A sermon preached by the Rev. Elizabeth Raine at Tuggeranong Uniting Church on Sunday 7 November 2021

*****

We rejoin Ruth and Naomi in chapter 3, where Naomi takes the initiative to securethe future for herself and Ruth, a future that centres around Boaz as a potential husband for Ruth. Naomi issues detailed instructions to Ruth in regard to staging an encounter with Boaz at the threshing floor, a place with a poor reputation in Hebrew scritpure, where Boaz is working late.

Ruth is instructed to bathe, put onher best clothes, and apply perfume, all which signifies romantic intent. Despite the risk, Ruth dutifully obeys, informing Boaz when she accosts him on the threshing floor that she is “Ruth, your servant; spread your cloak over your servant, for you are next-of-kin.” ‘Spread your cloak’ is a Hebrew euhphenism for sexual intercourse, and Ruth is not only signifying her availability for marriage but her desire that Boaz carry out his duty as next of kin according to the Levirite law.

This law required the next of kin of a deceased husband to father a child for the deadman so that his lineage could continue. Boaz takes the hint, and tells Ruth that though there is a nearer next of kin, he will sort this out tomorrow with that closer family member.

In chapter 2 we noted a number of contrasts: male and female, foreigner and Israelite rich and poor, etc. In this chapter we also find contrasts. Boaz and Ruth had met during the day, in a public place, where the social custom for such encounters were maintained. Here they meet in private under the cover of darkness, and unrestrained by custom, their interaction is quite different. We are now in the private domain of women, signified by the night. Boaz’s prominence, riches and public profile are not as important here. It is both a time of danger and a time of potential promise and blessing.

Despite Ruth’s bold initiative, she and Naomi still live in a world that does not value its widowed women, and their fate rests in the hands of a man with wealth and status. Boaz needs now to fulfill his part of the plan in the public, male sphere of lifein chapter 4.

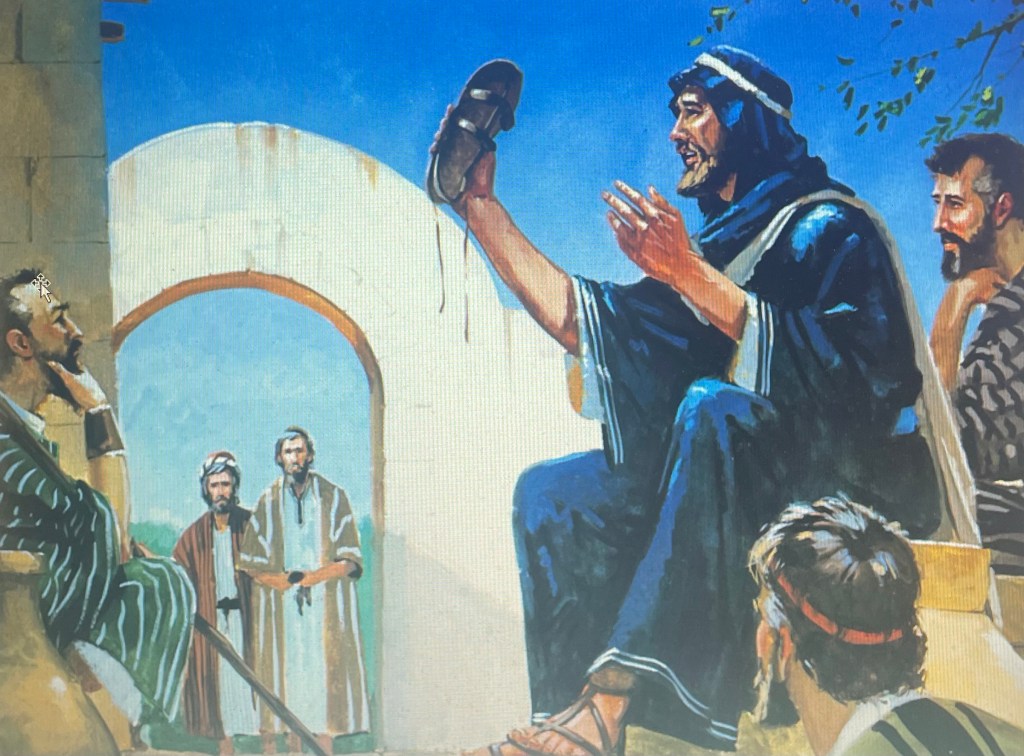

We now return to daylight and the male) domain. The focus shifts from Ruth to Boaz, and from the private to public sphere. Boaz is here to wait for the nearer next of kin, or goel. It is Boaz’s interests that dictate how the exchange between the two men will go, and we can tell this because the Hebrew passage here begins and ends with Boaz’s name. Further, despite the bible translation of ‘friend’, the other goel is called peloni almoni, Hebrew rhyming slang that basically means “old what’s his name”, or “Mr such and such”. Again we see the sense of humour of the author of this book at work.

Boaz is shown to have authority in this society as “Mr what’s his name” and the ten elders do what he tells them to. None of the men he addresses challenges his authority or his right to order them around.

In the ancient Hebrew world, decisions about law, property and finances were made at the town gates, where the men and elders would gather to discuss aspects of law and to enact judgment.

Boaz constructs an elaborate legal argument around an alleged piece of land we haven’t heard of before that Naomi apparently wants to sell. Her nearest kinsman has first right of refusal under Hebrew law. This begs the question: why did Naomi need Ruth to glean if she had land to redeem? Is Boaz resorting to an imaginery piece of land to cover his real aim – which is to acquire Ruth as a wife? It would certainly give him the legal cover he needs for such a proceeding – for even in this rather enlightened book, for someone of Boaz’s social standing to enter into marriage with a Moabite, a foreigner, would be risky if no legal duty is involved.

So while Boaz is apparently concerned with the noble duty of redeeming his kinswoman Naomi’s land, he can just slip in that Ruth is part of the deal as well. Mr “what’s his name” decide that the risk of redeeming the alleged land is too great to him, as if Ruth were to have a child that child could legally claim the land in the future, even if he had paid for it now. So he refuses, and Boaz is free to marry Ruth.

The outcome of this chapter presents a very different family picture from that in the first chapter. Life has replaced death, abundance has replaced famine, fullness of life and fertility has replaced emptiness and barrenness. Amidst the rejoicing of the community, God finally appears as an active character, causing Ruth to conceive a son to Boaz.

Despite this intervention of God, the story is not about divine manipulation or a system where God directly rewards and punishes. The important thing in this story is the role of human action and intervention. God’s grace is bestowed only when such action is taken by the people concerned, and when it concerns all people.

Ruth’s story ultimately has a happy ending because the community decide to accept and welcome her despite being a foreigner.

The book of Ruth challenges us to look more closely at our own cultural context, and how the poor and the foreigner are welcomed and provided for in our community. Even in a world where prosperity has become available for some on a ridiculous scale, many still die of starvation. Many flee countries where food supplies are insufficient, and where opression is rife.

It is clear that true community in our world is broken. Gleaning has been replaced by our welfare system, which is often inadequate to address the real issues facing the poor. If nothing else, the story of Ruth here should challenge us to work for cultural change, to transform the brokeness into a society where all are equally valued.

The little genealogy at the end probably strikes the modern reader as a rather oddaddition, but it has a special function. If further proof is needed by the reader of Ruth that God favours the inclusion of the foreigner, this is it. The gift of children was regarded as a sure sign that God’s blessing was resting upon a person. Ruth is the great grandmother of King David, the most famous of Israel’s kings in the biblical record. The genealogy shows that by accepting the foreigner, Israel goes on to beextraordinarily blessed.

Many generations later, some people in Israel became followers of the one whom they believed had been chosen by God to be the Messiah. They claimed that this man from Nazareth was a descendant of the great King David; this claim would be crucial to establishing his credentials amongst his Jewish contemporaries. And since the man from Nazareth was descended from David, he was also descended from Ruth, the Moabite and foreigner. Without this story of the refugee and the foreigner, who married across ethnic boundaries and became part of a new family, there would be no David – and thus, no Jesus.

From the simple act of welcoming and giving hospitality to the stranger and foreigner, and building a new life with new relationships and new hopes, new outcomes and consequences can happen that were never imagined at the outset.

Lead us, O God,

in the way of Christ, the servant,

who opened his arms to the poor and the foreigner.

Lead us, O God, in the way of welcoming the stranger

caring for the neglected, feeding the hungry,

housing the homeless, and challenging the powerful,

Lead us, O God,

in the foolish way of the Gospel,

which turns the world upside down to bring salvation to all.

Amen.