At this time of the year, as we celebrate the birth of Jesus at Christmas, the beloved story from Luke’s Gospel, with census, donkey, manger, shepherds, and angels, is the dominant biblical text that most churchgoers will hear. Perhaps it is closely followed by the highly-developed theological interpretation that begins John’s Gospel. The Matthean account of the wrath of King Herod and the visit of the Magi has its place, twelve days after Christmas, at Epiphany.

Other biblical passages come a long way behind these Gospel texts. Yet, as I have noted in other posts, the Revised Common Lectionary does provide a series of additional passages, drawn from the psalms and the prophets, as well as the epistles, for worship on and around Christmas. These passages are offered for the Nativity of the Lord as Proper I, Proper II, and Proper III. See

Each of these passages provides another way for us to celebrate the Christmas event; they are clearly supplementary rather than primary in their function. As I have sought to explain, the psalms provide celebratory songs, while the prophetic passages offer hope and promise. Alongside these, the epistle passages proposed by the lectionary serve a different function.

It is well-known that Paul makes very little reference to the life of Jesus in his letters. His focus is intently on the death and resurrection of Jesus, rather than the teachings and miracles, parables and exorcisms, debates and disputations, that we read about in the canonical Gospels.

For Paul, it is the twofold statement that “Christ Jesus, who died, yes, who was raised” (Rom 8:34), the claim that Jesus “gave himself for our sins to set us free from the present evil age” (Gal 1:4), the affirmation of “the redemption that is in Christ Jesus” (Rom 3:4), and the hopeful declaration that “Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him” (Rom 6:9), which is the heart of the message he proclaims. This death-resurrection movement also forms the basis of his credal exposition at 1 Cor 15:3–8.

One of the few places where Paul clearly describes something in the life of Jesus other than this death-resurrection complex is in the Epistle passage that is provided by the lectionary for the first Sunday after Christmas (Gal. 4:4–7). Here, Paul acknowledges that Jesus was “born of a woman, born under the law” (Gal 4:4). This is a slightly more developed claim than is made in Romans, where he acknowledges that Jesus “was descended from David according to the flesh” (Rom 1:4).

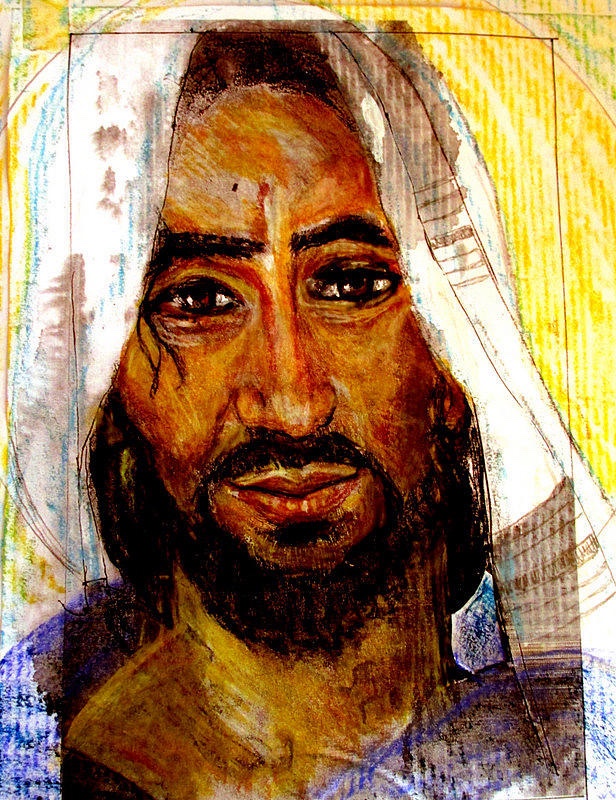

This passage from Galatians is offered because it provides the earliest confessional statement about the birth of Jesus (since Paul wrote this letter to the Galatians decades before the Gospels were written). What he says is concise and clear: Jesus was “born of a woman, born under the law”. The first phrase indicates that Jesus was a human being—born of a woman, like all of us. That is an affirmation made explicit in the fourth Gospel (John 1:14) and which undergirds the narratives of the three Synoptic Gospels.

The second phrase indicates that he was a Jew—born into a society that valued and appreciated the law that long had shaped the practices and customs of the Jews. The Jewishness of Jesus is described with clarity at so many points in each of the Gospels, in which he attends synagogue on the sabbath, demonstrates his detailed knowledge Torah, and takes part in festivals in Jerusalem. The Johannine Jesus affirms that “salvation is of the Jews” and the Synoptic Jesus lays claim to the command to “love God … and love your neighbour” as the key element of his teaching.

This is a fundamental element in our Christian confession; in the Apostles’ Creed, we affirm that we believe in Jesus, “born of the virgin Mary”. Paul says nothing here about Mary’s status, other than she was a Jewish woman. Apart from the passing reference in verse 4, Paul’s focus is not so much on the fact that Jesus was born a Jew, but on the significance of the birth of this child.

So he writes that Jesus was born “in order to redeem … so that we might receive adoption” (Gal 4:5), and goes on to say more about adoption, inheritance, and the receiving of the Spirit as a child of God (Gal 4:6–7). For Paul, the creation of the human family that is presumed by his statement (infant and mother; and father, although not mentioned here) also means the creation of a wider, larger family of faith, of each one of us who is “an heir through God”. Which is, of course, why believers celebrate with joy each Christmas.

In the resources offered by the lectionary for Christmas, in the three sets of readings for the Nativity of the Lord I, II, and III, we have three excerpts from Epistles which provide similar insights—fleeting, incomplete, not fully developed—about the coming of Jesus and the significance of this event. (None of these passages refer to the “birth” of Jesus, nor do they refer directly to Jesus by name; each of them offers allusion and inference, rather than direct description.)

For Proper I, a brief affirmation is offered: “the grace of God has appeared, bringing salvation to all” (Titus 2:11). The allusion to the birth of Jesus may well be deduced; the precise wording is generalised and remote from “the birth of Jesus”. That Jesus is “the grace of God” might well be argued from other scriptural texts (John 1:17; Rom 1:5; 5:2, 15; 1 Cor 1:4; Eph 1:6–8; 1 Tim 1:14; 2 Tim 1:9) but is not made explicit in this brief statement in Titus 2.

For Proper II, another excerpt from the same epistle notes that “when the goodness and loving kindness of God our Saviour appeared, he saved us, not because of any works of righteousness that we had done, but according to his mercy, through the water of rebirth and renewal by the Holy Spirit” (Titus 3:4–5). Strikingly, the appearance of the kindness of God is here portrayed as an act of the Spirit; Jesus is nowhere named or identified!

And for Proper III, an excerpt from Hebrews declares, “in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son, whom he appointed heir of all things, through whom he also created the worlds” (Heb 1:2), and then goes on to articulate a grand vision of this Son (not explicitly named as Jesus).

The author is drawing from language in the Wisdom tradition to state that “[the Son] is the reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being, and he sustains all things by his powerful word” (Heb 1:3). (Of course, Wisdom was feminine in Hebrew Scripture; here, as in other New Testament books, the key features of Wisdom are masculinised as they are applied to the man, Jesus.)

Reflecting God’s glory and being the exact imprint of God, as set forth in this passage, are striking claims. Although they appear in a letter addressed to “the Hebrews”, in which scriptural citations undergird the theological argument proposed, these phrases take us far and away from the Jewish baby born to Mary, into speculative philosophical musings about the eternal nature of the Son.

In these three texts, as in the short excerpt from Galatians 4, claims are made about the consequence of what Jesus achieved. In each case they take us far from the story of the birth of the child

In the first except from Titus, after stating that “the grace of God has appeared”, a standard Pauline catchphrase follows (“who gave himself for us”; see Gal 1:4; 2:20; and see Eph 5:2) followed by references to redemption from iniquity (still Pauline; see Rom 3:24; 8:23; 1 Cor 1:30), before adding “and purify for himself a people of his own who are zealous for good deeds” (Titus 2:14). The reference to purification and the affirmation of “good deeds” has moved us far from Paul, and tells us nothing additional about Jesus, the Jewish infant.

The next excerpt from Titus (3:7), noting “when the goodness and loving kindness of God our Saviour appeared”, describes the consequences of this appearance. The author here uses terms that are thoroughly Pauline. First, “he saved us” (see Rom 1 Cor 1:18; Rom 1:16; 10:1; 13:11; Phil 2:22); second, “having been justified by his grace” (see Rom 3:24; 5:1–2; Gal 2:15–21); and third, “that we might become heirs” (see Rom 8:15–17; Gal 3:28–29). Then the writer adds “according to the hope of eternal life”. Paul himself does refer to “eternal life” (Gal 6:8; Rom 2:7; 5:21; 6:22–23), although this is a very Johannine idea. But once again, we are far from the infancy born to Mary “under the law”.

In the excerpt from Hebrews, after offering the Wisdom-inspired cosmic vision of the Son, the writer declares, “when he had made purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high” (Heb 1:3). Again, such a statement redirects attention away from the birth of the infant, and his Jewish origins, into the heavenly realm, far away from earth (according to the ancient cosmological understanding).

My sense is that these three Epistle readings offer elements which have been taken up into the development of Christological thinking; but they offer little in the way of deepening our appreciation of the actual “story of Christmas” which is, inevitably, the focus in worship services at Christmas.