In the Gospel reading provided for Ash Wednesday each year (Matt 6:1–6, 16–21), the lectionary offers us a part of the long discourse that Jesus gave, on top of a mountain, to his disciples (5:1–7:29). The text infers that he was seeking to avoid “the crowds” (5:1), although by the end of the discourse (known popularly as The Sermon on the Mount) it is clear that this escape had not worked, for “when Jesus had finished saying these things, the crowds were astounded at his teaching” (7:28).

In the middle section of this long discourse, the section from which this reading comes, the Matthean Jesus instructs his listeners on righteous-justice (6:1–18). The Greek word used in the first verse is dikaiosunē, which some contemporary English translations render as “piety”. The Greek word is rich in meaning (it is a key word both for Jesus and for Paul); in the Septuagint, it often translates tzedakah, a Hebrew word used to describe the quality of God’s just and fair dealings with human beings.

The prophets, for instance, consistently advocated for righteous-justice. “Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream”, Amos declares (Amos 5:24). Isaiah laments the state of the city: “How the faithful city has become a whore! She that was full of justice, righteousness lodged in her—but now murderers” (Isa 1:21), and tells a parable ending with the despairing words that God “expected justice, but saw bloodshed; righteousness, but heard a cry!” (Isa 5:7).

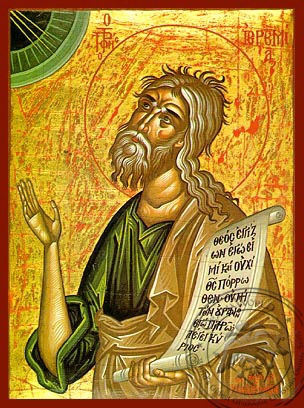

Jeremiah reiterates the instruction of the Lord, “act with justice and righteousness, and deliver from the hand of the oppressor anyone who has been robbed” (Jer 22:3) and Ezekiel warns, “the righteous turn away from their righteousness and commit iniquity, they shall die for it” (Ezek 18:26). In a vision in which Gabriel appears to Daniel, a period of seventy weeks are given for the people “to finish the transgression, to put an end to sin, to atone for iniquity, to bring in everlasting righteousness” (Dan 9:24).

In his final vision (in the last chapter of the Old Testament, in the order in which it appears in Christian scriptures), Malachi prophesies that “for those who revere my name the sun of righteousness shall rise … and you shall tread down the wicked” Mal 4:2). An emphasis on righteous-justice is also found in other prophetic works (Hos 10:12; Isa 28:17; 32:16–17; 54:14; Ezek 18:19–29; Dan 9:24; 12:3; Zeph 2:3; Mal 4:1–3; Hab 2:1–4). Righteous-justice was a key factor for the prophets. See also

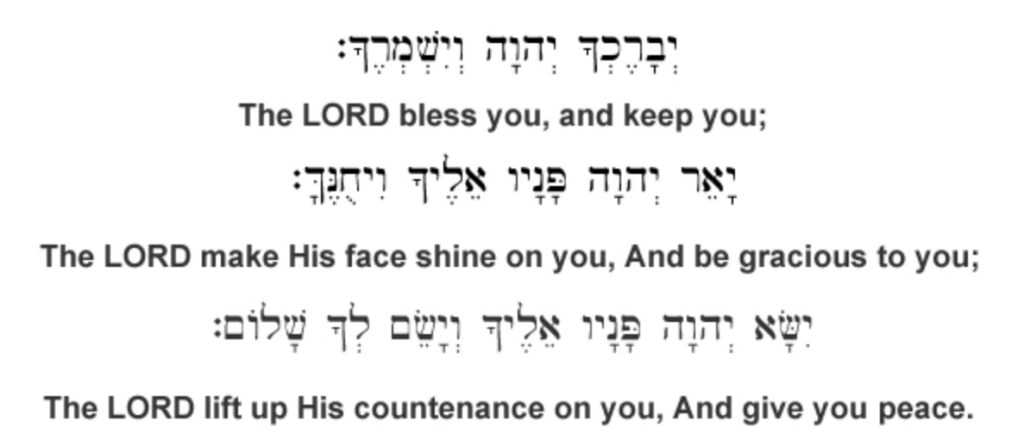

Many psalms evoke the righteous-justice of God (for instance, Ps 5:8; 7:17; 9:8; 17:15; 33:5; 50:6; 72:1–3; 89:14, 16; 103:17; 119:142; 145:7). Some psalms note that God “watches over the way of the righteous” (Ps 1:6), and “blesses the righteous” (Ps 5:12), and “upholds the righteous” (Ps 37:17). Those who practise righteous-justice “shall be kept safe forever” (Ps 37:28), they “shall inherit the land” (Ps 37:29).

Because “the salvation of the righteous is from the Lord” (Ps 37:39), the psalmist calls for celebration: “rejoice in the Lord, O you righteous, praise befits the upright” (Ps 33:1). “Surely the righteous shall give thanks to your name; the upright shall live in your presence” (Ps 140:13; likewise, 64:10; 68:3; 119:7, 62, 164). And so, the psalmist prays that the righteous-justice of God might be evident in the lives of the people: “judge me, O Lord, according to my righteousness, and according to the integrity that is in me” (Ps 7:8).

In a psalm that looks hopefully to a time when God will withdraw his wrath and bring salvation (Ps 85:1–9), we hear the words, “steadfast love and faithfulness will meet; righteousness and peace will kiss each other; faithfulness will spring up from the ground, and righteousness will look down from the sky” (Ps 85:10–11). These are the qualities of God, which the psalmist yearns to see exhibited also in the lives of the faithful: “righteousness will go before him [the Lord] and will make a path for his steps” (Ps 85:13).

“The Lord rewarded me according to my righteousness” (Ps 18:20, 24); amongst “those who fear the Lord”, “righteousness ensures forever” (112:3, 19). So, “happy are those who observe justice, who do righteousness at all times” (Ps 106:3); “let your priests be clothed with righteousness and let your faithful sing for joy” (Ps 132:9). The psalms overflow with celebrating the righteous-justice of God and calling for actions of righteous-justice to be undertaken by the people.

*****

In the context it is being used in Matt 6, this word indicates the means by which human beings might give expression to the righteousness which is inherent in God’s being. How do we live in the world in a way that shows we are committed to being the people of God? So its use here refers to how faithful followers of Jesus are to undertake just actions in their lives, not just in performing “acts of piety”. I’m going to use the translation “doing acts of righteous-justice” to convey that sense.

Jesus has already given a strong statement advocating for the importance and priority of doing acts of righteous-justice in the lives of his followers. He declares that God seeks a righteous-justice which “exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees” (5:20)—a passage which we read just a few weeks back. See

The term also appears in the teachings of Jesus in the Matthean version of two beatitudes about those who “hunger and thirst for righteousness” (5:6) and those who are “persecuted for righteousness’ sake” (5:10); the parallel beatitudes in Luke have no reference to righteous-justice. The term also appears in the well-known exhortation to “strive first for the kingdom of God and his righteousness” (6:33), and in the comment concluding the parable of the two sons, that John “came to you in the way of righteousness and you did not believe him” (21:32). (The “you” in question here must be those Jewish leaders referred to at 21:23.)

Here, in these instructions, the emphasis that Jesus brings is to reinforce that such deeds of righteous-justice are to be undertaken without any expectation of reward or admiration. “Beware of practicing your piety before others in order to be seen by them; for then you have no reward from your Father in heaven” (6:1); and then, “when you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your alms may be done in secret” (6:3–4).

This followed by “whenever you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret” (6:6), and finally “when you fast, put oil on your head and wash your face, so that your fasting may be seen not by others but by your Father who is in secret” (6:17–18). These deeds have value in and of themselves, for they show a person’s inner commitment to the way that Jesus teaches. There is no need of external acknowledgement or reward, for in each case, “your Father who sees in secret will reward you” (6:4, 6, 18).

By focussing on alms (6:2–4), prayer, (6:5–15), and fasting (6:16–18), Jesus does no less than instruct on three forms of traditional Jewish righteous-justice. Texts from the hellenistic period indicate the importance of these actions. Tobit 12:8 states, “Prayer with fasting is good, but better than both is almsgiving with righteousness”. Jesus, as always in Matthew’s book of origins, maintains steadfast and intense commitment to Torah. He is a deeply faithful Jew.

In the Letter of Aristeas, also from the hellenistic period, we find the observation that “nothing has been enacted in the Scripture thoughtlessly or without due reason, but its purpose is to enable us throughout our whole life and in all our actions to practice righteousness before all people, being mindful of Almighty God … the whole system aims at righteousness and righteous relationships between human beings” (Ep. Arist. 168–169). We shall see that this scriptural basis is the case for each of the three forms of doing righteous-justice that Jesus instructs.

*****

Alms. The first expression of righteous-justice is to give alms (6:2–4). Whilst the precise terminology that we find here appears only in later, hellenistic texts, the fundamental concept involved in giving alms to the poor is very clearly expressed in the Hebrew Bible. “If there is anyone in need among you”, the Deuteronomist has Moses declare, “do not be hard-hearted or tight-fisted toward your needy neighbour; you should rather open your hand, willingly lending enough to meet the need, whatever it may be” (Deut 15:7–8; likewise, 24:14–15). The law of gleaning made secure provision for feeding the poor of the land (Lev 19:10; 23:22; Deut 24:21; and see Ruth 2 and the later rabbinic discussion in tractate Pe’ah of the Mishnah).

The psalmist affirms, “it is well with those who deal generously and lend, who conduct their affairs with justice; for the righteous will never be moved; they will be remembered forever” (Ps 112:5–6), whilst the sage declares in a proverb, “whoever is kind to the poor lends to the Lord, and will be repaid in full” (Prov 19:17).

And Job declares his commitment to giving alms, helping to poor, when he says, albeit with a rhetorically exaggerated style, “if I have withheld anything that the poor desired, or have caused the eyes of the widow to fail, or have eaten my morsel alone, and the orphan has not eaten from it … if I have seen anyone perish for lack of clothing, or a poor person without covering, whose loins have not blessed me … then let my shoulder blade fall from my shoulder, and let my arm be broken from its socket” (Job 31:16–22).

Prayer. The second way that righteous-justice can be expressed is prayer (6:5–15). This section is perhaps best known because, whilst instructing his disciples how to pray, the Matthean Jesus offers a distinctive formula for prayer (6:9–13). Although this prayer has become known as the distinctive Christian prayer, a close study of Hebrew Scriptures shows that the concept in each clause (and in almost every case, the precise terminology of each clause) has originated in Jewish thought.

Prayer, of course, was a regular and central practice amongst the Israelites over the centuries. One tractate of the Mishnah, Berakhot (meaning “blessing”) was devoted to instructions for prayer. Hebrew Scripture contains many instances of prayers offered by key figures in Israel. In the wilderness, people ask Moses to pray to the Lord (Num 21:7). When her son in born, Hannah prays with praise and thanksgiving (1 Sam 2:1–10), and then at Mizpah, her son Samuel (now an adult) prays to God on behalf of the people (1 Sam 7:5), and the people ask him to pray to God on their behalf (1 Sam 12:19, 23).

David finds “courage to pray [a] prayer” to God after having been chosen “to build a house” for God (2 Sam 7:27; 1 Chron 17:16–27), and then when the Temple had been built, Solomon prays a long, extended prayer to dedicate the building (1 Kings 8:22–53). Prayer is integral to the life of the people of Israel. At the end of the Exile, Nehemiah fasts and prays for the people (Neh 1:4–11). The prophet Daniel prayed three times a day whilst he was in Babylon, despite orders to the contrary (Dan 6:10–13)—a practice that appears to have been kept by Peter (Acts 3:1; 10:3, 30).

The section on prayer is omitted from the lectionary selection for Ash Wednesday. (Neither does it appear anywhere else in the Revised Common Lectionary.) Why might this be? Perhaps to ensure the focus on this day of penitence stays on almsgiving and fasting—actions which require specific external activity, not simply the internal activity of prayer?

Fasting. The third way of acting with righteous-justice that Jesus teaches is fasting (6:16–21). A fast was a way to signal fidelity to the covenant with God, in the face of personal distress (2 Sam 12:22–23) or when the nation was under attack (2 Chron 20:1–4). Jezebel called for fasting in her scheming to obtain the vineyard of Naboth (1 Ki 21:9–12) and Ezra decreed a fast whilst still in exile, prior to returning to the land (Ezra 8:21–23).

In exile, Queen Esther ordered fasting, which Mordecai carried out (Esther 4:15–17); before he is sent into exile, Jeremiah reported that King Jehoiakim proclaimed a fast for “all the people in Jerusalem and all the people who came from the towns of Judah to Jerusalem” as preparation for hearing the scroll read by Baruch (Jer 36:9–10).

When the people of Nineveh repented in response to the preaching of Jonah, they held a fast (Jonah 3:1–5), while the prophet Joel calls the priests to put on sackcloth and “sanctify a fast” (Joel 1:13–14) and then for all the people to “sanctify a fast” (Joel 2:15–16). These fasts were intended to recall the people to the covenant that they had with the Lord God, and lead them to focus on his they might best live in accordance with lives of righteous-justice that were expected from that covenant.

The call which we hear on Ash Wednesday in the Gospel that is offered (Matt 6:1–6, 16–21) is thus a call that Jesus draws from deep within the wells of his Jewish faith and tradition: a call to be intentional, focussed, and committed in acting in ways that demonstrate the righteous-justice of God, lived out in the lives of faithful believers, especially care for the needy and focussing on our relationship with God. It is a call that sounds with clarity for us at the start of this Lenten season.

*****

See also