Psalm 119, the longest of all psalms, is the 176–verse grand acrostic of the Hebrew Scriptures (22 sections of eight verses each, commencing in order with the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. A small portion of this psalm (119:105–112) is offered by the lectionary this coming Sunday. I am exploring the questions: what would a theology look like, using only the verses in this psalm? and how full (or inadequate) would that theology be? See earlier instalments at

4 Relationship to God

Like all of the psalms, this psalm indicates a firm belief that God can be directly involved in the life of the believer. This is yet another topic which features in a fully-developed theology. The author invites God to “turn to me and be gracious to me, as is your custom toward those who love your name” (v.132); there is a clear sense that God is at hand, hearing the song, and willing to respond.

In one section (vv.81–88), the author sounds a classic lament, indicating that they are languishing, feeling “like a wineskin in the smoke” (v.83); they are persecuted, facing pitfalls, “they have almost made an end of me on earth” (v.87). Yet although they fear their life (v.88), they endure, with hope, and keep “watching for your promise” (v.82).

Confidence in God’s ability to intervene and strengthen the person of faith is expressed in a multitude of ways throughout this psalm. The psalmist prays, “revive me according to your word” (v.25), and is grateful to report that when “I told of my ways, you answered me” (v.26).

“Confirm to your servant your promise, which is for those who fear you”, the psalmist prays (v.38), offering a hope that God will “give me life” (v.37, 107, 154). This is a hope that is regularly expressed throughout the psalm: “in your righteousness, give me life” (v.40), “your promise gives me life” (v.50), “I will never forget your precepts, for by them you have given me life” (v.93), and “consider how I love your precepts; preserve my life according to your steadfast love” (v.159).

The mutuality of this relationship (as befits the covenantal relationship) is well-expressed in the couplet, “in your steadfast love, hear my voice; O Lord, in your justice, preserve my life” (v.149). The confident trust that the psalmist has in God is declared in the affirmation, “great is your mercy, O Lord; give me life according to your justice” (v.156). The intensity of this desire is articulated by the affirmation, “in your steadfast love, spare my life, so that I may keep the decrees of your mouth” (v.88).

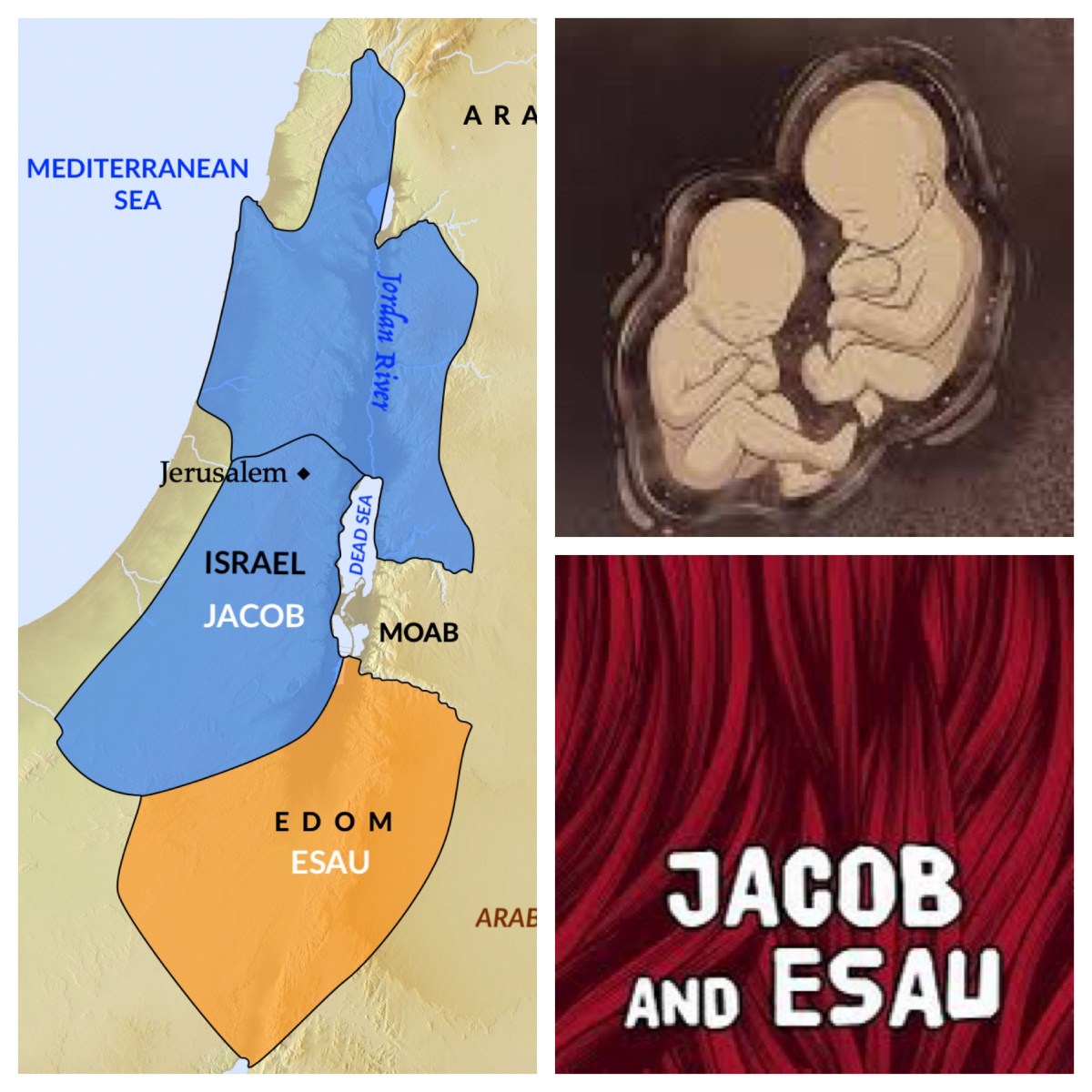

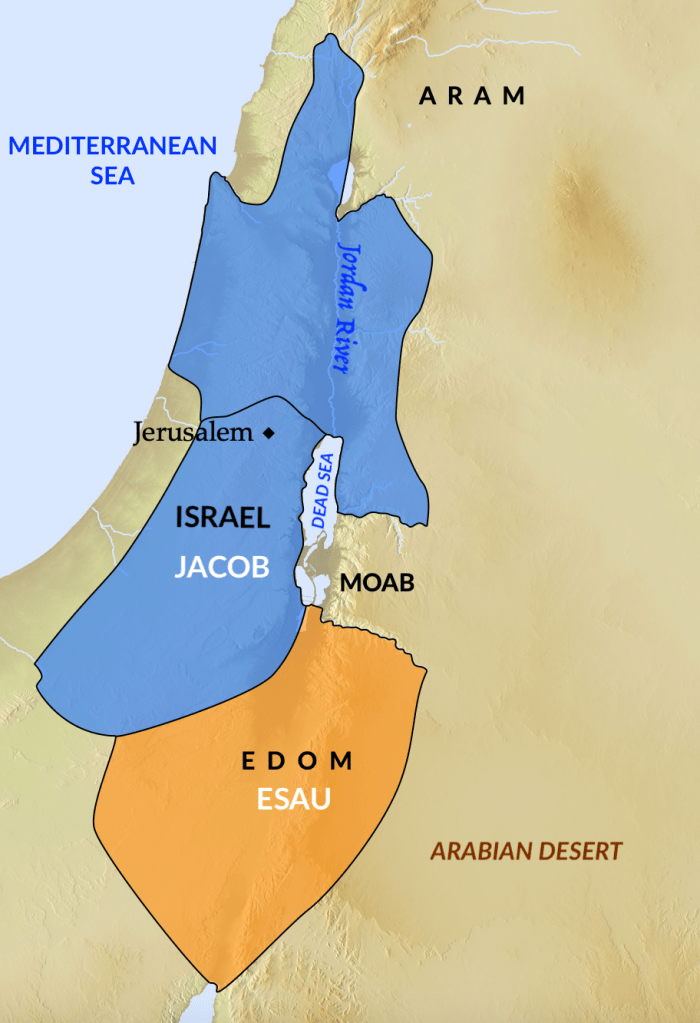

The psalmist has this deep confidence in their personal relationship with God, for “this blessing has fallen to me” (v.56), echoing the favoured situation that was enjoyed by many in the past who were blessed by God: Noah and his progeny (Gen 9:1), Abram (Gen 12:1–3; 24:1), Isaac (Gen 25:11; 26:12), Jacob (Gen 27:23–29; 28:1; 35:9), Joseph (Gen 48:15–16), the twelve tribes (Gen 49:28), and then all the people who journeyed in the wilderness and entered the land (Deut 2:7; 7:14; 28:1–6)—and, of course, in the foundational creation story, all human beings themselves (Gen 1:28; 5:2).

On the basis of this deep confidence, the psalmist therefore asks God, “I implore your favour with all my heart; be gracious to me according to your promise” (v.58) and “turn to me and be gracious to me, as is your custom toward those who love your name” (v.132). Those who love the name of the Lord are also described, in typical scriptural terms, as “those who fear you” (vv.38, 63, 74, 79, 120). More often, the psalmist relates their love, not directly for God, but for God’s commandments (vv.47–48, 127), decrees (vv.119, 167), precepts (v.159), and law (vv.97, 113, 163, 165).

Quite characteristically, the psalmist looks to the Lord to teach—after all, the root sense of Torah is actually teaching, as already noted. “Put false ways far from me and graciously teach me your law” (v.29) is the psalmist’s prayer; “teach me your way” (vv.12), or “your ordinances” (v.108), or most often, “your statutes” (vv.26, 33, 64, 68, 124, 135, 171). Such teaching will provide and enlarge understanding (vv.32, 34, 73, 125, 144, 169).

The psalmist is clear that “the unfolding of your words gives light; it imparts understanding to the simple” (v.130), and so they are able to assert, “through your precepts I get understanding” (v.104), and, indeed, “I have more understanding than all my teachers, for your decrees are my meditation” (v.99).

This is an active, engaged deity, relating directly with the person singing this lengthy prayer. God relates specifically through the words of Torah, yes; but nevertheless, those words draw the psalmist into a close relationship with the Lord God—a relationship that feels intimate, a relationship that is based on solid trust and firm confidence.

On the basis of this confident trust in God, the psalmist affirms, “you are my hiding place and my shield; I hope in your word” (v.114), and again, “my hope is in your ordinances” (v.43). So the psalmist prays for God to “remember your word to your servant, in which you have made me hope” (v.49) and “my [whole being] languishes for your salvation; I hope in your word” (v.81).

The motif of hope is consistently expressed throughout: “uphold me according to your promise, that I may live, and let me not be put to shame in my hope” (v.116), “I rise before dawn and cry for help; I put my hope in your words” (v.147), and “I hope for your salvation, O Lord” (v.166).

The relationship with God that the psalmist demonstrates throughout is strong, trusting, confident, and hope-filled. It is an intensely personal relationship—which puts to lie to the terrible discriminatory caricature of Jews in the past having no personal relationship with God, and feeling weighed down by the demands of the Law.

5 Revelation in Torah

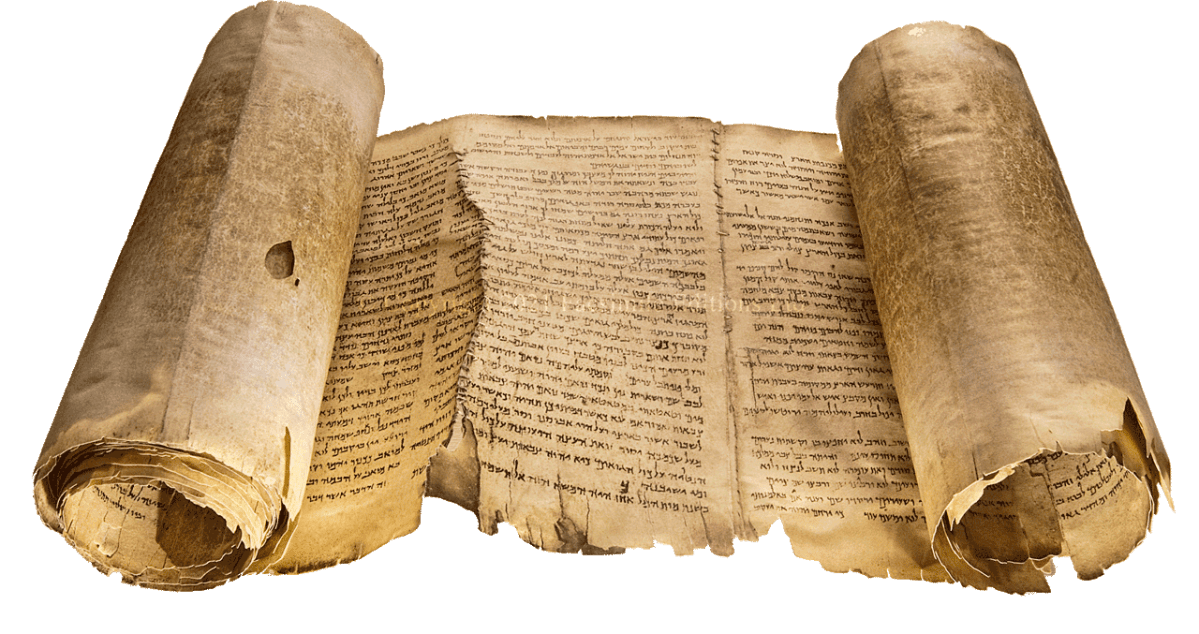

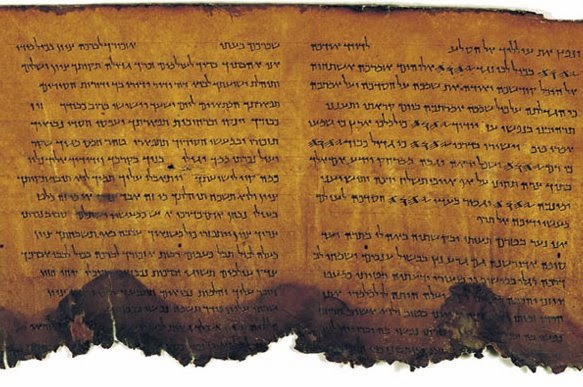

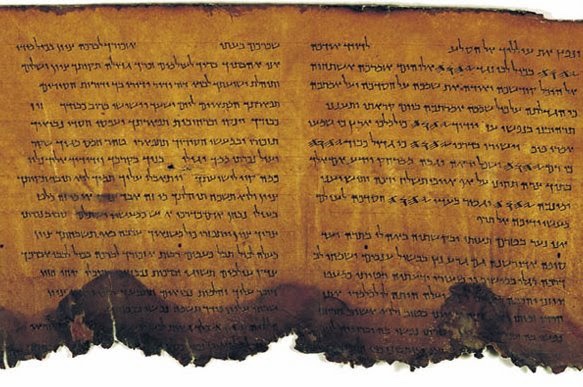

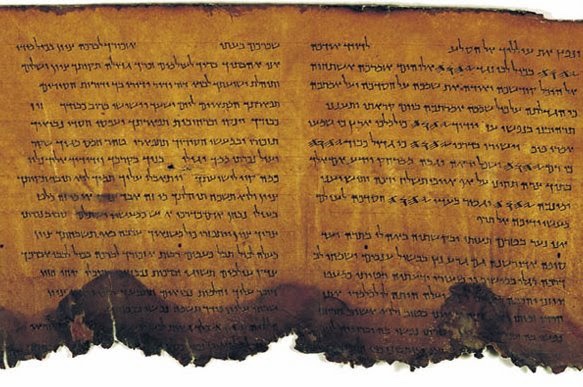

What is striking about this psalm is that at every point, the understanding of God, and the expectation that God will relate closely to faithful human beings, is grounded in Torah. Torah was the essence of what God gave to Moses on Mount Sinai, and which Moses then passed on the people of Israel (Exod 19:1–9; 24:12–18; Deut 4:45–46; 6:1–9).

The psalmist values, appreciates, and is committed to Torah in every aspect that they are aware of. Torah does not oppress or bind; on the contrary, Torah gives life and offers salvation.

The psalm is thoroughly embued with the presence of Torah; this is the means by which God communicates to those singing and hearing the psalm. Not only does every one of the 8–verse stanzas of the psalm contain references to Torah, but also, a set of eight related words are deployed in ever-changing sequences of synonymous parallelism within each section. The most commonly word used, of course, is Torah, translated as law. It occurs 25 times in the 176 verses.

Synonymous with Torah (and, indeed, describing elements of it) are decrees (23 times), statutes (22), precepts (21), commandments (20), promises (15), and ordinances (14). The eighth word is word itself, appearing 21 times—most famously in the verse, “your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path” (v.105), which is often used in Christian liturgies to introduce the reading of scripture.

(If you add up the statistics in the previous paragraph, you find that there are 161 occurrences of these words for Torah; and as there are 176 verses in the psalm, this means that one of this cluster of terms appears in almost every single verse!)

This recurrent use of a set of synonyms expands the pattern that is found in the second section of Psalm 19, where the terms law, decrees, precepts, commandment, ordinances (and “fear of the Lord”) appear in parallelism in a section praising Torah (Ps 19:7–10).

Of this Torah, the psalmist affirms the word from God very early on, “I have commanded your precepts to be kept diligently” (v.4), to which they respond, “O that my ways may be steadfast in keeping your statutes!” (v.5). This way that is to be taught is important; “teach me, O Lord, the way of your statutes, and I will observe it to the end” (v.33).

The term way, of course, appears in the very first verse of the psalm as a synonym for those “who walk in the law of the Lord” (v.1) and then recurs a further six times (vv.9, 14, 27, 30, 32, 33). This is in contrast to “every evil way” (v.101), “every false way” (v.104, 128). It is the same contrast that expressed so succinctly in another psalm, “see if there is any wicked way in me, and lead me in the way everlasting” (Ps 139:24).

“The Way” is important in the story of Israel: both the way in the wilderness, escaping from Egypt and heading towards the promised land—“the way that the Lord had commanded you” (Exod 32:8; Deut 9:16; 13:5; 31:29); and also the way out of Exile, back across that wilderness—“the way of the Lord“ which is to be prepared, to make way for “the glory of the Lord [to] be revealed” (Isa 40:3–5).

In Proverbs, the sage declares that “the way of the Lord is a stronghold for the upright, but destruction for evildoers” (Prov 10:29), whilst the prophet Jeremiah equates “the way of the Lord” with “the law of the Lord” (Jer 5:4–5), and Ezekiel compares the righteous “way of the Lord” with the unrighteous ways of sinful Israel (Ezek 18:25–29; 33:17–20).

Seven times the psalmist refers to the “righteous ordinances” or “righteous commandments” of the Lord, including, “you are righteous, O Lord, and your judgments are right (v.137); “the sum of your word is truth; and every one of your righteous ordinances endures forever” (v.167); and “seven times a day I praise you for your righteous ordinances” (v.164).

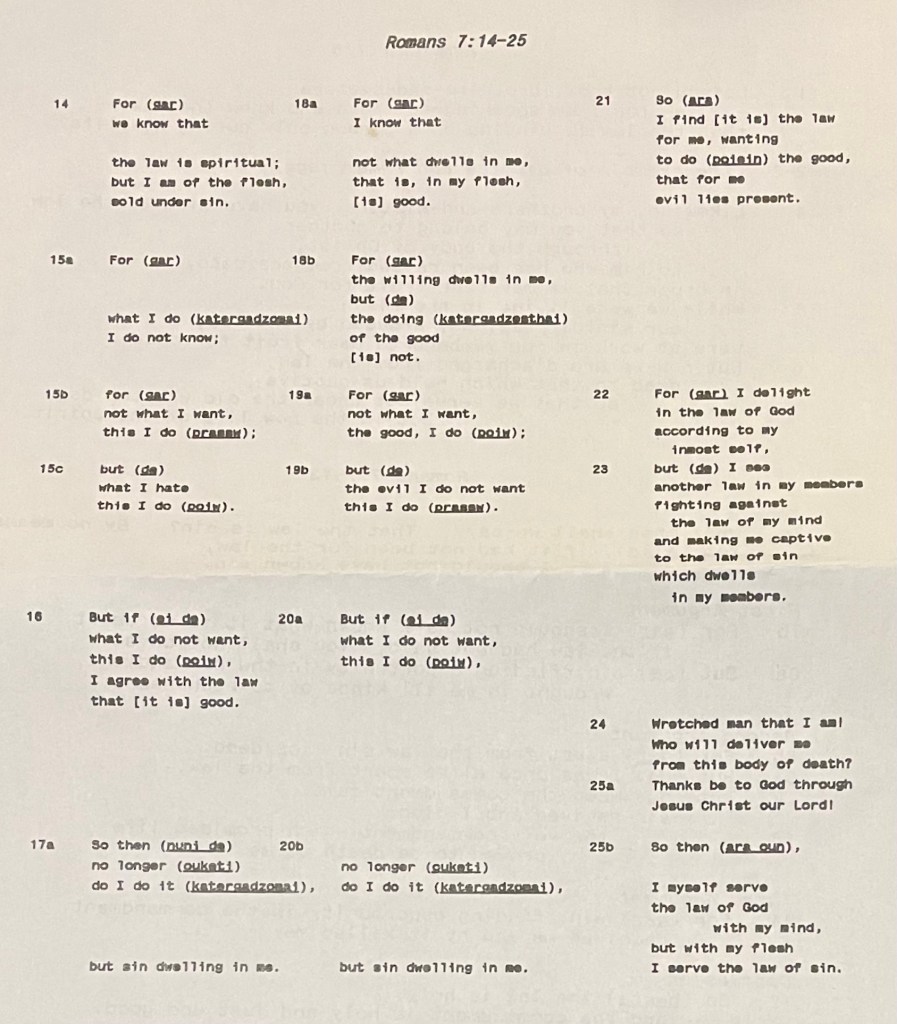

Three times, the truth of Torah is affirmed as “the word of truth” comes from the mouth of God (v.43), “your law is the truth” (v.142), and “you are near, O Lord, and all your commandments are true” (v.151). In many ways, Torah functions as a central pivot in this psalm in the same way that “the word of the cross” functions as the central theological claim in Paul’s letters, and indeed the Gospels; and the way in which “the Bible” has a determinative, guiding, and even controlling role in Protestant evangelical theologies. This is how God can best be known, and this is what guides and informs the life of the believer.

*****

The final post is at