The passage that is set forth by the lectionary for this Sunday (Mark 10:2–16) comes at a pivotal moment in the narrative that Mark narrates. For almost all of the nine chapters that have come before, Jesus has been in Galilee (see 1:14, 16–20, 28, 39; 3:7; 7:31; 9:30), including time in Capernaum (1:21; 2:1; 9:33) and Nazareth (6:1–6; Jesus was known as “Jesus of Nazareth”, see 1:9, 24; 10:47; 14:67; 16:6). Now he makes a decision to turn south and head to Jerusalem, the southern capital.

Mark makes a very bare geographical report: “he left that place and went to the region of Judea and beyond the Jordan” (Mark 10:1). Luke, at the equivalent place in his narrative, declares “when the days drew near for him to be taken up, he set his face to go to Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51). For Luke, this is a momentous turning point; he uses some weighty theological terms to mark the moment. When Jesus “set his face” to go to Jerusalem, he echoes the prophetic decision to pronounce judgement on Jerusalem (Isa 50:7; Jer 21:10; Ezek 4:3, 7; 6:2; 13:17; 14:8; 15:7; 20:46; 21:2; 25:2; 28:21; 29:2; 35:2; 38:2).

By noting that “the days drew near”, Luke uses a verb (symplērousthai) found also at Acts 2:1, to announce the coming of the Spirit at Pentecost. And the days that were drawing near were when he was “to be taken up”, looking ahead to the ascension (analēmpsin) which concludes Luke’s first volume (Luke 25:50–53) and opens his second volume (Acts 1:6–11).

All of that is missing from the simple geographical comment of Mark 10:1. In this Gospel, the significant theological weighting that is inherent in the turn to Jerusalem that Jesus undertakes is invested in the scene where he has his followers find a donkey, and he rides into the city to the acclaim of the crowd: “Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed is the coming kingdom of our ancestor David! Hosanna in the highest heaven!” (Mark 11:9–10).

Before that, however, Jesus has to deal, yet again, with some Pharisees (10:2). He had previously had debates with northern Pharisees in Galilee a number of times (2:15–17, 18–22, 23–28; 3:1–6; 7:1–13; 8:11–12). This time, amidst the crowds gathered to hear Jesus in “the region of Judea and beyond the Jordan”, some southern Pharisees now come “to test him” (10:2), as their brothers had done earlier (8:11)—the same dynamic that Mark had reported at the very start of the public activity of Jesus, when the Spirit cast him out into the wilderness “being tested by Satan” (1:12–13).

The test set by the Pharisees relates to the matter of divorce. They had a clear cut point of view about this, although in typical Pharisaic—rabbinic style they begin by posing a question. We have seen this technique before. “Why do John’s disciples and the disciples of the Pharisees fast, but your disciples do not fast?” they ask in Galilee (2:18); and then, “Look, why are they doing what is not lawful on the sabbath?” in a grain field (2:24).

After Jesus had returned from a trip across the Sea of Galilee to “the other side”, a group of Pharisees ask him, “Why do your disciples not live according to the tradition of the elders, but eat with defiled hands?” (7:5 ). In Dalmanutha, some Pharisees approached Jesus “and began to argue with him, asking him for a sign from heaven, to test him” (8:11). And then, in the passage before us this week, once Jesus is in Judea some Pharisees come “to test him” by asking this question, “Is it lawful for a man to divorce his wife?” (10:2).

Jesus, of course—being well-schooled in the business of public disputation on matters of Torah—responds to their question with his own question: “What did Moses command you?” (10:3). This, of course, steers the discussion into the heart of the matter: the specific text from Torah which provided guidance on this matter. From here, the debate continues along a familiar pathway, with the Pharisees offering a scripture passage (10:4, referring to Deut 24:1), Jesus responding with an interpretation (10:5) followed by his proposing one scripture passage of relevance (10:6, quoting Gen 1:27) followed immediately by another passage (10:7–9, quoting Gen 2:24). The to-and-fro of scripture citation, interpretation, counter-proposal, and argumentation, is familiar ground for Jesus.

On the matter of divorce, there were different schools of thought amongst Jewish teachers. In biblical law, a husband has the right to divorce his wife, but a wife cannot initiate a divorce (Deut 24:1). A husband could initiate a divorce if he believes there is some uncleanness in his wife. Understandings as to what such uncleanness might varied. At one extreme was the narrow interpretation that divorce was possible only because of adultery. According to the Mishnah (Gittin 9.10), this view was articulated by Beit Shammai, those following the interpretation set forth by rabbi Shammai.

A much broader understanding was adopted within Beit Hillel, that almost any dissatisfaction with his wife’s behaviour could validate a man’s application for a divorce. The Mishnah tractate reports “he may divorce her … because she burned or over-salted his dish … even if he found another woman who is better looking than her and wishes to marry her” (Mishnah, Gittin 9.10).

The line that Jesus takes is to reject the wider understanding; he tells the Pharisees this was decreed by Moses “because of your hardness of heart” (Mark 10:5). That seems to indicate something contingent about the nature of this particular commandment. So Jesus here is practising the kind of evaluation of texts that we know various Torah interpreters practised. He does not simply quote the text and then say “that’s it, case closed”; he undertakes an evaluative interpretation of those older words.

This is a very rabbinic way to operate. A later rabbinic text, Makkot 23b—24a in the Babylonian Talmud (probably compiled in the 6th century CE) reports a debate between rabbis as to how many commandments were included in the Torah. Rebbi Simlai ventured a count of 613 (“two hundred and sixty five prohibtions in accordance with the days of the sun; and two hundred and forty eight positive commandments in accordance with the limbs of a person”). Rav Hamnunya then suggested that David had identified eleven commandments (citing Psalm 15), then Isaiah narrowed this to six (Isa 33:15), then Micah spoke the three key commandments (“do justly, and love mercy, and walk discreetly with your God”, Mic 6:8).

Next, Isaiah is cited once more, from the beginning of what we identify as Third Isaiah (“guard justice and do righteousness”, Isa 56:1). Finally, Amos is cited, with the singular command, “seek me and live” (Amos 5:4). To which Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak responded, saying “maybe it means to seek out the entire Torah?”—although he then proceeds to cite Hab 2:4, “the righteous shall live by his faith”, as the foundational commandment. (We know this obscure prophetic text because it forms the basis for Paul’s declaration of the Gospel to the saints in Rome at Rom 1:16–17).

You can read the whole debate (in Aramaic, with English translation) on the website Sefaria:

https://www.sefaria.org/Makkot.24a.27?ven=Sefaria_Community_Translation&lang=bi

All of which is to say that, as we read and hear the passage from Mark 10 that is offered by the lectionary, we need to understand the context and apply our learnings from that to the text. The words of Jesus should not be plucked out of context, made to stand in bare isolation, and treated as an eternal, unchanging word of the Lord. That is to misunderstand what is going on in this passage.

Jesus and the Pharisees are setting forth their different understandings. Through this process of debate and discussion, deeper understanding emerges. Rabbis even to this day value vigorous debate and robust questioning, for this is the way that God’s truth emerges. I learnt this with a vengeance some decades ago, when ministering in a congregation set in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney, where there was a high concentration of Jewish residents.

Many of the Jewish residents came to the weekly School for Seniors that we ran in the church building, and quite a few Jews joined with Christians in the weekly Jewish—Christian Dialogue group that I ran. We had many Fridays of vigorous disputation and robust argumentation—all in a good cause, all as friends together. And the same congenial experience was repeated many times during my years on the National Uniting Church Dialogue with the Jewish Community!

So let us not read the declaration of Jesus about divorce as a set-in-stone decree, valid for all times. As a divorced and remarried person, I know all too well the dangers that are inherent in such a reading. For a time, some decades after my divorce, I was pursued online by a rabid fundamentalist who condemned me as “doomed to hell”, told me that I was an “apostate” who “has been deceived”, that I am “hell bound without repentance”, and offering the graphic description of my fate, that I was condemned to the eternal lake of burning sulphur (Rev 20:7–10 and 21:8). All because I was divorced and remarried!!!

Society changes, situations develop, understandings deepen and are reshaped by our contexts. We rightly, today, accept that divorce may be the best way ahead for some people, on pastoral and personal grounds. Our laws accept that, and my denomination, the Uniting Church in Australia, accepts that. We bring more factors into the discussion that were not being considered in the brief interaction that Mark reports in ch.10.

In like fashion, countless people have been hurt—many of them deeply hurt—by the fundamentalist insistence that, when he debated the Pharisees in this encounter, Jesus was setting forth “a biblical definition of marriage” that is immutable, when he said, “from the beginning of creation, ‘God made them male and female.’ ‘For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh.’” (Mark 10:6–7).

Such people place the words of Jesus over and against those people who identify as “queer”—gay, lesbian, bisexual, and also now transgender—and whose love, deep and abiding, for a person of the same gender as they are. Forbidden by law to marry until recent years (2017 in Australia), these people are told “marriage is between a man and a woman”, citing the words of Jesus from this week’s Gospel passage. Again, the argument is simplistic: “Jesus said this, this is what it means, end of discussion, case closed”. It’s a hurtful and uninformed way to operate, in my opinion.

What would Jesus have done if confronted with scenarios of increased domestic violence and toxic masculinity feeding unhealthy and damaging relationships? Would he have replied as a fundamentalist: “that’s what Moses said, that’s it”? Or would he have offered a rabbinic explanation, offering different factors and exploring new pathways of understanding? I suspect the latter.

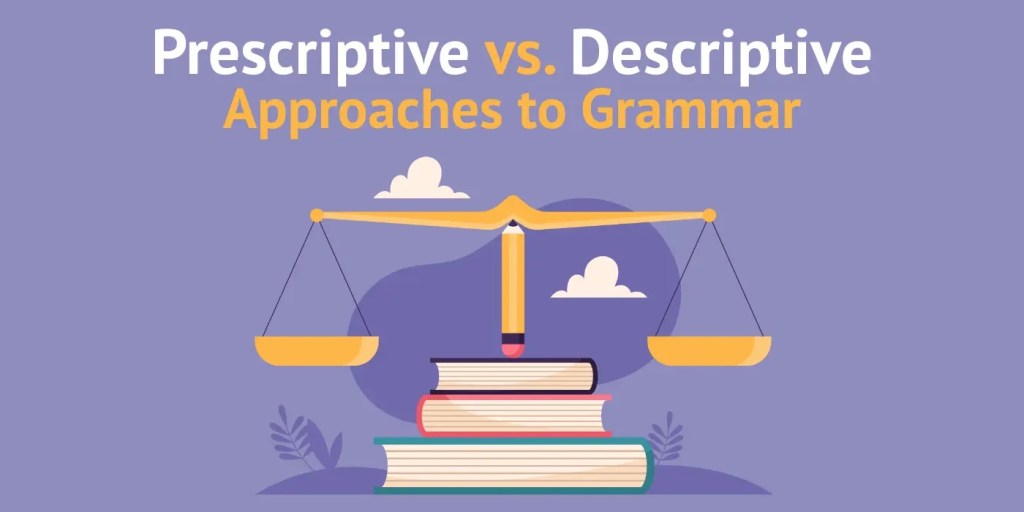

So let’s not use this passage as a word that is prescriptive—that says something like “this is what the text says, and it expresses exactly how God defines marriage and forbids divorce, and that stands for all times and all places”. The text, in my opinion, gives no indication that a general principle, prescribing human behaviour, is being set forth. Indeed, the Genesis passage about marriage that is cited by Jesus is not from a book that sets out Torah commandments; rather, it is from a narrative work.

Rather, I see it as descriptive—that offers a description of how human beings behave and what should guide us as we navigate our way through life, based on our experiences and reflection on how things have been for us. Indeed, whilst the quote from Moses (in Deut 24) does have a legal tone to it, it needs to be understood within the back-and-forth that characterised rabbinic interpretation of Torah (an ethos shared by Jesus); and the Genesis quote, it should be noted, comes from a book that contains aetiological narratives (which I have explained in my earlier blogs on the Genesis narratives), describing the world and the place of humans in that world on the basis of observation and experience.

So let’s offer Jesus—and the Pharisees—the respect that they deserve as they discuss and debate, and not try to press their words in a direction that they never intended.

For more on this passage, see

For more on the matter of same-gender marriage, which has been permissible within my church since 2018, see