This essay and the one which follows it in a subsequent blog is written by my friend and colleague, the Rev. Dr Geoff Dornan, offering a Christian ethical perspective on a recent controversy (one of so, so many) in the United States of America. Geoff has a PhD in Philosophy, Theology & Ethics from Boston University, USA. He is currently serving as Minister in Placement at Wesley Uniting Church in Canberra, ACT.

1. INTRODUCTION: JD VANCE ON ORDO AMORIS

In an interview by Fox News’ Sean Hannity, on January 30th this year, the U.S. Vice President. J.D. Vance offered a theological and moral defence of the Trump Administration’s policy of forced mass deportations.

This policy revokes the temporary legal status of potentially hundreds of thousands of people without due process, in defiance of the fifth and fourteenth amendments of the American constitution.

In the discussion, Vance declared that “the far left” in the United States tend to have “more compassion” for people residing in the country “illegally” (my apostrophes), including those who have committed crimes, than they do for American citizens. He opined that compassion should first be directed to fellow citizens, adding that this does not mean that people from outside of one’s borders, should be hated, but that one’s priority should be for those within.

In support of his contention, Vance said:

“But there’s this old-school [concept] – and I think a very Christian concept, by the way – that you love your family, and then you love your neighbour, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country, and then after that you can focus and prioritize the rest of the world.”

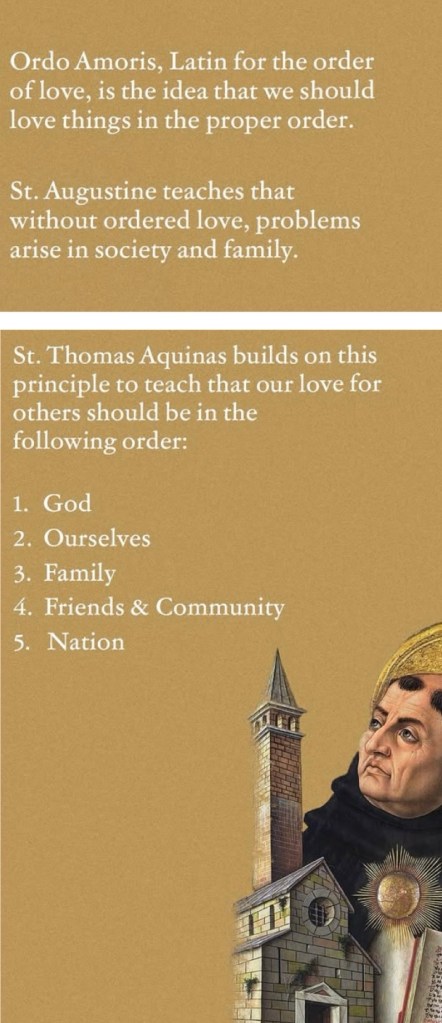

The idea to which Vance referred was that of St Thomas Aquinas, commentated upon in his great body of work, the Summa Theologica, known as ordo amoris – “rightly ordered love”.

Later that evening Vance responded on social media to a British professor and former conservative politician, Rory Stewart, who criticized Vance’s comments as a “bizarre take on John 15:12–13” and as “less Christian and more pagan tribal.” (The Bible verse referenced by Stewart reads “This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you.”).

Stewart’s reference to this verse, and its relevance to the point he was labouring to make, was not and is not altogether clear. Perhaps because of that fact, he then referred to the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37), applying the story as a legitimation of foreign aid.

Vance curtly responded to Stewart’s confusing comments with, “just google ordo amoris”!

The reaction that has flowed from these two interviews has been discordant. On the one hand, there has been some approval, a positive nodding of the heads from some theological and political circles.

On the other there has been clear disapproval from the Catholic leadership. Some responses have on the other hand fallen in between, seeking to qualify Vance’s response.

Regarding the first, the theological publication First Things included an article entitled “JD Vance States the Obvious about Ordo Amoris” by James Orr, Associate Professor of Religion at Cambridge, and notably, UK Chair of the conservative Edmund Burke Foundation. Orr argued that Stewart’s appropriation of the Good Samaritan was mistaken, in as much as its message is not that one should help all victims wherever they may be, but that we must care for those who fall within the compass of our practical concern.

In keeping with this take, he points out the Greek word for neighbour in the New Testament is πλησίον (plēsion), which is derived directly from πλησίος (plēsios), meaning “near” or “close by.” Apparently then, according to Orr, it is proximity that makes neighbours our objects of care and attention.

In contrast to Orr, the Catholic leadership has shown notable dissatisfaction with Vance’s interpretation. Pope Francis, attributing Vance’s motivation and appropriation of Ordo Amoris to the Trump Administration’s defensive armoury for deportation of non-citizens without due process, said to the US bishops on February 10th that “an authentic rule of law is verified precisely in the dignified treatment that all people deserve, especially the poorest and most marginalized”. He averred that such policy and practice “does not impede the development of a policy that regulates orderly and legal migration”.

In other words, good policy can and must include dignity for such people. Targeting Vance’s take on Aquinas within the context of Christian social ethics, he continued that “Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups. He proffered, “the human person is not just a mere individual, relatively expansive, with some philanthropic feelings”. As if to ensure the point could not be missed, he added, that the “true ordo amoris that must be promoted is that which we discover by meditating constantly on the parable of the ‘Good Samaritan’… that is, by meditating on the love that builds fraternity open to all without exception”.

Pressing the point further, it is widely understood that Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican Secretary of State and confidant of Francis, was later tasked with speaking to Vance to ensure that there could be no ambiguity or misunderstanding as to the Holy Pontiff’s point. Moreover, Cardinal Robert Prevost, prior to his recent election as pope, posted a tweet on February 13th, sharing several links to articles critical of Vance’s take on Ordo Amoris. Prevost, now Pope Leo XIV, has had a long history of working among the poor in northern Peru, passionately supporting the rights of those who seek lives of dignity.

2. THINKING THROUGH THE CATHOLIC TRADITION

So, what to make of this?

On the one hand, the US administration lays hold of the writings of Thomas Aquinas, Doctor of the Catholic Church (referred to hereafter simply as Thomas, in keeping with Catholic academic tradition).

The US Administration took hold of the words of Thomas for its own purposes, seeking to legitimise its policy and practices regarding immigrants deemed illegals, while the Catholic leadership expresses its annoyance at what it considers the abuse of Church teaching, pressed intoservice in an attack upon the vulnerable.

In the following paragraphs, I shall examine two things: first, Thomas’ theology: setting it in context, explaining its strengths and limitations. Second, I shall set out the developments in Catholic instruction since Thomas: the movement from neo-Thomism to modern Catholic theology, and particularly the Social Teachings of the Catholic Church, of which Vance seems unaware, despite their more recent genesis in Western theological and moral discussion.

A. THE WORLD VIEW OF THOMAS AQUINAS, 1225–1274: SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ETHICS AS A ‘RIGHT ORDERING’

from Ascoli Piceno in Italy, by Carlo Crivelli (15th century)

Thomas Aquinas’ world view unsurprisingly reflects the mediaeval age in which he lived but builds upon it in unique ways. His thinking was one of the greatest attempts of Mediaeval Scholasticism after the fall of the Roman Empire to unite in one body knowledge and revelation, philosophy and theology.

For Thomas, the human being is by nature a social animal. In speaking in this way, hedraws from the inspiration of Aristotle, most of whose writings had only been rediscovered by the western church a little earlier, between 1150 and 1250, stimulating an explosion of intellectual energy. Additional to Thomas’ appreciation of the social nature of the human being, he holds a view of society as firmly ordered and hierarchical; and this, according to his understanding of the Divine plan. The whole structure of things reflects what Thomas considered the natural order of humanity as created by God.

Ernst Troeltsch, an early sociologist of religion, in his classic Social Teaching of the Christian Churches (1911), interpreted Thomas’ way of seeing things – what we call the ‘Thomist ethic’ – as the ultimate expression of an “ecclesiastical unity of civilization”. Thomas’ ethic touched every element of mediaeval life, framed by its division between nature and supernature. It furnished a theoretical justification for social hierarchy, insisting upon an ethical purpose for each social role and place.

In essence, the church with its treasury of merit and sacraments, provided the means of grace through which the temporal life gained eternal meaning. From a sociological point of view, as J. Philip Wogaman puts it, “the system made it possible for there to be a unity of civilization (my italics), encompassing not only ‘ordinary’ Christians whose faith was inevitably corrupted by the world, but also those who sought the purer morality and spirituality of monastic life.”

But was this social ethic, this hierarchy of living, a strict top-down affair, that ‘softly’legitimized injustice? On this question, opinion is split. Some subscribe to the view that Thomas’ ethic was a distinct advance upon hitherto mediaeval arrangements.

To the extent that all aspects of society served specified ends – the highest ranks serving those beneath them, and the lowest serving their superiors – a basic form of mutuality was envisaged, grounded in the common good. Such an arrangement it is argued, relieved the mediaeval system of its worst features.

Others, however, subscribe to the opposite view: that Thomas does little more than defend the pattern of living of thirteenth century Europe, holding that pattern as proper for all societies and times. Both sides are probably correct. Thomas was no social radical, although he was a man of great intellectual acumen, as he created a synthesis of thought of the pagan philosopher Aristotle and the early Church Father, Augustine.

Turning to Thomas’ political ethic, Thomas sees the state or political community as a “perfect” society, in the sense that it has all the means necessary to fulfil its appointed purpose of the common good, by which he means material development and the pursuit of virtue. It must be added that this includes coercive force to restrain vice and evil, to ensure the peace of the whole.

But let us be clear about the power of state coercion! For Thomas is no simple authoritarian.

He pragmatically understands that not all vices can be expungedwithout at times generating more problems. As such, he holds that the state must never attempt to do what cannot be done effectively.

So, overall, both Thomas’ social and political ethics are grounded in a special ordering;certainly conservative when contrasted with western modernity, nevertheless, moderate in that Thomas sees that the state has its limits.

B. ORDO AMORIS: THE RIGHT ORDERING OF LOVE?

On the one hand, the US administration lays hold of the writing of Thomas Aquinas, Doctor of the Catholic Church, for its own purposes, seeking to legitimise its policy and practices regarding immigrants deemed illegals, while the Catholic leadership expresses its annoyance at what it considers the abuse of Church teaching, pressed intoservice in an attack upon the vulnerable.

In the following paragraphs, I shall examine two things: first, Thomas’ theology: setting it in context, explaining its strengths and limitations. Second, I shall set out the developments in Catholic instruction since Thomas: the movement from neo-Thomism to modern Catholic theology, and particularly the Social Teachings of the Catholic Church, of which Vance seems unaware, despite their more recent genesis in Western theological and moral discussion.

And so, to Ordo Amoris, the right ordering of love within Thomas’ social and political ethics! The problem as I see it, is that his attempt to affirm this principle has its difficulties. In large part, this is so, because of his approach in assuming a hierarchy of obligation. Let us explore this.

For Thomas, love of and for God stands above all else in the hierarchy of love. From there in Ordo Amoris, Thomas orders or grades all other loves based on the just claims that a person may make upon another’s love for them. Here lies the seed for the idea that we owe a debt of love to those in closest proximity to us, for they are entitled to such an expectation.

For Thomas, to neglect those nearest to us, on the pretext of loving more broadly and generously those who are afar, is not to really exercise love at all. As V.J. Tarantino explains through the story of Lazarus in the Gospel of Luke, “To skip over Lazarus on the doorstep [in order] to volunteer at the charity auction, is at least to some degree a matter of self-satisfaction”, [rather than love]”.

But what is the difficulty here? Let us name it! The point is that Thomas’ undertaking to establish theoretical rules for whom we are to prioritize in love, is tricky. Yes, Thomas does indeed maintain that a man should love his fellow citizens before the stranger; his father before his mother; both parents before his wife and children; and, before all non-family outsiders, his civic ruler.

However, this rule-bound way of operating appears to be deficient: first as mentioned earlier, because love is explained in terms of what is owed, but second because his thought is so mechanistic, so duty driven, ignoring the very nature of human love, which is altogether a more spontaneous, impromptu, Spirit led thing.

Joseph Ratzinger, better known as Pope Benedict XVI (2005–2013) in his stand-out encyclical Deus Caritas Est (God is Love) makes exactly this point: that love is not about duty bound commandments, imposed from outside of the human person, but rather a freely bestowed experience beginning with God, which by its very character drives us to share itintuitively with others.

Pope Francis (2013–2025) says something similar by way of application of Benedict’s insight. In his encyclical Fratelli Tutti (On Fraternity and Social Friendship), as he writes about the story of the Good Samaritan, he emphasizes that the priest and the Levite were most concerned with their duties as religious professionals.

Their structured social roles and their structured ethics, which determined who would enjoy a higher place as beneficiaries of their love, blinded them to the distraction of the man on the roadside, who simply did not fit. Love, as they understood it, was a duty owed to specific groups, not something to be freely, graciously, injudiciously lived out.

3. THOMAS: A TRIAL BALANCE

What then may we conclude about Thomas’ approach to the ethics of love? While love of and for God remains the genesis of everything, nevertheless the ordering of love which follows from it, is bound to and limited by the social and political structures of which Thomas was a part.

On the other hand, there is no sense in Thomas that love is simply a limited quantity that is to be parcelled out to those close to us, with little or nothing left for those in need; that there is only so much that can go around. He does understand order – after all he was a systematic theologian and carries his systematization into everything he writes – but to assume, as Vance does, that he would give his blessing to mass deportation, and this without legal due process, goes too far.

So, is there anything missing in Thomas? I think there is: the extraordinary liberality, largesse, the remarkable prodigality of the Gospel. In the broad scheme of things, Thomas does not manage to reflect the richness of the Good News. Tarantino puts it so well: “the erring sheep…preferred to the ninety-nine obedient sheep; the worker who commences at the final hour…compensated in equal measure to the one who laboured from daybreak; the tax collectors and the prostitutes…entering Heaven; the last [being] first; and God himself [giving] his only Son”.

4. BACK TO J.D. VANCE AND HIS APPROPRIATION OF THOMAS

In this paper I have sought to answer the question whether the American Vice President J.D. Vance is justified in harnessing Thomas’ ordo amoris for his political purposes: namely forced mass deportations of people without due process from U.S. territory.

My conclusion is that Thomas does not deliver such justification, but nor is Ordo Amoris adequate in and of itself to provide a definitive answer one way or the other for modern Christian ethics. Rather, to answer the question, one needs to turn to more recent moral theology of the Catholic tradition. I refer to Catholic Social Teachings, which I shall examine in the next essay.