“Save us, we beseech you, O Lord!” This is the cry we hear in the psalm which is offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday, Palm Sunday, the Sunday in Lent. Psalm 118 is one of the Hallel Psalms—six psalms (113 to 118) which are sung or recited on high festival days, such as Passover (Pesach), the Festival of Weeks (Shavuot), and the Festival of Booths (Sukkot), as well as Hanukkah and the beginning of each new month. This final Hallel Psalm, like the other five, is intended to be an uplifting, celebratory song, suitable for the congregation to hear and to sing as a way to inspire and rejoice.

See

It is no surprise that this psalm is offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday, Palm Sunday—because the Gospel story for this day, of Jesus entering the city of Jerusalem to the acclaim of the crowd (Matt 21:1–11), is certainly one of celebration and joy. It is also, equally unsurprisingly, offered as the psalm for a week later, on Easter Sunday, which celebrates something much greater and more enduring: the raising of Jesus from the dead (Matt 28:1–10).

But clearly the psalm has a good fit with the Palm Sunday story that we will hear on Sunday; indeed, the Gospel writers report that the crowd cheering Jesus was singing, “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord”—which is, of course, a verse from the final Hallel Psalm (Ps 118:26).

Blessing God is a favourite Jewish activity—indeed, so many prayers still used by Jews today begin with a phrase of blessing: “Blessed are you, O Lord our God …”. Blessed are You, O Lord our God, Ruler of the universe, Who brings forth bread from the earth is prayed before a meal. Blessed are You, O Lord our God, Ruler of the universe, who creates the fruit of the vine is prayed before drinking wine. And a favourite blessing which I learnt from Jews is Blessed are you, O Lord our God, Ruler of the Universe, who has kept us alive, sustained us, and brought us to this moment. It’s a prayer to mark momentous occasions in life.

All of these prayers of blessing begin with the Hebrew words, Baruch atah Adonai Elohenu melekh ha’olam, the same formula of approaching, acknowledging, and blessing God.

We can see that formula used in blessings spoken by David (1 Chron 29:19 and the psalmist (Ps 119:12), as well as in later Jewish texts such as Tobit 3:11; 8:5, 15–17; Judith 13:17; 14:7; the Prayer of Azariah (six times), and 1 Maccabees 4:20. It appears also in New Testament texts such as Luke 1:68; Rom 9:5; 2 Cor 1:3; Eph 1:3; and 1 Pet 1:3.

More familiar, perhaps, is when Jesus uses a prayer of blessing, but speaks it to human beings; “blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah” (Matt 16:17), or “blessed are the eyes that see what you see”, to his disciples (Luke 10:23), or “blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe” (John 20:29), and most famously of all, in a set of blessings spoken to a crowd on a level place (Luke 6:20–22) or to his disciples on a mountain top (Matt 5:3–12).

So the cry of the crowd as Jesus enters Jerusalem, “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord” (Ps 118:26) is a typical Jewish exclamation at a moment of joyful celebration.

*****

A further reason for linking this psalm with the Gospel narrative might well be that the cry of the crowd, “Hosanna!” (Mark 11:9–10; Matt 21:9; John 12:13). The word transliterated as “Hosanna” might actually be better translated as “save us”—another quote from the previous verse in that same psalm (Ps 118:25). The Hebrew comprises two words: hosha, which is from the verb “to save”, and then the word na, meaning “us”. Hosanna is not, in the first instance, a cry of celebration; rather, it is a cry of help, reaching out to God, pleading for assistance—and yet with the underlying confidence that God will, indeed, save, for “his steadfast love endures forever” (vv.1, 29).

See

Whilst the psalm, overall, sounds thanks for a victory that has been achieved, the petition, “save us” (v. 25) lies behind the first substantial section of this psalm (vv.5–14), which is largely omitted by the lectionary offering for this coming Sunday (which is Ps 118:1–2, 14–24). That section begins “out of my distress I called on the Lord” (v.5), claims that “the Lord is on my side to help me” (v.7), and concludes with rejoicing, “I was pushed hard, so that I was falling, but the Lord helped me; the Lord is my strength and my might; he has become my salvation” (vv.13–14).

“Save us” is a prayer offered in other psalms (Ps 54:1; 80:2; 106:47); the petition appears more often in the singular, “save me” (Ps 7:1; 22:21; 31:16; 54:1; 55:16; 59:2; 69:1; 71:2; 109:26; 119:94, 146; 142:6; 143:9). “Save us” when faced with danger is the prayer of the elders of Israel as they faced the Philistine army (1 Sam 4:3) and the all the people a little later (1 Sam 7:8), David when the ark was put in place in Jerusalem (1 Chron 16:35), Hezekiah when Judah was being threatened by the Assyrians (2 Ki 19:19), as well as the prophet Isaiah at the same time (Isa 25:9; 33:22; 37:20).

This prayer in the context of festive celebrations—the context for which Psalm 118 appears to have been written—expresses the firm confidence of the people, trusting in the power of their God. That viewpoint is perfectly applicable to the Palm Sunday story (and even more so to the Easter Sunday narrative!).

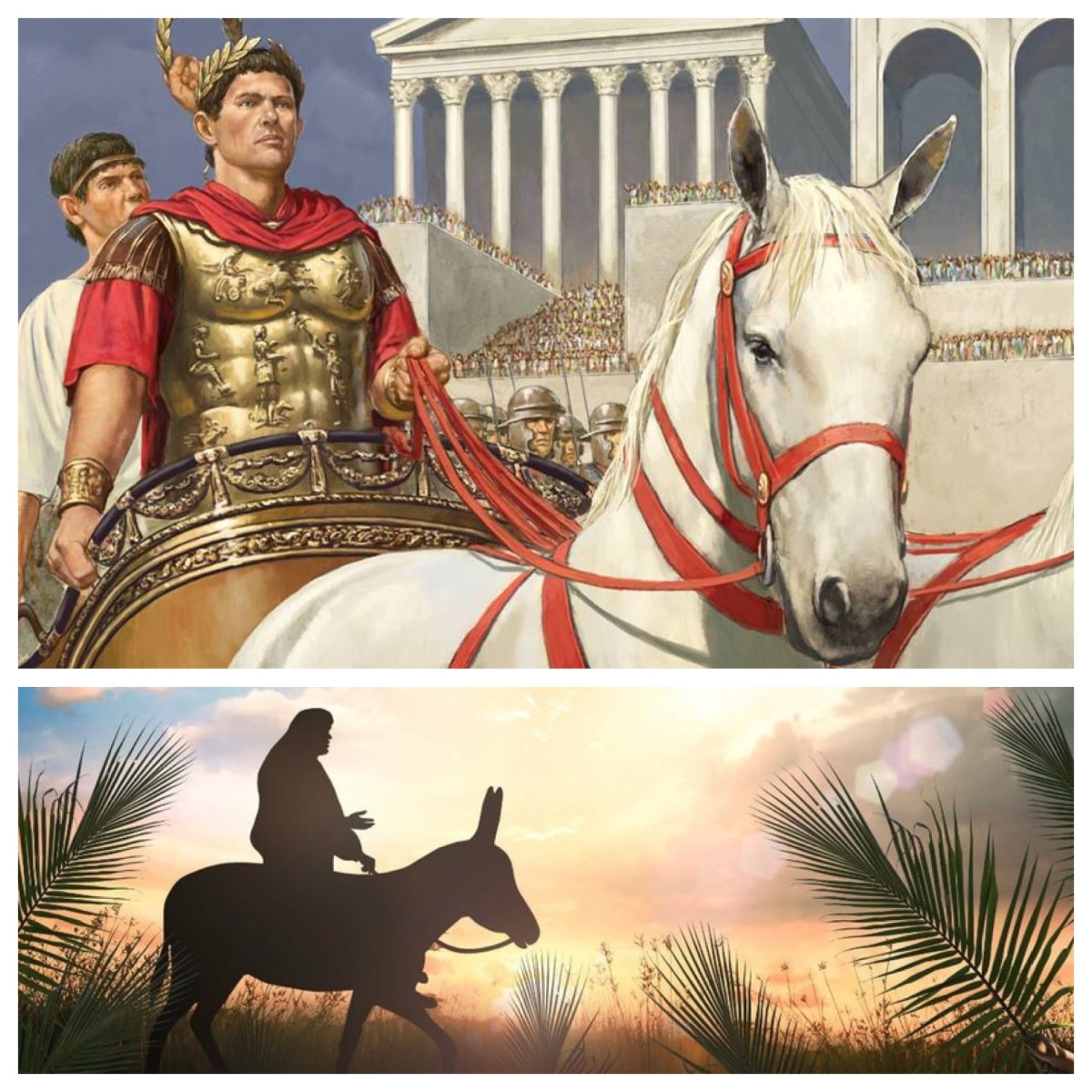

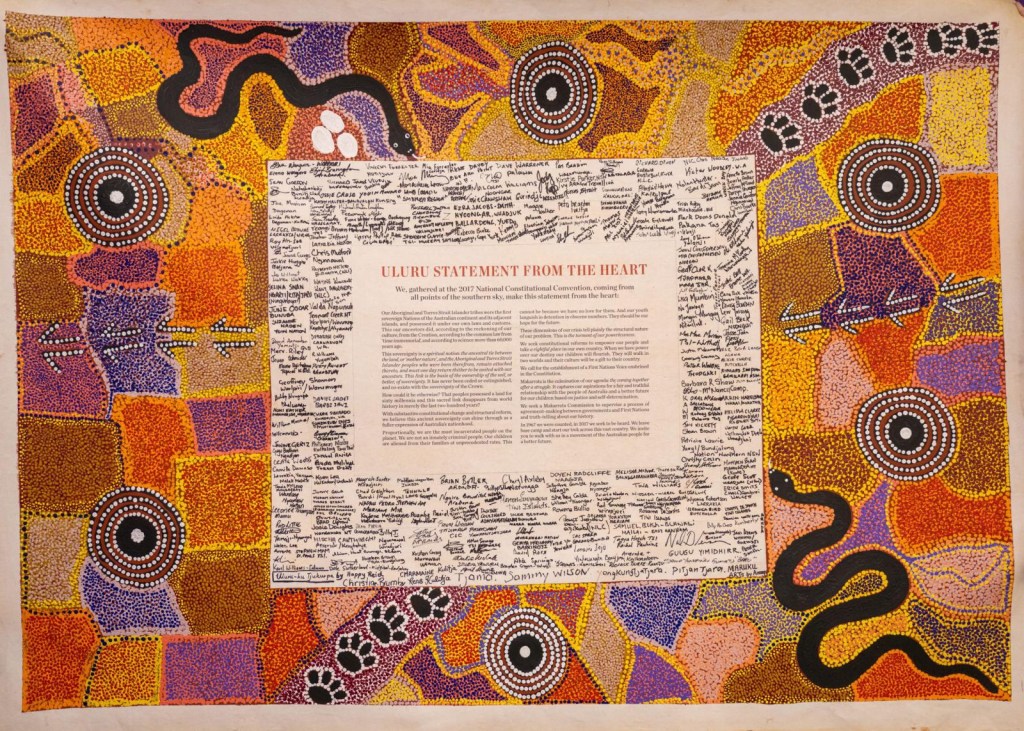

But this psalm is not only a prayer of celebration; it is also a strong statement about the resilience and trust of the people, expressing their belief that God will give them redemption, even in the face of their Roman overlords, who had held political and military power for many decades. If this is what the crowd intended with their cry as Jesus enters the city—and I have no reason to see otherwise—then this is a striking, courageous political cry embedded in the story! It is a cry that affirms that salvation is at hand.

*****

Salvation is what is in the mind of the people as they cry, “save us” (v.25) and the earlier affirmation, “I thank you that you have answered me and have become my salvation” (v.21). As we have noted, “save us” was a recurring cry amongst the Israelites. In the song sung after the Exodus, the people acclaim God, singing “the Lord is my strength and my might, and he has become my salvation” (Exod 15:2). In his song of thanksgiving after battles with the Philistines, David praises God as “my rock, my shield and the horn of my salvation” (2 Sam 22:3; also vv.36, 47, 51; and 1 Chron 16:23, 35).

The same language, of salvation, appears in the psalms (Ps 13:5; 18:2, 35, 46; 24:5; 25:5; and another 40 times) and the prophets (Isa 12:2–3; 25:9; 33:2, 6; 45:8, 17; 46:13; 51:5–6; 52:7, 10; 56:1; 59:11; 61:10; 62:11; Mer 3:23; Mic 7:7; Hab 3:18). From the psalms, we remember “the Lord is my light and my salvation” (Ps 27:1); from Isaiah, “I will give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (Is 49:6).

There are a dozen occasions in Hebrew Scripture when God is identified as Saviour (2 Sam 22:3; Ps 17:7; 106:21; Isa 43:3, 11; 45:15, 21; 49:26; 60:16; 63:8; Jer 14:8); as the Lord God declares through Hosea, “I have been the Lord your God ever since the land of Egypt; you know no God but me, and besides me there is no Saviour” (Hos 14:4).

Salvation is linked with righteousness; “the salvation of the righteous is from the Lord … he rescues them from the wicked and saves them” (Ps 37:39–40). Being righteous is a quality of the Lord God (Ps 11:7; 35:28; 50:6; 71:16; 85:10; 89:16; 97:2, 6; 103:17; 111:3; 116:5; 119:137, 152; 129:4; Isa 45:21; Jer 23:6; 33:16; Dan 9:16; Zeph 3:5) which is thus desired of those in covenant with God (Gen 18:19; 1 Sam 26:23; 2 Sam 22:21, 25; 1 Ki 10:9; 2 Chron 9:8; Job 29:14; Ps 5:8; 9:8; 11:7; 33:5; Prov 1:3; Isa 1:27; 5:7; 28:17; 42:6; 61:11; Jer 22:3; Ezek 18:5–9; Hos 10:12; Amos 5:24; Zeph 2:3; Mal 3:3).

It is no surprise, then, that this psalm celebrates that “[God] has become my salvation” (Ps 118:21) by holding a “festal procession with branches” (v.27), entering through “the gates of righteousness” (v.19) and proceeding all the way “up to the horns of the altar” (v.27), singing “save us, Lord” (v.25) and “blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord” (v.26). This is a high celebratory moment!

So the closing verses take us back to the opening refrain, “O give thanks to the Lord, for he is good, for his steadfast love endures forever” (v.29; see also vv.1–4). The celebration is lifted to the highest level, with praise and thanksgiving abounding. And that makes this a perfect psalm for Palm Sunday!

****(

On the indications of the political nature of the Palm Sunday scene, see