We have been hearing a sequence of passages from 1 Peter which the lectionary offers during this Easter season. This week the passages selected from the latter part of the letter contain a series of verses that provide assorted exhortations and instructions to those who first received this letter (1 Pet 4:12–14; 5:6–11). The first of these two passages contains a wealth of riches; in this blog I will focus only on those three verses.

This section of the letter begins with encouragement (v.12), moves to offer an affirmation (v.13), returns to a word of encouragement (v.14a) and then offers a blessing to those who have received this letter (v.14b). Those recipients, as we have earlier seen, were “exiles of the Dispersion” in the five Roman provinces of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia (1:1), so the presence of scriptural quotations and allusions in this letter is no surprise.

However, a number of verses indicate that there would also have been Gentiles in their midst (2:12; and see my earlier posts on the “household table” of 2:18–3:7). Accordingly, the exhortations and instructions draw on both Israelite and Greco-Roman ethics. My focus in this blog is on the scriptural resonances in what is here written.

This short passage (4:12–14) is introduced by the words, “Beloved, do not be surprised at the fiery ordeal that is taking place among you to test you” (4:12), before moving to an affirmation, “be glad and shout for joy” (4:13) and a blessing, “if you are reviled for the name of Christ, you are blessed” (4:14).

The “fiery ordeal” in that initial exhortation reflects the common prophetic depiction of divine judgement which would be experienced as a searing fire. Isaiah warns that the Lord executed judgement in his time by fire: “wickedness burned like a fire, consuming briers and thorns; it kindled the thickets of the forest, and they swirled upward in a column of smoke; through the wrath of the Lord of hosts the land was burned, and the people became like fuel for the fire; no one spared another” (Isa 9:18–19).

This fiery image was provided by the very actions of the invaders: “your country lies desolate, your cities are burned with fire; in your very presence aliens devour your land; it is desolate, as overthrown by foreigners” (Isa 1:7). Accordingly, the godless ask, “who among us can live with the devouring fire? who among us can live with everlasting flames?” (Isa 33:14), whilst the prophet pleads, “let the fire for your adversaries consume them” (Isa 26:11).

Jeremiah describes how the Lord God called him: “I have made you a tester and a refiner among my people so that you may know and test their ways … the bellows blow fiercely, the lead is consumed by the fire; in vain the refining goes on, for the wicked are not removed” (Jer 6:28–29). This description was also shaped, no doubt, by the actions of the invaders: “the Chaldeans who are fighting against this city shall come, set it on fire, and burn it, with the houses on whose roofs offerings have been made to Baal and libations have been poured out to other gods, to provoke me to anger” (Jer 32:29).

Ezekiel also predicts fiery carnage: “you shall take some, throw them into the fire and burn them up; from there a fire will come out against all the house of Israel” (Ezek 5:4; also 15:1–8; 19:12–14). God warns Israel, “you shall be fuel for the fire, your blood shall enter the earth” (Ezek 21:32); in a dramatic oracle, the prophet describes the gruesome fate of the people: “Woe to the bloody city! I will even make the pile great. Heap up the logs, kindle the fire; boil the meat well, mix in the spices, let the bones be burned. Stand it empty upon the coals, so that it may become hot, its copper glow, its filth melt in it, its rust be consumed. In vain I have wearied myself; its thick rust does not depart. To the fire with its rust!” (Ezek 24:9–12).

The author of Lamentations describes how God “has cut down in fierce anger all the might of Israel; he has withdrawn his right hand from them in the face of the enemy; he has burned like a flaming fire in Jacob, consuming all around” (Lam 2:3). Other prophetic references to the fire of judgement include Hos 8:14; Joel 1:19–20; 2:3–5; Amos 1:4, 7, 10, 12, 14; 2:2, 5; 5:6; Obad 1:18; Mic 1:2–7; Nah 1:6; 3:15; Zeph 1:18; Zech 2:5; 9:4. Most famously, in the predictive oracle of Malachi, the prophet looks to the coming day of the Lord’s messenger: “he is like a refiner’s fire and like fullers’ soap; he will sit as a refiner and purifier of silver, and he will purify the descendants of Levi and refine them like gold and silver” (Mal 3:1–3).

It is no surprise, then, that many psalms reflect on the use of fire to signal divine displeasure: “the voice of the Lord flashes forth flames of fire” (Ps 29:7), “on the wicked he will rain coals of fire and sulfur” (Ps 11:6), “as as wax melts before the fire, let the wicked perish before God” (Ps 68:2). Fire is listed along with hail, snow, frost, and stormy wind as “fulfilling [God’s] command” (Ps 148:8) and the psalmist affirms that “you make the winds your messengers, fire and flame your ministers” (Ps 104:4).

The vengeance of God is indeed a fearful sight. “Smoke went up from his nostrils, and devouring fire from his mouth; glowing coals flamed forth from him … he made darkness his covering around him, his canopy thick clouds dark with water; out of the brightness before him there broke through his clouds hailstones and coals of fire” (Ps 18:8–12). The psalmist pleads, seemingly in vain, “How long, O Lord? will you be angry forever? will your jealous wrath burn like fire?” (Ps 79:5; also 89:46).

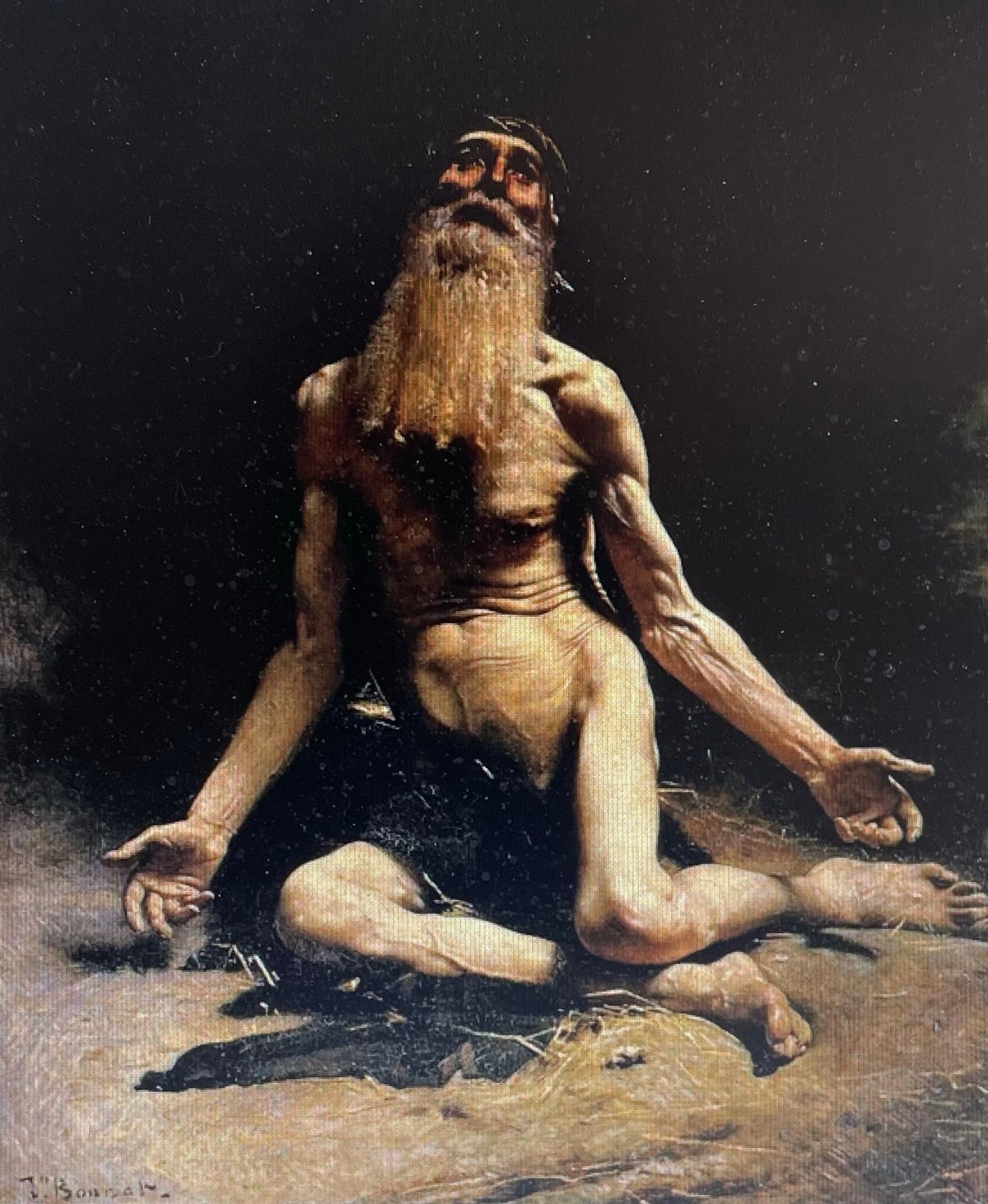

This rhetoric of the “fiery ordeal” in 1 Pet 4:12 is potent language, reminding the Jews of the Diaspora of the power that God has exercised in the past, and presumably is once again manifesting in the troubling experiences of their present. That ordeal has certainly brought suffering to the people; the suffering which was being experienced by believers is a constant refrain in this letter. It is noted briefly in the opening blessing (1:6–7) and described in more detail on a number of other occasions.

*****

So, in the midst of this “fiery ordeal”, the author encourages those hearing this letter to “endure pain while suffering unjustly” (2:19–20) and says to them that “it is better to suffer for doing good, if suffering should be God’s will, than to suffer for doing evil” (3:13–17); “whoever has suffered in the flesh has finished with sin” (4:1–2); “let those suffering in accordance with God’s will entrust themselves to a faithful Creator, while continuing to do good” (4:12–19); and “you know that your brothers and sisters in all the world are undergoing the same kinds of suffering” (5:6–11).

In addressing this suffering, as we have noted, the writer offers an affirmation (4:13) and a blessing (4:14). Both affirmation and blessing sound very much like sayings of Jesus which form part of his famous Beatitudes, at Matt 5:11–12 and its parallel in Luke 6:22–23. In these sayings, Jesus refers to shouting for joy in the midst of sufferings, which resonates with the message that is set out throughout this letter.

Joy and suffering are linked in the affirmation, “rejoice insofar as you are sharing Christ’s sufferings, so that you may also be glad and shout for joy when his glory is revealed” (4:13). Being blessed is connected with being reviled in the blessing, “if you are reviled for the name of Christ, you are blessed” (4:14). They both evoke the words of Jesus, “blessed are you when people hate you, and when they exclude you, revile you, and defame you on account of the Son of Man; rejoice in that day and leap for joy” (Luke 6:22–23).

The letter continues with the statement that “the spirit of glory, which is the Spirit of God, is resting on you” (4:14). This reflects the prophetic understanding of the spirit resting on people: “the shoot shall come out from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots; the spirit of the Lord shall rest on him, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and the fear of the Lord” ( Isa 11:1–2); or “the spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me” (Isa 61:1).

This dynamic is also reflected in passages about leaders in Israel, recounted in narrative books, as the Spirit comes upon the seventy elders (Num 11:25), Balaam (Num 24:2), the judges Othniel (Judg 3:10) and Jephthah (Judg 11:29), the kings Saul (1 Sam 11:6) and David (1 Sam 16:13), and the chosen Servant (Isa 42:1). The Spirit came onto the messengers of Saul and led them into a prophetic frenzy (1 Sam 19:20).

Others who experienced the alighting of the Spirit included the little-known Amasai (1 Chron 12:18), Azariah son of Oded (2 Chron 15:1), and Jahaziel son of Zechariah (2 Chron 20:14), each of whom are reported as having spoken words from the Lord after that experience.

During the trials and difficulties of the Exile, the Spirit inspired the words of the priest Ezekiel, son of Buzi (Ezek 3:14; 11:5) and later inspired the unnamed post-exilic prophet to speak the oracles collected in Isa 56—66 (see Isa 59:21; 61:1). The prophets look for the outpouring of the Spirit to come upon “the house of Israel” (Ezek 39:29), upon the descendants of the house of Jacob (Isa 44:1–3), to enable them to live faithfully once more in the land (Ezek 36:26–28; and then in the famous vision of dry bones, Ezek 37:12–14).

This mirrors the experience of the people of Israel as they wandered for forty tears in the wilderness, for the Lord God “gave your good spirit to instruct them, and did not withhold your manna from their mouths, and gave them water for their thirst” whilst the people of Israel were in the wilderness (Neh 9:20; see also Isa 63:13–14).

Indeed, the retreat from Judah of the aggressors sent by King Sennacherib of Assyria was due to the fact that the Lord “put a spirit in him, so that he shall hear a rumor, and return to his own land; I will cause him to fall by the sword in his own land” (Isa 37:5–7).

So to say that “the spirit of glory, which is the Spirit of God, is resting on you” (1 Pet 4:14) is a very strong statement of affirmation for the recipients of this letter!