John’s Gospel, it is often said, is the place to go in the New Testament if you want to find “proof texts” in support of antisemitism. In this Gospel, “the Jews” are labelled as children of the devil, accused of rejecting the belief that Jesus is God, tarred with the claim that they plotted against Jesus, and blamed with bringing about his death.

However, the passage that is providing the basis for the lectionary Gospel at this time of the year (John 6, Pentecost 9B—13B) does not feed into this negative perspective about “the Jews”. As we read it carefully, we see a different relationship unfolding between the Jew Jesus, his Jewish followers, and the crowd of Jews that interact with him throughout the chapter.

(And let me be clear—I am neither advocating antisemitism nor tarring John’s Gospel as being unredeemingly antisemitic.)

Whilst the terrible claim that “the Jews killed God” was not uttered until some centuries later—from the lips of John “the golden-mouthed”, Bishop of Antioch, in one of his Homilies Against the Jews—there is enough within the way that the author of the book of signs tells the story to apparently vindicate the claim that “the Jews killed Jesus”—at least in the eyes of many interpreters throughout Christian history.

1 Jewish opposition to Jesus

Jewish opposition to the message and activities of Jesus is evident from early in the book of signs. Jesus has identified himself with “the Jews” in his conversation with the woman by the well in Samaria (4:19–22).

However, he becomes caught in a dispute with “the Jews” while he was in Jerusalem, before travelling to the Sea of Galilee (6:1) and then to Capernaum (6:17). This dispute arose because these Jews in Jerusalem interpreted Jesus’ healing of the lame man on a Sabbath as being a breach of Torah (5:10). They seek to kill him, accusing him of making a blasphemous claim (5:18).

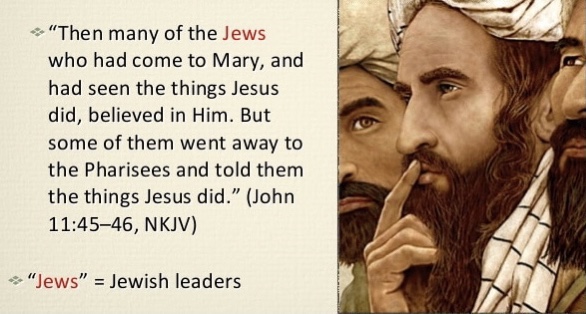

A footnote for verse 10 in my electronic copy of the NRSV helpfully clarifies that “the Greek word Ioudaioi refers specifically here to Jewish religious leaders, and others under their influence, who opposed Jesus in that time; also verses 15, 16, 18”. We will return to that notion later.

Jesus disputes the interpretation of the crowd, claiming that by healing on the Sabbath he continues to do “the works which the Father has granted me” (5:36). This is language which recurs in the conversation that takes place in chapter 6, where a crowd of Jews in Capernaum enquire of Jesus, “what must we do, to be doing the works of God?” (6:29).

Dissension continues to haunt Jesus, however; once he is back in Jerusalem, the crowd accuses him of having a demon (7:20; 10:20). This is later repeated by “the Jews” in Jerusalem at 8:48–52, and again at 10:20, with the added insult that he is a Samaritan (8:48). A third criticism levelled against Jesus is the inference that he was born illegitimate (8:41).

The words of “the Jews” represent a tense argument which was taking place within the Judaism of the first century, as Jewish followers of Jesus debated with the authorities in their synagogues about the status of Jesus of Nazareth. Indeed, Jesus later predicts that his fate will set the pattern for the fate of his followers; “if they persecuted me, they will persecute you also” (15:20). The tensions within Judaism are clearly reflected in references to followers of Jesus being excluded from the synagogue (9:22; 12:42: 16:2–3).

It is true that “the Jews” of Jerusalem prepared to stone Jesus twice (first at 8:59, again at 10:31). This seems to validate the claim made earlier by Jesus, that his fate is to be hated by the world (7:7); as well as the prediction in the Prologue pointing to the rejection of the Word (1:10–11).

2 The role of Jewish leadership

It is not, however, “the Jews” as a whole who plot to arrest Jesus. It was the chief priests who first made plans to put Lazarus to death (12:10), just six days after those same priests had conspired with the Pharisees, making plans to arrest Jesus so they could put him to death (11:47–53). The text makes it clear that this was done despite the fact that “many of the Jews who had come with Mary and had seen what he did [in raising Lazarus] believed in him” (11:45).

It was clearly the leadership of the Jews involved in the plotting against Jesus. Was it not likely, then, that the same group had been conspiring throughout the whole story, planning his demise? That is clearly what is intended in the earlier account we attribute to Mark, which notes early in the Gospel that, immediately after a healing by Jesus, “the Pharisees went out and … held counsel with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him” (Mark 3:6).

We read that “a band of soldiers and some officers from the chief priests and the Pharisees” come to seize Jesus in the garden (18:3). When Jesus appears before Pilate, the governor notes, “your own nation and the chief priests have delivered you over to me” (18:35). When Jesus is sent out of the governor’s praetorium, it is “the chief priests and the officers” who cry out, “Crucify him, crucify him!” (19:6a).

This leads to Pilate saying to them, “Take him yourselves and crucify him, for I find no guilt in him” (19:6b). This is one of the key texts that shifts the blame for the death of Jesus from Roman to Jewish leadership—a factor that is included in all four canonical Gospels (Mark 15:6–14; Matt 27:11–26; Luke 23:4, 13–14, 18–25; John 19:12–16).

The Passion Narrative in John’s Gospel continues to press the blame for the crucifixion of Jesus directly onto the chief priests. When Pilate asks, “shall I crucify your King?”, the chief priests answer, “We have no king but Caesar” (19:15). When Pilate orders an inscription to be prepared for Jesus, the chief priests say to Pilate, “Do not write, ‘The King of the Jews,’ but rather, ‘This man said, I am King of the Jews’” (19:21).

Both of these incidents appear to be quite implausible historically, given what we know of Jewish nationalism under Roman rule. Likewise, the scene where the Jewish crowd bays for the blood of Jesus rather than Barabbas could not have occurred—there is no evidence for the release of a prisoner at Passover, as the Gospels suggest.

These factors underline the strong likelihood that the author of the book of signs—along with the other authors of the Synoptic Gospels—has placed more of the blame for the death of Jesus onto the shoulders of the Jewish authorities, rather than the Romans. The charge of antisemitism in these Gospels needs to be considered and dealt with.

3 “The Jews” in John 6

Nevertheless, a more careful reading of the book of signs as a whole points to a more nuanced understanding, one that makes space for sympathetic readings of the role of “the Jews” in this document. We have already noted the important distinction between “the Jews” as a whole, and specific Jewish leadership in Jerusalem.

The passage that provides the basis for the lectionary Gospel at this time of the year (John 6) pushes us in this more nuanced interpretive direction. In this story, Jesus and the disciples—who, let us remember, were all Jews—are engaged with a large crowd—who also were Jews, as the scene is clearly set in Jewish territory near Capernaum (6:24).

The interaction between Jesus and the crowd begins “when the crowd saw that Jesus was not there, nor his disciples, they themselves got into the boats and went to Capernaum, seeking Jesus” (6:24). In the scene that plays out over the ensuing fifteen verses, the crowd of “the Jews” behave, in my view, quite responsibly and respectfully towards Jesus. They are seeking him—looking to engage further with him, be with him, learn from him.

The first interaction comes “when they found him on the other side of the sea, they said to him, ‘Rabbi, when did you come here?’” (6:25). This is a genuine enquiry, which evokes an explanation from Jesus. It’s a straightforward conversation, with no hidden agendas at play.

The crowd then said to Jesus, “What must we do, to be doing the works of God?” (6:29). This, too, is simply an enquiry soliciting information. “Doing the works of God” references a standard biblical phrase. It usually describes the work that God did in bringing the whole creation into being (Heb 4:4; see Job 37:14; 40:19; Ps 73:28), although in Psalm 78, “not forgetting the works of God” (78:7) is set into the context of teaching the law and keeping the commandments (78:5–8).

Could the Jewish crowd in Capernaum be asking Jesus about how they might join with him in living as co—creators with God, in harmony with the created order, in obedience to the covenant promises they have made, through keeping the commandments of the Law?

In true Johannine style, however, Jesus in this story reduces the whole covenant relationship to one simple factor: “this is the work of God, that you believe in him whom he has sent” (6:29), to which they reply, “Then what sign do you do, that we may see and believe you? What work do you perform? Our fathers ate the manna in the wilderness; as it is written, He gave them bread from heaven to eat.’” (6:30-31).

The interaction taking place here is not antagonistic or accusatory. The crowd is pressing Jesus on what they have seen, and exploring what he meant to do when he fed the crowd, as reported earlier in the chapter. The crowd refers to scripture to interpret their experience; this was a normal part of Jewish discipleship. They know very well the story about Moses leading the people of Israel through the wilderness, and the provision of manna from heaven for them to eat (Exod 16:27–36; Num 11:4–9).

The response from Jesus provides an explanation to the crowd in terms of the scripture story to which they have referred—the manna given to Israel in the wilderness (6:32–33). That was a gift, not from Moses, but from God.

The crowd responds to the teaching of Jesus in a way that is enquiring and appreciative. They do not respond in anger, or in disagreement, or with a mocking tone. They simply say to Jesus, “Sir, give us this bread always” (6:34). The crowd remains open to what Jesus is teaching, keen to learn more of what he speaks, engaged with the lesson that Jesus is providing. This crowd of Jews is not at all like the groups who “seek all the more to kill him” (5:18), who press Jesus antagonistically (7:20; 8:48–52; 10:20).

Of course, we as the readers can see how the author of this Gospel is, typically, running a narrative at two levels—the surface level of discussion about bread, and the deeper level of discussion pointing to “the living bread which came down from heaven”. But this is typical Johannine style. There is nothing negative to be said about the crowd to this point. The explanation from Jesus, “I am the bread of life; whoever comes to me shall not hunger, and whoever believes in me shall never thirst” (6:35), then draws together both the levels at which the narrative has been running.

4 Questioning Jesus about “bread from heaven”

From this point on, the interaction becomes more complex. First, we read that “the Jews grumbled about him, because he said, ‘I am the bread that came down from heaven’” (6:41). The reference to the Jews “grumbling” also evokes the wilderness stories from Jewish tradition. The people of Israel grumbled against Moses (Exod 15:24; 17:3) or against Moses and Aaron (Exod 16:2; Num 14:2, 29; 16:41), resenting their leadership when things became tough for them as they continued their way through the wilderness. They had no water, no food, no comfort, in their wilderness wanderings.

The grumbling of the people in this scene, however, does not relate to lack of provisions—after all, the crowd had earlier been fed with abundance (John 6:5–13). The crowd focuses on the identity of Jesus. The crowd said, “Is not this Jesus, the son of Joseph, whose father and mother we know? How does he now say, ‘I have come down from heaven’?” (6:42). Jesus is described as “son of Joseph” only in the book of signs (1:45, and here). Luke introduces him as “the son (as was supposed) of Joseph” (Luke 3:23), whilst Mark identifies him as “the son of Mary” (Mark 6:3), and Matthew has the crowd in Nazareth asking, “is not this the carpenter’s son? is not his mother called Mary?” (Matt 13:55).

Whatever was thought about the parentage of Jesus, the question of the crowd here has to do with the contrast between his earthly and heavenly origins. Jesus was known to his contemporaries, quite understandably, through his family of origin; claims about his heavenly origin sit uncomfortably with this understanding.

Yet for the author of the Gospel, the heavenly origins of Jesus are indisputable: “you are from below, I am from above”, he later tells the crowd (8:23; see also 3:31). The people in the story act as we might reasonably expect; the people outside the story, hearing it from the perspective of the narrator, know of the deeper level of meaning that is so typical of the Johannine narrative.

The answer provided by Jesus reinforces his central claim, “I am the bread of life” (6:48), “I am the living bread” (6:51), and extends it by noting “this is the bread that comes down from heaven” (6:50). Belief in this leads to eternal life—a claim that is a regular refrain in this Gospel (6:47; see also 3:15, 16, 36; 4:14, 36; 5:24; 6:27, 40, 54, 60; 10:28; 12:25, 50; 17:2–3). And, more shockingly, Jesus ends this section with the word that will provoke, at long last, a dispute amongst “the Jews” listening to him.

The Greek word translated as “dispute” is schisma, from which we get schism and schismatic. The same dynamic of division is reported amongst the Pharisees when confronted with the healing of the man born blind (9:16) and again amongst the crowd in Jerusalem as they hear Jesus teaching that he is “the good shepherd” who has authority from the Father (10:19). The response is a typical pattern amongst those who listen intently to the teachings of Jesus.

Jesus concludes with another short burst of teaching which presses the final point of the last section into an even harder claim. The bread Jesus gives is his flesh. He sharpens the point, however, by referring directly to the eating of his flesh and the drinking of his blood—actions utterly anathema to faithful Jews. It is as if the author is deliberately placing Jesus in dangle of total rejection by the crowd.

Jesus concludes by reasserting his earlier polemic, “This is the bread that came down from heaven, not like the bread the fathers ate, and died. Whoever feeds on this bread will live forever” (6:58). He will not step back from the dissension he has produced.

5 The response of the disciples

The last section of the chapter provides a most intriguing resolution to the narrative. The immediate response of “many of his disciples” is sharp: “this is a hard saying; who can listen to it?” (6:60). It is not the crowd that responds in this way; it is a group within the disciples that react.

It is interesting that, at this point, the narrator observes that “many of his disciples turned back and no longer walked with him” (6:66). If anyone is to be seen as the opposition in this chapter, the ones turning their back on Jesus, it is surely this group of “many of his disciples”. We rarely hear about the failures of Jesus. This chapter reports a clear instance. Not every disciple of Jesus stuck with him all the way.

In fact, Jesus reassess the point, saying to the twelve, “Do you want to go away as well?” (6:67). Apart from the description of Thomas as “one of the twelve” (20:24), this is the only place in this Gospel where the inner group of twelve disciples is explicitly identified (6:70, 71). Jesus takes the key issue right to the heart of his followers.

The answer of Simon Peter is noteworthy. “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life, and we have believed, and have come to know, that you are the Holy One of God.” (6:68-69).

This is a climactic moment, a high point of confession of the true identity of Jesus. It evokes the Caesarea Philippi confession of Peter in the Synoptics (Mark 8:29; Matt 16:16; Luke 9:20)—although in the book of origins, it is actually Martha, not one of the male disciples, who mirrors this confession as she makes the ultimate confession, “you are the Christ, the Son of God” (11:27).

Jesus presses the point with his disciples, seeking to make sure that they are, indeed, committed to continue following him. “Did I not choose you, the twelve?” he asks, continuing, “yet one of you is a devil” (6:70). Another “hard saying” from Jesus, for his followers to hear.

The narrator then explains, “he spoke of Judas the son of Simon Iscariot, for he, one of the twelve, was going to betray him” (6:71). At precisely the moment when the remaining disciples seem to be firmly committed to their following of Jesus, he punctures their assurance, demonising one of their number with these incisive words. Even this group of faithful followers will be fractured.

See also https://johntsquires.com/2021/08/02/claims-about-the-christ-affirming-the-centrality-of-jesus-john-6-pentecost-9b-13b/ and https://johntsquires.com/2021/07/20/misunderstanding-jesus-they-came-to-make-him-a-king-john-6-pentecost-9b/