As the year turns from “old” to “new” (at least in our secular calendrical reckoning), we hear familiar words reflecting on the passing of time. For the Preacher, the author of Ecclesiastes (Ecclesiastes 1:1), time is not a linear progression of units, ceaselessly marching forward, relentlessly ageing us, continually moving us on,,driving us to growth, improvement, and “progress”. Rather, time is seen as a sequence of moments, each with their own significance, about which we are invited to pause, reflect, and consider deeply.

The Hebrew Scripture passage that the lectionary proposes for New Year’s Day, 1 January (Eccles 3:1–13), gives a clear indication of how time was regarded in the ancient world. As some people are dying, infants are being born; as some people are weeping, so others celebrate joyously. As some people hunker down in protracted warfare, so others are enjoying a much-yearned-for peace; as some people are happily moving into a new house, a new community, so others are bidding a sad farewell to what has been a beloved home for decades.

At this moment, the continuation of the war in the Ukraine, the perpetuation of bombing in Gaza, the ongoing Sudanese conflict, and the insurgencies in numerous African nations—all of this, and more, continues, while people across the world rejoice at the birth of a new child, celebrate a new marriage, give thanks for a milestone reached in the long life of a much-loved family member. Each and every day, there is “a time to weep, and a time to laugh”.

The Preacher invites us to consider what the season, the time, might be for us at this moment; what might we embrace, and what might we relinquish? How might we best speak into a situation, and when is it wisest to hold our tongue and keep silent? Will this be a year when war continues, or peace grows? Shall we dance—or mourn?

These questions are posed, implicitly, by the rhetorical impact of the repeated “a time to … and a time to …”; for God “has made everything suitable for its time”. What is the time, for us, for me, at this moment, as the year turns?

Pondering what is suitable for this time led me to look also at what the lectionary offers for this same day, 1 January, which is recognised in some parts of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church as the Feast of The Holy Name of Jesus. There is evidence that this feast was celebrated from the 15th century onwards, and it is usually placed on 1 January because this is eight days after Christmas Day, the conclusion of the “octave of Christmas” in Catholic churches.

The feast is based on the simple declaration by Luke: “after eight days had passed, it was time to circumcise the child; and he was called Jesus, the name given by the angel before he was conceived in the womb” (Luke 2:21). This is the concluding verse of the section of Luke’s orderly account which is proposed as the Gospel for this day. The lectionary also suggests that the Epistle reading be Gal 4:4–7.

On this, see https://johntsquires.com/2023/12/28/born-of-a-woman-born-under-the-law-gal-4-christmas-1b/

The Hebrew Scripture suggestion is the short poetic fragment in Num 6:22–27, which ends with the comment, “they [Aaron and his sons] shall put my name on the Israelites, and I will bless them” (Num 6:27), so in a sense it fits for a day which remembers “the name”, even if not that of Jesus. The blessing which the priestly family speaks over the Israelites is well-known: “the Lord bless you and keep you …” (Num 6:24).

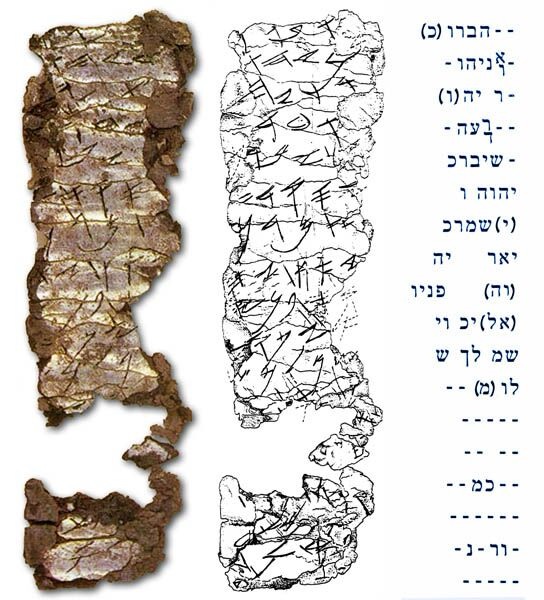

This short poetic blessing lays claim to being an ancient part of scripture—perhaps one of the oldest passages? Indeed, the oldest artefact which contains a text from scripture is a silver scroll, dated to around 600 years before the time of Jesus, just before the Exile began. The scroll has a part of these words of blessing inscribed on them. We moderns have only known about this scroll since 1979, when it was discovered as one of a pair of silver scrolls in a cave in the Old City of Jersualem. See https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/inscriptions/140.html

and for a more detailed analysis,

As the year turns from old to new, it is most fitting that we recall this ancient priestly blessing, to send us on our way in the year that lies ahead.

The words on that tiny tightly-rolled strip of silver were well-known, of course, for centuries before Jesus. They are fragments of the beautiful words of blessing, given by God to Aaron through Moses, for Aaron and his priestly descendants to use as a blessing upon the people of Israel (Num 6:24–26), as well as a fragment from Deut 7:9 in which the importance of keeping the Torah is stated.

The blessing of Num 6 is simple in structure: three parallel clauses, with three verbs that express the same action (bless you / make his face shine on you / lift up his countenance upon you), followed by three further verbs in parallel (keep you / be gracious to you / give you peace). The movement from beraka, blessing, to shalom, peace (or better, wholeness) surely reflects God’s desire and intention towards faithful people of all time.

This blessing, for God’s light to shine, is reflected elsewhere in scripture. The psalmist prays “restore us, O God, let your face shine, that we may be saved (Ps 80:3, 7, 19). “There are many”, says another psalmist, “who say, ‘O that we might see some good! Let the light of your face shine on us, O Lord!’” (Ps 4:6). In Psalm 31, another psalmist sings, “Let your face shine upon your servant; save me in your steadfast love” (Ps 31:16).

In the seventeenth section of the longest of all psalms, Psalm 119, a prayer asking for God to help the psalmist keep the Law culminates with the request for God’s face to shine: “Turn to me and be gracious to me, as is your custom toward those who love your name. Keep my steps steady according to your promise, and never let iniquity have dominion over me. Redeem me from human oppression, that I may keep your precepts. Make your face shine upon your servant, and teach me your statutes.” (Ps 119:132–135).

The author of Psalm 67 echoes more explicitly the Aaronic Blessing, praying, “May God be gracious to us and bless us and make his face to shine upon us—Selah—that your way may be known upon earth, your saving power among all nations” (Ps 67:1–3). This reflects the wording and pattern of the ancient priestly blessing recorded in Num 6:24–26: “The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you; the Lord lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace.”

In this three-line prayer, the second line includes the phrase, “the Lord make his face to shine upon you”. The simple parallelism in this blessing indicates that for God to “make his face shine” (v.25) is equivalent to blessing (v.24) and lifting up his countenance (v.26). The second verb in each phrase is, likewise, in parallel: the psalmist asks God to keep (v.24), be gracious (v.25), and grant peace (v.26).

These words offer a prayer seeking God’s gracious presence for the people of Israel. They are also words which we might well hear, and appropriate, for our lives of faith in the year stretching ahead of us. May there be keeping, grace, and peace, in our lives, and in the lives of others around us and far from us.

which contains part of the text of the Priestly Blessing:

a photograph, a transcription, and the fragmentary text in Hebrew script