The passage from Acts which is offered by the lectionary this coming Sunday (Acts 10:34–43) is an impassioned speech to Gentiles, by the Jewish man, Peter. It is one of a number of speeches that are found throughout the first two thirds of the book of Acts, in which one of the leaders in the movement that was initiated by Jesus (and would later become “the church”) spoke to others, declaring “the good news about the kingdom of God and the name of Jesus Christ” (8:12; see also 8:25, 35, 40; 13:32; 14:7, 15, 21; 15:7; 16:10; 17:18; 20:24).

These speeches, of course, all come to us from the pen of one person, the author of this work; although they are, in good speech-writing style, shaped to the particular situation at hand, there is nevertheless a consistency of themes, ideas, and language that runs through the speeches which have what me might call an evangelistic purpose—declaring the good news (the evangel) to those who have not yet heard it. Whether it is Peter, Stephen, Philip, or Paul who is speaking, the message is consistent and focussed on Jesus and how he relates to God’s intention for the people being addressed.

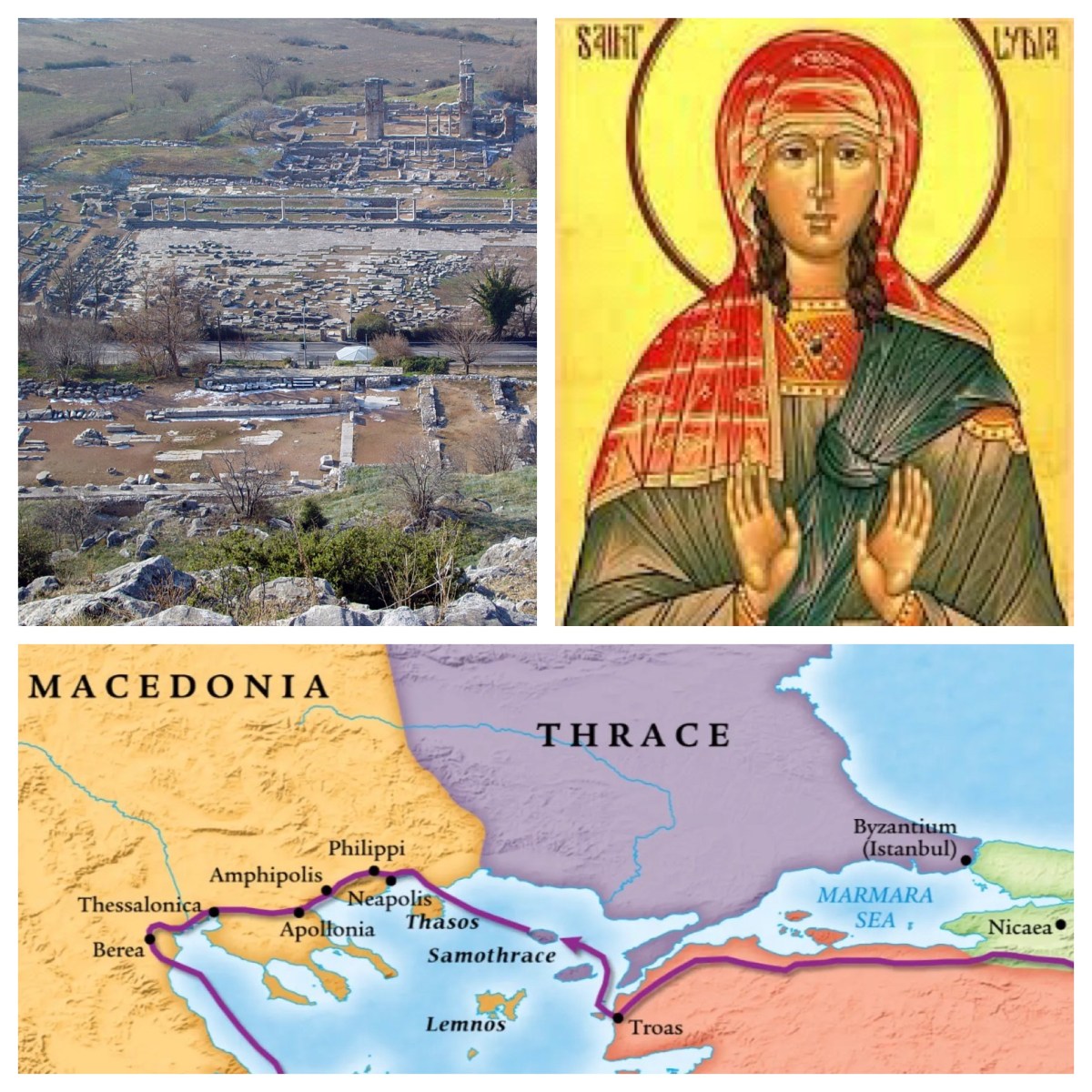

So Peter has come, by a sequence of events that Luke wants us to understand were quite miraculous, from Joppa to Caesarea; from the house of the Jewish man Simon, a tanner, with whom he was staying in Joppa (9:43), to the house of Cornelius, a centurion—and thus most likely a Gentile—in Caesarea (10:1–2). That movement, in itself, is quite significant, as Peter moves from his fellow-Jews to the Gentiles. Cornelius was sympathetic to Judaism; he is described as “a devout man who feared God … who gave alms and payed constantly” (10:2), he was, nevertheless, a Gentile; and those of his household were, likewise, Gentiles.

What Peter says in this speech in the Gentile household of Cornelius needs to be understood in the context of the events that have just taken place, and indeed in terms of the whole span of events recounted in this volume. Peter had been called to Caesarea by a vision, in which God spoke directly to Peter (10:9–15)—and Luke,reports that this took place, not once, but three times (10:16). In what God said, Peter was given a message, to declare to others who were part of the movement that he had been leading since Jesus had ascended into heaven (1:6–14).

That message, “what God has made clean, you must not call profane” (10:15) was, in effect a call to Peter to speak to that movement as a prophet. Prophets were anointed by the spirit to declare “the word of the Lord” for the people of their time (1 Sam 19:20, 23; Isa 11:2; 59:21; 61:1; Ezek 2:2; Joel 2:28–29; Micah 3:8; Zech 7:12, referring to “the former prophets”). Indeed, the servant of the Lord himself is guided by the spirit (Isa 42:1). The Spirit actually calls Peter to go with three men who have come searching for him (10:19–20); they lead him to Caesarea, to the house of Cornelius, where he duly delivers this message (10:24–29).

Subsequently, as he speaks in more details to the assembled household, the Spirit falls on all present, as they listen to Peter’s words (10:44). This coming of the Spirit had happened before, and it will happen again, as the story of Acts continues. But there is something striking and significance about this story of the coming of the spirit.

This has happened before. The spirit has twice filled the messianic community gathered in the Jewish capital, Jerusalem (at Pentecost, 2:1-4, and subsequently, 4:31). When the spirit is poured out on the Gentiles (10:45) in this gentile capital, it is already known that this is an act of God; “God declares, I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams” (2:17).

In both previous cases, God had acted through the spirit in relation to Jews. That this current outpouring of the spirit, outside of Judaea, amongst Gentiles, is still an act of God, is emphasised by a series of narrative comments. The Jewish believers present express surprise at “the gift of the holy spirit” (10:45), but the reader already knows that such a gift is from God (2:38, 8:18).

They hear the Gentiles “speaking in tongues” (10:46), a phenomenon already experienced as a divine event in Jerusalem (2:11). Peter draws this connection when he interprets the event: they “received the spirit as we also [did]” (10:47; see 2:38). Peter and his fellow Jews thus “exulted God” (10:47; see 5:13).

Indeed, the Spirit had come to these Gentiles after a striking sequence of events had taken place. Peter had a vision whilst praying in Joppa, that he was no longer to keep separate at table (10:9–16). No longer were Jews to eat separated from Gentiles. God had declared all foods clean (10:15), so separate table fellowship was now overturned. Peter receives this dramatic change to the status quo—and he faithfully acts on it.

Peter and his companions in Joppa share at table with the men from Cornelius (10:23; 11:4–11) and then, when they have travelled to Caesarea, with the household of Cornelius and those who were baptised with him (10:48; 11:12–18). Indeed, the very point of the vision seen by Peter is to establish an inclusive, all-embracing table fellowship in the Jesus movement, open to both Jews and Gentiles, from this point onwards (11:3).

This is a moment when the old is overturned, and the new is implemented. It is a strong moment of transition for the early church. From this time, the good news spreads amongst Gentiles; to the extent that it does, indeed, reach “to the ends of the earth” (see 1:8) by the end of the book. (In saying this, I take the arrival of Paul into Rome in Ch.28 to be a symbol of the fact that, as the good news becomes known in Rome, the centre of the dominant empire of the day, so that message will then be taken out from the city into all the far-flung reaches of the empire—in a sense, “to the ends of the earth”.)

So the story of Peter and Cornelius, narrated in detail in chapter 10 and then reported in summary to the gathering in Jerusalem in chapter 11, is a key turning point in the overall story being told in Acts. (In my research, I describe Acts 8–12 as “the turn to the Gentiles”, the pivot on which the whole story turns.) it is in this dramatic and pivotal context that Peter speaks the words which are offered by the lectionary for the First Reading on Easter Sunday. This speech is worth attending to in some detail.

*****

This speech by Peter begins in the characteristic style of previous speeches, by announcing God as its subject (see 2:16–21, 22; 3:13; 4:24; 5:29–30; 7:2; and see subsequently at 13:16–17; 14:15–17; 15:7, 13–17; 17:23–25; and as a summary, 20:24, 27). I have explored this in other blogs at

and

The key theme of this speech is the impartiality of God (10:34), an important theme, especially in later scriptural writings. “The Lord your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome, who is not partial and takes no bribe”, Moses declares (Deut 10:17). God is one “who shows no partiality to nobles, nor regards the rich more than the poor—for they are all the work of his hands”, Elihu advises Job (Job 34:19).

Later writings concur: “the Lord of all will not stand in awe of anyone, or show deference to greatness … he takes thought for all alike” (Wisd 6:7), and “do not offer [the Lord] a bribe, for he will not accept it … the Lord is the judge, and with him there is no partiality; he will not show partiality to the poor, but he will listen to the prayer of the one who is wronged; he will not ignore the supplication of the orphan, or the widow when she pours out her complaint” (Sir 35:13–17).

This theme of divine impartiality thus reinforces and confirms the message of the vision (10:11–16). Even though the prescriptions of the levitical holiness code where being adhered to by faithful Jews, the vision speaks over those regulations and invites that who see it and hear God’s words into a new manner of being community. Specifically, that vision validated table-fellowship as being consistent with divine impartiality, a key aspect of God’s nature. Things would be different from now on!

Peter explains that this divine impartiality is especially evident in Jesus, whom he affirms as Lord of all (10:36). Peter interprets the whole life of Jesus as the action of God, who anointed him, was with him, raised him and made him manifest (10:37–43). For Peter, the significance of what Jesus did and said was that he was addressing not only Jews, but also Gentiles.

Peter affirms both the apostolic witness: “we are witnesses to all that he did” (10:39,41; see 2:32, 3:15, 5:32) and also the prophetic witness: “all the prophets testify about him” (10:43; see 2:25-31,33–35, 3:18,21–25, 4:25–26). We see here a rhetorical strategy typical of Luke, who has Peter make the exaggerated claim that “all the prophets testify about him” (10:43; see 3:24). These prophets testify to “the forgiveness of sins” which is essential to this proclamation (2:38, 5:31, 13:38).

Peter continues, that Jesus has been “ordained by God” to be the eschatological “judge of the living and the dead” (10:42), a concept which Paul will later express (17:31; cf. 24:15). The speech thus comprises a consistent exposition of God’s activities in Jesus, extensively in the past as well as (briefly) in the future. When we read what Peter says here, alongside what he says in other evangelistic speeches in Acts (chs. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 13), as well as what Stephen says in his long speech (Ch.7) and what Paul says to Jews (Ch.13) and to Gentiles (chs. 14 and 17), we end up with a most comprehensive statement of the Gospel and how it relates to the ways that God had long been at work in Israel.

The author’s interpretation of the events that have taken place in Caesarea draws them into close relationship with the interpretation of Jesus which Peter has given (here, and in earlier speeches in Acts). That is not surprising, since it is the one person (Luke, the alleged author of this work) who has reported all of these speeches—and, in my opinion, has actually created each speech.

Certainly, the speech itself relates to key features in the surrounding scenes involving Peter, a Jewish man, with the Gentile Cornelius, and his Gentile household. The impartial God who has acted through Jesus (10:34–43) is the same God who declares all things clean (10:15), who shows this to Peter (10:28), who gifts Gentiles by pouring out the spirit (10:45), and who is exulted by the people (10:46). It is language about God which interprets the significance of the narrative at each key moment.

The consequence of this dramatic event is noted briefly: “they invited him to remain for some days” (10:48b). Table-fellowship with Gentiles and the breach of the food rules was considered to be the inevitable result of God’s actions (see also 11:15–18). Such hospitality continues to be one of the key markers of the church today. That is the good news which is declared by the Easter event, when we remember that “God raised Jesus from the dead” and we testify that “everyone who believes in him receives forgiveness of sins through his name”.

*****

In this blog I have developed themes, ideas, and analysis that I wrote in my commentary on Acts in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, ed. Dunn and Rogerson (Eerdmans, 2003). I have also explored the theme of the plan of God throughout Luke and Acts in the doctoral research that I undertook in the 1980s, which was published in 1993 by Cambridge University Press as The plan of God in Luke-Acts (SNTSM 76).