In the psalm that is set for the Second Sunday in Lent (a section of Psalm 22), the psalmist exults the worldwide dominion of the Lord God and sings that “to [the Lord], indeed, shall all who sleep in the earth bow down; before him shall bow all who go down to the dust, and I shall live for him” (Ps 22:29).

This psalm is best known for its opening line, “my God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Ps 22:1a), as this is the last word of Jesus as he dies on the cross, at least according to two evangelists (Mark 15:34; Matt 27:46). The psalm is one of the psalms of individual lament, as the psalmist reflects the wretched condition of a person who is suffering unjustly, as the psalmist cries, “why are you so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning? … I am a worm, and not a human … all who see me mock at me; they make mouths at me, they shake their heads …. I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint; my heart is like wax; it is melted within my breast; my mouth is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue sticks to my jaws; you lay me in the dust of death.” (Ps 22:1, 6, 14–15).

The other psalms usually considered to express individual lament reflect similar ideas: Ps 3 (“O Lord, how many are my foes! many are rising against me), Ps 6 (“be gracious to me, O Lord, for I am languishing”, Ps 13 (“how long will you hide your face from me?), Ps 25 (“I am lonely and afflicted; relieve the troubles of my heart, and bring me out of my distress”), Ps 31 (“my eye wastes away from grief, my soul and body also; for my life is spent with sorrow, and my years with sighing”), Ps 71 (“in your righteousness deliver me and rescue me; incline your ear to me and save me”), Ps 77 (“I think of God, and I moan; I meditate, and my spirit faints”), Ps 86 (“O God, the insolent rise up against me; a band of ruffians seeks my life, and they do not set you before them”), and Ps 142 (“with my voice I cry to the Lord; with my voice I make supplication to the Lord”).

However, the section of the psalm that is offered for this coming Sunday (Ps 22:23–31) comes from the second half of the psalm, where—as is typical of many psalms of lament—the mood turns from internal personal introspection, to an external offering of praise and adoration to God. In each psalm the undergirding assumption is that God does care, God will act, and the trials of the present will be swept away. They are psalms imbued both with the sober reality of the human condition, and an unswerving optimism that faith in God will ensure an ultimate condition of salvation, deliverance, redemption.

Although the psalms offered by the lectionary are chosen each Sunday to provide a companion piece to the Hebrew Scripture passage, this element of this psalm makes it a most fitting accompaniment to the Gospel passage offered this coming Sunday in Lent, as the path that Jesus walks towards the cross is in view during this season.

So the psalmist rejoices. God has dominion over the whole earth: “all the ends of the earth shall remember and turn to the Lord and all the families of the nations shall worship before him; for dominion belongs to the Lord and he rules over the nations” (vv.27–28). This affirmation reflects other parts of Hebrew Scripture where the global reach of God is asserted.

One psalmist calls the ends of the earth “the possession of the Lord” (Ps 2:8), for they “have seen the victory of our God” (Ps 98:3). Both the name and the praise of the Lord “reaches to the ends of the earth” (Ps 48:10), for when God acts to judge the nations, “the it will be known to the ends of the earth that God rules over Jacob” (Ps 59:13). One psalmist declares that God is “the hope of all the ends of the earth and of the farthest seas” (Ps 65:5) and another prays, “may God continue to bless us; let all the ends of the earth revere him” (Ps 67:7).

But in this psalm, the dominion of God reaches beyond this life, to humans who lie in the realm of those who have died. “To him shall all who sleep in the earth bow down; before him shall bow all who go down to the dust” (v.29). A number of other psalms indicate that “in the dust” is where the dead rest (Ps 7:5; 30:9; 90:3; 104:29; likewise Job 10:9; 17:16; 20:11; 21:23–26; 40:12–13).

In Daniel’s grand vision “at the time of the end” (11:40–12:13) he refers to “many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt” (12:2). This is a key Hebrew Scripture text which is used in discussions of the resurrection as reported in the New Testament. Clearly, those who “sleep in the dust” are dead.

In the archetypal story that opens Hebrew Scripture, “the dust of the ground” is identified as the source for God’s creation of humanity (Gen 2:7)—and as the place where people’s bodies go when they die. The man Adam is told, “you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

God, indeed, “knows how we were made; he remembers that we are dust” (Ps 103:14), and in the end, “all go to one place; all are from the dust, and all turn to dust again” (Eccles 3:20). The Preacher wistfully observes that at the end, “when the years draw near … the silver cord is snapped, and the golden bowl is broken, and the pitcher is broken at the fountain, and the wheel broken at the cistern, and the dust returns to the earth as it was, and the breath returns to God who gave it”, before drawing his inevitable and well-known conclusion, “Vanity of vanities, says the Teacher; all is vanity” (Eccles 12:1, 6–7).

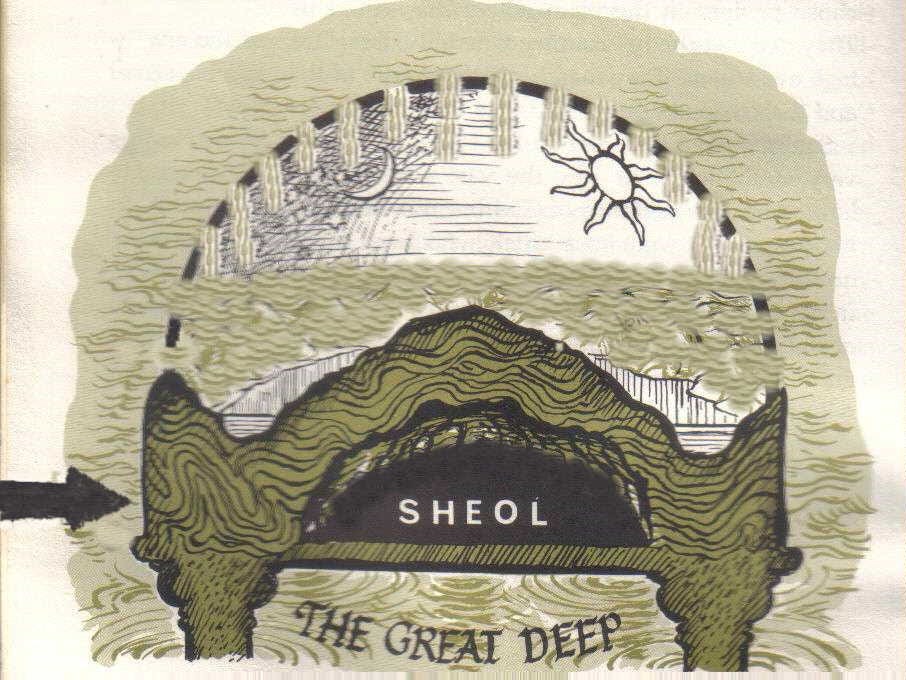

In other passages in the Hebrew Scriptures, those who are dead are located, not in the dust, but in Sheol, in The Pit. These terms each describe the state of the nephesh (the essence of being) of those whose bodies have died. In one psalm, the pit that is dug for “the wicked” describes this place as “the land of silence” (Ps 94:17), while the prophet Ezekiel imagines it as the place where the dead, the “people of long ago” lie “among primeval ruins” (Ezek 26:20).

In Psalm 88, when the psalmist laments “my soul is full of troubles”, they use these and other terms in poetic parallelism to describe their fate: “my life draws near to Sheol; I am counted among those who go down to the Pit; I am like those who have no help, like those forsaken among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom you remember no more, for they are cut off from your hand; you have put me in the depths of the Pit, in the regions dark and deep” (Ps 88:3–6).

In this state, people simply lie in darkness, not living, with no future in view, no hope in store. Job laments, “if I look for Sheol as my house, if I spread my couch in darkness, if I say to the Pit, ‘You are my father,’ and to the worm, ‘My mother,’ or ‘My sister,’ where then is my hope?” (Job 17:13-15). Job also equates entering the Pit with “traversing the River” (Job 33:18), in words that seem to reflect the River Hubur (in Sumerian cosmology) or the River Styx (in Greek cosmology), the place where the souls of the dead cross over into the netherworld.

Other words for Sheol in Hebrew Scripture include Abaddon, meaning ruin (Ps 88:11; Job 28:22; Prov 15:11) and Shakhat, meaning corruption (Isa 38:17; Ezek 28:8). These terms indicate the forlorn, lost, irretrievable nature of this state of being. This is the fate in store for all human beings, whether righteous or wicked; there is no sense of judgement or punishment associated with this state. It is simply a state of non-being.

And yet, even in this state—this state where “my mouth is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue sticks to my jaws; you lay me in the dust of death” (Ps 22:15)—the psalmist finds hope. They are confident that the Lord God “raises up the needy out of distress” (Ps 107:41) and “lifts up the downtrodden” (Ps 147:5). In like manner, Hannah has sung that the Lord “raises the poor from the dust and lifts the needy from the ash heap” (1 Sam 2:8; also Ps 113:7).

And so the psalmist bursts into praise for what, they are confident, God will do. Calling for their listeners to “praise [the Lord] … glorify him … stand in awe of him” (Ps 22:23), they affirm that God “did not despise or abhor the affliction of the afflicted; he did not hide his face from me, but heard when I cried to him” (v.24) and rejoice that “the poor shall eat and be satisfied” (v.26).

The psalmist is certain not only that “the ends of the earth shall remember and turn to the Lord and all the families of the nations shall worship before him” (v.27), but also that “posterity will serve him; future generations will be told about the Lord, and proclaim his deliverance to a people yet unborn, saying that he has done it” (vv.30–31).

And so, they offer this resounding declaration of hope: “to him, indeed, shall all who sleep in the earth bow down; before him shall bow all who go down to the dust” (v.29). It is that hope which we hear, and affirm, when these closing verses of this psalm (vv.23–31) are read or sung during this coming Sunday’s worship.