In the passage which the Narrative Lectionary places before us this coming Sunday (from 1 Kings 19), we come to Elijah; one of the key prophetic figures whose deeds are recounted in the books of the Kings or whose words are collected within the Hebrew Scriptures under the catch-all second section of Nevi’im (Prophets).

Elijah, famous for being described as “a hairy man, with a leather belt around his waist” (2 Ki 1:8), was first introduced as Elijah the Tishbite, meaning he came from Tishbe in Gilead (1 Ki 17:1), a place whose precise location has occasioned some debate. See

This initial portrayal of Elijah is nested within the accounts of that long period of time when Israel was ruled by kings, when prophets functioned as the conscience of the king and the voice of integrity within society. The distinctive dress of Elijah perhaps sets him apart from the court of the kings, where a more “civilized” dress code was presumably operative. Nevertheless, Elijah does have some engagement with the kings who ruled at the time he was active: Ahab, and then Ahaziah. Indeed, his distinctive dress points to his emboldened attitude towards those kings.

Elijah operated during the period when Ahab ruled Israel; he figures in various incidents throughout the remainder of 1 Kings—most famously, in the conflict with the prophets of Baal which came to a showdown on Mount Carmel (1 Ki 18), and then later in his confrontation with Ahab and his wife Jezebel, over the matter of Naboth’s vineyard (1 Ki 21). Like Jesus, Elijah was no shrinking violet!

Elijah first appears in the narrative of the various kings, seemingly out of nowhere, just after King Ahab had taken as his wife Jezebel, daughter of King Ethbaal of the Sidonians, who presumably influenced him to begin his worship of Baal (1 Ki 17:31–33). In the same way, at the end of his time of prophetic activity, Elijah simply disappears from sight soon after Kong Ahaziah died. Elijah hands over his role to his successor, Elisha, and as “a chariot of fire and horses of fire separated the two of them”, Elijah ascends in a whirlwind into heaven (2 Ki 2:1–15).

In the book we know as 1 Kings, the compiler of the Deuteronomic History (which stretches from Deuteronomy through Joshua and Judges to Samuel and then Kings) reports many incidents which attest to the courage and power of Elijah. The boldness of Elijah is evident in the confrontations that he has with various rulers; this is made clear, centuries later, to the followers of Jesus, in the earliest account of his life, when John the baptiser is depicted as a fiery desert preacher, calling for repentance, just as Elijah had called the kings to account (Mark 1:1–8).

In a later account of Jesus, there is a clear inference connecting John with Elijah when Jesus notes, “Elijah is indeed coming and will restore all things; but I tell you that Elijah has already come, and they did not recognize him, but they did to him whatever they pleased” (Matt 17:11–12).

Then, in his sermon in Nazareth (Luke 4:16–30), Jesus refers to the first reported miracle of Elijah, when he provided a widow in Zarephath with food and oil that “did not fail”, even though the land was in drought (1 Ki 17:1–16). In subsequent incidents in 1 Kings, Elijah raises a dead son (17:17–24), directly confronts King Ahab with his sins (18:1–18), and famously stares down the prophets of Baal in a mountaintop showdown (18:19–40), leading to the breaking of the drought (18:41–46).

Elijah later condemns Ahab over his unjust seizure of the vineyard of Naboth (21:17–29) and then stands before Ahab’s son, King Ahaziah, to condemn him to death (2 Ki 1:2–16); a death “according to the words of of the Lord that Elijah had spoken” which is promptly reported (2 Ki 1:17).

During the rule of Ahab, Elijah had also most famously heard the Lord God “not in the wind … not in the earthquake … not in the fire”—but rather in something else, which the NRSV renders as “the sound of sheer silence” (1 Ki 19:11–12). This incident is, as noted, the story set before us by the lectionary this coming Sunday. We need to ponder what is being conveyed through the symbols employed in this story.

The three means by which God is said not to have appeared to Elijah reflect the very same means through which Moses, and the people of Israel, did experience the manifestation of the Lord God in their midst. When the escaping Israelites arrived at the Sea of Reeds, according to one version of this archetypal story, “the Lord God drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night, and turned the sea into dry land; and the waters were divided” (Exod 14:21).

The people later celebrated the defeat of the Egyptians who were pursuing them: “you blew with your wind, the sea covered them; they sank like lead in the mighty waters” (Exod 15:10). The wind was a sign of God’s presence, and an agent of divine protection—indeed, it was the very same “wind from God” which “swept over the face of the waters” at the beginning of creation (Gen 1:2). But for Elijah, the Lord God was “not in the wind”.

Then, as they had travelled through the wilderness, the people were accompanied by a blazing fire, another sign of divine presence: “the Lord God went in front of them in a pillar of cloud by day, to lead them along the way, and in a pillar of fire by night, to give them light, so that they might travel by day and by night” (Exod 13:21). The fire signalled the divine presence.

Indeed, the very same flaming fire had been manifested to Moses when he was but a mere shepherd in Midian; “the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed” (Exod 3:2). What follows is the account of the call of Moses; God tells him “I will send you to Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt” (Exod 3:10). The fire had been the assurance to Moses that it was the Lord God who was present. But for Elijah, the Lord God was “not in the fire”.

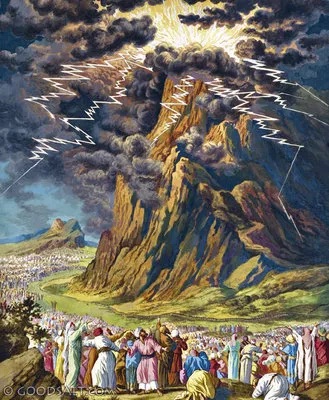

The same element of fire was present when Moses and the people ultimately arrived at Mount Sinai in the wilderness of Sinai (Exod 19:1–2). “Mount Sinai”, so the account goes, “was wrapped in smoke, because the Lord had descended upon it in fire; the smoke went up like the smoke of a kiln, while the whole mountain shook violently” (Exod 19:18). Associated with this there was “thunder and lightning, as well as a thick cloud on the mountain, and a blast of a trumpet so loud that all the people who were in the camp trembled” (Exod 19:16).

The scene at Sinai surely reflects the experience of an earthquake; the same phenomenon that prophets would later interpret as a sign of divine presence—indeed, divine judgement. “You will be visited by the Lord of hosts”, Isaiah subsequently tells the people of his time, “with thunder and earthquake and great noise, with whirlwind and tempest, and the flame of a devouring fire” (Isa 29:6).

Still later, Zechariah describes how “the Mount of Olives shall be split in two from east to west by a very wide valley”, and instructs the people, “you shall flee as you fled from the earthquake in the days of King Uzziah of Judah; then the Lord my God will come, and all the holy ones with him” (Zech 14:4–5).

Nahum reflects on the jealous and avenging nature of God, declaring that “his way is in whirlwind and storm, and the clouds are the dust of his feet; he rebukes the sea and makes it dry, and he dries up all the rivers; the mountains quake before him, and the hills melt; the earth heaves before him, the world and all who live in it” (Nah 1:2–5).

This dramatic motif continues on into later apocalyptic writings (Isa 64:1; 1 Esdras 4:36; 2 Esdras 16:12). The prophets and their apocalyptic heirs knew clearly that this whole dramatic constellation of events revolving around an earthquake was a sign of divine presence. But for Elijah, the Lord God was “not in the earthquake”. He was heard in something quite different.

What did Elijah hear? The Hebrew phrase in verse 12 is qol d’mamah daqqah. The King James Version translated this as “still small voice”. More recent translations have provided variants on how these words might be translated. Alternatives that are found include “the sound of a low whisper” (ESV), “a gentle whisper” (NIV, NLT), “a soft whisper” (CSB), or “the sound of a gentle blowing” (NASB). These reflect variations on the kind of nuance that the KJV was offering.

However, the NRSV option of translating this phrase as “the sound of sheer silence” is more confronting: the presence of God is sensed in the absence of sound; any communication from the deity comes, not in audible sounds, but in the utter absence of any sound. It is a striking paradox!

And in the context of the developing story of 1 Kings, the paradox is strong. Earlier, the prophet had stood firm against the might of Baal, the foreign god whom Ahab and Jezebel had prioritized in the life of Israel (1 Ki 18:17–40). When “the four hundred and fifty prophets of Baal and the four hundred prophets of Asherah who eat at Jezebel’s table” gathered on Mount Carmel, they failed to obtain any response from their god, the god of storms. No matter how intensely the pleaded, all they heard was “no voice, no answer, no response” (18:29).

Elijah, by contrast, prays to the Lord God and the fire of his god fell on the sacrificial altar; it consumed “the burnt offering, the wood, the stones, and the dust, and even licked up the water that was in the trench” (18:38). The victory was absolute and complete; the storm god had been defeated. And yet, the deity who accomplished this would communicate most personally and intimately with his chosen prophet, “not in the wind … not in the earthquake … not in the fire”, but rather in “a sound of sheer silence” (19:11–12). What a deliciously powerful irony!

Elijah was his own, distinctive man, with his own, distinctive encounter with God. He experienced God in a way quite different from what was experienced by Moses and the people of Israel. He experienced God in a way that stood apart from his contemporaries who were priests and prophets of Baal. For that reason, whilst the Lord God of Elijah stands over and against the Baal of Ahab and Jezebel, so too Elijah stands alongside and apart from Moses as a different, but equally great, leader of the people.