This coming Sunday, in the narrative we have been following in the Hebrew Scripture readings proposed by the lectionary (2 Sam 18:5–33), we come to Absalom, the third son of David; or, at least, we come to the aftermath following the death of Absalom, when “ten young men, Joab’s armor-bearers surrounded Absalom and struck him, and killed him” (2 Sam 18:15). These young men were under the command of Joab, a nephew of David who was the commander of his army.

The narrative reports that “Joab sounded the trumpet, and the troops came back from pursuing Israel … they took [the body of] Absalom, threw him into a great pit in the forest, and raised over him a very great heap of stones” (18:16–17). The narrator later reports that David, on hearing of the death of Absalom, “was deeply moved, and went up to the chamber over the gate, and wept”; the lament he offered appears heartfelt: “O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!” (18:33). It evokes his similarly moving lament on the earlier death of Jonathan (2 Sam 1:19–27). See

Over the past eight Sundays, we have been offered a selection of incidents in the life of David. We began with the anointing of David to be king to follow Saul, the first king of Israel (1 Sam 16). We have learnt of the battles that David led against a number of different people—most notably, the Philistines, in the famous confrontation with Goliath (1 Sam 17), seeking to ensure the kingdom of Israel survived. We have heard his deep love for Jonathan, the son of Saul, and his grief at their deaths (1 Sam 18–20; 2 Sam 1).

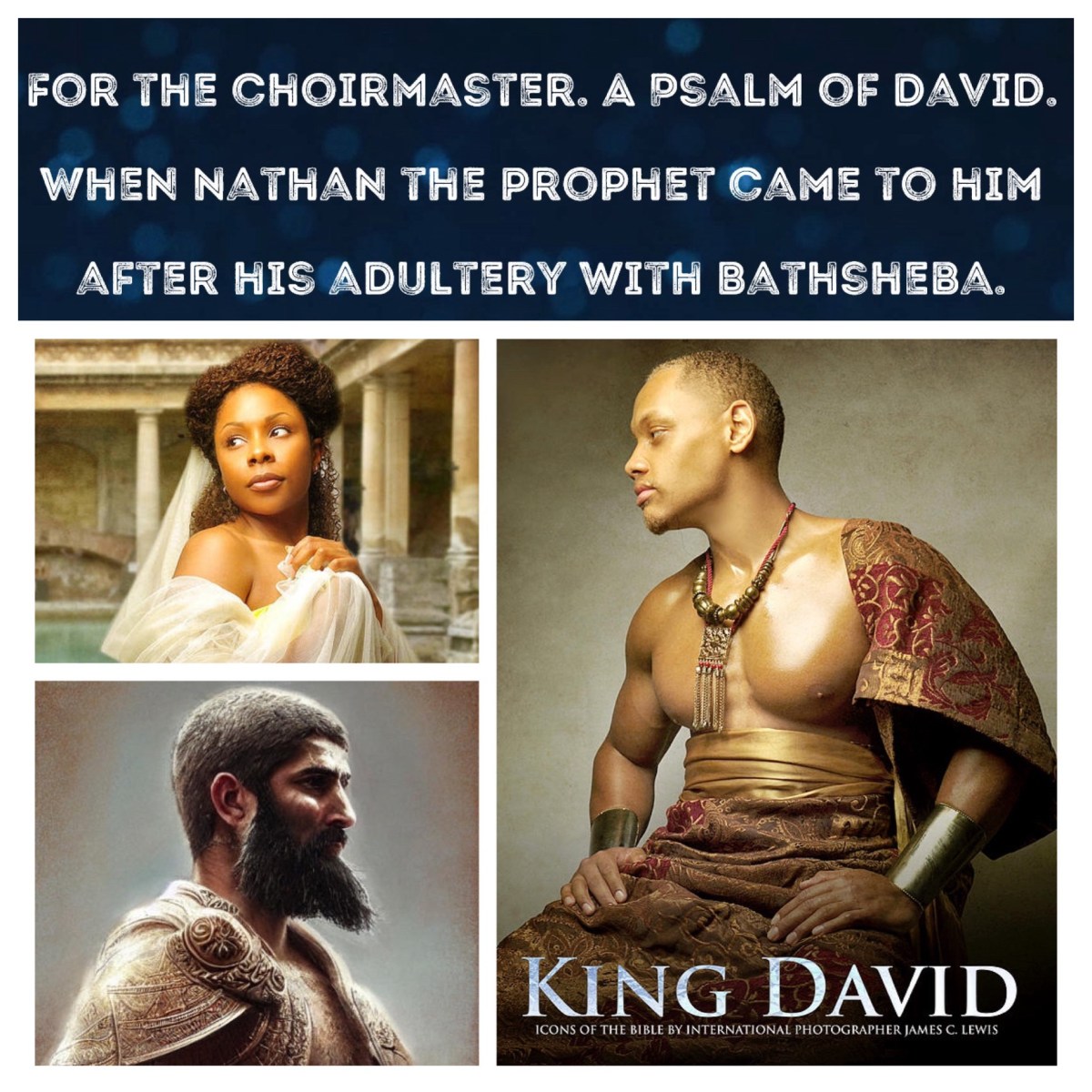

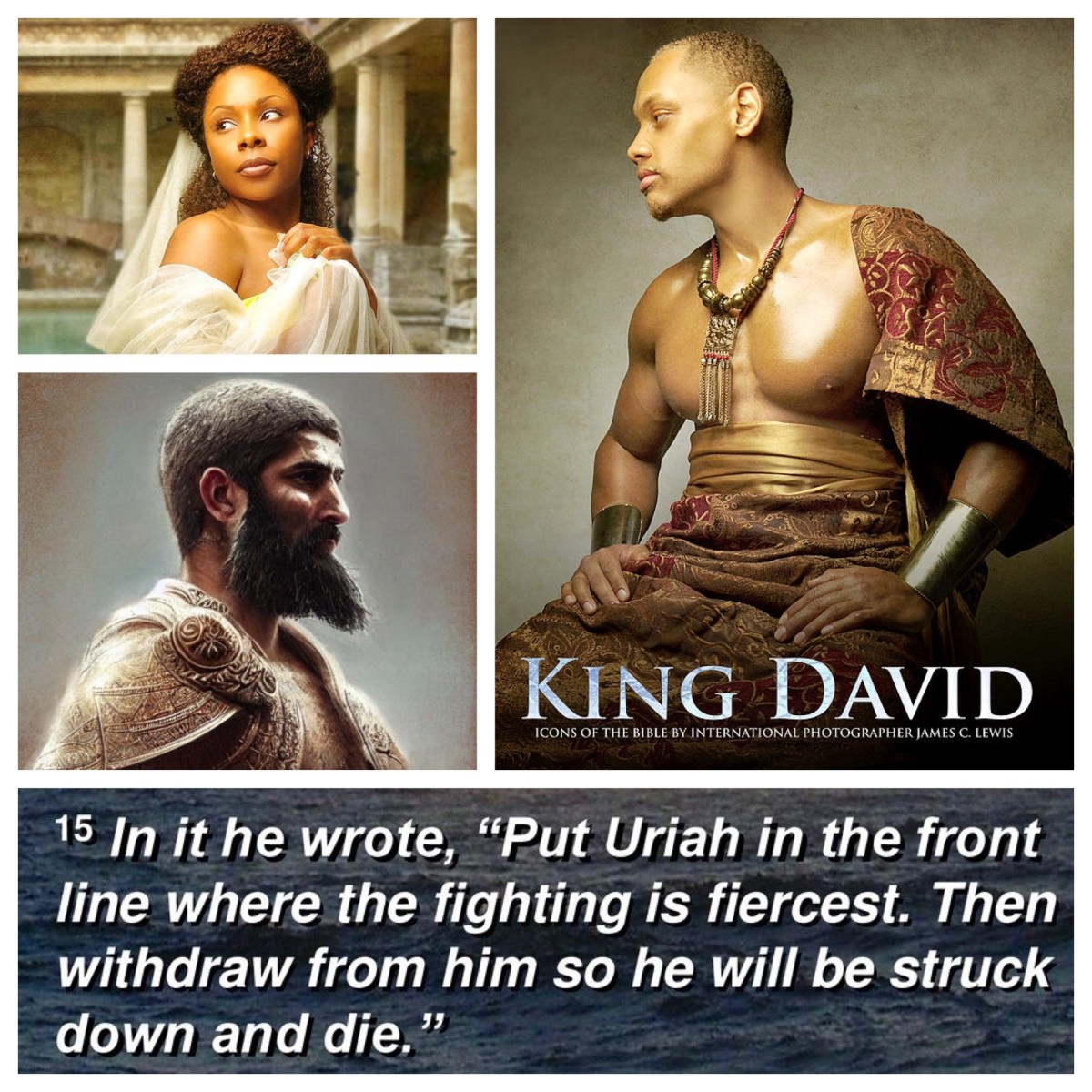

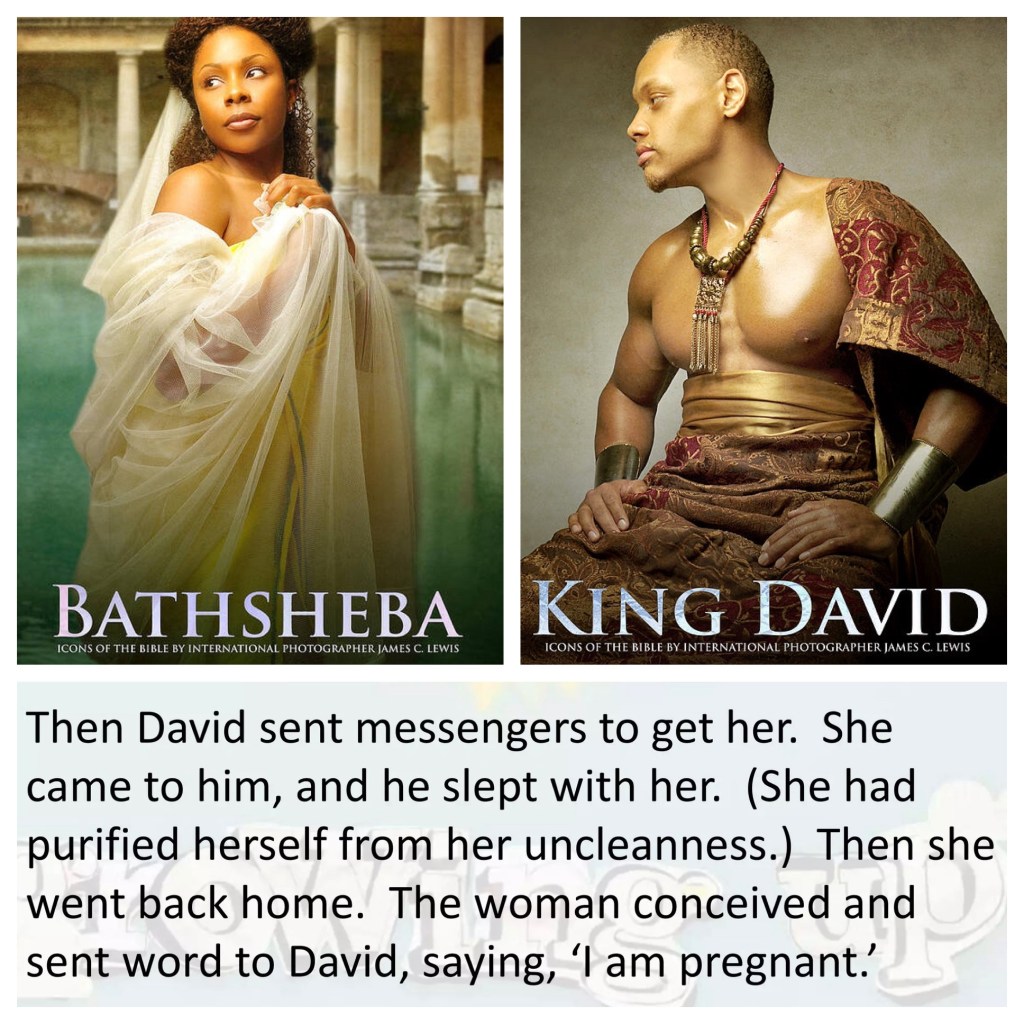

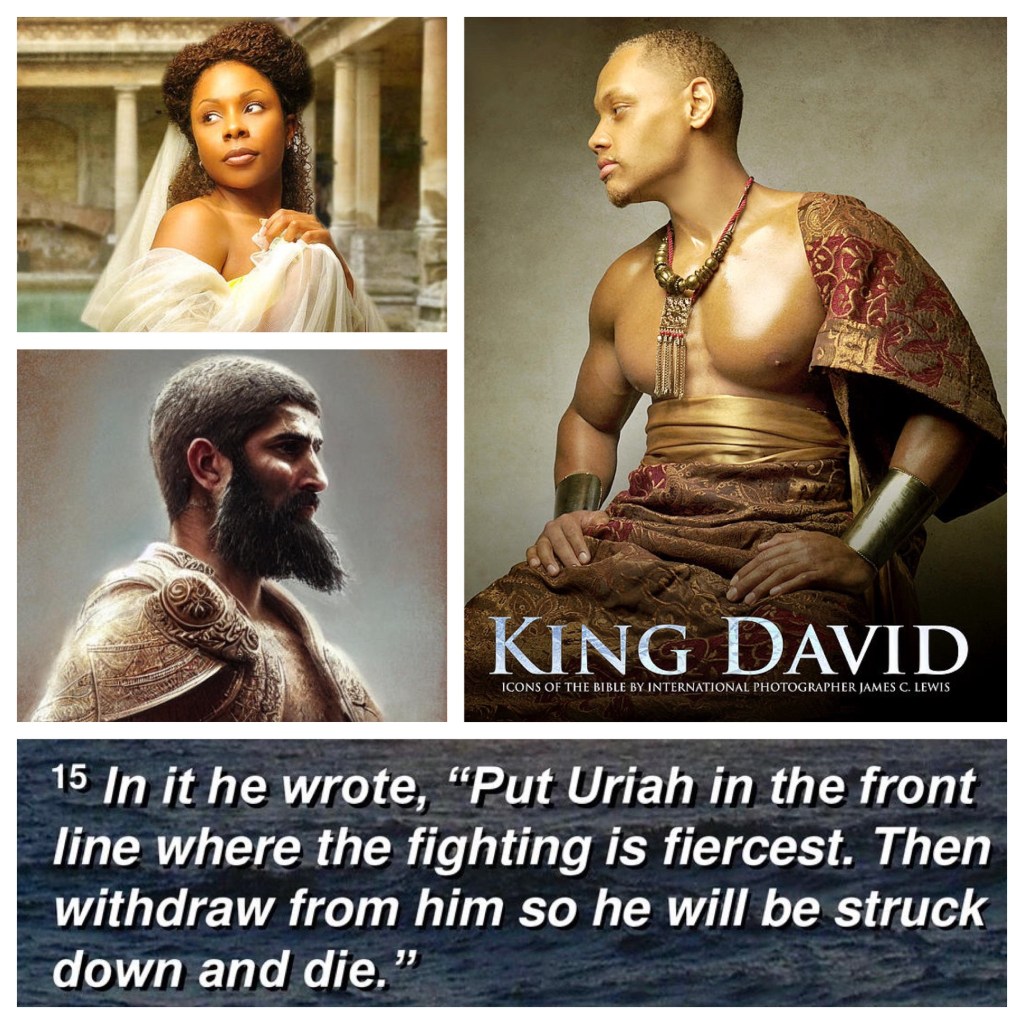

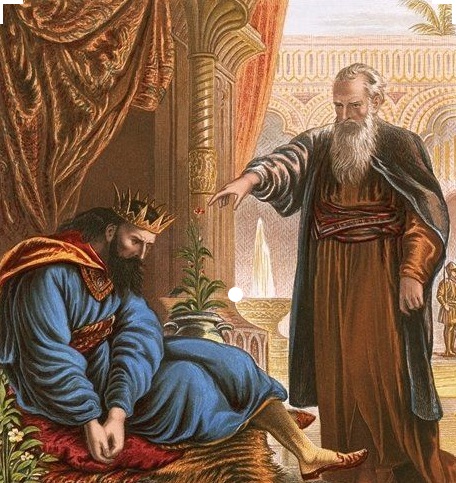

We have seen how he took one of the last remaining strongholds, held by the Jebusites, to make his new capital, in Jerusalem, the ironically-named “city of peace” (2 Sam 5), and how he reactivated the role of the Ark of the Covenant (2 Sam 6). Then we have heard the commitment that the Lord God made to David, that “your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me; your throne shall be established forever” (2 Sam 7). Finally, we have watched in horror as the king has raped Bathsheba and ordered the murder of her husband, Uriah (2 Sam 11), and been confronted about his sin by the prophet Nathan (2 Sam 12).

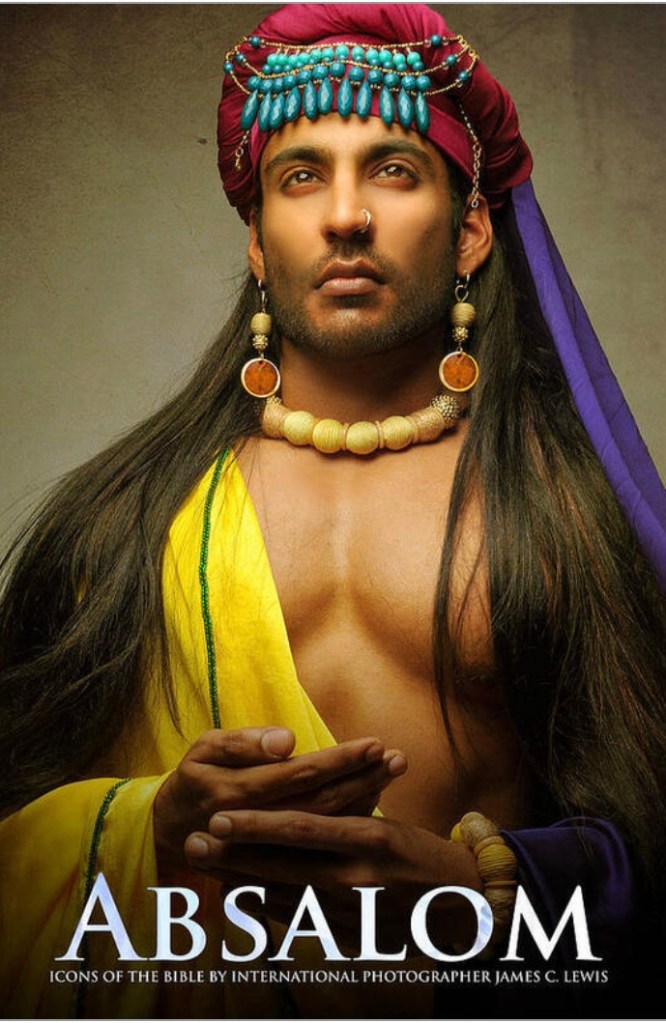

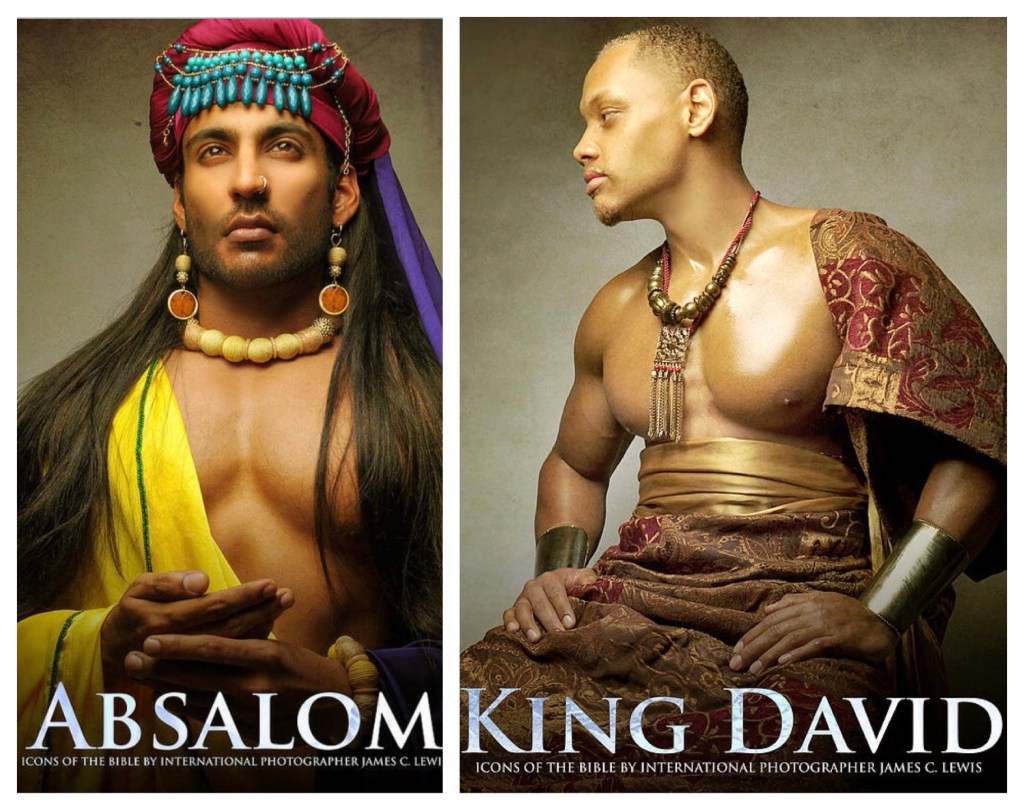

We have jumped over a number of other incidents that have not featured in the selections offered by the lectionary, and particularly some involving Absalom. David’s third son Absalom receives some great press in the narrative of 2 Samuel. For a start, his name means “the father of peace”; that sounds great, but the reality of his life was quite different.

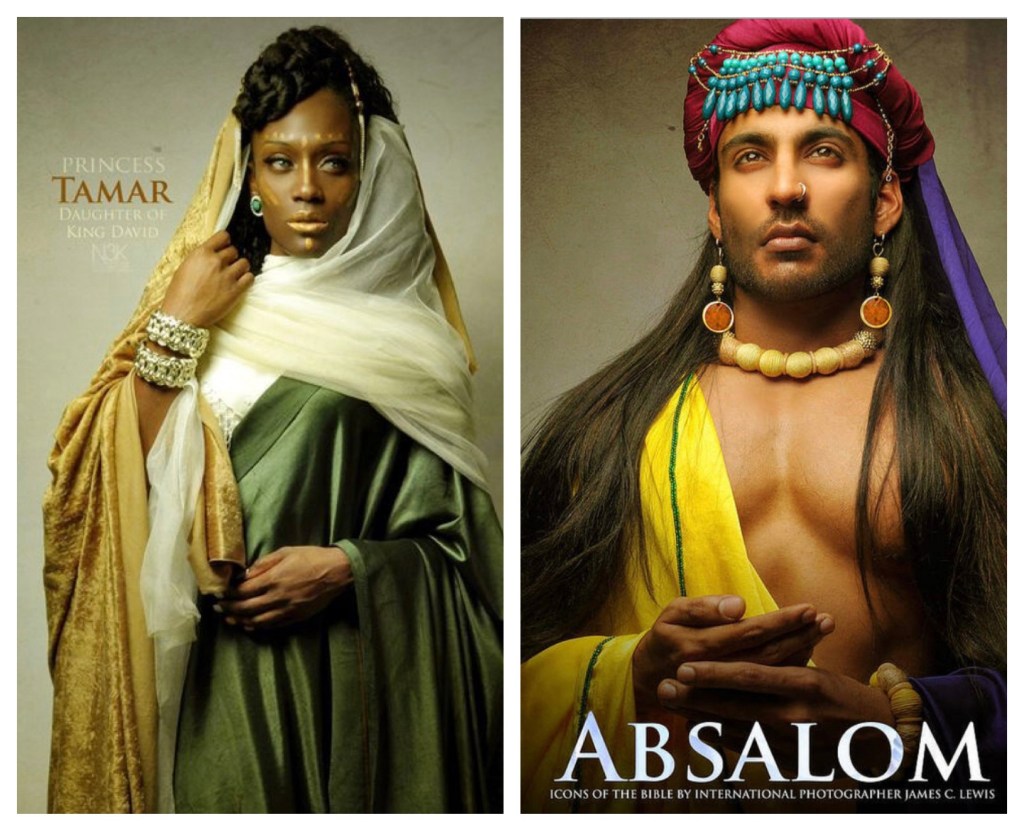

Then, it was claimed that “in all Israel there was no one to be praised so much for his beauty as Absalom; from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head there was no blemish in him” (14:25). From what is told about him in the surrounding chapters, however, both his name and this description seem quite incongruent.

We initially meet Absalom in the list of David’s earliest children: “Sons were born to David at Hebron: his firstborn was Amnon, of Ahinoam of Jezreel; his second, Chileab, of Abigail the widow of Nabal of Carmel; the third, Absalom son of Maacah, daughter of King Talmai of Geshur; the fourth, Adonijah son of Haggith; the fifth, Shephatiah son of Abital; and the sixth, Ithream, of David’s wife Eglah. These were born to David in Hebron” (2 Sam 3:2–5).

Absalom appears in a number of incidents from 2 Sam 13 until his death in 2 Sam 18. The first incident (13:1–39) is a most unsavoury matter involving his siblings, Amnon and Tamar. Amnon fell in love with Tamar, a virgin (13:1–2), and conspired to be alone with her.

When this eventuates, Amnon “took hold of her, and said to her, ‘Come, lie with me, my sister’”; but she refused, responding “do not force me … such a thing is not done in Israel; do not do anything so vile!” ( 13:11–13).

The account of this scene, when Amnon rapes Tamar, is detailed—unlike the brief (one-verse) noting of the rape perpetrated by their father, David, at 11:4. See

Amnon has committed a sin, and he needs to be brought to account. He treats his sister savagely; “being stronger than she, he forced her and lay with her” (13:14), and then, “he called the young man who served him and said, “Put this woman out of my presence, and bolt the door after her” (13:17).

The parallels with David—lying with Bathsheba to rape her, and then ordering the murder of Uriah—are striking. Has Amnon taken on the burden of shameful behaviour that the narrator was reticent to place directly on David? The story reads, to me, as a case of “like father, like son”. Or is the punishment due to David for his double sin being placed on Amnon?

Absalom was horrified when he learnt what had happened; he did nothing, although the omniscient narrator apparently sees into his heart: “Absalom hated Amnon, because he had raped his sister Tamar” (13:22).

Eventually, after two years, Absalom arranged for his rapist brother to be killed, and his servants duly obeyed (13:28–29). David, the rapist father, was enraged (13:33); he is evidently unaware that he had earlier done just this thing to the innocent Uriah!

So Absalom fled (13:34, repeated at 13:37). David sent for him (14:21) but when he came back to Jerusalem, “he went to his own house and did not come into the king’s presence” (14:24). After a further two years, Absalom eventually “came to the king and prostrated himself with his face to the ground” (14:33)—a sign of his complete submission to the king.

However, this cannot have been what was actually in his heart; the narrator informs us that he rebelled against his father and “stole the hearts of the people of Israel” (15:6). After four years of working his way into the favour of the people, Absalom declared himself king, forcing David to leave Jerusalem for a time (15:7–12). David fled into exile (15:13–18), crossing the Wadi Kidron, heading out “toward the wilderness” (15:23).

What follows in the next few chapters is a series of machinations, as the king-in-exile plotted his return to Jerusalem; eventually his forces routed the usurper (18:6–8). It is yet another murky period in Israel’s history. David had wanted Absalom spared, but Joab ordered him to be killed (18:14–15). David’s reign was secured, but his heart was broken; “would I had died instead of you”, he laments (18:33).

This final verse exposes once again the complexity of David; at once grasping to hold on to power, yet grieving for his lost son (19:1–2). Absalom, the “father of peace”, has not bequeathed any peace to his own father, David. They are both complicit in this tragic end.

The lectionary has offered us just isolated excerpts from the final chapter in this longer saga, proposing that we read and hear only 2 Sam 18:5–9, 15, 31–33. Writing in With Love to the World, Matthew Wilson reflects on the whole story. “If you, like me, read the missing bits of the lectionary when it skips verses, you will find a story far more complex and nuanced that a casual reading of the verses provides. I see a father who both loves his son, and wants his throne back.”

Wilson muses on the questions raised by the story: “How do we respond when our power is threatened? What happens when the young and the restless seek their time in the sun and their chance to make decisions?Despite David’s best intentions and desires to ensure Absolom’s safety, such battles for power do not end well for all those involved.”

He continues, “Yet in all that occurs, God finds a way, through tragedy, human greed, and ambition, to continue to build a relationship with the people of Israel, and keep God’s promises to David. Sometimes we just have to trust God.”

As a closing note: it is interesting that the Chronicler barely mentions Absalom—his name appears only in the list of wives and concubines of Rehoboam, the grandson of David who became the first king of Judah after the death of Solomon led to the split of the united kingdom (2 Chron 11:18–21).

In like manner, the story of David and Bathsheba is completely missing from the writings of the Chronicler, and the description of David “dancing before the Lord” (2 Sam 6:5, 15) is modified to be less explicit (1 Chron 15:29). The ragged edges of David’s character do not survive this later retelling!

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.

You can subscribe on your phone or iPad via an App, for a subscription of $28 per year. Search for With Love to the World on the App Store, or UCA—With Love to the World on Google Play. For the hard copy resource, for just $28 for a year’s subscription, email Trevor at wlwuca@bigpond.com or phone +61 (2) 9747-1369.