Last Sunday we heard the story of David’s adultery with Bathsheba (2 Sam 11:1–15). In the passage that we hear this Sunday (2 Sam 11:26—12:13), the prophet Nathan regales him with a tale of a rich man with “very many flocks and herds” and a poor man with “nothing but one little ewe lamb” who was much loved and was “like a daughter to him” (12:1–3).

See

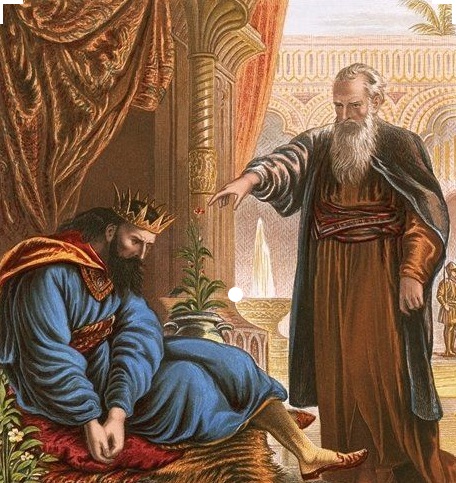

Nathan’s story ends with a powerful punchline: “he took the poor man’s lamb, and prepared that for the guest who had come to him” (12:4). The point is clear; the rich man has acted unjustly. David immediately erupts in anger at the selfish acts of the rich man. “As the Lord lives”, he exclaims, “the man who has done this deserves to die” (12:5). And yet, after a lengthy diatribe from the prophet, speaking forth the word of the Lord to the king (12:7–14), David changes his tune.

“I have sinned against the Lord”, David says to Nathan, who then reassures him, “now the Lord has put away your sin; you shall not die” (12:13). Nathan has executed his prophetic role with power: calling David to account. At least the king recognises his sin and repents. God both punishes and forgives him.

Reflecting on the nature of repentance, and forgiveness, we are led to ponder Psalm 51: “have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love; according to your abundant mercy blot out my transgressions”, the psalmist sings. The first half of this song (Ps 51:1–12) is offered by the lectionary as the Psalm for this coming Sunday.

The ascription at the head of this psalm makes the traditional connection with David (as is also the case with 72 other psalms in the book), and provides a specific occasion for the writing of this psalm: “when the prophet Nathan came to him, after he had gone in to Bathsheba”. It would seem that the psalm first this occasion quite neatly.

This is one of a dozen psalms that each has an ascription which relates the particular song to an incident in David’s life: “when he fled from his son Absalom” (Ps 3; 2 Sam 15); “when the Lord delivered him from the hand of all his enemies and from the hand of Saul” (Ps 18; 2 Sam 22); “when he pretended to be insane before Abimelech, who drove him away, and he left” (Ps 34; 1 Sam 21); “when Doeg the Edomite had gone to Saul and told him, ‘David has gone to the house of Ahimelech’” (Ps 52; 1 Sam 22); “when the Ziphites had gone to Saul and said, ‘Is not David hiding among us?’” (Ps 54; 1 Sam 23); “when the Philistines had seized him in Gath” (Ps 56; 1 Sam 21); “when he had fled from Saul into the cave” (Ps 57; 1 Sam 22); “when he fought Aram Naharaim and Aram Zobah, and when Joab returned and struck down twelve thousand Edomites in the Valley of Salt” (Ps 60; 2 Sam 8); “when he was in the Desert of Judah” (Ps 63; 1 Sam 22–23); and “when he was in the cave” (Ps 142; 1 Sam 22).

Whether any of these ascriptions do report the actual incident that motivated the psalm—or whether the historical note was added subsequently by a later person, on the basis that “this seems to fit”—we cannot definitively say. So whether this particular ascription for Ps 51 is historically accurate or not, it does provide an appropriate insight into the emotions that the writer presents, on an occasion when deep grief and profound contrition appears to have been stirred up.

If this psalm was written by David after he had raped Bathsheba, it could well indicate a profound transformation, from the all-powerful monarch to the humbly repentant sinner. If it is (as many scholars believe, on the basis of language and style) a later exilic creation, it still expresses the inner this formation that can come to a person of faith when they understand the extent of their sin and seek the loving forgiveness of the Lord. In this latter case, it is a psalm for all of us, when confronted with our sinfulness, and challenged to repent. It is a song that envisages a thoroughgoing moral transformation.

Personally, I am sceptical about the historical value of this ascription. Aside from the specific linguistic criticisms that have been advanced, it does not sit well with the character of David as revealed elsewhere in the historical narratives of 1–2 Samuel. The scheming of the king and the aggression of David’s men in battle after battle, both before and after this incident, do not indicate someone with a deep reflective capacity or a totally transformed personality.

David rose to power, maintained his power, and consolidated his kingdom through brute military force in many battles over the years. His kingship was a reign of sheer power; he was a warrior king. I have surveyed the battles that David was engaged in throughout his time as king in an earlier blog; see

After his confrontation with Nathan, David continues in this vein; he goes on to conclude his war against the Ammonites (2 Sam 12:26–31), refuses to punish Amnon for his rape of Tamar (ch.13), did battle against Absalom when he usurped the throne (chs. 15—18), put down an uprising led by Sheba son of Bichri (ch.20), and fought various battles against the Gibeonites and the Philistines (ch.21) before he dies (1 Ki 2:10). His character as warrior king remains unabated.

It is true that after his confrontation with Nathan, David does show mercy to various men: first, to his third son, Absalom (ch.14), and then to Shimei son of Gera, Mephibosheth the grandson of Saul, and Barzillai the Gileadite (ch.19).

However, it is quite telling that the final remembrance of King David is the list of “the warriors of David” with recounting of some of their exploits (ch.23) and then the census that he ordered (24:1–9)—although this latter act was something that he immediately regretted (24:10). Nevertheless, it seems that his character remains consistent with the warrior king David who raped Bathsheba and ordered the death of Uriah the Hittite.

So is Psalm 51 an authentically Davidic expression of remorse and repentance? J. Richard Middleton believes that, whilst there are some indications that do link this psalm with the narrative of 2 Sam 11–12, there are a number of disjunctures. He outlines his case in a carefully-argued article that compares the two passages of scripture.

“A Psalm against David? A Canonical Reading of Psalm 15 as a Critique of David’s Inadequate Repentance in 2 Samuel 12” (ch.2, pp.26 in Explorations in Interdisciplinary Reading. Theological, Exegetical, and Reception-Historical Perspectives, ed. Robbie F. Castleman, Darian R. Lockett, and Stephen O. Presley; Pickwick, 2017). See https://jrichardmiddleton.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/middleton-a-psalm-against-david-explorations-in-interdisciplinary-reading-20171.pdf

First, Middleton notes that the psalmist pleads to be delivered from death (Ps 51:16), yet David is explicitly told he will not die (2 Sam 12:13). Second, the psalmist envisages that the process of forgiveness will be lengthy and repetitive (Ps 51:1–2, 7, 9), whilst David receives immediate forgiveness (2 Sam 12:13).

Third, the psalmist offers petitions for many different things, but David only “pleaded with God for [his] child; David fasted, and went in and lay all night on the ground” (2 Sam 12:16). Finally, whilst the psalmist confesses “against you, you alone, have I sinned, and done what is evil in your sight” (Ps 51:4), David’s sins (as I have noted in previous blogs) are against Bathsheba and Uriah, as well as “against the Lord” (2 Sam 12:13).

Middleton adds to this the observation that there is a noticeable dissonance between the prose narrative and the poetic song in terms of the extent of moral reformation that follows on from the confession of sin. The psalmist prays “in verse 10 for a pure heart and a steadfast spirit and in verse 12 for a willing spirit—a request that is related to God’s desire for faithfulness in the inner person (which was articulated in verse 6)”.

In contrast to this, Middleton argues (on p.39) that “not only is this request never voiced by the David of the Samuel narrative, it is (more importantly) never fulfilled in David’s life”. He notes that “the David of the narrative certainly has the broken spirit and broken and crushed heart that the psalmist says is a true, godly sacrifice in verse 17”, he nevertheless “does not get beyond this to the moral reformation of character presupposed in the psalm”.

Middleton deduces from this that “while the psalmist is broken and crushed in spirit prior to receiving forgiveness, and so pleads desperately for cleansing and restoration, the David of 2 Samuel is broken and crushed in spirit after receiving forgiveness and remains an ambivalent character for the rest of the Samuel” (p.40). So what the narrator has conveyed in the account of David’s rather knee-jerk (and perhaps superficial) response to Nathan’s confronting words indicates that he falls far short of the personal angst that led the author of Psalm 51 to a deep personal transformation.

Which means both, that we treat with caution the way that David is so lauded and exalted and painted in such a positive way in much of the 1–2 Samuel narrative; and that we appreciate the profound nature of the thoughts and feelings expressed by the psalmist (most likely NOT King David) in Psalm 51. It could well be a psalm that each one of us could pray, at an appropriate occasion.

See also