As the Narrative Lectionary continues to offer passages from Luke’s Gospel, this coming Sunday we will hear two stories from Luke 7: a story of a dying slave (7:1–10) and a story of a grieving widow (7:11–17). As is often the case in this orderly account of the things being fulfilled among us, the two scenes are intended to be complementary and interrelated.

There are two parallels to Luke’s account of the story of the healing of the centurion’s servant. One is in Matthew’s book of origins (Matt 8:5–13), the other in John’s book of signs (John 4:46–54). It’s a story that points to some important Lukan themes.

The figures at the centre of this story are the centurion and his slave (doulos) who was ill, “at the point of death” (7:2); these characters appear also in Matthew’s account, where the ill person is his servant (pais). In John, Jesus engages with “a royal official”, whose son (huios—not servant or slave) was ill. The story is obviously the same, even though the characters are slightly different.

Only Luke reports that Jewish elders were sent by the centurion to Jesus, to function as intermediaries (7:3). There are no such intermediaries in the versions found in Matthew and John. It is been hypothesised that this avoids having Jesus come into direct contact with a Gentile—although, as we have seen, Gentiles were surely already present listening to Jesus and being healed by him (6:17–20). Nevertheless, Jesus himself follows the protocols expected of a faithful Jew, by not entering the house of a Gentile.

This is in accord with the statement placed in the mouth Peter, when he met with Cornelius some years later: “it is unlawful for a Jew to associate with or to visit a Gentile” (Acts 10:28). This position, of course, was overturned by the vision that Peter saw in Joppa (10:11–12), and led to his desire and intention to share in table fellowship with Cornelius (as is implied by 10:23a and 10:48). This is the big, climactic moment in Luke’s two-volume account of “the events that have been fulfilled among us” (Luke 1:1), when the Jew—Gentile barrier is broken down and the fully inclusive nature of the church is revealed.

To have Jesus deliberately adhere to traditional Jewish protocols in his engagement with the centurion in Capernaum allows for the dramatic build-up to this pivotal scene in Acts. We might note also that Luke omits the section of Mark (7:1–20) in which Jesus explicitly “declares all food clean” (7:19), which also points to the climactic intent in the Peter—Cornelius narrative. Leaving out that section of Mark ensures that Luke doesn’t spoil the impact of the later scene in Acts.

A later text, the Mishnah, from the 3rd century, states that “the houses of Gentiles are unclean” (m.Oholeth 18.7). However, it is not clear either that this dictum was in force in the time of Jesus, or that Jesus felt compelled to adhere to it as a sign of his keeping “pure” in terms of the holiness system of the day. Indeed, his later practice—paradoxically—is to share at table with tax collectors or sinful people, which indicates a willingness to breach the strong boundaries of that system. See https://johntsquires.com/2019/05/22/jesus-and-his-followers-at-table-in-lukes-orderly-account/

Only Luke reports that the centurion—a Gentile authority figure—had a relationship with the Jewish synagogue in Capernaum. Indeed, the Jewish elders give accolades to this man, stating that “he loves our people, it is he who built our synagogue for us” (7:5). That reveals an interesting relationship, positive and supportive, between a Gentile (the centurion) and the local Jewish community. So the barrier which Jesus allegedly maintains by not visiting the Gentile house is breached by the patronage (and, we presume, the visits) of a Gentile to a Jewish synagogue.

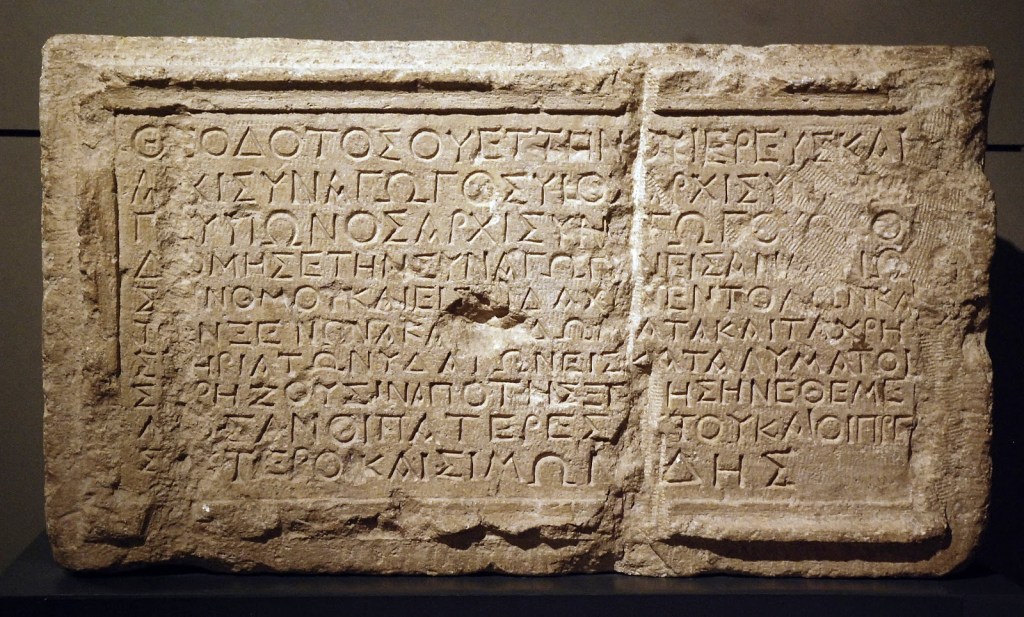

Gentile patronage of Jewish synagogues is known from outside the New Testament; an inscription found in Jerusalem, which is dated from before the fall of the Temple in 70CE, indicates that a certain Theodotus “built the synagogue for the reading of the law and the teaching of the commandments, and also the guest chamber and the upper rooms and the ritual pools of water for accommodating those needing them from abroad, which his fathers, the Elders and Simonides founded.” See https://www.worldhistory.biz/ancient-history/52996-the-theodotus-inscription.html

“Only speak the word”, the elders beg Jesus, “do not trouble yourself” to come all the way to the house (7:6–7). In this way, they maintain the protocols, and try to ensure that that Jesus is kept from defiling himself. This is an interesting positive perspective on the Jewish leadership—a positive assessment that Luke often provides. (See, for instance, how positively he depicts the Pharisees in various scenes: 7:36; 11:37; 13:31; 14:1; and also Acts 5:34; 23:9).

Jesus affirms the man with the words, “not even in Israel have I found such faith” (7:9). This affirmation is given also in the account of this incident in Matthew’s book of origins (Matt 8:10), but not in John’s version of the encounter.

In these words, Jesus sounds a theme which recurs in his subsequent affirmations of the faith of the woman who anointed his feet (Luke 7:50), the woman who had suffered from haemorrhages for twelve years (8:48), the returning Samaritan leper (17:19), and the blind man outside Jericho (18:42), all of whom were characters on the edge, or outside, the central purity group. These affirmations sit uncomfortably alongside Jesus’ recurring lament over the lack of faith of his own followers (8:25; 12:28; 17:5–6; and see also 18:8; 22:31–34).

It’s also noteworthy that the statement of judgement found at Matt 8:11–12, where the characteristic Matthean theme of judgement over the sinful people of Israel is found, is omitted from the Lukan version of the story—although Luke does include this saying in his orderly account at a later point (13:28–30), in the context of his lament over the fate that lies in store for Jerusalem (13:31–35). That different context gives it a narrower focus than the Matthean setting, in which appears to be a (typically Matthean) global condemnation of the people of Israel.

Luke ends this incident with a simple report that the slave was found to be well once again (7:10), as does Matthew (8:13).

The story that follows, recounting how Jesus raises from the dead the son of a widow in the town of Nain (7:11–17), is also a key passage. It narrates the raising of a person from the dead, yet is nowhere near as well-known as the story in John’s book of signs, about Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead (see

I consider that the key point of this story is to establish Jesus as a prophet who enacts the visitation of God for the people of Israel (7:16). It is strange that the NRSV renders this statement as “God has looked favourably”, but it is the same verb (episkopeo) which appears at 19:44, where it is more accurately translated as “the time of your visitation from God”. And in that passage, Jesus comes to pronounce judgement up the sinful city.

It is clear that Jesus, by raising this man from the dead, demonstrates his credentials as a prophet, as the people cry that “a great prophet has risen among us!” (7:16)

The cry of the people also signals that the divine is drawing near to the people of Israel. It is curious that this story sits so deeply within the shadow cast by that other story of raising a man (Lazarus): from the dead. This is a striking and dramatic story, as is attested in the response of the people, of whom Luke reports, “fear seized all of them, and they glorified God” (7:16).

Fear (or better, awe) is the regular response in the presence of an angel (Zechariah, 1:12–13; Mary, 1:30; the shepherds, 2:10). It is also evoked by a miracle, as is seen in the responses of the neighbours of Zechariah and Elizabeth (1:65); Peter, James, and John after the huge catch of fish (5:10); the people of the Gerasene countryside (8:37); a messenger from the house of Jairus (8:50); and Peter, James, and John at the Transfiguration (9:34). Fear is also, understandably, manifest before the divine activity in the days of distress when “the powers of the heavens will be shaken” (21:25–26) when the Son of Man appears in power and great glory (21:27). It’s a climactic end of to a striking story, found only in Luke’s work.