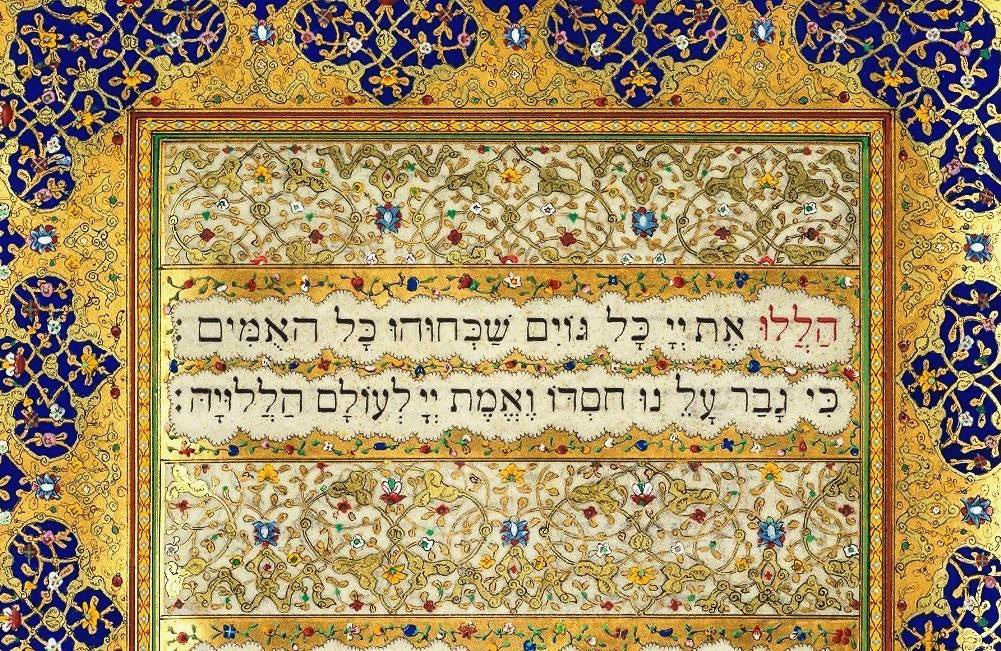

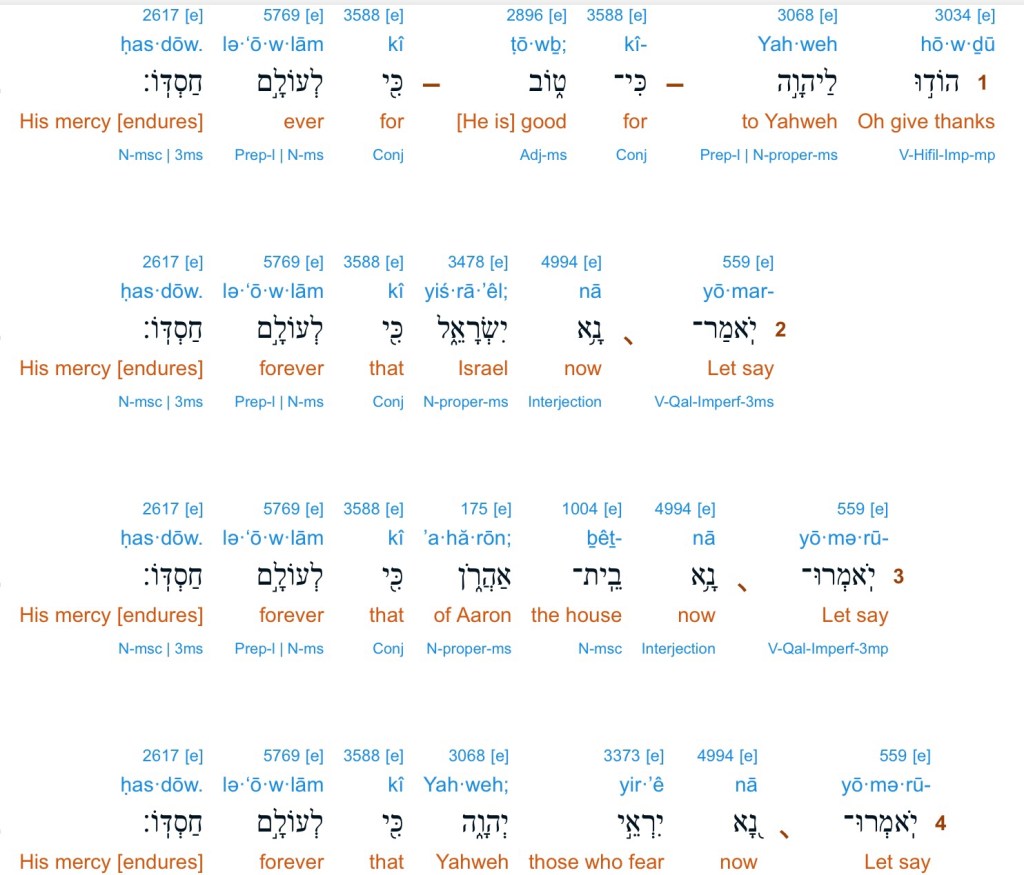

I set myself a challenge: develop a fully-rounded theology from just one psalm. Easy, I thought; the shortest psalm, 117, has a number of key elements in its two verses: praise (“praise the Lord” twice, at the beginning and the end), adoration (“extol him”), a recognition of divine love (“great is his steadfast love towards us”), the universal orientation of that love (“all peoples”), and the assurance of divine fidelity (“the faithfulness of the Lord endures forever”).

There: done and dusted! … although, I think, on further reflection, that this looks more like the outline of a litany (praise—adoration—intercession —blessing) than a fully-developed theology. As a litany, it is succinct; as a theology, it is still quite deficient.

So, what about a challenge to develop a fully-rounded theology, not from the shortest psalm, but from the longest psalm? For just two psalms later, we have the 176–verse grand acrostic of the Hebrew Scriptures: Psalm 119—a small portion of which (119:105–112) is offered by the lectionary this coming Sunday. What would a theology look like, using only the verses in this psalm? And how full (or inadequate) would that theology be?

I love the way that this wonderfully artistic creation contains key elements of a theological understanding of the world. There are components regarding the nature of God, the human condition, and the divine response to that human condition. There is much to be gleaned regarding revelation and also salvation. And there are indications that touch on the character of living a faithful life, as well as signs of what the future is to be. All of these elements contribute to a fully-developed theology, surely?

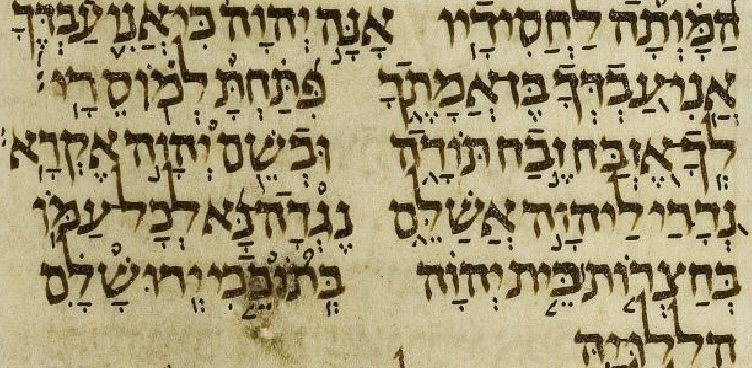

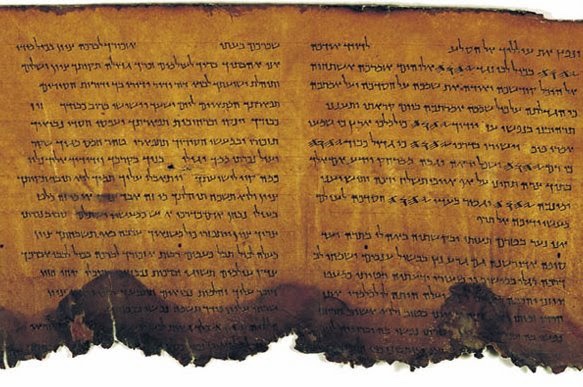

This longest psalm of all, Psalm 119, is an acrostic series of 22 eight-verse stanzas (arranged alphabetically) in which the author(s) consistently affirm the value and importance of the teaching (Hebrew, torah) which sits at the centre of faith for the person singing this psalm. “I will delight in your statutes; I will not forget your word” (Ps 119:16). By contrast to “the arrogant”, whose “hearts are fat and gross”, the psalmist declares, “I delight in your law” (Ps 119:70).

The psalm includes the petition, “let your mercy come to me, that I may live, for your law is my delight” (Ps 119:77), noting that “if your law had not been my delight, I would have perished in my misery” (Ps 119:92). It also affirms, “I long for your salvation, O Lord, and your teaching (torah) is my delight” (Ps 119:74). Echoing these words many centuries later, Paul, in the midst of his agonising about Torah in Romans 7, is able to affirm, “I delight in the law of God in my inmost self” (Rom 7:22). Delight for the Law runs through Jewish history.

This longest of all psalms is a series of 22 meditations on teachings, or Torah, which is usually translated as “law”. It contains regular affirmations of the place of Torah in personal and communal piety: “give me understanding, that I may keep your law and observe it with my whole heart” (v.34); “Oh, how I love your law! it is my meditation all day long” (v.97).

The psalmist contrasts their devotion to Torah with those who neglect or ignore it: “I hate the double-minded, but I love your law” (v.113); “I hate and abhor falsehood, but I love your law” (v.163). They rejoice that “great peace have those who love your law; nothing can make them stumble” (v.165). From this long and persistent affirmation of Torah throughout all 22 stanzas, we can indeed devise a fully-fledged theology, canvassing many of the key issues that we have come to associate with theology.

(In what follows, I will refer to the psalmist as “they”, making no assumptions about who they were, even their gender. As psalms were collective songs, it is reasonable to suggest that they were developed within the community, by members of the community—so “ they” is a reasonable assumption, I feel.)

1 God

Undergirding the joyful appreciation of Torah in the lengthy psalm is a consistent trust in God, who is consistently acknowledged as the author and giver of Torah, but is also celebrated as creator: “your hands have made and fashioned me” (v.73). That affirmation reflects famous words sung in another psalm, “I praise you [God], for I am fearfully and wonderfully made; wonderful are your works; that I know very well” (Ps 139:14).

God’s creative power is at the centre of Hebrew Scripture. It is celebrated in passing in many psalms (Ps 8:3–8; 33:6–7; 74:16–17; 95:4–5; 96:5; 100:3; 103:14; 115:15; 121:2; 124:8; 136:4–9; 146:5–6); in the majestic celebratory psalm, Psalm 104, which rejoices, “Lord, how manifold are your works! In wisdom you have made them all” (Ps 104:24); and in the carefully-crafted priestly account of creation that stands at the head of Hebrew Scripture (Gen 1:1–2:4a). It is noted with appreciation also in psalm 119 (v.73).

A second element in this psalm is that God’s mercy is valued; “great is your mercy, O Lord” (v.156), and so the psalmist prays, “let your mercy come to me, that I may live; for your law is my delight” (v.77). This is a common refrain in other psalms, where God is asked to show mercy (Ps 25:6; 40:11; 51:1; 123:2, 3). As one proverb says, “no one who conceals transgressions will prosper, but one who confesses and forsakes them will obtain mercy” (Prov 28:13). A similar sentiment is offered by Isaiah: “the Lord waits to be gracious to you; therefore he will rise up to show mercy to you, for the Lord is a God of justice; blessed are all those who wait for him” (Isa 30:18).

Then, we might note the love of God. A recurrent refrain in Hebrew Scripture is a celebration of “the steadfast love of the Lord” (Exod 34:6; 2 Chron 30:8–9; Neh 9:17, 32; Jonah 4:2; Joel 2:13; Ps 86:15; 103:8, 11; 111:4; 145:8–9). This affirmation presents God as “merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for the thousandth generation”.

God is praised for showing love by redeeming the people in the Exodus (Exod 15:13) and then guaranteeing abundance in the land is promised to the people: “he will love you, bless you, and multiply you; he will bless the fruit of your womb and the fruit of your ground, your grain and your wine and your oil, the increase of your cattle and the issue of your flock, in the land that he swore to your ancestors to give you”, says Moses (Deut 7:13).

Solomon later praises God, saying “you have shown great and steadfast love to your servant my father David … and you have kept for him this great and steadfast love, and have given him a son to sit on his throne today” (1 Ki 3:6; also 2 Chron 1:8), and then as he dedicates the Temple, he prays “there is no God like you in heaven above or on earth beneath, keeping covenant and steadfast love for your servants who walk before you with all their heart” (1 Ki 8:23; 2 Chron 6:14).

When the foundations of the Temple are laid, after it has been destroyed by the Babylonians, the people sing, “praising and giving thanks to the Lord, ‘for he is good, for his steadfast love endures forever toward Israel” (Ezra 3:11). When a covenant renewal ceremony takes place under Nehemiah, he addresses God as “a gracious and merciful God” and continues, “the great and mighty and awesome God, keeping covenant and steadfast love” (Neh 9:31–32). A number of prophets refer to God’s enduring, steadfast love (Isa 16:5; 43:4; 54:8, 10; 63:7; Jer 9:24; 31:3; 33:11; Dan 9:4; Hos 2:19; 11:3–4; Jonah 4:2; Micah 7:18–19; Zeph 3:17).

Reference is made to the steadfast love of God on seven occasions in this psalm (verses 41, 64, 76, 88, 124, 149, and 159). Such love is often linked with Torah—“the earth, O Lord, is full of your steadfast love; teach me your statutes” (v.64); and again, “deal with your servant according to your steadfast love, and teach me your statutes” (v.124). An important function of Torah is thus to communicate the extent of divine live.

In tandem with God’s mercy and steadfast love, so divine justice is also noted. “Great is your mercy, O Lord; give me life according to your justice” (v.156); and “in your steadfast love hear my voice; O Lord, in your justice preserve my life” (v.149).

Justice, of course, is at the heart of the covenant that God made with Israel. Moses is said to have instructed, “justice, and only justice, you shall pursue” (Deut 16:20), the king is charged with exhibiting justice (Ps 72:1–2; Isa 32:1), whilst many prophets advocate for justice (Isa 1:17; 5:7; 30:18; 42:1–4; 51:4; 56:1; Jer 9:24; 22:3; 23:5; 33:15; Ezek 18:5–9; 34:16; Dan 4:37; Hos 12:6; Amos 5:15, 24; Mic 3:1–8; 6:8).

So God, says the psalmist, holds the people of the covenant to the standard set in Torah: “you rebuke the insolent, accursed ones, who wander from your commandments” (Ps 119:21). The assumption throughout this psalm is that the creator God is personal, approachable, relatable; just and fair, kind and loving.

See further posts at