Jesus had a mission to the Gentiles. The mission to the Gentiles was “the fundamental missionary dimension of Jesus’ earthly ministry”—so wrote the guru of modern missiological studies, David Bosch (Transforming Mission, p. 30). And thus, every theology of mission since that paradigm-shifting work of 1991 has echoed this claim as a given fact.

But when we turn to this week’s Gospel passage, we read that Jesus instructed his followers: “Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 10:5-6). What is going on?

This is a very distinctive claim to make. Other New Testament books have a different take—Jesus did engage with Gentiles, even with Samaritans, and did encourage a mission to the wider Gentile world. And plenty of New Testament texts can be pulled out to support this claim.

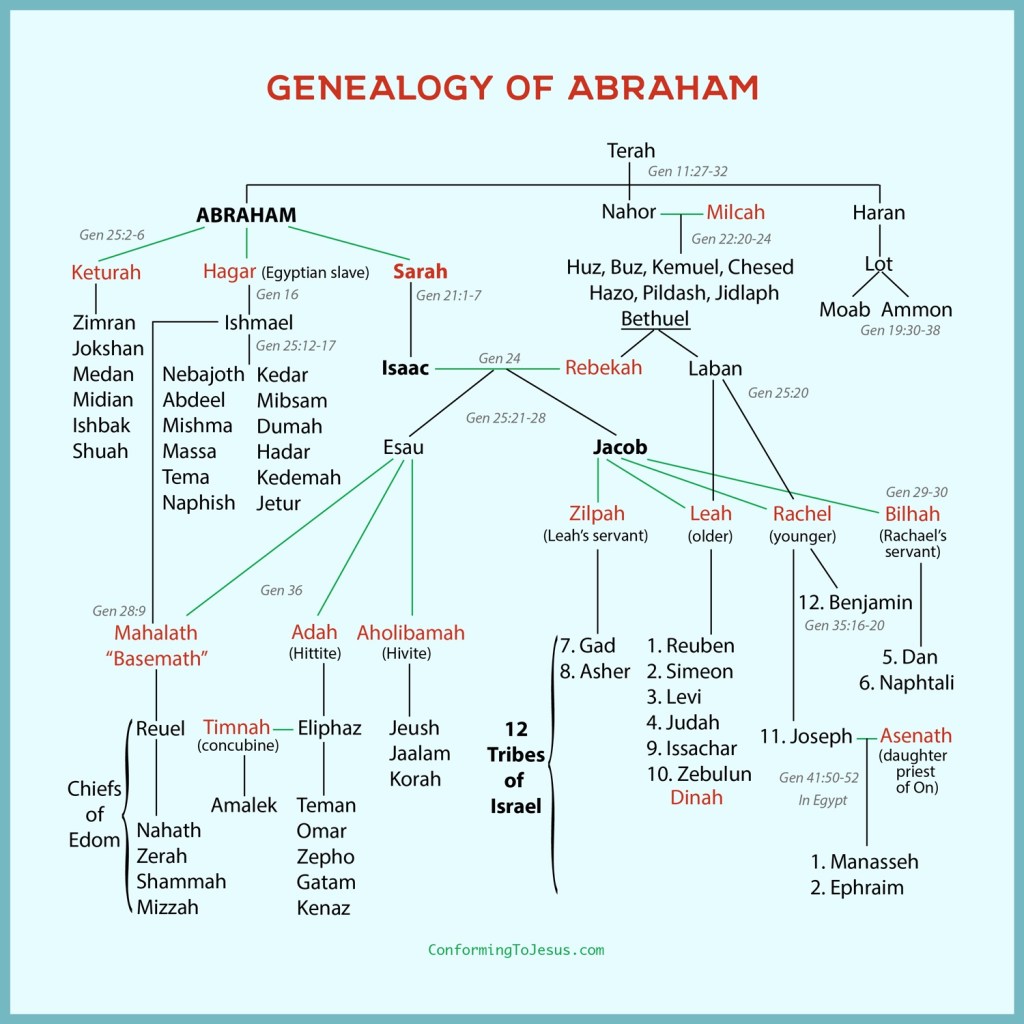

In Mark’s Gospel, in the story of the Gadarene demoniac (Mark 5:14–21), the healed man begs to be taken with Jesus. Jesus tells him to go home, and spread the story of the Lord’s mercy. This he does throughout the Decapolis—which was Gentile territory! The first evangelist, according to Mark, was a missionary to the Gentiles.

The Matthean Jesus, unlike the Lukan Jesus, never goes near Samaria (Luke 17:11–19), nor does he speak favourably about Samaritans, as he does in Luke (10:25–37), prefiguring the Lukan mission to Samaria (Acts 1:8; 8:4–25).

And in John’s Gospel, the first person who tells many others about Jesus is a woman whom Jesus meets when he is travelling through Samaria (John 4:5–26). After her discussion with Jesus, “the woman left her water jar and went back to the city, and said to the people, ‘Come and see a man who told me everything …he cannot be the Messiah, can he?’” (John 4:28–29). As a result of what she says, “many Samaritans in that city believed in him” (John 4:39); the first evangelist in John’s narrative is a Samaritan wo

Not in Matthew’s Gospel, however. Jesus does not go amongst Gentiles. Or Samaritans. Just as the disciples of Jesus are entirely drawn from Jewish people in Matthew’s Gospel, so also Matthew makes it very clear that Jesus’ mission is “only to the lost sheep of Israel”—that is, exclusively to the Jewish people.

My wife Elizabeth and I have had many conversations about this aspect of the Gospel according to Matthew. She has undertaken thorough research into the Jewish nature of this Gospel, and especially on how Jesus related to Gentiles. What follows is drawn from our conversations and particularly from the research of Elizabeth, as we have written this material together.

*****

The section of the book of origins that we are offered as the Gospel reading this coming Sunday (Matt 9:35–10:8) ought to be familiar. The first verse (9:35) is an almost-exact repeat of an earlier verse (4:23). The same three activities of Jesus are noted—teaching, proclaiming the good news, and curing disease. The earlier verse introduced the activity of Jesus in Galilee; this later version broadens the area where Jesus was active to “all the cities and villages”.

However, Jesus is still in Jewish territory; he had returned “to his home town” earlier (9:1) and emphasises that his followers are not to go into Gentile territory (10:5)—an instruction which he presumably maintains himself, for he tells them “go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (10:6) and later affirms that “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (15:24).

This neat repetition of the whole verse that provides an inclusio—a literary device which bundles together all the material in between the two occurrences of the same sentence. The extended set of teachings that Jesus gave (5:—7:29), as well as the healings (8:1–17; 8:28–9:8; 9:18–34) are collated into a broader and comprehensive introduction to the mission of Jesus, which, as he indicates soon after, is to the Jews only (10:5).

Also included in this section is the call of Matthew (9:9), to match the earlier call of the first four disciples (4:18–22), and the warnings that Jesus issues about the difficulty of following him (8:18–21), which is followed by Jesus stilling the storm (8:22–27), which climaxes in the key question, posed by the disciples, “What sort of man is this, that even the winds and the sea obey him?” (8:27; the allusion is to a psalm praising the Lord that, amongst other things, “you silence the roaring of the seas, the roaring of their waves, the tumult of the peoples” (Ps 65:7).

Matthew finds a report of the mission of the twelve in one of his sources, the Gospel we attribute to Mark (Mark 6:8–11). The statement about going “only to the lost sheep of Israel” (10:5–6), in the mission directives to the twelve disciples, is clearly an addition to the original Markan passage. In this distinctive Matthean statement, Jesus directs that Gentile (and Samaritan) towns are to be avoided.

There is, as we have noted, a second statement to this effect in this Gospel, when Jesus encounters a Gentile woman on the northern borders of Galilee. This also is a clear redactional addition to an account already found in Mark (Mark 7:24–30). In Matthew’s version, he declares, “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 15:24). There is nothing of this in Mark’s report of this encounter.

A third Matthean statement about mission, the “Great Commission” (28:16–20), is completely different, as the disciples are commanded to go out and actively “make disciples of all nations”. This command correlates with nothing at all in the body of the Gospel, during the earthly period of Jesus’ life. The mission to the Gentiles is an entirely post-resurrection phenomenon.

So the two major statements of mission to Israel in this Gospel, as well as other accounts of the activities and ministry of Jesus, contain a number of significant differences to that of Mark and Luke. The ministry of both Jesus and the disciples is geographically quite limited in Matthew’s account.

*****

Jesus rarely sets foot on any Gentile soil in this Gospel. In Matt 15:29–31, there is no tour through Sidon and the Decapolis as is reported in Mark (Mark 7:31–37), and no missionary activity undertaken by the demoniac after the demons have been exorcised from him (Mark 5:1–20; compare Matt 8:28–34).

The Matthean Jesus never goes near Samaria (contrast with Luke 17:11–19 and John 4:1– 42), nor does he speak favourably about Samaritans, as he does in Luke (Luke 10:25–37), prefiguring the Lukan mission to Samaria (Acts 1:8; 8:5-25). The activities of Jesus and the disciples are concentrated in the Galilean area, and on the Jewish people.

In Matthew‘s account, there are no Gentiles who are intentionally sought out by either Jesus or the disciples. Rather, there are just a select number of Gentiles who seek out Jesus. They come to him; he does not approach them or seek them out. (I am indebted to Elizabeth for this striking observation.) In two instances, it is their faith which includes them in the kingdom of God (the centurion in Capernaum, 8:10, 13; the Canaanite woman in Tyre and Sidon, 15:28).

Ultimately, Jesus says to the Jews, “the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people that produces the fruits of the kingdom” (21:43). He is not here saying that the kingdom will be opened to the Gentiles per se; his words are directed towards the chief priests and Pharisees (as 21:45 indicates).

It is those Jews who “produce the fruits of the kingdom” who will be given entry to the kingdom. Those who do “produce the fruits of the kingdom” include those normally considered as “unclean” by the Pharisees, and therefore outcasts or rejects from Judaism (9:10–13; 21:31, 32).

Jesus’ discourses and acts of healing, in general, involve only Jews. His contact with Gentiles, when it occurs in the Gospel, is always highly significant, and designed to illuminate some aspect of Jesus’ teaching or person regarding authority, inheritance of the kingdom, discipleship or messiahship.

It is noteworthy that those occasions when a person is asked whether they have faith before Jesus will heal them, are only when Gentiles are involved. Jesus readily heals Jewish people without requesting a prior faith statement (4:24; 8:3; 8:15; 12:13; 12:22; 14:36; 15:31; 21:14).

*****

More recent Matthean scholarship has recognised the Jewish character of this Gospel, and a consensus is emerging that this work was most likely written for a community that was still immersed within its Jewish tradition. It appears that members of this community had been ostracised and persecuted by other Jews (including their families) who did not believe Jesus to be the Messiah. They did not withdraw voluntarily from their local synagogues, but still operated as a group under Jewish authority (10:17; 23:34).

This community is still directly under Jewish law; the clear words of Jesus that are remembered and repeated are “the scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat; therefore, do whatever they teach you and follow it” (23:1-3). That law is not to be abolished, but fulfilled (5:17); it remains “until all is accomplished” (5:18).

In the teachings of Jesus which are recalled in this community, their faithfulness in the midst of persecution is valued (5:10–12); they report that Jesus identifies this persecution as taking place “on my account” (5:11; see also 10:18, 39; 16:25; 19:29). Thus the difference between this community and many other Jews of the time was the belief that Jesus was the promised Messiah.

Judaism was in a state of flux in the middle to late decades of the first century. The pivotal moment looks, from the benefit of hindsight, to have been the a Jewish-Roman War of 66-74 CE, and particularly the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple which took place in 70 CE, in the middle of this war.

Things were different after the Temple was rendered unusable. That is often taken as a marker for understanding events in the period of the New Testament, certainly, it is a key marker for understanding the major shifts that took place within Judaism—with no Temple in place, the importance of synagogues as gathering places in towns and cities across Israel (and beyond) grew.

What little evidence we do have from this general period indicates that there were a number of sectarian groups within Judaism, which were contesting with each other for recognition and influence. During this period, the Pharisees were becoming increasingly important as an alternative to the Temple cult, and emerging as the dominant Jewish religious movement. Their power base was moved from Jerusalem and spread throughout the area. They were well-placed to take advantage, as it were, of the situation when the Temple no longer served as a focal point for Jews.

Nevertheless, many Jews, particularly in the Diaspora, were not yet “Pharisaic”—they did not see their faith in the same way as the Pharisees. There were many disputes amongst Jewish communities as to the correct way of seeing things, and some of these disputes were quite bitter.

Many groups claimed to be the ‘true Israel’ as distinct from other groups, who were false leaders and teachers, and who failed to follow the Law correctly. The Law became the most accessible means of revealing God’s will for Israel after the destruction of the Temple, and most of these groups focused on what they believed to be the true interpretation and application of it.

The synagogues were the places where the Law was studied and discussed, where it was preached and understood. The synagogue was where the scribes and Pharisees most naturally operated. The Pharisees thus grew in significance over time. They had established synagogues decades before Jesus was born. After 70 CE, synagogues became the key gathering place for Jews, both within Israel, and across the Dispersion.

*****

Matthew’s Gospel reflects one such debate, between the authorities in the synagogues and the followers of Jesus. Biblical scholars suggest that this Gospel should be read alongside of other literature from after the time of the destruction of the Temple—books such as 2 Baruch, 4 Ezra, and the Psalms of Solomon. This literature is trying to envisage what Judaism should be like in the aftermath of the destruction of the Temple. Understanding and living by the Law is central in each of these documents.

Thus, although Matthew’s Gospel has been seen to have played an important role in the formation of early Christian theology, a more natural interpretation is to locate this Gospel within the first century Jewish debates about how the Law is best to be understood and applied.

These debates took on even more intensity after 70 CE. The survival of Judaism without the Temple depended on the faithful practice of the Law: all of its commandments and instructions. The polemic in Jesus’ debates with the Pharisees, and the warnings that are uttered to Israel, show that Matthew still had hope that his ideas would become normative for all Jewish people.

If the author of this Gospel knew anything about what was happening elsewhere, he would have known about the gathering strength of the movement led by Saul of Tarsus, for whom strict obedience to Torah was of less importance than belief in Jesus as Messiah.

This arm of the movement was opening a door wide for Gentiles, who did not follow the Torah, to belong to such communities. This had been underway since the 50s. It had gained momentum by the late 60s and would become the dominant form of Christianity later in the second century.

It was perhaps with this awareness that Matthew’s Gospel was created—to insist on the centrality and priority of the traditional teaching of Jesus, the Torah-observant Jew, whom God had chosen as the anointed one. And the picture that he offers of Jesus is a resolutely Jewish one. Remembering that Jesus said “Go nowhere among the Gentiles” (10:5) makes perfect sense in this context.

(In fact, I think that this Gospel might more accurately reflect the activity of the historical Jesus during his earthly activities—he was a faithful Jew who observed Torah and advocated for his particular interpretation of how the commandments were to be kept. Staying away from Gentiles and Samaritans would be a perfectly respectable course of action for such a person.)

So, in reporting the words of Jesus about mission, and in insisting on the thoroughly Jewish nature of this movement, this really is “the book of origins”. This is how I translate the opening phrase (1:1). Usually this phrase is related to the story that follows, about the origins of Jesus (1:1–2:23). And that makes sense.

In a broader sense, however, the author of the book of origins is making a pitch about the true nature of the movement that was formed by Jesus.

Jesus instigated a prophetic movement to renew the people of Israel, to recall them to the prophetic heart of their traditions and restore the sense of righteous-justice that was fundamental to his understanding of Judaism. That is the real story of our origins, the author of this book is declaring.

******

This blog draws on material in MESSIAH, MOUNTAINS, AND MISSION: an exploration of the Gospel for Year A, by Elizabeth Raine and John Squires (self-published 2012)

See also

https://johntsquires.com/2019/11/28/leaving-luke-meeting-matthew/

https://johntsquires.com/2020/02/13/you-have-heard-it-said-but-i-say-to-you-matt-5/

https://johntsquires.com/2020/02/06/an-excess-of-righteous-justice-matt-5/

https://johntsquires.com/2020/01/30/blessed-are-you-the-beatitudes-of-matthew-5/