“Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe” (John 20:25). So Thomas says to the other disciples, gathered in Jerusalem after Jesus had been crucified and buried. In two Gospels, we have a report of Jesus appearing to the disciples (Luke 24:36–49; John 20:19–23).

In Luke’s account, Jesus had invited the disciples to “look at my hands and my feet; see that it is I myself. Touch me and see; for a ghost does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have” (Luke 24:39). In some manuscripts, it is then reported that “when he had said this, he showed them his hands and his feet” (Luke 24:40). That may be the same incident that John reports, although only he notes that “Thomas (who was called the Twin), one of the twelve, was not with them when Jesus came” (John 20:24).

It is later, when the other disciples tell him of the appearance of Jesus to them, that Thomas expresses the doubt for which he is infamous. A week later, he responds to the invitation from Jesus to “put your finger here and see my hands; reach out your hand and put it in my side; do not doubt but believe”, with the words, “my Lord and my God!” (John 20:27–28). From the swirl of doubt emerges the clarity of belief.

Those hands which bore “the mark of the nails” merit some consideration. Bruised and bloodied, scarred forever by the barbarity of crucifixion—what had those hands done? Where had they touched others? How had they been instrumental in the ministry of Jesus?

The one story that specifically reports Jesus using his finger is the “floating” narrative concerning a woman caught in adultery, a group of scribes and Pharisees, and Jesus. (It is a “floating” story because it appears in some version of John’s Gospel, but not in others; and in yet more ancient manuscripts, at three different places in Luke’s Gospel.) The text reports that, when the scribes and Pharisees made their accusation against the woman, “Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground” (John 8:6).

Whilst “the dust of the ground” was the source for God’s creation of humanity (Gen 2:7), the ground on which Jesus, the woman, and those bringing her to be stoned would have been a dusty, dirty ground. That ground had endured the tramping of feet, in sandals, or unshod, and the tramping of animals. That ground would have been the receptacle for excreta from those animals, and perhaps also from humans. It would not necessarily be a clean, swept, healthy environment like we might imagine. And yet, Jesus places his finger in that ground, and writes, amidst the detritus of the earth. A small parable of incarnation?

*****

Not only the fingers of Jesus, but also the hands of Jesus would also come into contact with a number of individuals deemed unclean, or at least regarded as “on the edge” within the Jewish purity system that held sway in his culture. When Jesus encountered a leper in Galilee, he “stretched out his hand and touched him” (Mark 1:41; Matt 8:3; Luke 5:13). According to Lev 13:45–46, the leper should have remained outside the town, at a distance from, and not in contact with, the general population.

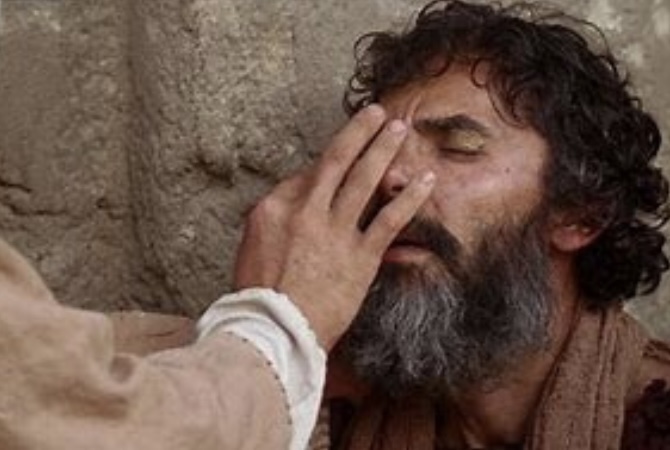

When Jesus approaches Jericho, in Luke’s narrative, he is asked by a blind man to heal him (Luke 18:38–39). Jesus does so, although there is no mention of direct physical contact in this account. In Matthew’s reworking of this story, it is two blind men outside Jericho who beg Jesus, “Lord, let our eyes be opened”, and we are told that “moved with compassion, Jesus touched their eyes” and they were healed (Matt 20:33–33). Likewise, in Luke’s distinctive journey narrative (Luke 9–19), Jesus encounters a bent-over woman in a synagogue; “when he laid his hands on her, immediately she stood up straight and began praising God” (Luke 13:13).

In the Decapolis, the disciples of Jesus brought to him “a deaf man who had an impediment in his speech; and they begged him to lay his hand on him” (Mark 7:32). Mark reports that Jesus “took him aside in private, away from the crowd, and put his fingers into his ears, and he spat and touched his tongue; then looking up to heaven, he sighed and said to him, ‘Ephphatha’, that is, ‘be opened’” (Mark 7:33–34). This was the typical way of operating for healers in the ancient world; Mark reports that Jesus followed this pattern, and “immediately his ears were opened, his tongue was released, and he spoke plainly” (Mark 7:35). Matthew and Luke have no reference to this incident; the thought of Jesus operating like a commonplace healer was not amenable to them (you might say, they couldn’t handle that).

In an incident told only in Mark’s Gospel, a similar way of operating is in evidence. At Bethsaida, “some people brought a blind man to [Jesus] and begged him to touch him” (Mark 8:22). In this encounter, we are told that Jesus “took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the village … put saliva on his eyes and laid his hands on him” (Mark 8:23). Jesus does not shy away from touching the man, and even from placing his saliva on his hand to rub onto the blind man’s eyes, as was the custom of healers. Touch was important.

The same action occurs in a story told only in John’s Gospel, set in Jerusalem; a blind man is healed by Jesus as he “spat on the ground and made mud with the saliva and spread the mud on the man’s eyes” (John 9:6). Jesus was not afraid to breach the boundaries that had been set in place to distinguish clean from unclean. (Saliva, as a bodily discharge, would render a person unclean, according to Lev 22:4–6, 22; and by analogy with the far more detailed prescriptions in Lev 15.) Following the pattern of the healers of the day meant also that the perception of what is clean and what is unclean that Jesus held presented a challenge to these clear boundaries.

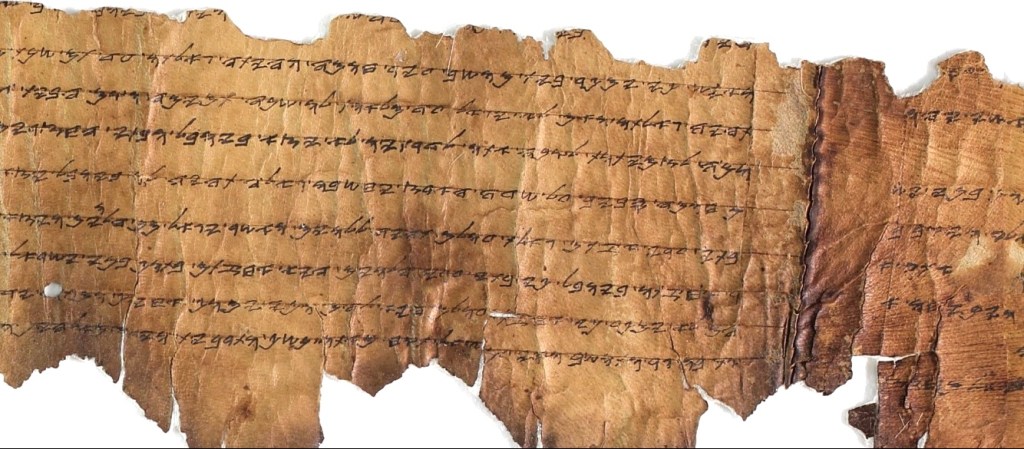

The fingers, and hands, of Jesus move across those boundaries, to connect, reassure, and heal. The Lukan Jesus regards his work as being of God; “if it is by the finger of God that I cast out the demons, then the kingdom of God has come to you” (Luke 11:20). The finger of God was the means by which the plague of gnats took place in Egypt (Exod 8:19), and also the means by which the two tablets of the covenant, tablets of stone, given to Moses on Mount Sinai, had been written (Exod 31:18; Deut 9:10). Jesus claims divine power through the finger of God, as he works to bring in the kingdom of God.

*****

The use of the image of “the finger of God” in the saying of Jesus brings to mind the role that the finger of the priest played in the rituals that took place in the Temple. The priest was to “take some of its blood with his finger and sprinkle it seven times towards the front of the tent of meeting” (Num 19:4; the same instruction is given at Exod 29:12; Lev 4:30, 34; 8:15; 9:9; 14:16, 27; 16:14, 19). The finger of the priest was used to ensure the offering of blood, conveyed directly through touch, that would secure the forgiveness being sought from God.

Whilst Jesus was in the synagogue in his home town of Nazareth, Mark reports that many listening to him were exclaiming, “Where did this man get all this? What is this wisdom that has been given to him? What deeds of power are being done by his hands!” (Mark 6:2). Just as the hands of the priest mediated forgiveness, so the hands of Jesus were instrumental in his healing ministry.

A pattern of regular and direct physical contact with those who were ill was evident: “wherever he went, into villages or cities or farms, they laid the sick in the marketplaces, and begged him that they might touch even the fringe of his cloak; and all who touched it were healed” (Mark 6:56). Matthew changes this observation, noting that “they brought all who were sick to him, and begged him that they might touch even the fringe of his cloak; and all who touched it were healed” (Matt 14:35–36). The initiative in reaching out to touch is reversed in this narrative; Matthew generally preserves a more orthodox Jesus, adhering more carefully to Torah, avoiding direct touch where he can.

Not so for Luke. Early on in his narrative, Luke reports that whilst in Capernaum, as the sun was setting, “all those who had any who were sick with various kinds of diseases brought them to [Jesus]; and he laid his hands on each of them and cured them” (Luke 4:40); and then, a little later, in Galilee, he notes that “a great multitude of people … had come to hear [Jesus] and to be healed of their diseases; and those who were troubled with unclean spirits were cured; and all in the crowd were trying to touch him, for power came out from him and healed all of them” (Luke 6:18–19).

In one incident, Luke claims that “Pharisees and teachers of the law were sitting near by (they had come from every village of Galilee and Judea and from Jerusalem); and the power of the Lord was with him to heal” (Luke 5:17). That explains the transactional significance of direct touch in stories about Jesus as healer; this was the means by which healing power was transmitted between people. Even in Nazareth, where the crowd noted “deeds of power are being done by his hands” (Mark 6:2), and despite their unbelief and offence, “he laid his hands on a few sick people and cured them” (Mark 6:5).

The hands which Thomas later saw—battered and bruised, bloodied by nails being driven through them—were the very hands which mediated the power of God through healings. They were also the hands that were laid on children, as they were brought to Jesus and he blessed them (Mark 10:16, Matt 19:13; Luke 18:15). They were the hands that blessed the disciples, gathered at Bethany after the risen Jesus had been seen, just before “he withdrew from them and was carried up into heaven” (Luke 24:50–51). And these same hands were the hands that were grabbed and bound at his arrest and, later, savagely nailed in preparation for his crucifixion.

*****

There are other hands in the Gospel narratives: the hands of those who attempt to seize Jesus (Luke 20:19; John 7:30, 44; 10:39); the hands of the betrayer and then those who arrest Jesus (Mark 14:41, 46; Matt 26:45, 50; Luke 22:53); the hands of the council members who struck Jesus (Mark 14:65; Matt 26:67; 27:31); the hands of the soldiers who whipped and scourged Jesus (Mark 15:15; Matt 27:26; Luke 22:63; 23:16, 22; John 19:1); the hands of the soldiers who stripped Jesus of his cloak (Mark 15:20; Matt 27:31) and divided his garments, rolling the dice to decide who took which piece (Mark 15:24; Matt 27:35). And the hands of Pilate, blood-soaked, but washed to declare his innocence of that blood (Matt 27:24).

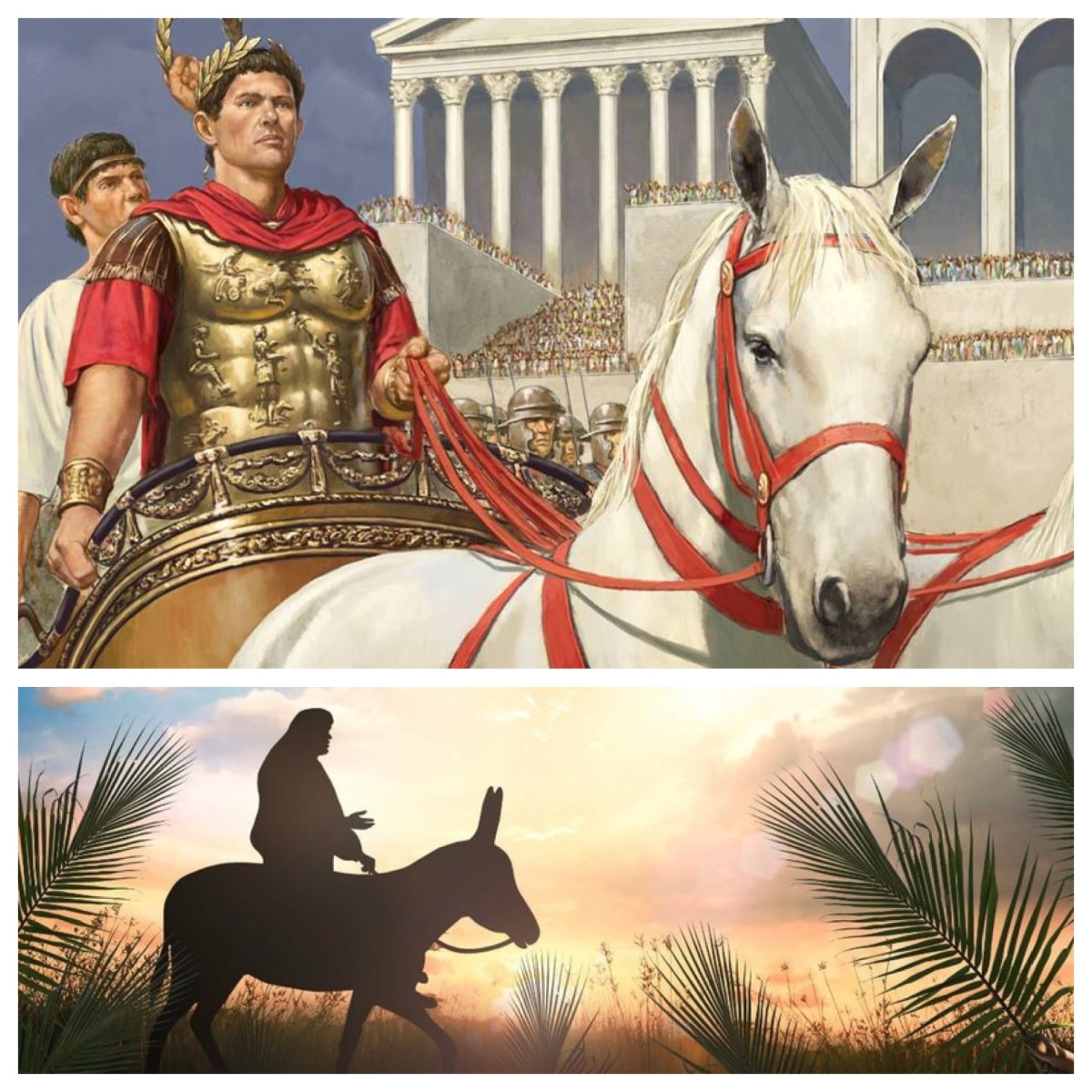

But the focus is on the hands of Jesus in the stories told in the Gospels. The author of the fourth Gospel attests that “the Father loves the Son and has placed all things in his hands” (John 3:35). Later in this Gospel, Jesus says that “the sheep hear my voice; I know them, and they follow me; I give them eternal life, and they will never perish—no one will snatch them out of my hand” (John 10:27–28). The climax to the story in this Gospel is foreshadowed when Jesus, “knowing that the Father had given all things into his hands, and that he had come from God and was going to God” (John 13:3), gathers his disciples for their last meal together.

The author of Luke’s Gospel ends his account of Jesus dying on the cross with Jesus crying out, “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit”, quoting from Psalm 31. Those hands are the ones that the psalmist praises, “long ago you laid the foundation of the earth, and the heavens are the work of your hands” (Ps 102:25, quoted at Heb 1:10; see also Ps 95:4–5); they are the same hands that the psalmist also notes “have made and fashioned me” (Ps 119:73).

The story has traced the full circle, from the hands of God which created all creatures, sent his son into the world, and placed all things into his hands; to the dying son, with hands arms spread wide and his bloodied hands extended, handing back his spirit to God. As Graham Kendrick writes in The Servant King, “hands that flung stars into space, to cruel nails surrendered”.

These hands: reaching out and blessing, touching and healing, wounded and bloodied, scarred, yet offering love; these hands are what Thomas sees.