A sermon on Proverbs 8: 22–36, preached by the Rev. Elizabeth Raine in St Stephen’s Uniting Church, Sydney, at a service of Closure of Ministry for the Rev. Jane Fry, outgoing Secretary of the Synod of NSW.ACT, on Wednesday 29 October 2025.

When Jane asked me to preach at this event, I was very surprised. I expected that a former Moderator or Board Chair would be invited to preach at such an important event as the General Secretary of the NSW/ACT Synod retiring. But here I am!

It is true that Jane and I go back many years, as we went through UTC together, bonded by the attitude of the sexist male colleagues who accused us from everything from ‘sleeping our way to high distinctions’ to being ‘feminists’, like it was some sort of virus. I confess this rather patriarchal attitude has informed this sermon, though it is also true that so many more women now occupy prominent positions in our church, which is a very good thing.

I did warn her that I was unsettling, potentially feral and capable of saying things that were unfiltered in my sermons. Was she sure she wanted to risk such a this? Apparently she did, so here I am.

I was grateful to Jane for her friendship and support then, and I am grateful to her now for her presence as General Secretary over the last 9 years. She has approached this position as she does most things, with integrity, thoughtfulness and a straightforward approach to dealing with what I call ‘faffing around’. Jane has a deep and abiding love for the church and hopes only for its successful transition into the future, and I wish her well for her future in retirement.

The book of Proverbs from which one of the readings we heard is drawn tells us a lot about Wisdom (hochma in Hebrew). She is a central character in chapters 1–9, and she appears as a mystical feminine aspect of God. “Lady Wisdom”, as she is known, is a central character in many chapters of Proverbs, and those who know her are seen asrighteous people. She calls to us and invites us on an unexpected journey. She is offered as a role model for us, her teachings are a template for life, and she a pioneer who opens up a pathway to faith and obedience.

Scholars have debated how the personification of Wisdom should be interpreted, especially as Wisdom is stated to be the first creation of God (“the Lord created me at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts of long ago”, Prov 8:22) and is involved in the creation process itself (“the Lord by wisdom founded the earth”, Prov 3:19). Is wisdom meant to be a specific aspect of God or even a separate being from God? Or should all such language be taken as mere metaphor?

She has been described in many ways—as an aspect of God, as a divine entity existing in her own right, even as something approaching a feminine deity, as Proverbs 8 states: Wisdom was present at the beginning of creation as a co-creator with God, who delighted in her presence.

The divine Wisdom has fascinated ecclesiasts and scholars since the inception of the Christian church. As we have heard, Wisdom has been described in many and various ways but Wisdom’s primary function was understood by the very early Christians to be a mediating force between God and the world, and was particularly associated with the work of creation.

The text from Proverbs 8:22 was important for this belief: here, Wisdom declares, “The Lord created me at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts of old”. Wisdom was believed to be a vehicle of God’s self-revelation, granting knowledge of God to those who pursue her through scripture and learning.

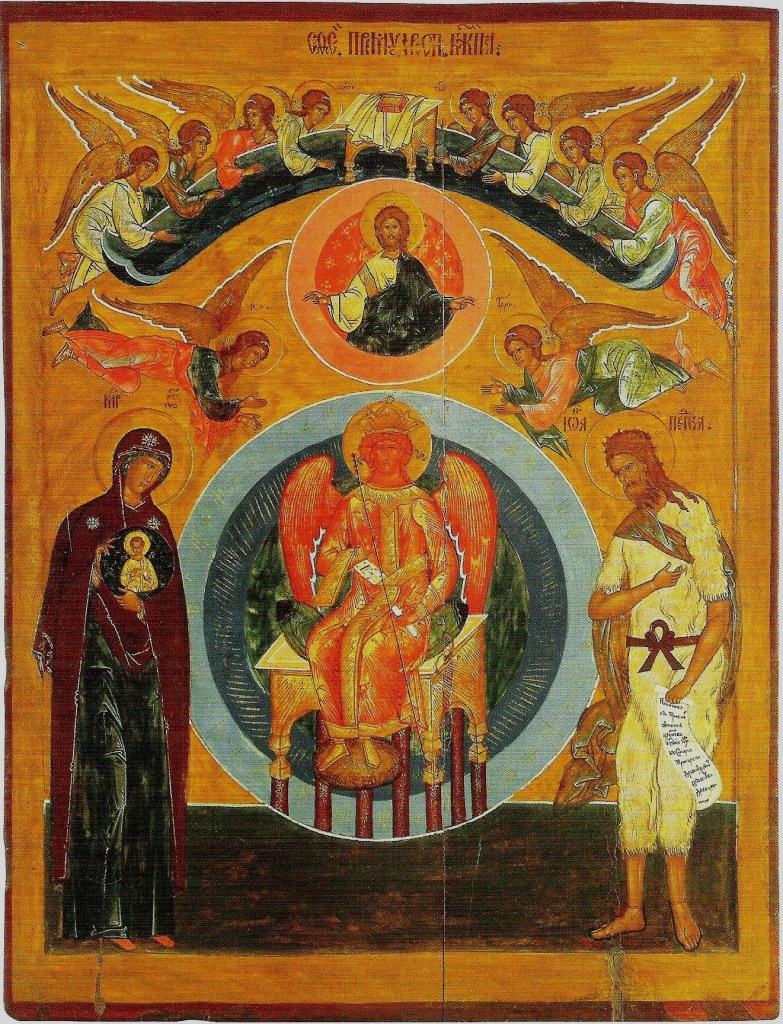

Wisdom (Sophia) on her throne supported by seven pillars

A 16th century Icon of Divine Wisdom

in the St George Church in Vologda, Russia

Despite this, the Christian tradition, for most of its life, cannot be said to be famous for finding the feminine aspect of the divine. Relentlessly masculine, the early Christian church systematically excised any sense of the feminine from the orthodox view of God, spirit and Jesus.

The ruach (Holy Spirit) became masculine through the language of Latin; the bat qol (the voice of God) of the rabbinic literature found a different, masculine grammatical construct in Greek, and hochma or sophia (wisdom) morphed into the figure of Jesus, as the New Testament writings firmly associated the attributes of Wisdom with the person of Jesus Christ.

This last is most clearly seen in the letter to the Colossians. This document was originally attributed to the apostle Paul, but is now thought to have been written by a follower of Paul, soon after the apostle’s death in the early 60s. Some early verses in Colossians make it clear that Wisdom had been grafted onto Jesus:

“He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers — all things have been created through him and for him.”

The Divine Feminine through whom God created the world was replaced with the Divine Masculine. A good example of this can be found in the writings of Justin Martyr – he claimed that Jesus was Wisdom, Logos and the Glory, thereby removing the feminine Spirit (ruach), Wisdom (hochma), and Glory (shekinah) all in one stroke.

Wisdom sadly morphed into a male saviour, who by assuming the divine characteristics Wisdom was meant to share with God, found himself inserted as the third person of a doctrine of trinity with a transgendered holy spirit, who crossed masculine, neuter and feminine across biblical languages.

Instead of recognizing Wisdom, this feminine aspect of the divine, early Christian male leaders instead have tried to satisfy women throughout the world by presenting them with role models of martyrs and virgins, thereby setting a standard that the vast majority of females cannot possibly aspire to.

Wisdom fast lost her independence and feisty nature, and the meek, obedient woman, characterized by the mother of Jesus (another virgin), was held up as the model to which all women should strive to be.

However: far from being obedient and submissive, Wisdom occupies what is the domain of men, teachers and prophets. She stands on busy street corners, she is at the town gate; she sets her table at the crossroads where many pass by. Unlike her counterpart in Proverbs 31, there is nothing of the domestic goddess about her. She is radical, counter cultural and subversive. She teaches knowledge and leads her people on their way through history. In a most unfeminine way, unaccompanied by a male chaperone, she raises her voice in public places that are the domain of men and calls to everyone who would hear her.

Wisdom offers us a radical example of faithfulness yet she remains a disturbing presence. She is a most unladylike figure, venturing outside the house, to stand beside the crossroads, crying out in full voice, surprising and startling and provoking with her words.

She transgresses boundaries by standing amidst the male elders at the city gates and presuming to teach them. She has a clear voice, a colourful personality, a dominant presence, and offers words of hope and the promise of life. She is a vehicle of God’s self-revelation, and grants knowledge of God to those who pursue her through scripture and learning.

The prominent biblical scholar, Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, has written this about Wisdom:

Divine Wisdom is a cosmic figure delighting in the dance of creation, a “master” crafts wo/man and teacher of justice. She is a leader of Her people and accompanies them on their way through history. Very unladylike, she raises her voice in public places and calls everyone who would hear her. She transgresses boundaries, celebrates life, and nourishes those who will become her friends. Her cosmic house is without wallsand her table is set for all.

In short, the biblical figure of Wisdom represents a spirituality of roads and journeys, of public places and open borders, of nourishment and celebration, of justice and equality – rather than a spirituality of categories, doctrines, closed systems and ideologies. Her dramatic modus operandi stands in striking contrast to the slow and methodical way of operating that we see in the classic formulations of Christendom, doctrines that have come to define the church in the eyes of those outside of it.

The church fathers, the male patriarchs of the church, and the myriad of male theologians who followed were, in my humble opinion, consumed with their categories; they articulated their doctrines by amassing the data, analysing the information, systematising the component parts and categorising the key dogmas. And they wrote down these dogmas and systems and turned them into the doctrines by which faith was measured.

By contrast to these closed systems of belief and knowledge, the biblical figure of Wisdom asks for a relational faith, and invites us to develop a wide openness in the way we approach others and God. She requires of us that we really listen to others, including those we don’t agree with … she calls us to listen, to understand, to speak in ways that connect with others and ways that build productive and fruitful relationships across the differences that separate us.

Wisdom calls us to work together, for the common good, with others in our society. She is not a figure bound to buildings, books and writing; she is an outdoor, community spirit, seeking relationships with people, engaging wholeheartedly in the public discourse, debating back and forth in the public arena the key elements of a faith-filled life.

What Wisdom presents is a radical democratic concept, in that anyone, whether illiterate or educated, whether without or with status, whether poor or wealthy, can acquire what she offers.

She invites us to be life-long learners of the faithful and missional type, and calls us to be constantly open to challenge and change as we read, study, think, discuss, explore, debate, and decide.

I think that Wisdom is precisely the kind of person who would have relished the invitation, once offered to his disciples by Jesus, to fish on the other side of the boat. She would value the opportunity to look in a different direction, to reconsider the task at hand and seek a new way of undertaking it. Rather then remonstrating with Jesus saying ’but we have always done it this way’, she would jump at the chance to set out in a new arena, to pioneer a new task, to reshape her missional engagement so that it was fresh, invigorating, and creative, open to new possibilities and exciting pathways. What a role model that is, for the church today!

https://womenspiritualpoetry.blogspot.com/2013/12/lady-wisdom-by-kiernan-antares.html

So, the question that I invite you to ponder at this moment is: How will we interact with Wisdom? Are we open to the exploration and discoveries that the biblical figure of Wisdom invites us to pursue?

Are we content with just repeating our tried and true traditions from the past? Are we happy staying in our familiar comfort zones? Will our mission be simply no more than wishing people to walk through ourdoors, as we remain in our comfortable, self-contained spaces?

Or will we choose the way of the rather unladylike and subversive Wisdom, the radical at the street corner, crying out to all who pass by? Can we adopt Wisdom’s model invitation of radical hospitality as relevant to the church today? Should we be more concerned with ‘raising our voices’ in the public arena than confining ourselves to church buildings?

Hopefully as a church we will choose to follow the path of Wisdom into the future, which through its relational, radical and inclusive theology offers us the potential to transform contemporary situations of injustice, brokenness and violence in the communities we serve. By taking our stance in the marketplace, we can demonstrate the ways that show our deep and profound relationship with and love for God, and how that love is extended to all people. Hopefully all of us, not just a few, can follow Wisdom out of our enclosed gatherings to the space where such social and spiritual change can take place.

I trust that as a church, we will continue to encounter Wisdom, hochma, and learn from her, again and again in the coming years.

*****

You can read a report of the whole service of Closure of Ministry at