After a long stretch of passages taken from Paul’s long and complex letter to the Romans, the Revised Common Lectionary now leads us into shorter letters by Paul. First, we will spend four weeks considering passages from Philippians (Pentecost 17A to 20A), followed by five weeks focussed on the first letter to the Thessalonians (Pentecost 21A to 25A). After that, we have the Festival of the Reign of Christ, before we head into Advent, and there we stop the continuous pattern of the long season after Pentecost.

But before we leave Romans, it might be timely to look back, and consider the impact that this letter has had on Christianity. Romans is often seen as expressing the central paradox of the Gospel: God, being righteous, requires righteousness from people; God gives the Law to define that righteousness; yet in Jesus Christ, God has acted to make people righteous apart from this Law. In short, we are “justified” (made righteous) by the grace of God alone, not through any work that we ourselves do.

This, of course, was a doctrine that was born in controversy. Paul first articulates this paradox in a polemical argument in Galatia, where it seems that fervent advocates for the Gospel were maintaining that it was only by full and complete adherence to the Law that a person was able to be made righteous. Paul is incredibly snarky about this; he says such people are not “of God” (Gal 1:11–12), they are preaching “another Gospel” (1:6), that nobody is ever made righteous by the Law (3:11), and that relying on the Law is akin to being accursed (3:10).

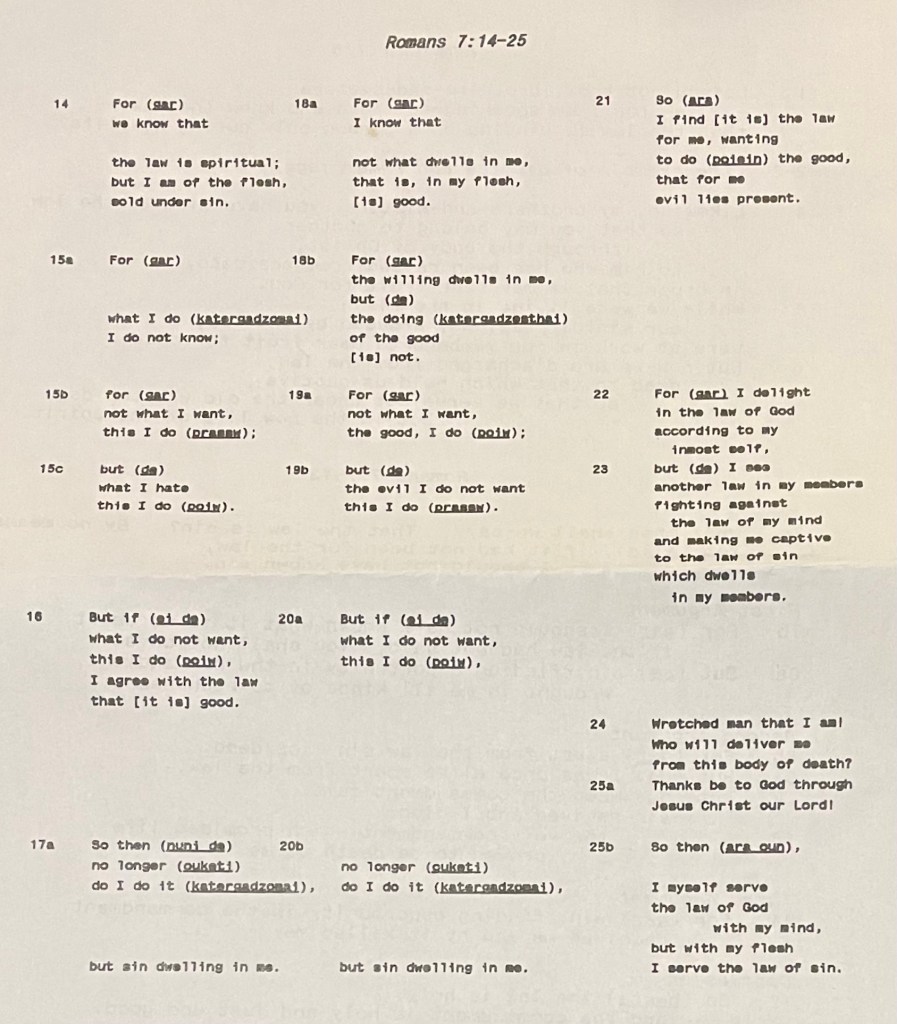

This polemic continues in the later letter to the Romans, although in this letter Paul seeks to argue the case step by step, rather than simply call his opponents names. He sets out the theme of God’s righteousness (Rom 1:16–19), explains how this process is not dependent on the Law (3:21–26), calls on Abraham as a key example for the process of being made righteous apart from the Law (4:1–25), argues that Christ fulfils the Law (10:4; 13:8–10), and deals in detail with how the people who do depend on the Law are still integral to God’s plan of salvation (9:1—11:32). See more at

The significance of this letter can be seen in the fact that it is placed first in the collection of letters by Paul—in a sense declaring that “this exposition of the argument is the lens through which all other letters should be read and understood”. Its significance was recognised, in the 2nd century, by Marcion of Sinope, who recognised Paul as THE Apostle and excised all other letters from his version of the New Testament (as well as three of the four Gospels).

In response, Jewish Christians rejected Paul and his letters. Another form of marginalising his letters took place amongst eastern believers, leading to an emphasis in Orthodoxy on John’s Gospel—it was only the “mystical” aspects of Pauline theology which they utilised in their theological schema.

Paul’s letter to the Romans was a strong influence on Augustine, both in leading to his conversion, and in providing the foundations for developing his theological position, especially in relation to “original sin”. Rom 13:11–14 was the passage that led the young libertine Augustine to adopt an ascent in lifestyle and embrace Christ: “let us walk decently, as in the daytime, not in partying and drunkenness, not in sexual immorality and sensual indulgence, not in fighting and jealousy, but put on the Lord Jesus Christ and make no provision for the desires of the flesh”. (See Augustine, Confessions, 8:29.)

It was Augustine’s distinctive interpretation of just one small phrase in Rom 5:12 that undergirded his view on the original sin of all human beings, born into depravity and needing the grace of God to be saved. Pelagius remonstrated with him, saying “you undermine the moral law by preaching grace”; Augustine countered with detailed exposition of Pauline theology, grounded in his understanding of Romans. See my discussion of this at

In the preface to his (unfinished) commentary on Romans, Augustine wrote that God’s grace “is not something that is paid in justice like a debt contracted. No, it’s a free gift … Paul preached that [the Jews] should believe in Christ, and that there was no need to submit to the yoke of carnal circumcision.”

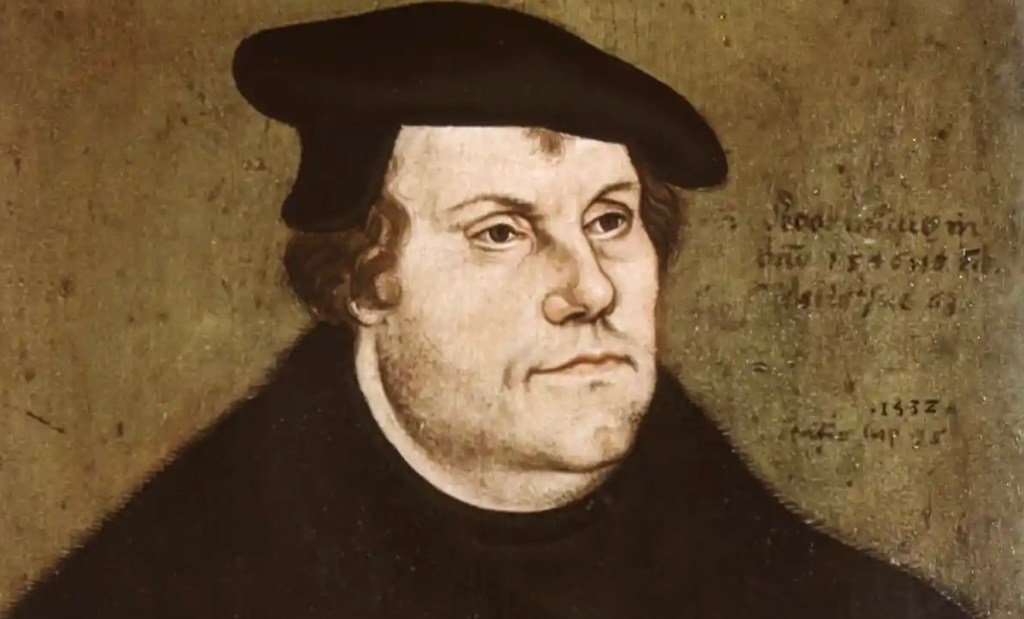

Paul’s letter to the Romans, along with his letter to the Galatians, was a key element in the argument that Martin Luther mounted against the church of his day, as he criticised the doctrines and practices of medieval Catholicism and paved the way for the German Reformation of the church.

When Luther was teaching on Paul’s letter to the Romans in 1513–1516, he had a dramatic experience: “‘I felt that I was altogether born again and had entered paradise itself through open gates.’ This new understanding of this one verse—Rom 1:17— changed everything; it became in a real sense the doorway to the Reformation. ‘Thus that place in Paul was for me truly the gate to paradise,’ says Luther (Latin Writings, 336–337).”

Luther’s argument that righteousness is a gift which God gives by grace from faith in Jesus Christ, and not something earned or merited through human religious and moral performance, has influenced both how Paul has been viewed throughout the ensuing centuries, and also how many Protestant theologians viewed Catholicism. It led to the development of what has been called the “introspective conscience” of modernity, in distinction from the strongly collectivist understandings that more recent interpreters see at work in Paul’s writing.

Photograph: Ullstein Bild/Getty

In his commentary on Romans, Luther wrote, “It [Romans] is the true masterpiece of the New Testament, and the very purest Gospel, which is well worthy and deserving that a Christian man should not only learn it by heart, word for word, but also that he should daily deal with it as the daily bread of men’s souls. For it can never be too much or too well read or studied; and the more it is handled the more precious it becomes, and the better it tastes.”

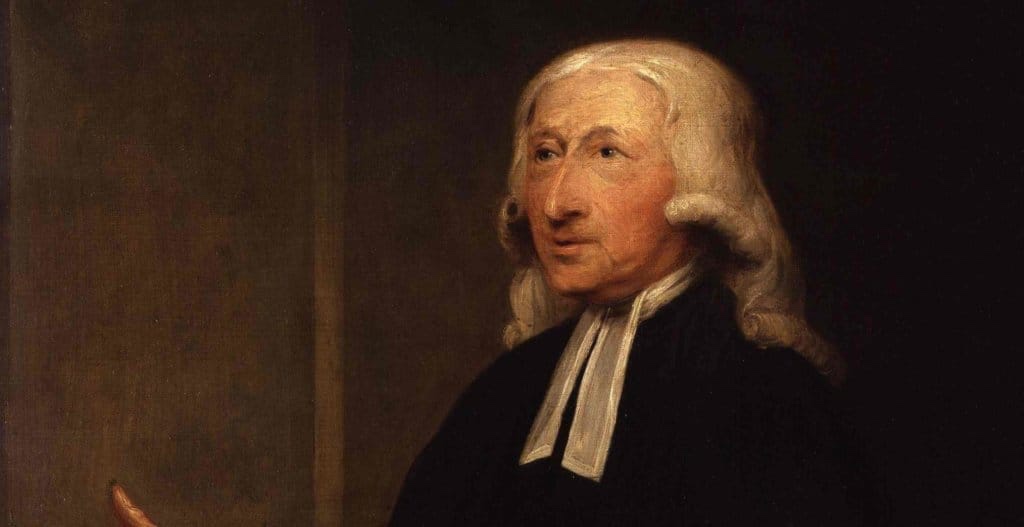

Two centuries later, on May 24, 1738, John Wesley was attending an evening service at Aldersgate Street in London. Part of Martin Luther’s commentary on Romans was read aloud. Wesley remembers, “He was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ. I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone, for my salvation; and an assurance was given me that he had taken my sins away, even mine; and saved me from the law of sin and death” (John Wesley, Works (1872), volume 1).

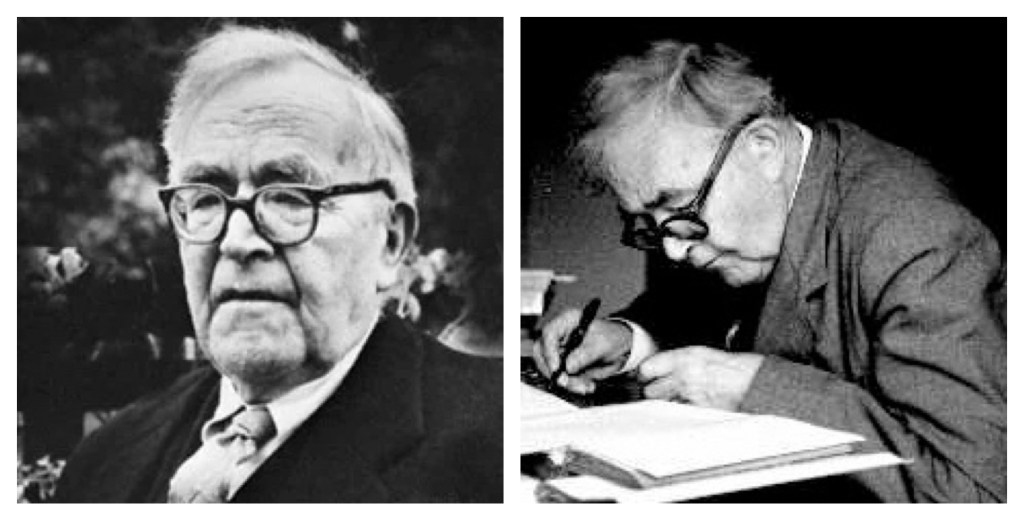

The letter to the Romans has also played a key role in the theological development of Karl Barth, the most prolific and probably most influential theologian of the 20th century. In the summer of 1916, Barth decided to write a commentary on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans as a way of rethinking his theological inheritance. The work was published in 1919; a second edition, with many revisions, followed in 1922.

This work, like many of his others, emphasizes the saving grace of God and the complete inability of human beings to know God outside of God’s revelation in Christ. Specifically, Barth argued that “the God who is revealed in the cross of Jesus challenges and overthrows any attempt to ally God with human cultures, achievements, or possessions”.

Barth led the attack on Protestant Liberalism, which in his view had held an impossibly optimistic view of the human condition and of the possibility of universal salvation. Romans was key to Barth’s creation of Neo-Orthodoxy and his insistence that Christianity was not a human religion, but a divine revelation. And that set the parameters for a key theological debate throughout the 20th century.

Phew! That’s an awful lot of influence for just one letter! We might be leaving Romans behind in the weekly lectionary offerings; but it is certain that the influence of Paul’s letter to the Romans continues apace, influencing our theology—whether we are aware of that, or not!

(And, yes, I know that this is a string of men interpreting what men have written and said … perhaps someone needs to explore and discover how a number of women have received and understood and used this letter?)

*****

For my string of exegetical posts about Romans that I have posted throughout Year A, see https://johntsquires.com/2023/09/18/ruminating-on-romans/