“They took Jesus to the high priest; and all the chief priests, the elders, and the scribes were assembled” (Mark 14:53). That’s how the author of the good news of Jesus the chosen one reports the scene when the fate of Jesus is sealed (Mark 14:53–65). Accused of predicting that the Temple would be destroyed (14:58), Jesus is interrogated by the high priest (14:60–63) before the declaration is made: “you have heard his blasphemy!” (14:64).

After further consultation by the chief priests “with the elders and scribes and the whole council”, Jesus is led away to Pilate, the Roman Governor (15:1). And so the fateful course of events is set in motion—questioned by Pilate, sentenced to be crucified, nailed to a cross where he dies, and the the lifeless body of Jesus is handed over to some of his followers (15:2–47).

The other evangelists follow suit. One notes that “the assembly of the elders of the people, both chief priests and scribes, gathered together, and they brought him to their council” (Luke 22:66), another specifies that “they took him to Caiaphas the high priest, in whose house the scribes and the elders had gathered” (Matt 26:57). The fourth gospel reports that “first they took him to Annas, who was the father-in-law of Caiaphas, the high priest that year” (John 18:13), and subsequently “Annas sent him bound to Caiaphas the high priest” (John 18:28).

The account of the time that Jesus spent being interrogated by them Jewish leadership appears, on the surface, to be an objective account of what transpired in that meeting. The council was the Great Sanhedrin, the supreme religious body in Israel during the Second Temple period—from the time when the exiles returned to the land under Nehemiah, until the destruction of the Temple in the year 70 CE. See more at https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-sanhedrin

The source of the narrative in Mark 14 is unclear; indeed, the narrator has emphasised just before reporting on this meeting that when Jesus was seized in the garden by “a crowd with swords and clubs [who had come] from the chief priests, the scribes, and the elders” (14:43), after a token display of resistance (14:47), “all [of his followers] deserted him and fled” (14:50).

The narrator underscores this with a tantalising glimpse of the figure whom I (anachronistically) call “the first Christian streaker”— “a certain young man [who] was following him” who escaped the grasp of those in the crowd, shedding his linen cloth, “and “ran off naked” (14:51–52). And Peter, most pointedly, was outside the chamber, warming himself by the fire (14:54), and denying that he even knew Jesus—not once, but three times (14:68,70,71). There was nobody—absolutely nobody—from amongst the followers of Jesus who was present to witness what transpired as Jesus was brought before “the chief priests and the whole council” (14:55).

So how do we know what happened in that council meeting?

Further exploration of the scene is warranted. Such further examination might well consider some key factors. When did the council meet? Where did they meet? How did they conduct their business? And how did they come to a decision about Jesus?

To guide any exploration of these matters, scholars have turned—with due caution—to a Jewish text which sets out the designated procedures for a meeting of the Jewish council at which serious matters such as blasphemy were considered. The due caution is warranted, because the text is found in the Mishnah, a document written early in the third century CE—thus, almost 200 years after the time when Jesus was said to have been brought before the council. Did the provisions of this 3rd century text apply in the 1st century?

dated to the 10th or 11th centuries CE.

And such caution is intensified by the fact that the Mishnah is written at a time long after most Jews had been expelled from Jerusalem. This expulsion was finalised during the abortive uprising by Bar Kochba in 132–135 CE. Indeed, the book was written well after the time when the Sanhedrin had ceased to function as the peak legislative and judicial body in Jerusalem. After the failed war against the Romans of 66—74 CE, there was no longer any such body operating in Jerusalem. Yet 150 years later, a text was written that set out specific details of how the council was to function.

So some interpreters claim that this account is simply to be seen as an idealistic, romanticised recreation of “how things used to be”, expressed in such a way that is oblivious to the reality of the time—that there was no longer a functioning Sanhedrin in Jerusalem.

Alongside these notes of caution, we must hear also the claim that is made, not just about this text, but about many texts within the body of rabbinic literature that survives, from first through to sixth centuries. That claim is that, in an oral culture such as Second Temple Judaism and Rabbinic Judaism, where stories and laws and prescriptions and debates were passed on by word of mouth, from teacher to student, from that student to their student, and so on—the reliability and historical validity of what is written can be assessed positively.

For a more detailed discussion of the oral Torah, see https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-oral-law-talmud-and-mishna

For myself, given what I have learnt in recent years about the importance and validity of stories and laws passed on over time in the oral cultures of First Nations peoples in Australia, I am inclined to accept this positive assessment of the ancient Jewish oral traditions in general, although specific texts are always open to informed critical exploration of their details.

I’m aware also, from discussions that have happened in the Uniting Church Dialogue with Jewish People that Elizabeth and I were members of for some years, that many rabbis today, who know their sacred texts well, consider that the Gospel narratives about this scene cannot be historical—for reasons that will be explored in what follows.

So, what does this text from the Mishnah say about a council meeting called to interrogate a possible criminal, such as we find in the Gospel narratives about Jesus? The relevant passages are in chapters 4 and 5 of tractate Sanhedrin, a part of the fourth order, Nezikin, which deals with Jewish criminal and civil law and the Jewish court system. And a comparison between the Gospel narratives and the Mishnah provisions raises a number of problems.

At night

The first matter is that the meeting with Jesus took place at night. Earlier, the narrator of Mark’s account has reported that the disciples “prepared the Passover meal; when it was evening, he came with the twelve” (14:16–17). Some hours later, after Jesus is apprehended in the Garden, he is taken to “the high priest … the chief priests, the elders, and the scribes” (Mark 14:53). It is still night when that meeting takes place. After coming to their decision that Jesus was “deserving death”, (14:64), the narrator notes that “as soon as it was morning, the chief priests held a consultation with the elders and scribes and the whole council” (15:1a).

So this meeting took place at night. But Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:1 states, “in cases of capital law, the court judges during the daytime, and concludes the deliberations and issues the ruling only in the daytime.” A court meeting at night, to determine a matter in which a person is determined to be “ deserving death”, is contrary to this provision.

The same section of the Mishnah also states that “in cases of capital law, the court may conclude the deliberations and issue the ruling even on that same day to acquit the accused, but must wait until the following day to find him liable” (Sanhedrin 4:1). Coming to a decision of guilty in the same session as the evidence is heard, without an overnight pause for the members of the council to consider, was also contrary to what was required. In the case of Jesus, this provision has been breached.

On a feast day

A second matter is that the meeting with Jesus took place during a festival. The whole sequence of events begins “on the first day of Unleavened Bread, when the Passover lamb is sacrificed” (14:12). At the end of their interrogation of Jesus, the narrator notes that “they bound Jesus, led him away, and handed him over to Pilate” (15:1b), and then observes that “at the festival he used to release a prisoner for them, anyone for whom they asked” (15:6).

Again, the provisions in Sanhedrin 4:1 state that “since capital cases might continue for two days, the court does not judge cases of capital law on certain days, neither on the eve of Shabbat [Sabbath] nor the eve of a Festival.” So the Markan narrative is in breach of this provision as well, by reporting that this meeting took place during Passover.

In the lack of evidence for this custom of releasing a prisoner at Passover, see more at

In the house of Caiaphas

Where exactly did this interrogation of Jesus take place? The implication in Mark is that the council was meeting in the house of Caiaphas. “Peter had followed him at a distance, right into the courtyard of the high priest; and he was sitting with the guards, warming himself at the fire” (14:54). This implication is made explicit at Matt 26:57 (“they took him to Caiaphas the high priest, in whose house the scribes and the elders had gathered”) and Luke 22:54 (“bringing him into the high priest’s house”).

Once more, this flies in the face of the prescriptions of tractate. Later in the tractate Sanhedrin, there is a reference to “the Sanhedrin of seventy-one judges that is in the Chamber of Hewn Stone” (Sanhedrin 11:2). This means the meeting should have taken place in this part of the Temple; in the Babylonian Talmud, it is stated to have been in the north wall (b.Yoma 25a). The Gospel narratives locate the meeting with Jesus in the house of the high priest; this is a third breach of the Mishnaic provisions.

The witnesses did not agree

A fourth issue is the observation that Mark makes and then repeats, that “many gave false testimony against him, and their testimony did not agree. Some stood up and gave false testimony against him … even on this point their testimony did not agree” (14:56–59).

Tractate Sanhedrin requires a verdict to be made only if the witnesses are in agreement, declaring, “At a time when the witnesses contradict one another, their testimony is void” (Sanhedrin 5:2). In a later rabbinic text, the Talmud, this requirement is expanded: “afterward they bring in the second witness and examine him in the same manner. If their statements are found to be congruent the judges then discuss the matter” (b.Sanhedrin 29a). This clearly did not occur in the case of Jesus.

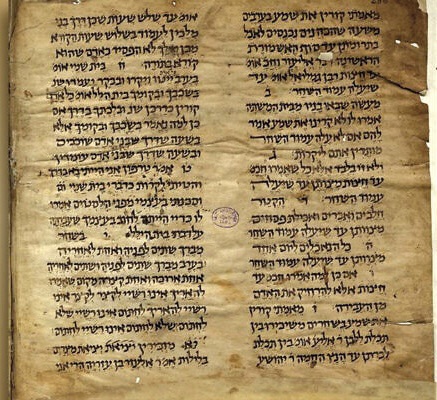

the central text of Mishnah (in large print)

is then commented upon in Gemara (in medium print)

and later medieval notes (in small print)

surround these in the margins.

These various matters would seem, on the surface, to indicate that the members of the council were so panicked by Jesus that they acted to condemn him with flagrant disregard for their own provisions—assuming that the later text of the Mishnah does, in fact, describe the requirements in place in the first century.

An alternative explanation is that the narrative was compiled by someone who was ignorant of these provisions, and they simply “made up” a narrative which demonstrated the desperation of the Jewish authorities to deal with Jesus and have him out of the way.

We should place this view alongside the observation that the narratives in the Gospels take a number of steps to minimise the blame that Pilate must bear for sentencing Jesus to he crucified.

On the flawed picture of Pilate in the Gospels and the implausibility of the role assigned to him in these accounts, see

Minimising the culpability of the governor of the imperial power in these events, and strengthening the role of the Jewish authorities, go hand-in-hand. A clear apologetic purpose is at work in this narrative. It made sense for the narrator to avoid further condemnation by Rome, which held continuing power during the time he was writing, and to magnify the blame of the Jewish authorities, with whom the fledgling movement of followers of Jesus had been in increasing tension and conflict.

In other words, the narrative of this trial before the Sanhedrin is both historically implausible, and apologetically purposeful, as it shifts the blame for sentencing Jesus more onto the Jewish authorities than on Pilate. And in a later scene, it is the Jewish crowd which calls for Pilate to hand down the sentence of death (“crucify him! crucify him!”, 15:13–14). That is a most unlikely occurrence, indeed.

And so another element grew in the developing Christian ideology which placed the blame for the death of Jesus on the Jewish authorities (and sadly, in later centuries, on “the Jews” themselves). It is a view that we would do well to reject.

See also