be that, for the author of Acts, this scene provides a fulfilment of the eschatological prophecy about “the gathering of the nations” on Mount Zion (Isa 2:2-4, 11:12, 42:1-6, 62:1-2, 66:18-24).

Six. The Spirit acted at Pentecost; but this was not the first time that Jewish people had experienced the Spirit. Pentecost was far from being the first time that the Spirit came. Hebrew Scripture refers to the actions of the spirit at many places throughout the story of Israel: in the times of Joseph (Gen 41:38), Moses (Exod 35:30-31, Num 24:2, Neh 9:20), Joshua (Num 27:18, Deut 34:9), the Judges (Judg 3:10, 6:34, 9:23, 11:29, 13:25, 14:6,19, 15:14), Saul (1 Sam 10:6, 11:6, 19:23-24), David (1 Sam 16:13, 2 Sam 23:2), Isaiah (Isa 11:2), Ezekiel (Ezekiel 2:2, 3:12, 14, 24, etc) and later prophets (Micah 3:8, Haggai 2:5, Isa 42:1, 44:3, 59:21, 61:1).

In fact, later texts indicate that the spirit inhabits human beings simply through the fact that they exist as the creations of God (Job 27:3, 32:18, 33:4, Zech 12:1), and all of creation came into being through the spirit of God (Psalm 104:30). Indeed, the post-exilic priestly document that incorporated the foundational creation myth of the peoples explicitly noted that it was by the spirit of God that the creation came into being (Genesis 1:1-3). The Holy Spirit was already integral to the faith of the ancient Israelites.

See https://johntsquires.com/2021/05/19/pentecost-the-spirit-and-the-people-of-god-acts-2-pentecost-b/

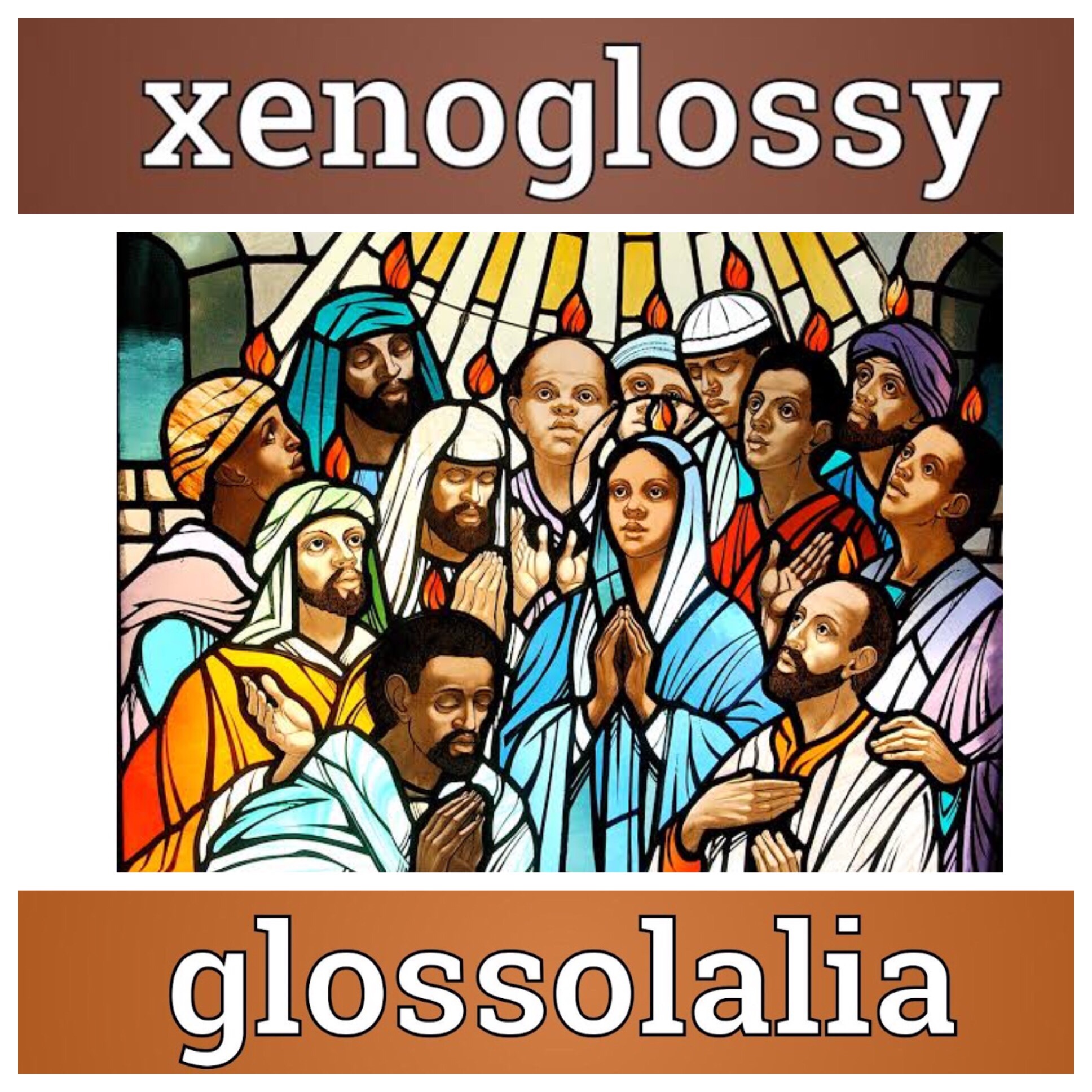

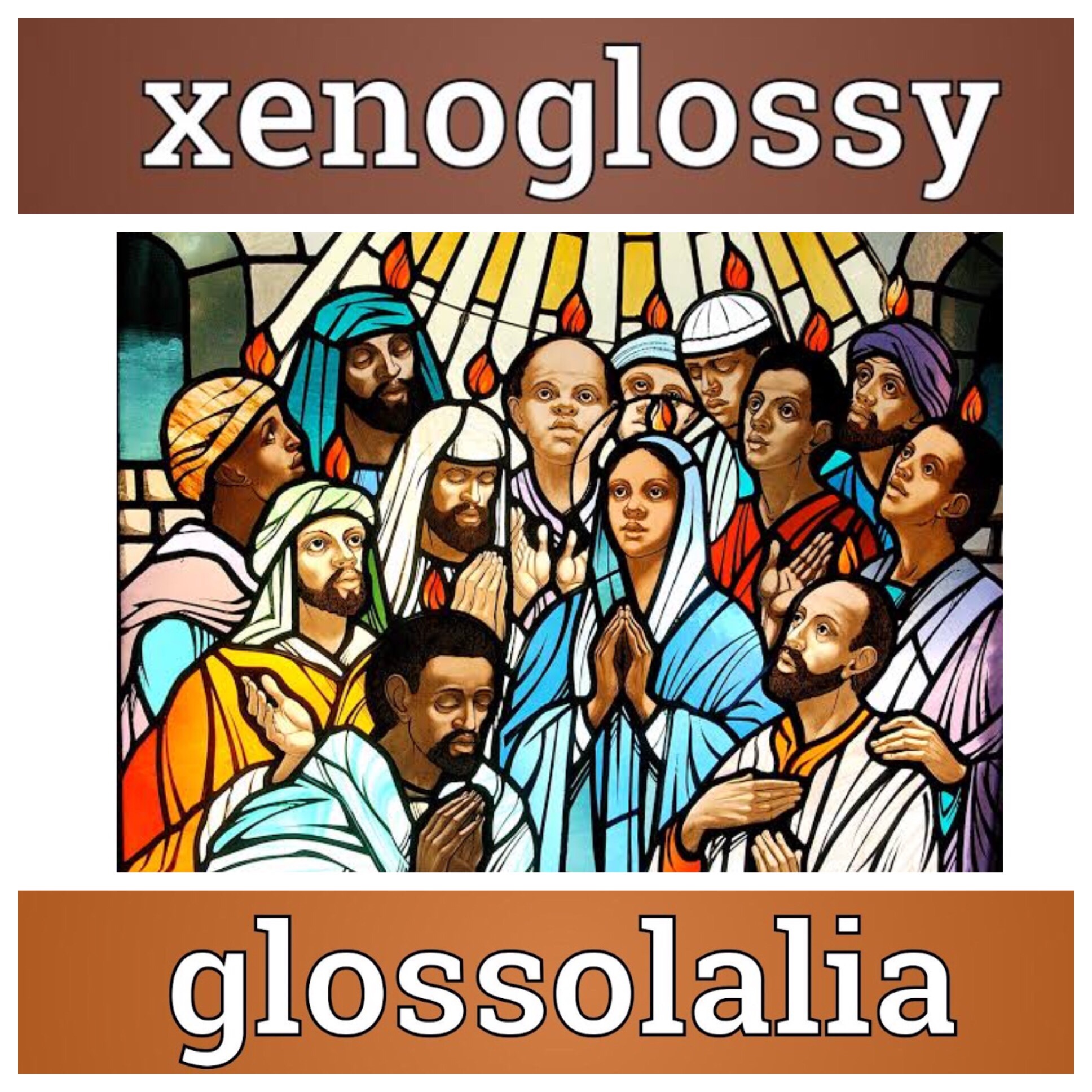

Seven. The mass of noise that occurred at Pentecost was not “speaking in tongues” as can be experienced in modern-day Pentecostal or charismatic churches. The noises made were not the kinds of “speaking in tongues” that Paul refers to in 1 Cor 12–14. Rather, the author of Acts makes it very clear that these are real, actual, specific languages. Acts 2:5-11 specifies that this was xenoglossia, that is, known foreign languages, whereas Paul uses the term glossolalia, meaning setting the tongue free to make sounds most likely unintelligible to the hearer, but pleasing to the speaker.

It is clear from the account in Acts 2: people in the crowd plainly affirm that they are hearing the Galilean followers of Jesus speaking fluently in their own native languages from the many different places they have come from (2:8), before going on to spell out the precise languages they heard (2:9-11).

So, there is no mandate in this passage for claiming that true believers MUST “speak in tongues”. For the author of Acts, it is most likely that this phenomenon begins to fulfil the prophecy of Jesus about his message being proclaimed to every nation; those gathered in Jerusalem hear and understand the message of salvation in their own tongue, within their own culture, in their own context. This is a story about the universal scope of the message about Jesus.

Eight. The sermon that is reported in Acts 2 is not a verbatim account of an actual sermon. It is an “educated guess” made by the author of Acts, in the light of what he knew about the preaching of the apostles in the decades between the life of Jesus and when he was writing down his “orderly account”.

In doing this, the author was following the pattern adopted by Greeks who had written histories in previous times, in accord with the guidelines that the historian Thucydides set out: “I have found it difficult to retain a memory of the precise words which I had heard spoken; and so it was with those who brought me reports. But I have made the persons say what it seemed to me most opportune for them to say in view of each situation; at the same time, I have adhered as closely as possible to the general sense of what was actually said.”

It is widely recognised by scholars that this means that Thucydides, and those following him, provided words appropriate to the occasion that they composed themselves, rather than actual reports of real speeches.

And, of course, Luke was not there on the day of Pentecost when Peter preached to the crowd. So it is highly likely that “Luke” follows the tradition that had been in effect since the time of Thucydides. Indeed, there are a number of the conventions from Hellenistic rhetoric of the time which can be seen in this speech, which thereby contains clear indications that it has been constructed and shaped by a well-educated, rhetorically-sophisticated person, such as “Luke”.

This was not an account of an actual speech given on a specific occasion. The speech which “Luke” attributes to Peter sets out what the apostles were preaching in the early decades after the death and resurrection of Jesus. This is a typical speech, or a synthesis of early apostolic preaching as the author of Acts knew it. It was included in Acts to provide the first century church with a template for faithful preaching of the Gospel.

Nine. Pentecost is not prescriptive for life in the church. We do not have to follow the sequence of events that is found in Acts 2 in a way is absolutely and precisely prescriptive. The baptisms that took place after the sermon had ended do not set the required pattern for baptisms in following decades and centuries. It is not necessary for belief to precede baptism by water and then by the Spirit! And then for “speaking in tongues” to take place. We cannot argue that the effect of baptism MUST be seen in the evidence of “speaking in tongues”.

In fact, if you look at how these various elements are reported throughout Acts, you will find quite some variances in order. There are stories about spirit, baptism, and belief, in Samaria, Acts 8, in Caesarea, Acts 10, and in Ephesus, Acts 18. The order and pattern of events is different in each case.

Ten. The purpose of the narrative that we have in Acts 2 is to offer a paradigm for the life of the church. The Acts 2 narrative is packed with details which are of importance for the whole narrative of Acts—and for the way the church is to function in the ensuing centuries. The author of Acts is telling us, through this dramatic narrative, how the church should seek to live.

The story indicates how the message of salvation (2:21, 2:40, 2:47) is to be proclaimed in the witness of preaching the message of salvation (2:14-36), attested in signs and wonders showing the presence of God (2:4-12, 17-20) and enacted in the regular routines of the community of faith (2:41-47; and see also 4:32-35).

The narrative of Acts 2 thus describes the stimulus to create a renewed faith community of those who were following The Way (9:2, 18:25), who were later called Christianoi (Acts 11:26). And so, the Day of Pentecost is rightly called The Birthday of the Church.

And a bonus point: Pentecost (the birth of the Church) is really the third great festival for Christians, alongside Christmas (the birth of Jesus) and Easter (the death and resurrection of Jesus). However, unlike the other two festivals, Pentecost remains untainted by contemporary secular practices. There is no feasting and drinking, no giving of many presents and no jolly rotund old man in a red suit (as at Christmas), and no four-day public holiday enticing people to head for the hills, or the beaches (as at Easter).

So we ought to rejoice in Pentecost, as the festival that we have, without overindulgence, excessive commercialisation, or holiday enticements, and simply enjoy it for what it is!

………

In this blog I have drawn from my own research into Acts and presented some key findings in summary form. My more detailed analysis is found in the commentary on Acts (pp.1217-1223) in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, ed. James Dunn and John Robertson (Eerdmans, 2003). See https://www.eerdmans.com/Products/3711/eerdmans-commentary-on-the-bible.aspx

See also https://johntsquires.com/2019/06/07/the-paraclete-in-john-15-exploring-the-array-of-translation-options/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/04/15/holy-week-the-week-leading-up-to-easter/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/04/18/easter-in-christian-tradition-and-its-relation-to-jewish-tradition/