For questions 1–4, see https://johntsquires.com/2021/12/19/questions-about-christmas-interrogating-the-biblical-story-1/

5 Was Mary riding on a donkey?

In the traditional Christmas story it is a dutiful donkey, a faithful beast of burden, which provides the means of transport for the pregnant Mary on its back. However, nowhere in any Gospel does it say that Mary rode a donkey on that journey. The whole journey is given in three short verses: “All went to their own towns to be registered. Joseph also went from the town of Nazareth in Galilee to Judea, to the city of David called Bethlehem, because he was descended from the house and family of David. He went to be registered with Mary, to whom he was engaged and who was expecting a child.” (Luke 2:3-5).

One of the main reasons why a donkey is associated with the Christmas story is because of the way the story is told in The Protoevangelium of James, an ancient account of Mary’s life that probably originated in the 2nd century, but was not included in the Bible. That text reads: “And there was an order from the Emperor Augustus, that all in Bethlehem of Judæa should be enrolled. And Joseph said: “I shall enroll my sons, but what shall I do with this maiden? How shall I enroll her? As my wife? I am ashamed. As my daughter then? But all the sons of Israel know that she is not my daughter.” “The day of the Lord shall itself bring it to pass as the Lord will.” And he saddled the ass, and set her upon it; and his son led it, and Joseph followed.”

So although this story is an early part of Catholic and Orthodox Church tradition, it does not have the same authority for Protestant believers because it is not in the Bible. Nevertheless, it is quite plausible that Joseph may have obtained a donkey to carry Mary. Donkeys were a common form of transportation (see Matt 21:1–8; John 12:14–15); there are many references to travelling by donkey in Hebrew Scriptures (such as Gen 22:3–5; 44:13; Num 22; Josh 15:17–19; Judges 1:14; 19:28; etc).

Perhaps the strongest influence might have been the story of Moses, travelling from Midian back to Egypt: “So Moses took his wife and sons, put them on a donkey, and went back to the land of Egypt; and Moses carried the staff of God in his hand” (Exod 4:20). So, did Mary travel on a donkey? Quite possibly.

However, most modern biblical scholars say that it is more likely that the Holy Family traveled in a caravan of people. Chris Mueller, in an article for Ascension Press, paints a much different picture. He writes: “Mary and Joseph were not the only ones taking the journey. More than likely, the routes between cities were crowded with travelers. Nobody would consider taking a trip like this alone. It would not have been safe, as the territory between towns was not policed and bandits would have been a real concern. The people probably traveled in great caravans for convenience and safety. Mary and Joseph would have been among the vast migration of people.”

6 Was there really no room left at the local motel?

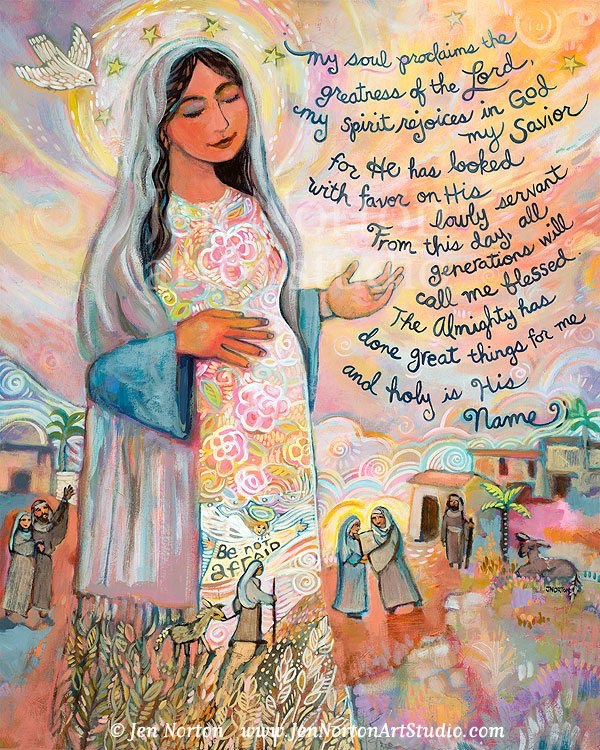

Reading Matthew’s account, we have no clues at all about what happened when Jesus was born. Luke gives just a few details, informing us that Mary “laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn” (Luke 2:7). But that, still, is a rather sparse account. We don’t have the length and weight of the baby and the precise time of birth, like so many proud parents today post on social media!

What was this “inn” that was the birthplace, as Luke maintains, for the infant Jesus? The Greek word used here, κατάλυμα (kataluma), is relatively rare in the New Testament, but appears in many places in ancient Greek literature. It refers usually to a guest chamber or lodging place in a private home. The same term appears in Luke 22:11 with the meaning “guest room,” and the verb derived from this noun appears in Luke 9:12 and Luke 19:7, where it means something like “find lodging” or “be a guest.”

Moreover, in the story of the Good Samaritan, when Jesus refers to the place where the injured traveller rests—clearly a commercial inn—a specific word meaning an inn frequented by travellers is used (pandokian; see Luke 10:34).

So Joseph and Mary were most likely hoping to find shelter with a family member in Bethlehem. That would make sense, given what we know of ancient life; in Jewish society (indeed, in all ancient Mediterranean societies), hospitality was very important. Travel to a town where members of the extended family lived would usually mean staying with them. Unfortunately for them, in the story, once they arrived, they found many other family members had arrived before them. So there was no room in the kataluma, the guest house in the family member’s home.

So banish thoughts of the local Best Western being overflowing, with its flashing neon “No Vacancy” sign. Luke’s story probably suggests that Joseph and Mary were planning to stay at the home of friends or relatives; but the home where they arrived was so full, even the guest room was overflowing, and so they had to be housed with the animals in a lower in the lower part of the house. That was the custom (to house animals in a special section of the house), and that, of course, would be where the manger was to be found.

7 Was Jesus really placed in an animal’s feeding trough?

If we continue to follow the story that Luke tells, then the newborn Jesus is placed into a manger, a trough normally used for feeding household animals. Joel Green believes that Mary and Joseph would have been the guests of family or friends, but because their home was so overcrowded, the baby was placed in a feeding trough. (Green, Luke, NITCNT, 128-29)

Sharon Ringe suggests that “others from a higher rung on the social ladder and in the hierarchy of obligations and honor that characterized Palestinian society had already claimed the space. Not even Mary’s obvious need could dislodge such a firmly implanted order of rights and privileges. Instead of having a guest room, then, Mary, Joseph, and the baby are left to spend their nights in Bethlehem in the manger area where the birth has taken place.” (Ringe, Luke: Westminster Bible Companion, 42)

There is even an old tradition going back to Justin Martyr (who lived 100–165CE), who says it occurred in a cave where animals were housed (Dialogue with Trypho 78). “But when the Child was born in Bethlehem, since Joseph could not find a lodging in that village, he took up his quarters in a certain cave near the village; and while they were there Mary brought forth the Christ and placed Him in a manger, and here the Magi who came from Arabia found Him. I have repeated to you what Isaiah foretold about the sign which foreshadowed the cave.”

Justin claims that by being born in a cave, Jesus fulfils the prophecy of Isaiah 33:16, “he shall dwell in the lofty cave of the strong rock; bread shall be given to him, and his water [shall be] sure”. However, although this verse refers to a cave, there is nothing at all about any birth in that cave.

Nevertheless, the story stuck; Origen refers to it in his work Against Celsus (“there is shown at Bethlehem the cave where He was born, and the manger in the cave where He was wrapped in swaddling-clothes. And this sight is greatly talked of in surrounding places”, 1.51). The cave as the place where Jesus was born is included in the narratives of the Protoevangelium of James (Joseph “found a cave there, and led her into it; and leaving his two sons beside her, he went out to seek a midwife in the district of Bethlehem”, 17–18) and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (an angel “commanded the blessed Mary to come down off the animal, and go into a recess under a cavern, in which there never was light, but always darkness, because the light of day could not reach it”, ch.13).

Was the manger a feeding trough in a cave? or in an outhouse? Robert Tannehill returns to the story of the kataluma, noting that “moving to the manger might take only a few steps, if we assume a one-room farmhouse where the family quarters might be separated from the animal quarters only by being on a raised platform.” (Tannehill, Luke: Abingdon New Testament Commentaries, 65).

Darrell Bock writes that “in all likelihood, the manger is an animal’s feeding trough, which means the family is in a stable or in a cave where animals are housed.” (Bock, Luke: IVP New Testament Commentary, 55). Bock notes the rhetorical ploy of drawing a clear contrast between “the birth’s commonness and the child’s greatness”; perhaps this influenced Luke to provide this particular narrative detail?

So it is plausible that there were animals in near proximity when Jesus was born; the feeding trough suggests an animal shelter. The most commonly pictured animals in traditional nativities, the ox and donkey, are introduced in later apocryphal texts, and most likely draw from the statement by Isaiah that “the ox knows its owner, and the donkey its master’s crib” (Isa 1:3), even though this statement was spoken in a very different context.

*****

There are some longer and more technical discussions at https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/jesus-wasnt-born-in-a-stable-and-that-makes-all-the-difference/ and http://www.hypotyposeis.org/papers/Carlson%202010%20NTS.pdf

*****

See also https://johntsquires.com/2021/12/21/questions-about-christmas-interrogating-the-biblical-story-3/

and https://johntsquires.com/2021/12/22/questions-about-christmas-interrogating-the-biblical-story-4/