In the Uniting Church’s resource provided for worship leaders, Uniting in Worship, there is a Calendar of Commemorations, based on the cycle of annual feast days for saints in the Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox churches—but broadened out to be much wider than this. Many days of the year are designated to remember specific people. Today (25 April) is the day allocated to remember John Mark, fellow worker with Paul and, by tradition, the author of the earliest Gospel.

Mark, it is believed, was a young man at the time of Jesus. The first explicit mention of this young man comes in Luke’s description of the community of believers, gathered together. When Peter was released from prison, he went to “the house of Mary, the mother of John whose other name was Mark, where many had gathered and were praying” (Acts 12:12).

It’s interesting to wonder whether this gathering in the house of this Mary might have been in the same place, with many of the same people, who gathered in Jerusalem, after the resurrection and ascension of Jesus, but before the Day of Pentecost. That gathering was in “the room upstairs where they were staying”, without the owner of the house being noted. Included in the people participating in this gathering was “Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers” (Acts 1:12–14). John Mark is not mentioned amongst those named in this group on that earlier occasion.

John Mark is mentioned further time in Acts after the gathering in Jerusalem in Acts 12. After working for a year in Antioch (11:26), Barnabas and Saul “returned to Jerusalem and brought with them John, whose other name was Mark” (12:25). It seems that John Mark had been sharing in ministry with Barnabas and Saul in Antioch.

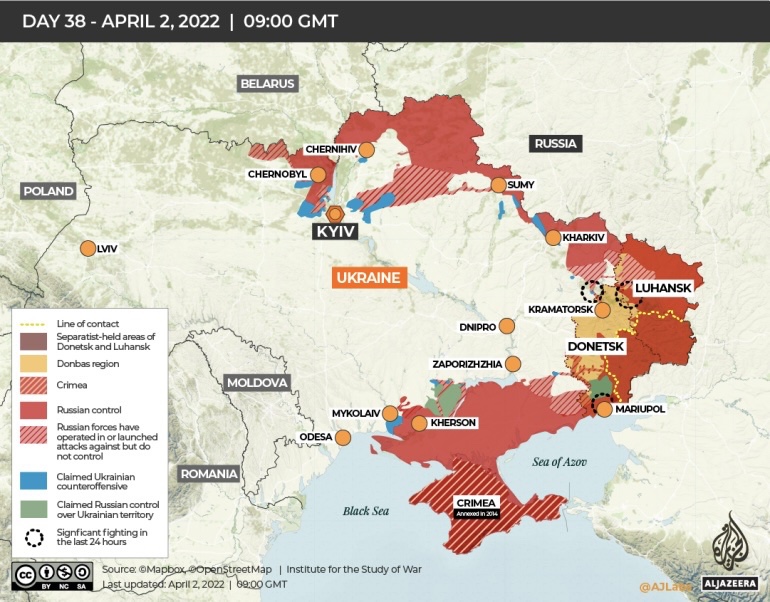

The final reference to John Mark occurs at a critical moment in the narrative about the mission that Barnabas and Saul had been undertaking. They had spent time in Antioch in Syria (11:22–30), Cyprus (13:4–12), Antioch in Pisidia (13:13–52), Iconium (14:1–5), Lystra and Derbe (14:6–20), Barnabas and Saul travelled back to Antioch in Pisidia (14:21–23) and then on back to Antioch in Syria (14:24–28).

After a council of the church was held in Jerusalem (15:1–29) and a report from that was given in Antioch (15:30–35), there was some discussion about revisiting “the believers in every city where we proclaimed the word of the Lord and see how they are doing” (15:36).

Luke reports that “Barnabas wanted to take with them John called Mark. But Paul decided not to take with them one who had deserted them in Pamphylia and had not accompanied them in the work” (15:37–38). This earlier desertion of the apostles—not actually noted in the text at the time it was said to have taken place—was the basis for Paul’s opposition to this proposal.

Luke indicates that “the disagreement became so sharp that they parted company”; the word that is used here, paroxysmos, is sharp and cutting (we derive the word paroxysm from it). So “Barnabas took Mark with him and sailed away to Cyprus; but Paul chose Silas and set out, the believers commending him to the grace of the Lord (15:39–40). Silas would be the ongoing companion of Paul for some time thence.

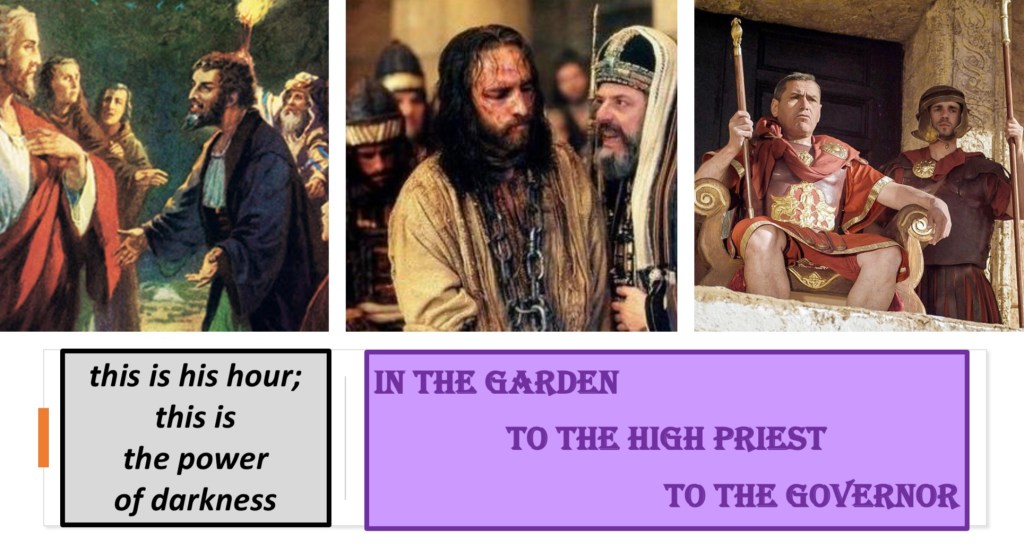

There is an ancient church tradition, however, that identifies John Mark with “a certain young man”, not named in the text, who was “wearing nothing but a linen cloth” (Mark 14:51). This young man, perceived to be one of the followers of Jesus, was with Jesus in the garden at the critical time when, as the Gospel reports, all those who were with him “deserted and fled” (14:50). The text explicitly notes of this “certain young man” that the “crowd with swords and clubs, from the chief priests, the scribes and the elders” (14:43) caught hold of him as the others fled, “but he left the linen cloth and ran off naked” (14:52).

This young man—the first Christian streaker!—has been identified as John Mark, and it’s further claimed that he was the author of the work we know as the Gospel according to Mark. The “evidence” in the text is as clear as the clothing that the young man was wearing—it slips away in an instant, it is nothing of any substance at all.

What else do we know of John Mark? Is he the “Mark, cousin of Barnabas” mentioned at Col 4:10? His name appears here and in Philemon 24, amidst a similar cluster of men identified as fellow-workers of Paul (Epaphras, Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke; see Col 4:10–14). The names of three of these men (Mark, Delmas, and Luke) recur amidst the people noted at 2 Tim 4:9–11; also named are Crescens, Titus, Alexander, and Tychicus).

This section of 2 Tim may well be an historical fragment from the time of Paul, inserted into a letter written at a later time, claiming Pauline authorship (but betraying many signs of a later composition). But nothing definitively links this Mark with the John Mark of Acts (nor, for that matter, with the author of the earliest extant Gospel).

The later relationship between John Mark and Paul is also hinted at in a further letter, attributed to Peter (but most likely not authored by either him), which concludes with a note that Silvanus (whom some think may have been Silas) assisted in writing the letter, and that “my son Mark sends greetings” (1 Pet 5:12–13).

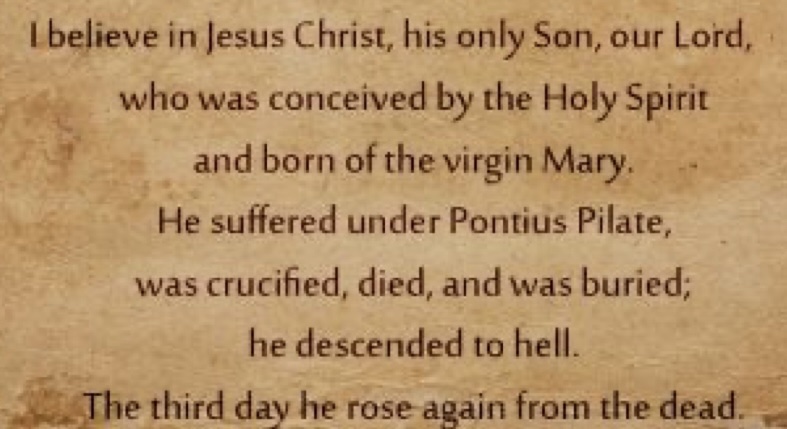

This verse has contributed to the tradition that Mark was a disciple of Peter (the word translated “son” could also infer he was a “disciple”)—and thus, that Mark’s Gospel came from when Mark, “in his capacity as Peter’s interpreter, wrote down accurately as many things as he recalled from memory—though not in an ordered form—of the things either said or done by the Lord”, as Papias declared (Eusebius, Church History 3.39). The lion is the symbol that is traditionally attached to this Gospel.

But this claim about authorship comes from a later century, and is not an observation made at the time the Gospel was written. See

The closing words of the letter attributed to Peter are a fitting conclusion to our consideration of the mercurial John Mark: “Greet one another with a kiss of love. Peace to all of you who are in Christ.” (1 Pet 5:14). If he was, indeed, with Peter, and if this was, indeed, their wish for “the exiles of the Dispersion in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia” (1 Pet 1:1), it stands as a fine testimony from this first century follower of Jesus.

Mark is subsequently credited as being the founder of the church in Egypt. The Coptic Church (the Church of Alexandria) is called the “See of St. Mark”; it is claimed as one of the four earliest sees: Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, and Rome. John Mark regarded in the Coptic Church as the first of their unbroken 117 patriarchs, and also the first of a stream of Egyptian martyrs.

An apocryphal story told about John Mark concerns an incident soon after he had left Jerusalem and arrived in Alexandria. On his arrival, the strap of his sandal was loose. He went to a cobbler to mend it. When the cobbler, named Anianos, took an awl to work on it, he accidentally pierced his hand and cried aloud “O One God”. At this utterance, it is said that Mark miraculously healed the man’s wound. This gave him courage to preach to Anianos. The spark was ignited and Anianos took the Apostle home with him. He and his family were baptized, and many others followed.

It is said that John Mark went to Rome, but left there after Peter and Paul had been martyred; he then returned to Alexandria and was martyred there in the year 68, after an altercation with a crowd attempting to celebrate the feast of Serapis at the same time as the Christians were celebrating Easter.