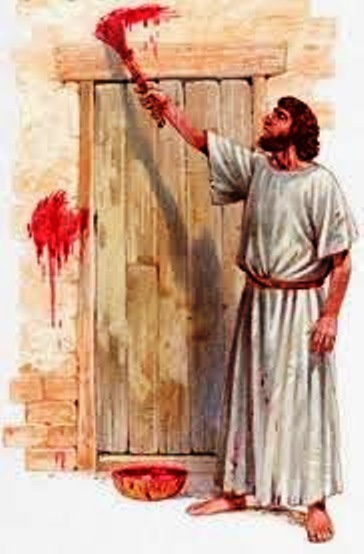

The instructions are clear: “take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and the lintel of the houses in which they eat it” (Exod 12:7).

The explanation is also clear: “I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and I will strike down every firstborn in the land of Egypt, both human beings and animals … the blood shall be a sign for you on the houses where you live: when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and no plague shall destroy you when I strike the land of Egypt” (Exod 12:12–13).

It’s a story of hope, expressed in joy; and it’s a story about death, filled with despair. We will hear it this Sunday, as it is offered as the Hebrew Scripture reading for Pentecost 15 (Exodus 12:1–14). It all depends on where you stand as you hear the story. Are you in the shoes of the escaping Hebrews? Or in the shoes of the Egyptians who saw their beloved children slaughtered?

The story that is told about the Exodus in the Hebrew Scriptures is a story filled with hope. It tells of the liberation of an oppressed people, suffering under the burdens of forced labour; it recounts the sequence of events that led to the miraculous escape from slavery, crossing through the Sea of Reeds, travelling unhindered through the wilderness, into a land which the story claims was promised by God—a promised land, gifted to a chosen people by a holy God.

The story that is told in the Hebrew Bible about the Exodus is also a story filled with violence. There is the violence executed in Pharaoh’s actions in having the young boys murdered. There is the violence that is threatened by the Egyptian army as their chariots and horses thunder in hot pursuit of the escaping Israelites.

Worse, there is the insistent violence in the series of increasingly damaging plagues which God is said to have sent against the Egyptians. And finally, there is the climactic and catastrophic violence of the surging of waters over the army and their horses, as they as swamped and drowned in the middle of the Sea of Reeds.

It is a difficult story to take at face value; what sort of people remember such a tale of incessant violence? and what sort of a God takes sides with one group of people and acts in such a vicious way against their opponents? Furthermore, how can we accept this story as part of our canon of scripture, when it is so filled with violent act after violent act?

This is not the only place that we encounter violence in the Hebrew Scriptures; as the story goes on, it proves to be one of invasion, massacre, colonisation, and dispossession of people in the land of Canaan; and then, a string of battles take place in various locations, as the invading Israelites gradually exert their dominance over the indigenous people of the land.

All of this violence is indeed of deep concern, and it can be seen to place the whole of those scriptures under a cloud. However, I don’t want to fall into the supercessionist trap, the approach taken in the second century by Marcion of Sinope, who discarded the whole of the Old Testament—and, indeed, a significant part of the New Testament! We have these stories as part of our scriptures, and we need to hear them, ponder them, and engage critically with them.

Nor do I want to gloss over the fact that acts of violence, both those committed by human beings, and those attributed to the Lord God, can be found in many parts of the New Testament. It is a ubiquitous problem. Violence is expressed in many texts in scripture—both Jewish and Christian—and, indeed, is found in the texts of many other religious traditions. Human beings live, and die, by violence. We can never escape it, it seems.

If we take these texts as a literal account of historical events, we have significant theological issues to address. And there are a number of difficult historical questions that must be addressed, if we want to hold to the claim that Exodus is reporting an historical “as it really happened”. Where is the evidence for the escape of a huge number of people at that time? (There is none.) Who was the Pharaoh of the time? (There are two very different suggestions about this.)

What about the evidence for the huge crowd that spent 40 years in the desert? Where are the bones of the dead, the remains of campsites, from that crowd, if that is accepted to be the massive crowd 600,000 males (plus their women and children) that would set forth into the wilderness (see Exod 12:37) and then their descendants? There is absolutely no evidence for these archaeological remains, at all.

But such a forensic historical interrogation is not my approach to the story of the Exodus, nor to other parts of Hebrew Scripture, nor, indeed, to the narratives found in the New Testament.

So my approach to these texts has been to undertake an appreciative enquiry approach: what is this text saying? what drives the energy of the writer? what issues of concern do I read and hear—explicitly in the words used, and implicitly, in between and under what is said? what elements can I affirm, as contributing constructively to the Hebrew Scriptures’ understandings of God? and, as a consequence of that, to the New Testament’s understandings of God?

To begin, we need to recognise that the Exodus was seen as the paradigm for liberation—political, cultural, social, religious—which has shaped Jewish life for millennia. It is no wonder that it was picked up as a key motif for early followers of Jesus, to describe his significance: preaching the kingdom of God, the righteous-justice of a compassionate God, a challenge to the collective political, social, and religious status quo, and a liberating way of being for those following him.

A group of priests in the exile in Babylon collected and collated materials from earlier traditions, and developed a series of stories that conveyed in saga form the key elements of their national story. Symbolism and poetry were the paramount features of these stories, originally oral, later written on scrolls.

In the latter stages of the Exile or perhaps in the early stages of return to the land and rebuilding society, the stories and sagas were drawn into the set of scrolls we know as the Torah, the first part of the TaNaK. Symbolism featured prominently in these poetic stories and narrative rehearsals of the past.

The Passover occupies a central place in the long, sweeping narrative that is told in Hebrew Scripture. As well as the story of the Passover which led to the exodus from Egypt (Exod 12–15) and the thrice-documented priestly regulations governing the annual celebration (Lev 23:4–8; Num 28:16–25; Deut 16:1–8), the story is told of celebrating Passover at key moments in that ongoing narrative: at the foot of Mount Sinai (Num 9:1–14), at Gilgal when about to enter the land of Canaan (Josh 5:10–12), when the Temple worship was restored under Hezekiah (2 Chron 30:1–27), and during the great reformation that took place under Josiah (2 Ki 23:21–23).

The priest-prophet Ezekiel, in his vision of the restored land and new Temple, seen during the Exile, insists that the Passover be celebrated on a recurring annual basis (Ezek 45:21–25). Even though the Temple that was eventually rebuilt was of a different size and shape, when the Exiles returned under Darius, the Passover was celebrated at the dedication of the rebuilt Temple (Ezra 6:19–22).

Over time, interpreters under influence from later developments in thinking began to “reify” and “historicise” these symbolic sagas and develop the idea that they reported “events that actually happened”. They didn’t—as we have noted, there is no evidence outside the Bible for the sequence of events found in the Exodus saga. But the story had a potency for these priestly writers as the land was restored, the Temple rebuilt, society reconstructed.

The Passover story, leading up to the escape of the Exodus, that Jews recall and relive each year and which Christians remember on a regular basis in the eucharistic celebration, tells the age-old scapegoat dynamic in a dramatic story filled with symbolism. It too was not an historical event, but a story developed to explain the special significance of the people of Israel and their faith in a god who took extraordinary steps to secure their freedom.

Of course, within the emerging Jewish movement that had a focus on Jesus as an authoritative teacher of the Torah, a key way of grappling with the fact that Jesus was put to death as a criminal, hung on a cross under the orders of the Roman Governor, was to draw on this story of blood shed, lambs sacrificed, and salvation gained.

The timing of the death of Jesus is placed within the Passover festival by all four canonical Gospels. That is the festival that remembers the story of what happened to Israel, long ago—and that passes on the story that this happens year-in, year-out, as the faithful people of Israel remember and relive their national salvation.

One Gospel even locates the actual hour when Jesus dies on the cross as being “on the day of preparation for the Passover” (John 19:14, 31). Jesus, already identified in this Gospel as “the lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world” (John 1:29, 36), dies when the Passover lambs are being slaughtered in preparation for the Passover meal that evening. (The other three Gospels, of course, place the last meal of Jesus with his disciples at the Passover meal—Mark 14:12–25 and parallels—and thus, in their chronology, he dies on the day after Passover.)

Jesus is remembered as the “paschal lamb … who has been sacrificed” (1 Cor 5:7); it is by the shedding of his blood that atonement with God takes place (Rom 3:25), that faithful people are justified (Rom 5:9), that peace is achieved (Col 1:20), that redemption occurs (Eph 1:7). One writer makes much of this, emphasising that this redemption is eternal (Heb 9:12; 13:20), opening up “a new and living way” (Heb 10:19–20). It is his shed (sprinkled) blood makes Jesus “the mediator of a new covenant” (Heb 12:24) and that his faithful people are sanctified (Heb 13:12).

So this ancient story, passed down by word of mouth and then written in scrolls that themselves were passed down for reading and understanding, sits deeply within the self-understanding of both Jewish and Christian people. It is a story we cannot avoid.