Elizabeth and I have just attended the Closure of Ministry service at which the Rev. Jane Fry concluded her years of service as the Secretary of the Synod of NSW.ACT—or, as Elizabeth referred to it, the Synod of the ACT and NSW (ever loyal to our time in the Canberra Region Presbytery!)

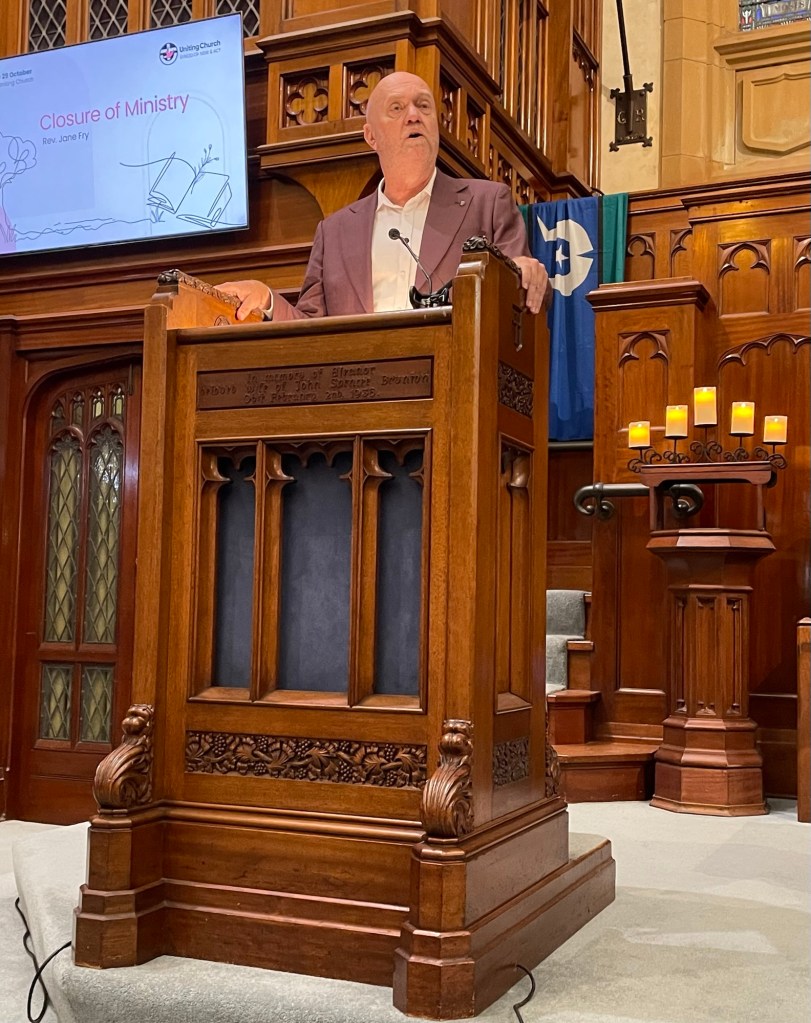

It was held in the impressive surroundings, dripping with signs and symbols of Christendom, in St Stephen’s Uniting Church in Macquarie Street, Sydney, directly opposite the NSW Houses of Parliament. The team from St Stephens, under the wise and gentle leadership of Ken Day, did a fine job in hosting the crowd of people who came for this important occasion.

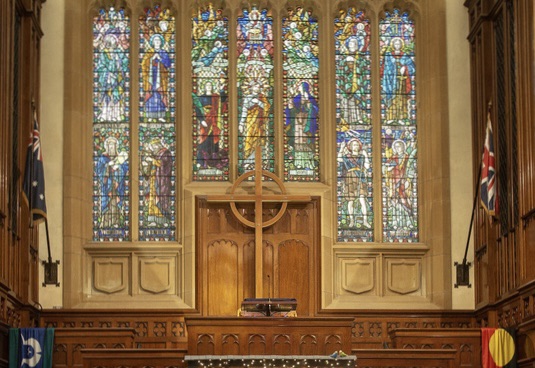

Banks of wooden pews filled the large floor area of the church, with wooden panelling running around the walls. At the front, above the high central (typically Presbyterian) pulpit, stained glass windows reached up to the high vaulted ceiling—including various Hebrew prophets and early Christian saints (including, of course, St Stephen himself). Two flags from the glory days of Church and Empire hung high at the front—the Australian Blue Ensign on the left, the British Union Jack on the right—and the respective flags of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were draped over the railings running out from the high pulpit. Rich symbolism abounded.

Our venturing all the way into the Sydney CBD for this event (170km, but who’s counting?) meant, on the one hand, that we had to endure the thick, turgid, stress-evoking traffic snarls of Sydney; nothing can be a stronger signal to Elizabeth and myself that we have made the right decision to retire in rural Dungog! Yet this visit also offered the welcome opportunity to celebrate and express gratitude for the gifts Jane has brought to this crucial leadership role, and to meet up with many people with faces and names familiar from past years (or decades)! It was good to reconnect in person with many who for some time now have been “Facebook friends”. The bonds of years past hold strong.

There were multiple conversations in the church’s Ferguson Hall in the time after worship, as we ate, drank, and caught up, under the watchful eye of the Rev. John Ferguson, after whom the hall is named. Ferguson was minister of St Stephen’s from 1894 to 1925, including a term as Moderator-General of the Presbyterian Church in Australia commencing in 1909.

Alan Dougan writes in the Australian Dictionary of Biography that “his inaugural address, published as The Economic Value of the Gospel, raised a storm in Melbourne and praise from trade union leaders. Billy Hughes said ‘The new moderator preaches a gospel all sufficient, all powerful. He grapples with the problems of poverty … he insists on justice being done, though the heavens fall. I advise every citizen to read every word of it’.”

Ferguson was a most enlightened minister, it would seem; apparently he sought an audience with the Pope on a visit to Rome in 1914, “an action that evoked much hostile criticism in Sydney”, says Dougan. The tribalism in Sydney’s ecclesial life, clearly evident in this reaction, is sadly still alive and well in this city, where sectarian fundamentalism (“We Know The Truth, and Only We Have It!”) has an iron grip in some churches. Not in the Uniting Church, however!

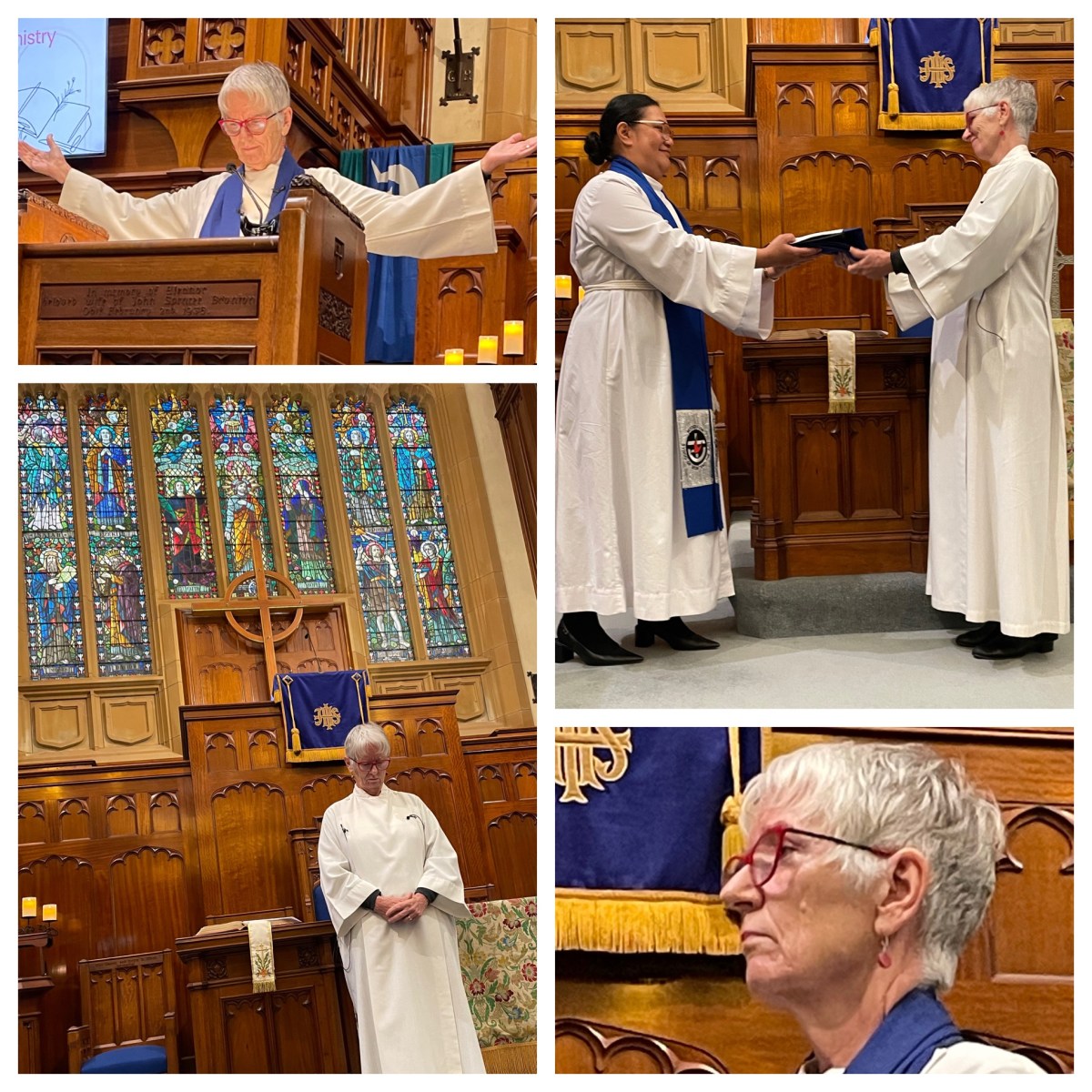

The church on this occasion held a full congregation when the service itself began, with Jane in characteristic pose, arms outstretched, as she called the people to worship: “Look! Listen!”, with a string of appropriate scripture sentence after each iteration. Nathan Tyson then acknowledged Country, giving thanks for the First Peoples who have cared for the land for millennia, and offering a gracious and warm welcome to the many Second Peoples (of multiple cultural heritages) who had gathered for the occasion.

Past Moderator Simon Hansford brought words of confession (“we speak words of cynicism and anger; for this we are sorry …”) before offering an Assurance of God’s pardon, to which we replied, “thanks be to God”. Jane and Simon had worked together as a fine set of leaders of the Synod team for six years, through the difficulties and challenges of the COVID pandemic. It was good to have his clarity of thought in these prayers of confession.

We sang a number of good hymns, including a favourite one written by Charles Wesley “a long time ago”, as wry Jane’s annotation in the order of service observed. How many people were like me: enjoying the melody and harmony of “And can it be” whilst inwardly recoiling at the blood, wrath, and divine vengeance permeating the hymn, before divine grace eventually shone through?

Yes, these words show that it was indeed “a long time ago” that such theology reigned supreme; fortunately within the Uniting Church we can see that “the Lord has yet more light and truth to break forth from his word” (in the words of John Robinson, spoken to the Pilgrims in 1620 as they departed on their journey to “the new world” in 1620, and then include in a hymn written by British Congregationalist George Rawson in the 1850s).

So it is that, as a church, we do indeed rejoice in the affirmation that we “remain open to constant reform under [God’s] Word” and that as “a pilgrim people, always on the way towards a promised goal” we are able to delve into our scripture, traditions, and heritage, “give thanks for the knowledge of God’s ways with humanity which are open to an informed faith”, “sharpen its understanding of the will and purpose of God by contact with contemporary thought”, and stand “ready when occasion demands to confess the Lord in fresh words and deeds”. (Excerpts from the UCA Basis of Union)

Neale Roberts of Uniting brought two readings from scripture, delivered with eloquence, nuance, and expression. From the scriptures we share with Jewish people he read a passage celebrating Wisdom: “When he marked out the foundations of the earth, I was there, beside him … now, then, listen to me” (Proverbs 8).

And then he read words attributed to Jesus: “do not worry about your life … look at the birds of the air … consider the lilies of the field … do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will bring worries of its own; today’s trouble is enough for today”. As Neale observed to me afterwards, “I am sure Jane picked that passage for its final words, as a word to the church today”. They do indeed encapsulate the deep faith and strong hope that Jane has always exuded.

Elizabeth Raine, friend and colleague of Jane since they first met as theological students at UTC in the early 1990s, preached the sermon. Indeed, as a personal aside, I was struck the fact that all who offered leadership in this service, apart from Nathan Tyson, had studied theology and undergone formation for ministry at UTC during the 1990s; perhaps a fine testament to the grounding they had received then—more certainly, a clear indicator of the qualities and giftedness that each person has brought to ministry over the ensuing decades. The church has benefitted much from the calling to which each of them has responded.

Elizabeth spoke about the figure of Wisdom who had been the focus of the Proverbs reading. She warned the congregation, “I told Jane I would be feral and unfiltered … and Jane said to me, ‘go for it!’” And so she did. You can read the full sermon via the link at the end of the blog, but here are some choice extracts: “Wisdom calls us on an unexpected journey … she transgresses male boundaries, standing at the street corner, raising her voice in public places … but Wisdom has been grafted on to Jesus by the early church scholars … they were consumed by their categories and systems … we emerged with a transgendered Holy Spirit … a meek, obedient virgin-mother became the model for women … the figure of Wisdom has been overshadowed.”

Elizabeth offered incisive exegetical insights into the riches that the poetic passage in Proverbs contains. concluded that Wisdom speaks to the church today; “she offers us a relational faith, listening to others, working together for the common good … anyone, but anyone, can acquire what she offers … she would undoubtedly value the invitation of Jesus to his disciples to ‘fish on the other side of the boat’, to be open to new possibilities, not to be bound to practices of the past, and to hold to a relational, experimental theology”. “How will we as a church relate to Wisdom?” she concluded.

by Sara Beth Baca; https://www.sarahbethart.com

It was clear from the many expressions of thanks—mostly, not entirely, from women in the congregation—that Elizabeth’s “unfiltered” feminist exposition of this crucial passage had struck a very positive chord for many who were present. “We need to hear this message, we need to hear your voice” was a regular refrain. Preachers and teachers in the church should take note; there is, within informed Uniting Church people, a deep appetite for substantive biblical preaching with a clear, prophetic, feminist hermeneutic that speaks directly into our situation today!

After joining in an Affirmation of Faith, we enjoyed the inspiring playing of the Stephens’ Organ Scholar, Andrei Hadap (pictured in action above), as we meditated on the delightful words of a hymn by Thomas Troeger: “how shall we love this heart-strong God who gives us everything, whose ways to us are strange and odd: what can we give or bring?” Associate Secretary of Synod Bronwyn Murphy then led the prayers of the people to this “heart-strong God”: “so much pain held within one small planet … so hear us, O God, as we pray for your earth … for all people, gathered within your welcome … for the Uniting Church, a body in transition … and for Jane and her family”.

Jane then spoke in her characteristic direct and challenging style. She referred to the “nine years of drama, change, and engagement across the church”. She is, she confessed (as if we needed reminding!) “a sceptical person, not an early adopter [who] did not expect the recent significant decisions of Synod to have been adopted!” Her reflection at this point was, once again, characteristically Jane; she saw this as an indication that “God is not done with the Uniting Church”.

She reminded all present that “the change [we have] initiated is just housekeeping. Synod is administrative, Presbytery has an oversight role, but the Congregation is where faith is nurtured”. She emphasised that the church is called to “nurture faith, form discipleship, and welcome all: these are the critical elements of being the church.” Her final word exuding the hope she has always held over the years in fulfilling her leadership roles in Congregation, Presbytery, and Synod: “neglecting the disciplines of faith is incredibly dangerous: prayer is the foundation. Letters us remember: ‘God has got this’”.

her ministry as Secretary of Synod

The Moderator, Mata Havea Hilau, then led the formal closure of ministry for Jane, offering the thanks of all present in the worship space and those participating via the livestream, and praying for Jane, “May the God who rested on the seventh day to delight in all the creation hold you in her arms as you have held this work, celebrate with us the life that takes life from you, and give you grace to let go into a new freedom”; to which all the people responded: Amen!

In the Ferguson Hall after the service, in the midst of the plethora of conversations filling the space with a cascade of sounds, Peter Walker, the incoming Secretary of Synod and former Principal of UTC (and yet another graduate of UTC from the 1990s!) presided over a brief time of formality. Jane expressed her thanks to many people who had worked alongside her and encouraged her over the past nine years. She was given a gift of a lovely bunch of native flowers.

And then the crowd dispersed, stepping back into the rain, the traffic, the chaos of everyday life … … …

*****

You can read the full text of Elizabeth’s sermon at