The pair of passages from Genesis proposed by the Narrative Lectionary for this coming Sunday contain a paradox. On the one hand, after years of Abraham and Sarah yearning in vain for a son, “the Lord did for Sarah as he had promised; Sarah conceived and bore Abraham a son in his old age” (Gen 21:1–2). The son was named Isaac, meaning laughter; as Sarah, aged 100, declares, “God has brought laughter for me; everyone who hears will laugh with me” (21:6).

Yet in the second passage offered by the lectionary, we read some chilling words: “Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to kill his son” (Gen 22:10). How does this relate to the joy seen at the birth of Isaac? There is no laughter in this story. It’s a horrifying story. How is this edifying material for hearing in worship?

Questions abound. Who is this God who calls Abraham to take his “only son” up the mountain and “offer him there as a burnt offering” (22:2)? Where is the God who, it is said, has shown “steadfast love” to the people of Israel (Exod 15:13), and before that to Joseph (Gen 39:21), to Jacob (Gen 32:9–19), and indeed to Abraham himself (Gen 24:27)? Why has God acted in a way that Is seemingly so out of character in this incident in Gen 22? Or is this the real nature of God, and these later displays of “steadfast love” are simply for show?

This story is indeed troubling: it presents a God who demands a father to kill his beloved son, with no questions asked. It is not just the knife in Abraham’s hand which is raised (22:10)—there are many questions raised by this seemingly callous story.

My wife, Elizabeth Raine, has a cracker of a sermon in which she compares this story with the account of Jephthah and his daughter (Judg 11:29–40). Whilst the Lord commands Abraham to kill his son as a burnt offering, it is the vow made by Jephthah to sacrifice “whoever comes out of the doors of my house to meet me, when I return victorious from the Ammonites” as a burnt offering (Judg 11:30).

And whilst the Lord intervenes in what Abraham is planning to do at the very last moment, sending an angel to command him, “do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him” (Gen 22:11–12), Jephthah is held to the vow he has made—by his very own daughter, who knows that she will be the victim of this vow (Judg 11:39). There is no divine intervention in this story.

And worse, whilst Abraham had carefully prepared for the sacrifice, taking his donkey, two servants, and the wood for the fire up the mountain with him (Gen 22:3–6), Jephthah’s vow was made on the spur of the moment (Judg 11:30–31), and when his daughter insisted that he must carry through with this vow, he gives her, as requested, two full months for her to spend with her companions before he sacrificed her (Judg 11:37–39). Surely he might have had time in those two months to reconsider his vow and turn away from sacrificing his daughter?

It would seem, then, that the daughter was dispensable; the son, the much loved only son of Sarah and Abraham, was clearly indispensable. That would clearly reflect the values of the patriarchal society of the day, in which “sons are indeed a heritage from the Lord, the fruit of the womb a reward” (Ps 127:3).

And Abraham would have followed the same pathway, sacrificing his only son, had not the Lord intervened. Neither father is looking very appealing in these two stories! Which makes it hard to see how the story of the sacrifice told in Judg 11, and the story of the almost-sacrifice told in Gen 22, can be “the word of the Lord” for us, today, in the 21st century. Indeed, the story of Abraham and Isaac comes perilously close to being a story of child abuser—if not physical abuse, by the end of the story, at least emotional and spiritual abuse.

Situations of abuse destroy trust. After such an experience, how could Isaac ever trust his father again? And as we hear the story, how can we trust God? How could we ever believe that his commands to us are what we should follow?—if he follows the pattern of this story, and changes his mind at the last minute, after pushing us to the very brink of existence? How could we trust a God like this?

Or, if the story involving poor Isaac is really about God providing, as Abraham intimates early on (22:8), and then concludes at the end (22:14), then it is a rather malicious way for God to go about showing how he is able to “provide”. Provision, and providence, should be something positive—not perilous and threatening, as in this story.

Or yet again, if the story is about testing Abraham’s faith, as many interpreters conclude, then it is a particularly nasty and confronting way for God to do this—and that points to a nasty streak in the character of God. Is this really what we want to sit with? Was there not some other way for God to push Abraham to test his faith?

What do we do with such a story within our shared sacred scriptures?

The Jewish site, My Jewish Learning, states that “although the story itself is quite troubling, it does contain a message of hope for Rosh Hashanah. In the liturgy we ask God to “remember us for life.” The binding of Isaac concludes with his life being spared, and he too is “remembered for life.” Abraham’s devotion results in hope for life.”

How does the message of hope for life emerge from this story? Clearly, the life of Isaac is spared; but this is a terrible way to teach that message!

James Goodman, writing in My Jewish Learning, explains how he was taught to understand this story. “I learned that the story was God’s way of proclaiming his opposition to human sacrifice”, Goodman writes.

He refers to the way his Hebrew-school teacher explained this story: “God had brought Abraham to a new land. A good and fertile land, where it was common for pagan tribes, hoping to keep the crops and flocks coming, to sacrifice first-born sons to God. Then one day, God commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac, the beloved son of his old age.

“Abraham set out to do it, and was about to, when God stopped him. He sacrificed a ram instead. In the end, Abraham had ‘demonstrated his—and the Jews’—heroic willingness to accept God and His law,’ and God had ‘proclaimed’ that ‘He could not accept human blood, that He rejected all human sacrifices’.”

See https://www.myjewishlearning.com/2013/09/11/understanding-genesis-22-god-and-child-sacrifice/

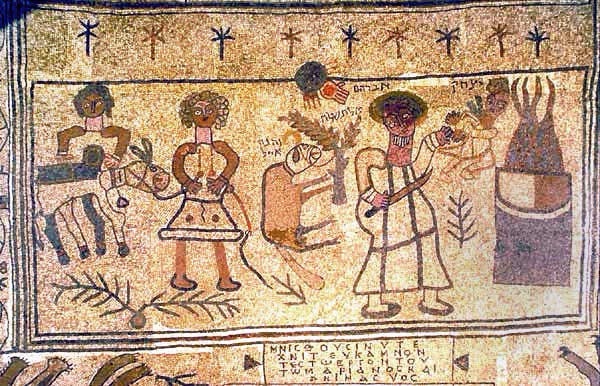

Setting the story in the broader context of the practice of child sacrifice is a way of accepting that this terrible story might indeed have some value. Seeing the story is a dramatised version of God’s command not to sacrifice children can be a way to deal with it. “Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him”, the angel says; so Abraham obeys, finds a ram, offers the ram as a burnt offering (22:12–13). And so, the name of the place is given: “the Lord will provide”(22:14).

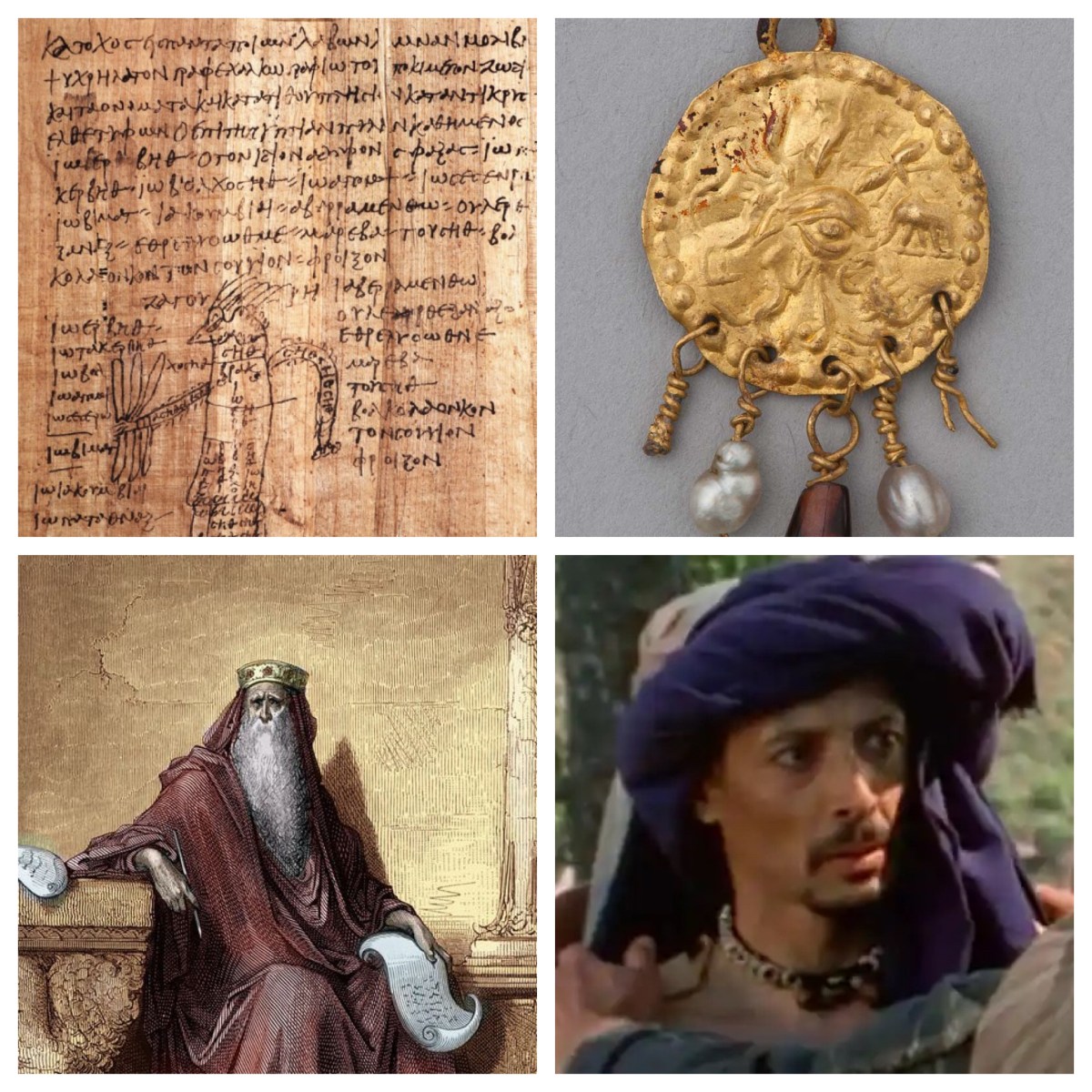

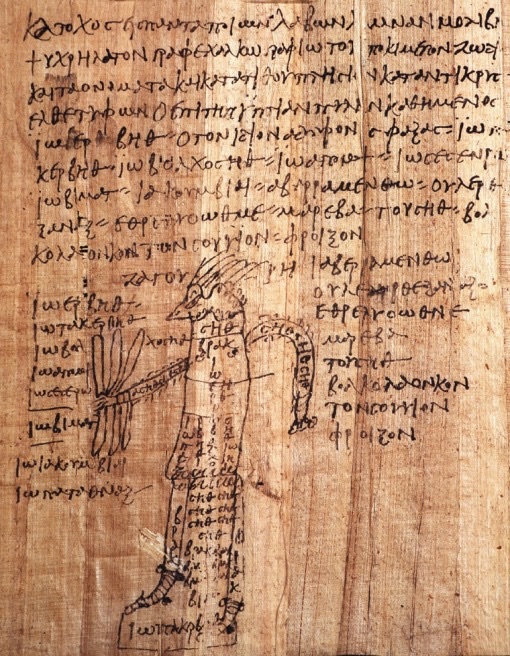

Three kings of Israel, at different times in the history of Israel, are said to have practised child sacrifice, as they turned to practices found in nations other than Israel. Solomon in his old age is said to have turned to the worship of Molech (1 Ki 11:7); this practice was subsequently adopted by Ahaz, who “made offerings in the valley of the son of Hinnom, and made his sons pass through fire, according to the abominable practices of the nations whom the Lord drove out before the people of Israel” (2 Chron 28:3). Likewise, Manasseh “made his son pass through fire; he practiced soothsaying and augury, and dealt with mediums and with wizards” (2 Ki 21:6).

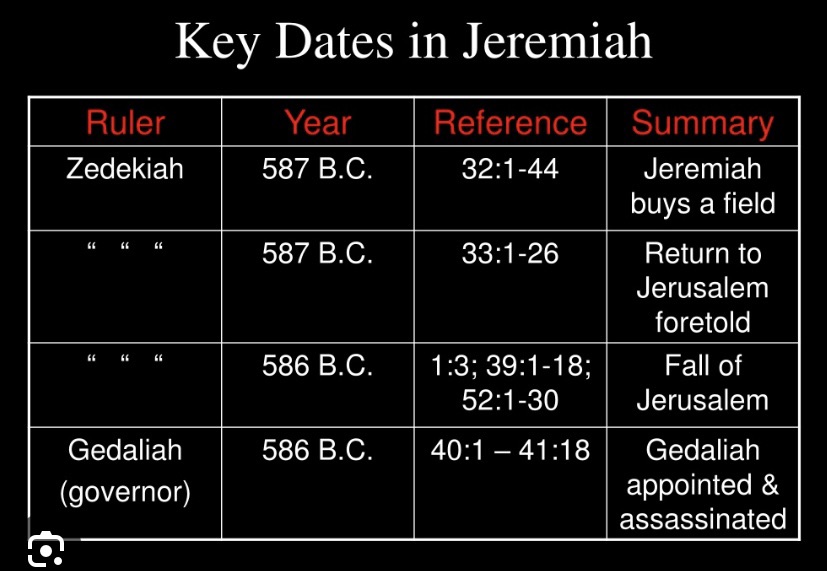

Direct commands not to sacrifice children are found in two books of Torah in the scriptural texts. Most direct is “you shall not give any of your offspring to sacrifice them to Molech, and so profane the name of your God: I am the Lord” (Lev 20:18). In Deuteronomy, other nations are condemned as they “burn their sons and their daughters in the fire to their gods” (Deut 12:31), so the command is “no one shall be found among you who makes a son or daughter pass through fire” (Deut 18:10). The prophet Jeremiah also asserts that this practice is not something that the Lord God had thought of (Jer 7:31).

So the passage we have in the lectionary responds to this practice by telling a tale which has, as its punchline, the command “do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him” (22:12). Might this be the one redeeming feature of this passage?

But if that is the case, the story belongs back in the days when child sacrifice was, apparently, widely practised. What, then, does it say to us today??