A sermon preached at Dungog Uniting Church on Easter Sunday 2025.

Today is a day of celebration. We gather, we sing, we exclaim “Christ is risen!” Joy fills the air; expectation and hope are abundant. It’s a fine way to emerge from the sombre mood of Friday, when we last gathered, on day of mourning, to remember the sombre reality, “Christ has died”.

On that day, we remembered again the story of the last days of Jesus: a story of betrayal and denial, of physical abuse and verbal mocking, of abandonment and death, of grief and despair.

And yet, today, we have moved from that deep despair, into abundant joy.

Today is a day of celebration.

Today is also a day of mystery. It is a day that we cannot fully explain with simple phrases and formulaic responses. It is a day that invites us to pause, reflect, and ponder.

Last week, Lurline quoted what she called “the most electric sentence of the Bible”: “he is not here; he has risen!”

We have heard that electric expression of joy in the reading from Luke’s Gospel. “Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here, but has risen.” (Luke 16:5)

And so we greet one another on this day: Christ is risen! Christ is risen indeed!!

That electric sentence provokes many questions.

What is it that actually happened?

How was the stone moved?

Where is the body of Jesus?

How exactly was Jesus raised from the dead?

What is the form that Jesus now takes?

What does it mean for us to hold the hope that we, too, will be raised from our death?

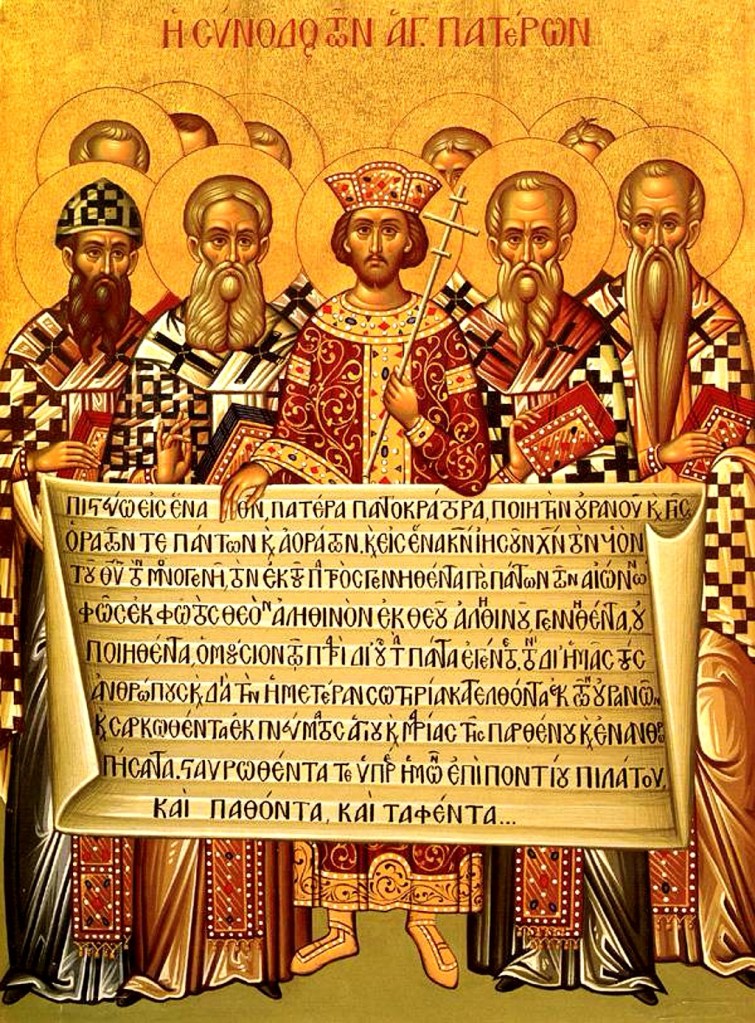

This day of mystery confronts us with a host of questions. Preachers and priests, scholars and writers, over decades and centuries, have asked these questions, have explored them in their words, have sought to provide explanations, all the while intending to buttress and strengthen our faith on this day of mystery.

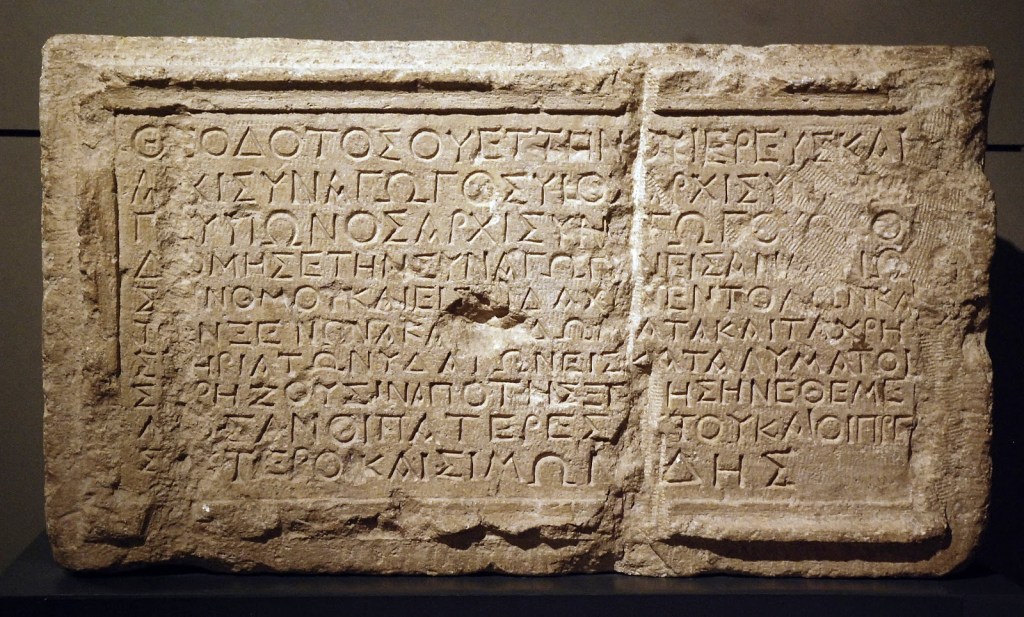

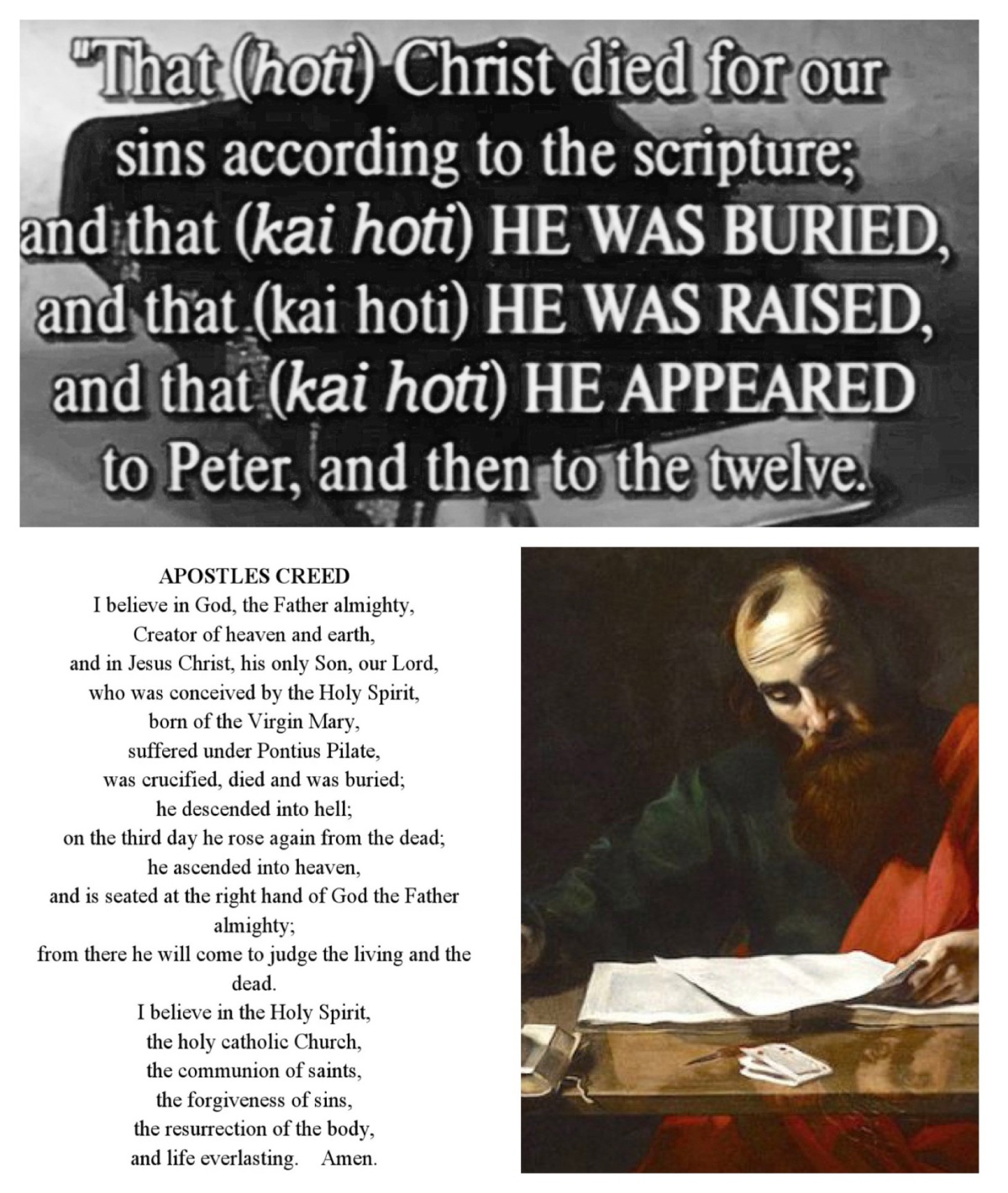

Did the resurrection really happen? is one of the questions that is often asked on or around this day. What was the historical reality of the day? I have to say, that is a very modern question. It may surprise you, but for centuries, this was not a question that troubled the minds of believers. It is really only something that has concerned us in the last few centuries—from the time of The Enlightenment, when the focus shifted from lives lived by faith to lives exploring scientific and historical realities.

The question about “what really happened?” is a classic post-Enlightenment question. It’s not something that occurred to those of ancient times. So the biblical texts of antiquity don’t provide any explanation that satisfies us modern listeners and readers.

Indeed, this is a question that cannot be answered by a simple historical “proof”. The resurrection is, by its nature, something that transcends the material, earthly focus of our modern era. It resists clearcut scientific or historical questions. It remains, in the end, a mystery.

What actually happened to the body of Jesus? is another question that is often asked about today—which also reflects the time in which we live, when “what happened?” is often an important question. And the answer offered by numerous writers has varied, ranging from “the body was stolen” through to “a miracle happened”. Again, a satisfactory explanation is beyond us. It is a mystery.

How was the stone removed from the doorway to the tomb? is another question that is asked. Mark’s Gospel says that when the women came to the tomb to anoint Jesus, “they saw that the stone, which was very large, had already been rolled back” (Mark 16:4). So, too, does Luke (Luke 16:2); neither evangelist was interested in providing any explanation about this curious feature.

The account in Matthew’s gospel, however, does venture an answer: when the women arrive at the, “suddenly there was a great earthquake; for an angel of the Lord, descending from heaven, came and rolled back the stone and sat on it” (Matt 28:2). That’s the explanation, it seems. This evangelist then continues, “his appearance was like lightning, and his clothing white as snow; for fear of him the guards shook and became like dead men” (Matt 28:3–4). Understandably!

However, we need to note that Matthew’s account had also reported an earthquake at the very moment that Jesus had died on the cross: “Jesus cried again with a loud voice and breathed his last. At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom. The earth shook, and the rocks were split. The tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised. After his resurrection they came out of the tombs and entered the holy city and appeared to many.” (Matt 27:50–53).

That’s quite a story! and even more striking, perhaps, is the fact that none of the other evangelists report this incredible series of events: an earthquake and the raising of dead people at the moment Jesus died. It’s not in Mark’s earliest version; and it’s not in Luke’s later account, that we heard this morning. We can see, I hope, that this is part of the particular way that Matthew—a faithful Jew who held to the hope that God would act to come to earth to bring in the kingdom of God—tells the story of Jesus.

The earthquake that happens as Jesus dies and the second earthquake that comes just as the women discover the empty tomb both draw on apocalyptic imagery that the later prophets used and developed in their prophetic oracles. It’s not an actual historical account. It’s a vivid, dramatic telling of the story, designed to highlight this one central fact: God acted, God came to us, God raised Jesus from the dead, the kingdom of God is now present!

So today is a day of celebration; we celebrate that God has determined to be amongst us in a new, startling, and dramatic way. That is what motivated the women, when the discovered the tomb to be empty, made haste to return to the other disciples, to tell them “he is not here; he has risen” (Luke 24:8).

This is also a day of mystery, for the way that God came to us, raising Jesus from the dead, poses a range of questions, as I have considered. There is much to celebrate, and yet so many questions to consider. And that is probably why the apostles—Peter and Andrew, James and John, Matthew and Bartholomew and Thaddeus and Thomas—all men, it must be noted, heard what the women told them, and as Luke crisply reports: “it seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them” (Luke 24:11). Ah, the patriarchy!

It was, they presumed, a strange story, told by hysterical women, completely unbelievable—even though the men in the tomb had explicitly reminded the women of what Jesus had said “while he was still in Galilee, that the Son of Man must be handed over to sinners, and be crucified, and on the third day rise again” (Luke 24:7).

It’s a day of celebration; a day of mystery; and perhaps, in the end, today is a day that calls for faith. At the heart of the story of Jesus, as we have heard over the last few days, is a story of betrayal and denial, of physical abuse and verbal mocking, of abandonment and death, of grief and despair. It could very well lead us to a pessimistic view of the world, and to dampen our hopes.

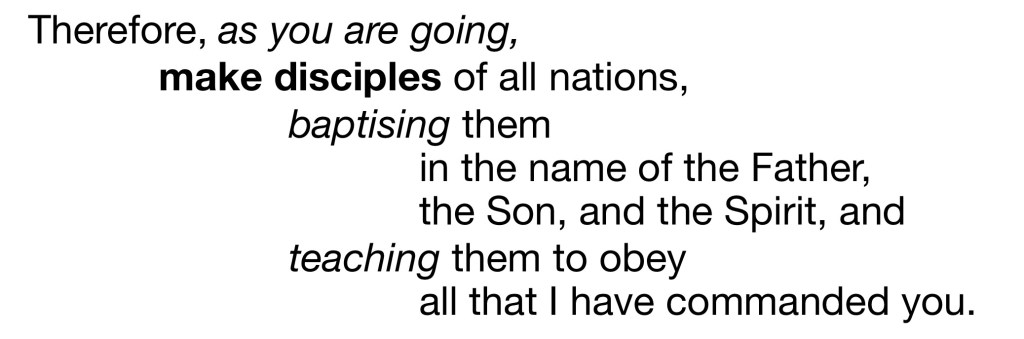

Yet today is a day that calls us to have faith. To have faith that death is not the end of life. To have faith that there is more to our existence than our physical bodies. To have faith that God’s desire and intention is to work through even the despair of the lowest moments and to offer us the hope of what we can but glimpse today.

For that is what the resurrection of Jesus stands for. We may not be able to answer the many questions that it poses. But we can affirm, with the faithful people of ages past, and across the world M.today, and those still to come in the future beyond us, that “Christ has died. Christ is risen“ … “Christ is risen indeed! Alleluia!” For God is with us.