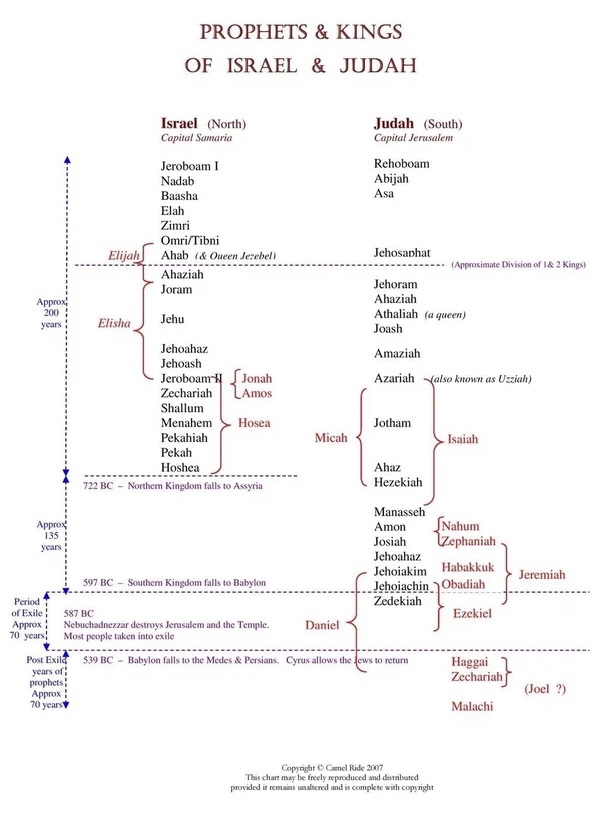

As we follow the various readings from the Prophets during this season after Pentecost in Year C, we encounter a striking passage this coming Sunday. It contains an impassioned love poem, in the words of God, concerning the people of Israel (Hosea 11:1–11).

The poem depicts God as a human being, loving Israel as a child (11:1), calling to them (11:1–2), taking them up into God’s arms (11:3), kissing them and feeding them (11:4, showing warm and tender compassion (11:8), withholding anger (11:9), welcoming them back as they return from their wandering (11:11). God is the patient, loving, caring parent.

This is a striking passage. It confronts us in two ways: first, by depicting God in human form, and second, as it is a passage in the Old Testament which depicts God in a way that is quite different from many other passages that are often cited, where God’s anger with Israel bubbles over into aggressive punishment. I can’t count the number of times that I have heard this aspect of God used to characterise (or, indeed, caricature) the God of the Old Testament as violent and vengeful.

First, let’s consider the depiction of God in ways that indicate the deity is acting like a human being. Even thought there are clear injunctions against having any images (or idols) representing God (Exod 20:4, 23; Lev 19:4; 26:1; Num 33:50–52; Deut 5:8; 27:15; Isa 42:17), God is nevertheless portrayed in the scriptures as being human-like.

In Deuteronomy, Moses had reminded the the Israelites of what had taken place on Mount Horeb (Sinai of Exodus 19): “the Lord spoke to you out of the fire; you heard the sound of words but saw no form; there was only a voice” (Deut 4:12). He continued, “since you saw no form when the Lord spoke to you at Horeb out of the fire, take care and watch yourselves closely, so that you do not act corruptly by making an idol for yourselves, in the form of any figure—the likeness of male or female, the likeness of any animal that is on the earth, the likeness of any winged bird that flies in the air, the likeness of anything that creeps on the ground, the likeness of any fish that is in the water under the earth” (Deut 4:15–18). That’s a comprehensive list of what is prohibited!

Nevertheless, at many places in Hebrew Scripture, God has eyes and ears (2 Chron 6:40; 7:15; Ps 34:15; Dan 9:18), a mouth (Deut 8:3; 2 Chron 36:12; Isa 1:20; 34:16; 40:5; 58:14; 62:2; Jer 9:12; 23:16; Mic 4:4) and nostrils (Deut 15:8; 2 Sam 22:9, 16; Ps 18:8, 15; Isa 65:5), as well as hands (Exod 9:3; 16:3; Josh 4:24; Job 12:9; Ps 75:8; Isa 5:25; Ezek 3:22) and feet (Gen 3:8; Ps 2:11–12; 18:9; Isa 63:3; Ezek 43:7; Nah 1:3; Zech 14:3–4).

God speaks (Gen 1:3; Exod 33:11; Num 22:8; Ps 50:1; Ezek 10:5; Jer 10:1; listens (Exod 16:12; Ps 4:3; 34:17; 69:33; Prov 15:29), and smells the aroma of sacrifices as smoke rises to the heavens (Gen 8:21; Lev 1:13, 17; 2:2, 9; 3:5, 11, 16; 4:10, 31; 6:15; 8:21; 17:6; cf. Lev 26:31). God even whistles (Isa 7:18) and shaves (Isa 7:20)!

This depiction of God in human form is despite the polemic of Psalm 115, which derides idols as “the work of human hands. They have mouths, but do not speak; eyes, but do not see. They have ears, but do not hear; noses, but do not smell. They have hands, but do not feel; feet, but do not walk; they make no sound in their throats.” (Ps 115:4–7; see also Deut 4:28; Isa 44:18; Hab 2:18).

The God with eyes and ears, then, laughs (Ps 2:4), has regrets (Jer 42:10), feels grief (Ps 78:40) and joy (Isa 62:5; Jer 32:41; Zeph 3:17). God experiences jealousy (Exod 20:5; Deut 4:24; 5:9; 6:15; 32:19–21; Josh 24:19; Job 36:33)—jealousy so intense that his wrath “burns like fire” (Ps. 79:5). “Who can stand before his indignation? Who can endure the heat of his anger? His wrath is poured out like fire, and by him the rocks are broken in pieces”, says Nahum (Nah 1:2).

Which brings us to the stereotype I noted above: that the God of the Old Testament was always violent and vengeful. To be sure, we can see intense flashes of God’s anger in incidents told in the historical narratives (Num 25:1–9; Deut 28:15–68; 29:19–28; Judg 2:11-23; 2 Sam 6:1–11) and in the regular refrain, “the anger of the Lord was kindled against XX” (Exod 4:14; Num 11:33; 12:9; 32:13; Deut 6:15; 7:4; 11:17; 29:27; Josh 23:16; Judg 2:14, 20; 3:8; 10:7; 2 Sam 6:7; 24:1; 1 Ki 16:7, 13, 26, 33; 22:53; 2 Ki 13:3; 17:17; 21:6; 23:19, 26; 1 Chron 13:10; 2 Chron 21:16; 28:25; 33:6; Ps 106:40).

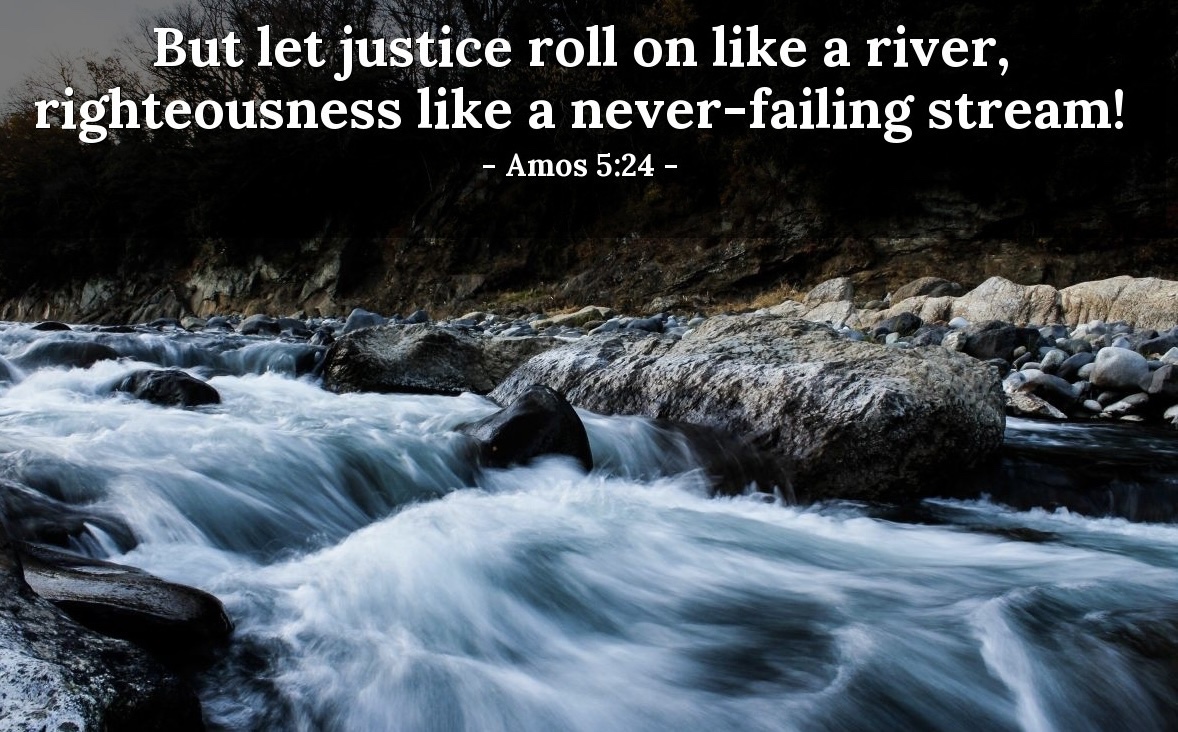

The prophets proclaim that judgement will fall with a vengeance on the people on the Day of the Lord (Isa 2:12–22, 13:6–16; Jer 46:10; Joel 2:1–11; Amos 5:18–24; Zeph 1:7–18; Mal 4:1–5) whilst the psalmists invoke the wrath of the Lord upon their enemies (Ps 2:5, 12; 21:9; 56:7; 59:13; 110:5–6), note that God’s wrath punishes Israel (Ps 78:49, 59, 62; 88:7, 16; 89:38; 90:7–11), and petition God to turn his wrath away from them (Ps 6:1; 38:1; 79:5; 89:46). Such punishment is the consequence of breaking the covenant (Lev 26:14–33; 2 Sam 7:14; Ps 89:31–32; Jer 5:7–9; Ezek 7:1–4).

******

However, this is not the sum total of God’s character in Hebrew Scriptures; there is much more to be said about God. The prophets, for instance, not only proclaim the coming “day of the Lord”, but also look with hope to a time when peace will reign and justice will be done (Isa 2:1–4, 5:1–7, 9:6–7, 28:16–17, 42:1–9, 52:9–10, 66:12; Ezek 34:25; Mic 4:1–7; Hag 2:9; Zech 8:12).

The psalmists praise God for the steadfast love (heșed) that he expresses to Israel (Ps 5:7; 6:4; 13:5; 17:7; 18:50; 21:7; 25:6–10; 26:3; 31:7, 16, 21; 33:5, 18, 22; 36:5–10; 40:11; 42:8; 44:26; 48:9; 51:1; 52:8; 57:3, 10; and so on) and prophets recognise this same quality in God (Isa 54:10; 55:3; 63:7; Jer 9:24; 16:5; 32:18; 33:11; Dan 9:4). As Jeremiah sings, “the steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness” (Lam 3:22).

Micah asks, “who is a God like you, pardoning iniquity and passing over the transgression of the remnant of your possession?” (Mic 7:18). The answer to that question is sounded again and again in the refrain, “the Lord is a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin” (Exod 34:6; Num 14:18; Neh 9:17; Ps 86:5, 15; 103:8; 145:8; Joel 2:13; Jon 4:2).

This steadfast love (heșed)—also translated as loving kindness, or as covenant love—is a consistent characteristic of the God found in the pages of the Old Testament, along with the God who executes judgement and inflicts punishment. Like human beings, the God of Hebrew Scripture is complex, with multiple characteristics, exhibiting a wide range of behaviours.

Hosea 11 not the only passage where the deity is depicted as acting a human being. God is occasionally imaged as a woman, such as in the palmist’s comparison, “as the eyes of servants look to the hand of their master, as the eyes of a maid to the hand of her mistress, so our eyes look to the Lord our God, until [God] has mercy upon us” (Ps 132:2–3).

God is described as being “like a woman in labour; I will gasp and pant” (Isa 49:15); she gives birth (Deut 32:18) and comforts her child “as a mother comforts her child” (Isa 66:13). The psalmist compares themself to “a weaned child with its mother; my soul is like the weaned child that is with me” (Ps 131:2). Such female descriptors for God emerge in the New Testament as Jesus evokes the image of “a hen [who] gathers her brood under her wings” (Matt 23:37; Luke 13:34), as well as in the parable of the woman searching for her lost coin (Luke 15:8–10).

In the love song of Hosea 11, God exudes heșed, loving kindness, or covenant love. In return, God expects that Israel will demonstrate that same covenant love (Hos 4:1), for “I desire steadfast love and not sacrifice” (Hos 6:6). The prophet calls to the people, “return to your God, hold fast to covenant love (heșed) and justice (mishpat), and wait continually for your God” (Hos 12:6).

The chapter offers beautiful insights into how God deals with people; it stands in stark juxtaposition to the many passages that describe the anger of the deity. It reminds us that the mercy of God, expressed in deep covenant love, must always be held alongside the justice of God, expressed in angry punishments meted out when that covenant is broken. Indeed, Hosea describes the covenant relationship between Israel in this manner: “I will take you for my wife in righteousness and in justice, in steadfast love, and in mercy” (Hos 2:19).

Mercy and justice are two sides of same coin, two key aspects of the character of God. Accordingly, God requires of us both mercy and justice, as Jesus notes: “the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faith” (Matt 23:23).

*****

See also